Every choice in this game is painful

Exploring a "subversion of the point salad paradigm" game that makes every decision seem like a bad one. How The Field of the Cloth of Gold creates it's own kind of fun out of gift giving.

The last two weeks, we explored different dice mechanisms including the roll three, pick two of Rumble Nation and the discard, re-roll of Mythic Battles: Pantheon.

This week we are switching it up and looking at a game with no dice — The Field of the Cloth of Gold by Amabel Holland. The only luck in the game comes in the form of random tile pulls. The interesting part, however, isn’t the tiles… it’s how it makes every action help your opponent.

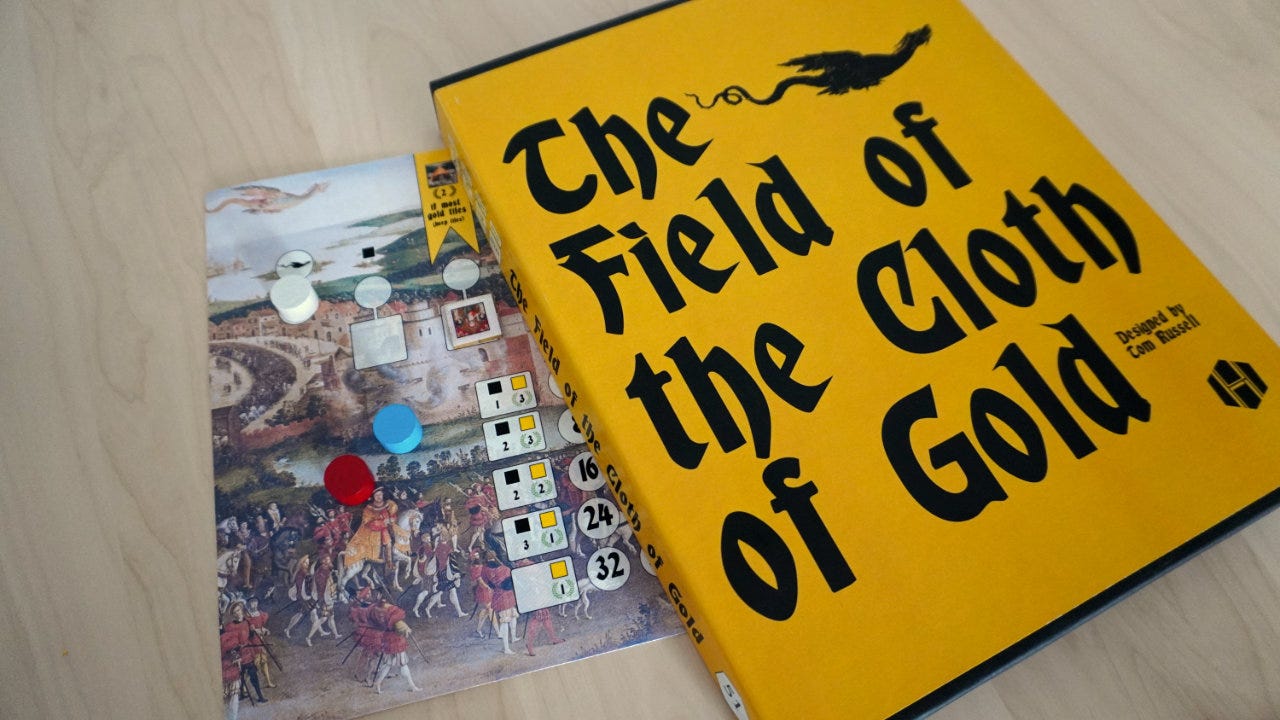

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

In June 1520, King Henry VIII of England and King Francis I of France met at Balinghem in northern France. Ostensibly to improve relations between the two kingdoms and reduce the likelihood of war. While the event was planned in detail by Cardinal Wolsey to ensure both sides would be equal, each tried to outdo the other with extravagant gifts and displays. It became known as The Field of the Cloth of Gold after the silk-gold cloth extensively used for tents and banners.

This, excluding the “monkeys covered with gold leaf” mentioned in some sources, is the setting of The Field of the Cloth of Gold (Holland, 2020) from Hollandspiele Games:

In this game, two players briefly assume the roles of these divine majesties. If you are afeared of the weight of the crown, and all its worries, fear not: this amusement only requires you revel in the greatness of your kingdom, not to rule it.

Mechanically, the game is fairly straightforward:

Select a space: Players alternate taking turns by moving one of their two cylinders to a new, empty space on the board.

Gift the tile: Take the tile next to the space they just moved to and give it to their opponent as a gift.1

Resolve the action: Perform the specific action for the space that was selected.

The available action spaces range from taking new (face-down) tiles, comparing the number of gold tiles for points, scoring points for sets of tiles, or “compete in displays of manly violence” using red tiles. Sometimes the tiles are kept in your hand or court, and other times they are all discarded.

There is also a dragon space that, when selected, allows the player to move a white dragon piece to any open space on the board. This effectively blocks that space until the dragon is moved again.

If the last tile is drawn from the supply or either player achieves 30 points, the game ends.

