10 ways to have happy playtesters

Sharing what I learned about creating the best playtesting experience at a recent Harrisburg University public playtesting event. Getting inspired by student designers!

Last week we looked at a game where every choice is painful but in a good way. It’s an exploration of the difference between “feel good” games and “feel bad” games. Plus some great thoughts and discussion in the comments.

This week we are thinking about playtesting. It’s a topic I covered before with questions to avoid when showing your game to others. This time, however, I want to share some thoughts on how to keep your playesters happy — general advice for any type of testing.

Practicing for PAXU at HU

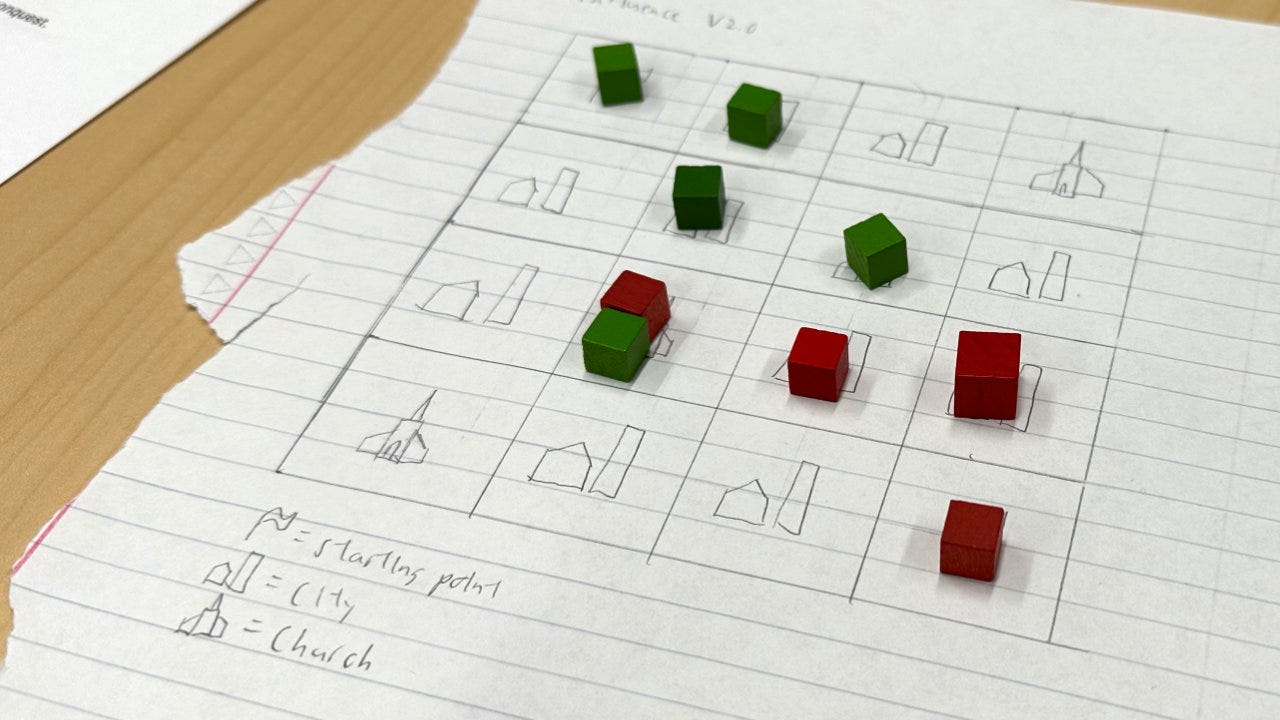

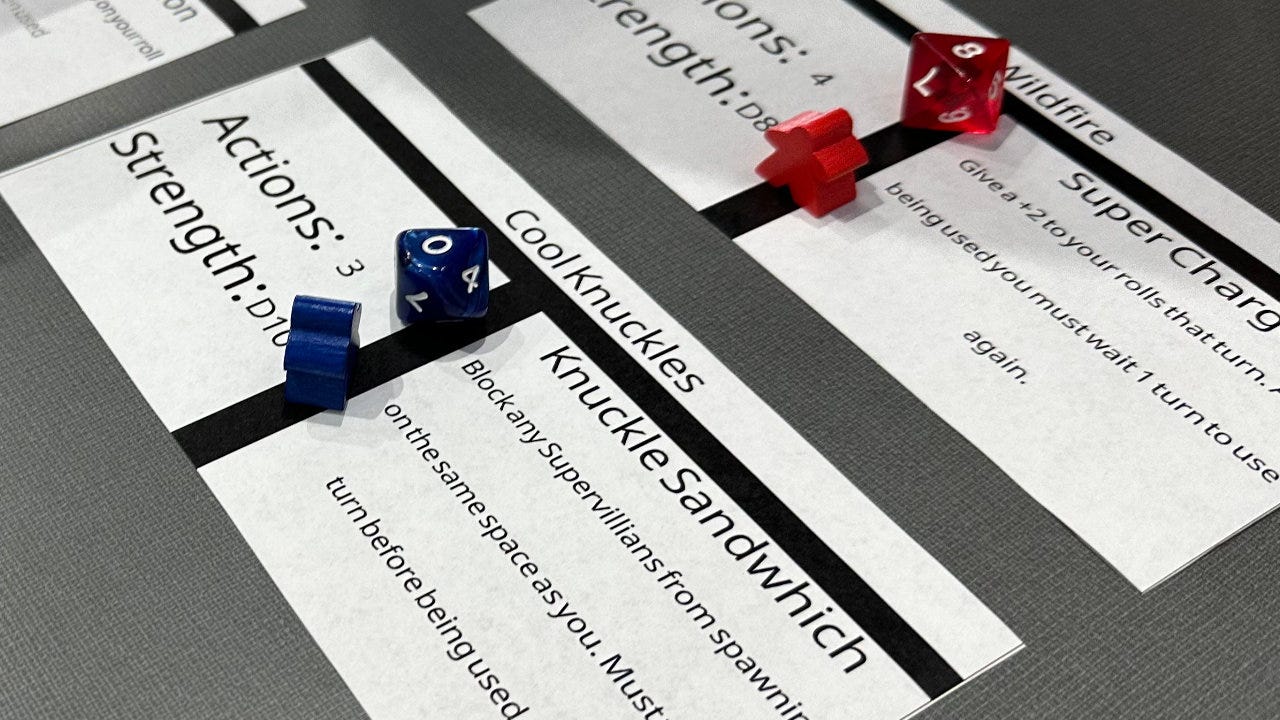

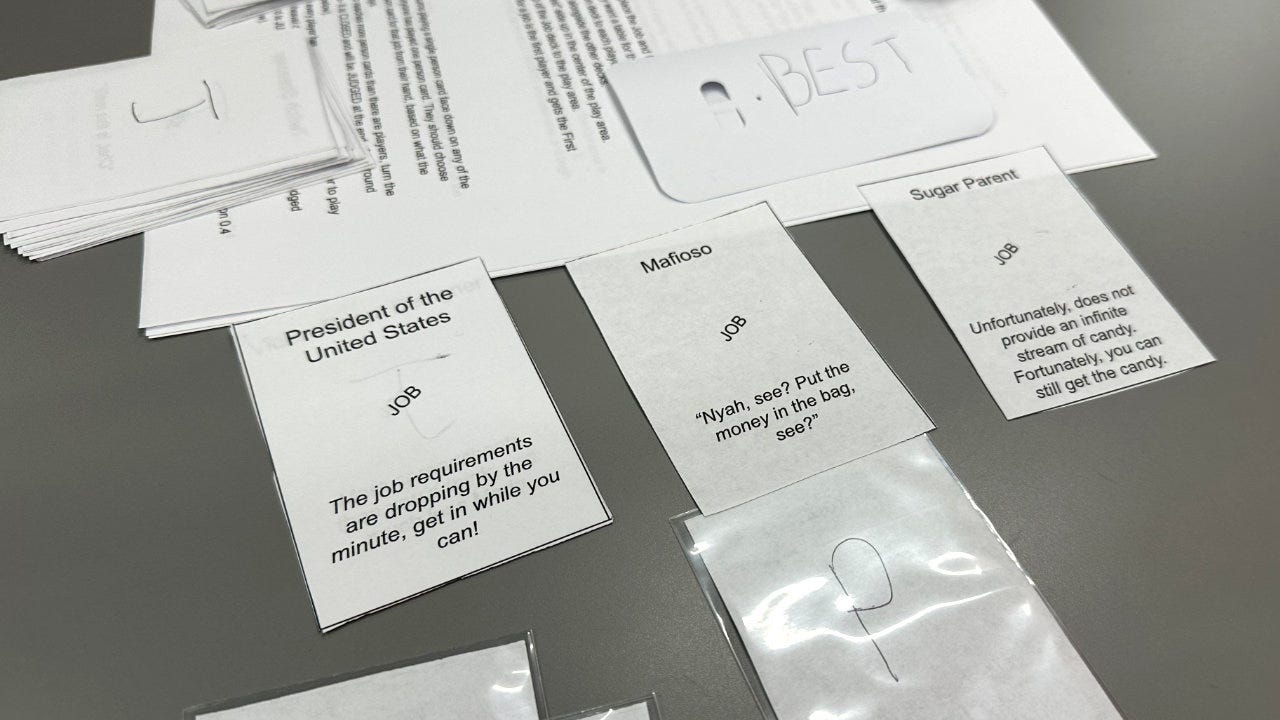

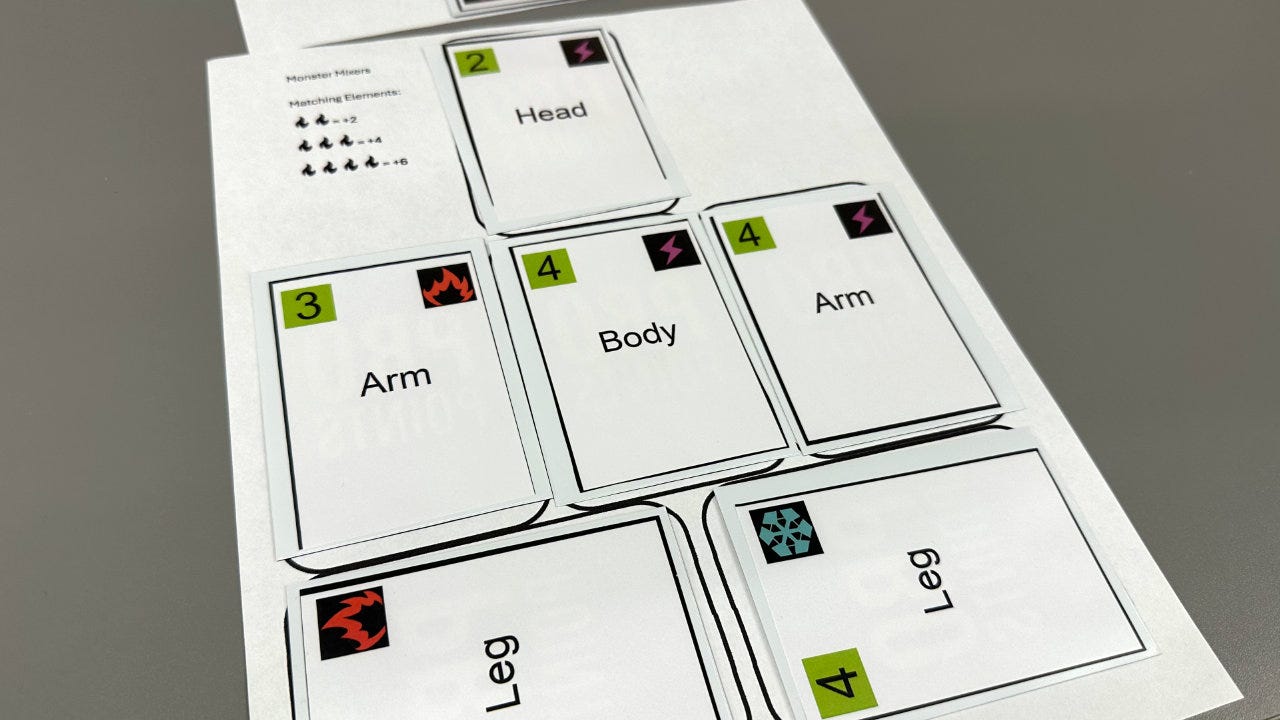

I had the opportunity to participate in a public playtest of student-designed games at Harrisburg University last week. The students are part of the “IMED 315 - Tabletop Game Design Studio” course co-taught by professors Greg Loring-Albright and Anthony Ortega.1

The students will be showing their games at PAX Unplugged (PAXU) in November as part of the Unpub at PAXU event that takes place there.2

The public playtest at Harrisburg University included both students and people from the community (like me). The goal was to help the students improve their games and playtesting processes in advance of PAXU, and it seemed like a huge success.

There were about 10 student games on display, a lot of other students around to play them, and it was all facilitated by Greg and Anthony.

Making a checklist for myself

I was particularly interested in attending the playtesting because I plan to demo a design at the upcoming Unpub Festival in Baltimore next year. It’ll be my first time doing a public demo at a large event, and I’m trying to collect as much information as possible ahead of time. At last year’s Unpub, I learned how to pitch a game and what questions to ask when playtesting. At the Harrisburg University event, I wanted to really think how to provide the best experience for playtesters.

The time went by quickly, so I was only able to play five of the roughly ten games being tested by students. One game I was able to play twice. For each one, I made notes about the game, but also what they did well in creating a good playtester experience.

I came away from the event extremely impressed with the students, their designs, and the program.

It was a great day, but why? How did they create a good experience?

10 ways to have happy playtesters

1. Tell me how long it will take.

The Harrisburg University event ran from 11:15 - 2:15 PM. Removing time for initial instructions/logistics and then for a quick wrap-up, there wasn’t an excess of time left. I had to choose games carefully, knowing that they won’t all get played. This is always the case with events like Unpub, Break My Game, and other mass playtesting events. Too many games and too little time.

So before starting the playtest, let everyone know how long the game will take. Is this a quick 10 minute game or a deep 30-50 minute game? Are we just playing a single round to check the mechanisms, or do you intend to play out the entire game? Are players able to leave early, or would that break the test?

Giving information about duration and expectations allows playtesters to plan their time carefully and make the most of the day.

2. Tell me if this is a blind test or not.

Many times, playtesting is what’s called guided playtesting. This means the designer or someone familiar with the game teaches testers how to play and ensures they are following the rules. The other type of testing is unguided or blind playtesting, in which the players are handed a rulebook and they need to figure it out on their own.

Both types of testing are essential to good design, but not all playtesters are as willing or comfortable with both. Sitting down with a group of strangers and trying to learn how to play a game from a rough draft rulebook isn’t for everyone. Blind playtests also require more time because some of the time is spent just learning the rules.

If possible, make the type of test (guided or unguided) as clear and upfront as possible. This prevents people who don’t want to be part of a blind test from sitting down and getting hooked into something they’d rather not do. Or perhaps allows people looking for rulebook testing experience to jump in!

Let people know up front and give them the information to decide.

3. Give me the pitch.

I just sat down at the table. You, as the designer, know everything about the game — it’s history, it’s theme, how it is all put together. I know absolutely nothing.

Giving a concise pitch that includes the following immediately conveys what I need to know:

Game name

One sentence pitch (10 word max)

Number of players (kids? adults?)

Playtime / duration

Touchstones / inspirations

Who is this game for?

Narrative / theme (“You are a…”)

While it’s the mechanisms that are often being tested, the theme is just as important in learning the game. Sarah Shipp notes this in Thematic Integration in Board Game Design (Shipp, 2024):

“Theme is often described as the “why” of a game. Themes help with rules comprehension by giving reasons for the mechanics. Themes can help set players’ expectations for what kind of experiences or emotions the game provides. Themes can also help to create the experience and provide atmosphere to the gameplay.”

Once we’ve all heard the pitch, we can more easily learn the game and understand the mechanisms. We know what player promises the game makes. We know where player agency or randomness might come into play. Then we can all get started on the teach and have a good playtest.

4. Be ready for when the game breaks.

In one of the games I played, a strategy or method arose that was pretty game breaking. It was an edge case, but one that effectively knocked a player out of winning for the rest of the game. In another game, some rare ties created a weird game state. In a third game, it turned out it was possible to unexpectedly run out of cards.

This stuff happens during playtesting. In fact, I’d argue it’s exactly why we do extensive playtesting of games. Finding game breaking strategies and weird edge cases isn’t a flaw — it means the testing works!

That said, it can come as a surprise and create an awkward situation. Designers need to be ready to roll with it, change or adapt rules on the fly, and just keep going. Take some notes, make sure everyone is still content and get the test to the end.

I was impressed with how well the students handled moments like this, and I can only hope I can perform the same when I test my games in the future.

5. Call it if the game goes too long.

Some games have a strong game arc, meaning that the beginning, middle, and end of the game are very different from each other. The only way to effectively test the game is to play all the way through from beginning to end. Other games, however, have less of an arc and are largely the same throughout.

It’s OK to call the test short if the play is repetitive and there are diminishing returns in the information being gathered. There may be little reason to play out the entire game.

Let players know ahead of time if you need to see the entire game or just a few rounds. Either is fine. It just depends on your goals.

6. Be familiar with games similar to yours.

It is hard, if not impossible, to have a truly unique game that isn’t similar to any of the other 29,280 games listed on BGG. If you have an idea for a game, chances are someone else has already designed a game with similar mechanisms and/or theme. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t make your game. Indeed, make it! But do some searching for similar games. Get familiar with them. And understand how and why your game is different.