The agony of gift giving

The core game loop continues throughout the game: select a space, gift a tile to your opponent, and resolve the selected action. Some tiles accumulate secretly in your hand, and others are visible in your court.

It seems almost too simple. Is there actually a game there?

Playing the game, you quickly realize that the strategy isn’t so much about just grabbing tiles and scoring points — it’s about denying points to your opponent. But that is incredibly difficult, because with each move you are gifting them more tiles.

Perhaps you’d like to take the Gold action — compare gold tiles, whoever has more gets 2 victory points (VP), and keeps their tiles. Doing so, however, might mean you must gift a green jewel tile to your opponent, each of which is worth N^2 points at the end of the game.2

More than that, as you move your cylinders to new locations, that both blocks and opens a new space. You can move from the Blue action to the White to claim a few points, but this not only gifts yet another tile to your opponent but now allows them to take the Blue action to score more points.

Every move helps your opponent, albeit to varying degrees. It’s gift after gift to them, always opening up more opportunities for them to score.

The 2020 review from Demetri at Pixeldie perhaps sums it up the best:

There is no action in this game that doesn’t advance your opponent’s position, often significantly, and that is the true crux of the game. Imagine if 90’s leather jacket Knizia put two knives in a box and said “you’re only allowed to use these on yourselves, now win”.

It’s frustrating, exhausting, and when played with the right people, incredibly mean.

So why would we play a game that feels bad?

Subversion of the point salad paradigm

Sometime in the 2010s, a style of euro-game emerged that allowed players to score points in all sorts of ways — a wide variety of unrelated sources. Almost every action scored at least some form of points. This meant that there was rarely a single, dominant strategy that could be used. These games became known as point salad games, drawing analogies from buffets and salad bars. Players pick and choose where to get points without the need to dedicate effort to a single strategy.

Examples of point salad games include Agricola (Rosenberg, 2007), The Castles of Burgundy (Feld, 2011), and the self-referential Point Salad (Johnson, Melvin, et al., 2019).3 The latter of which claims “over 100 ways to score points” as one of its defining features.

The publisher description of The Field of the Cloth of Gold mentions this:

A sort of subversion of the point salad paradigm, The Field of the Cloth of Gold harkens back to the feel of the classic German games of the 1990s: simple, elegant, austere, and politely vicious.

In point salad games, players are always getting points from many different sources. They are often “feel good” games where even suboptimal actions that will ultimately lose the game still yield points. All is well until you add everything up at the end and see who won.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold inverts this paradigm and becomes a “feel bad” game. Every action hands points and advantage to your opponent. Even optimal actions that may win the game can be tough and painful choices.

It is this challenge and struggle with each action that creates a different kind of fun for players. The simple rules create tough choices and the need to think about your opponent with every move — trying to guess that they want, and gifting them whatever they least desire.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Point salad games: There is much debate over what point salad games are and if the term is derogatory or not.4 That said, it’s an extremely popular design style and one that can be appealing to newer players. It doesn’t feel as punishing as other types of games because everything you do is rewarded with at least a few points. It’s hard to end up with zero at the end of the game.

Subverting conventions: While I’m not sure if The Field of the Cloth of Gold was designed from the start as “a sort of subversion of the point salad paradigm” or not, it does so with great skill. As a designer, having a deep knowledge of different styles and types of games allows for this type of inversion, often creating something unique, new, and interesting.5

Feels good to feel bad: Just as there are great movies that make the audience feel bad, the same can be said for games. Some games create a decision space so tight and decisions so tough that it can be agonizing — and that creates a very special kind of fun that appeals to many people. Simple rules and extremely tough decisions are a formula that has worked well for Dr. Knizia.

What do you think? Which games have you played that are filled with agonizingly tough decisions? Have you played any other games where it feels like almost every action is bad for your side?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Are you participating in MÖRKTOBER this year? Grab the creator kit and make something for each of the prompts. It’s chill, not a challenge. Make stuff daily or on your own schedule. It’s never too late to begin. 🎃🎃🎃

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

While I appreciate the thematic element of the player taking the tile and then giving it to their rival, in practice this just means that your opponent takes the tile from the space you selected. When I played, we didn’t actually take and then hand over the tiles.

Green jewel tiles are scored at the end of the game. Their value is based on the number of green tiles you have. One tile is 1 VP, two tiles are 4 VP, three tiles are 9 VP (3+3+3), and four tiles would be 16 VP (4+4+4+4). When you need just 30 VP to instantly end the game, this can be a significant amount of points!

Is Agricola a point salad game? I don’t know. It does have many, many ways to score point. It also allows you to go fully negative with your score when you let your family starve. I included it here when doing initial research on point salad games because it is frequently cited as one on BGG. Like anything, strict definitions can be messy.

I have very little interest in pedantic debates over what is or is not a point salad game. And even less interest in deciding if they are fun or not.

Hollandspiele games are well-known for subverting genre expectations and creating interesting games. Endurance (which I have played) and Meltwater (which I have not) are two good examples of this.

I had not heard of this game, thanks for the review. Although it strikes me a bit odd to call Agricola a point salad game. It's very easy to have a starving family if you're not careful.

This is a killer title, and one of the best things I've read all week (and i read quality!)