Often, a design can benefit from playing or at least reading the rulebooks of similar games. As a playtester, it’s good to know that the designer has done their due diligence and become familiar with similar games. It allows us to speak about common games and makes feedback that much easier.

7. Proxy cards so I can shuffle them.

This is an easy one. If you hand me a deck of protoype cards, it’s totally fine if they are just sheets of paper in sleeves. But if I need to shuffle them, please put some old Magic: The Gathering or Pokémon cards in behind the prototypes. Land or energy cards are all but free and add the required stiffness so they can be shuffled.

This is especially important in deck-building or other games that require frequent shuffling.

8. Give me something interesting to do.

Playtesting is intended to find flaws in games, to highlight the best parts, and to provide feedback that can be used to advance the iterative design process. Games don’t need to be perfect during playtesting, but they should give players something interesting to do each turn.

Ahead of playtesting, consider the following:

Is there enough player agency to ensure choices matter?

How large is the game’s decision space?

Can players plan their turns while waiting during downtime?

Have all Hobson’s Choices been identified and eliminated?

Those questions can largely be answered before playtesting ever begins, and certainly before public playtesting.

Always be on the lookout for false choices which only provide the illusion of choice.3

9. Make it large, legible, and easy to read.

Not everyone has the same vision abilities. Take it easy on your testers and make text on cards, boards, and other components large and easy to read. It’s OK to have handwritten bits, but as someone with rather poor handwriting, get some assistance from someone who can write clearly.

Card designs are rarely final or even have layout during playtesting, but use a highly legible font that can be read at a distance. It’ll speed up testing, reduce having to pass components around, and generally make everyone a lot happier.

10. Ask me some questions!

At the end of the playtest, you have a table of multiple people who took the time to play your game. They are the most valuable design resource you have, and you only have access to them for a few short minutes. What do you do?

I understand that getting electronic feedback is easier and makes data collection less of a burden, but it’s also impersonal. No one wants to write all of their thoughts into a little Google Form on their phone while there are other games to be played.

Ask me questions about what it was like to play the game! It’s the best way to show both interest and appreciation for the people who tested your game. It’s the best way to get feedback with full context and background. Resist the urge to sit there and just show me a QR code.

Preparing for Unpub in Baltimore

As I prepare to demo a game at Unpub in March 2026, the above tips are some of the ones I need to keep in mind. It’s a lot to keep track of! I also need to think about how to pitch my game, the right playtesting questions to ask (and not ask), what prototype components to use, and a thousand other things.

I can’t be the only one, right?

So I’ll probably try to compile all of this into some sort of document and share it with you in the lead up to Unpub. I’m not sure of the format, but I’d like to include things like the “fill in the blank” pitch form I’ve used in public library classes.

Let me know in the poll below what you’d want to see the most.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Student game designers are inspiring: I was really impressed with not only the game designs of the students, but also their professionalism. They took the event seriously and created a fun day for everyone. Seeing young people who love games, love game design, and want to share it with others… is just immensely inspiring and energizing!

Give your playtesters a good experience: By following a few simple tips, it’s possible to create a great experience for the people taking the time to play your game. Simple things like communicating duration and giving a quick pitch go a long way. None of the above tips are too complicated.

Prepare the experience, not just your game: The goal of a playtest is to test and improve a game’s design. Certainly prepare your game, but human playtesters are a critical part of that process. It’s worth thinking about what the experience will be like for them, and how you can make it as enjoyable as possible. Plan ahead for how you will improve the overall experience for everyone.

What would you want to see in a Skeleton Code Machine Guide about taking your game to Unpub or Break My Game? What else should I look into before running my first public playtest event in March?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Tumulus 04. “Return to the sea.” is shipping now! Start your four-issue subscription and get design inspiration delivered to your door each quarter.

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

If you play board games, you probably have heard of Ahoy published by Leder games in 2022. That was designed by Greg Loring-Albright, one of the professors and facilitators of the playtesting event at Harrisburg University.

The Unpub area at PAXU is always one of my favorites. You need to check it out if you are attending PAXU this year or in the future. You just show up, find a table looking for players, and hop into a prototype game. Even the most broken games can be a great source of creative inspiration.

A false choice can arise in at least three different ways: (1) The player has no information or knowledge by which to make the decision. All options seem equally good or bad, and a random selection is as good as any. (2) The choices all lead to the same outcome, regardless of the option selected. (3) The output randomness built into the system greatly outweighs the impact of any actual player decisions based on available options.

May I suggest a number 11 for the list? "Remember to thank those who gave their time to help with the playtesting" 😊

I wanted to vote for both playtesting and pitching!