What is a game's decision space?

Exploring increasing and decreasing decision spaces in tabletop games, and how they can be manipulated to create the best player experience.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on decision spaces in tabletop games. Be sure to check out Part 2 - I’ll give you a choice: take it or leave it on Hobson’s choices.

Last week we looked at open vs. hidden information in The Tea Dragon Society Card Game. We also learned that most readers (41%) would choose Rooibos as their tea dragon and poor Chamomile was the least popular (13%).

Also, I’m happy to announce that Tumulus Issue 3 is arriving at subscriber’s doors. Love seeing people sharing it on social media like Play Solo and Big Puffin Games!

This week we are exploring the concept of decision spaces in tabletop games — what are they and why they matter.

What is a decision space?

In tabletop game design, the decision space of a game is a measure of all of the meaningful choices available to a player at a given time — choices that allow a player to have agency.

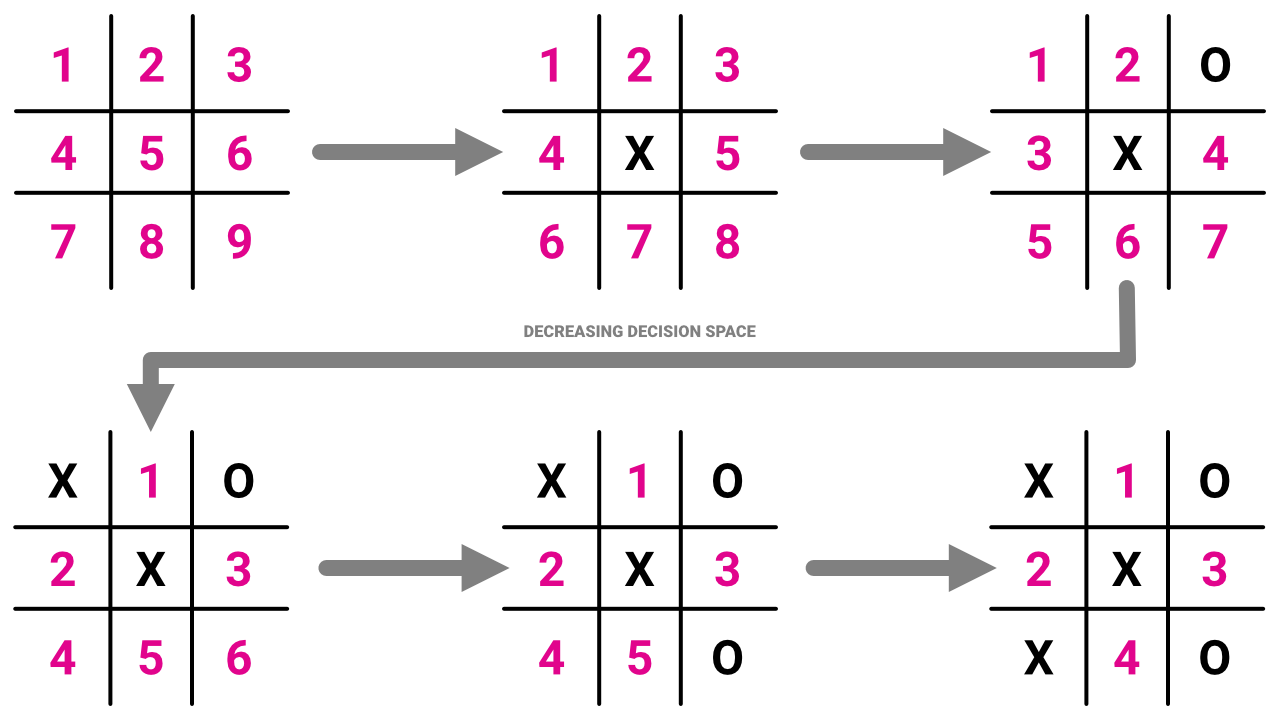

Let’s look at a very simple example using the game tic-tac-toe.1 At the start of the game, the first player has nine spaces to choose from when placing their mark.

In strict terms, that’s the decision space (i.e. 9 possible options). The play area is, however, perfectly symmetrical. This means that placing in a corner is equivalent to any other corner. It doesn’t matter which corner they might choose because they are all the same when the other player takes their first turn. The same could be said for the side spots as well. So in practice, the effective decision space is smaller than 9.

We can look at decision spaces in other games in the same way: How many truly different options and choices are presented to the player on their turn?

Chess has a relatively simple ruleset, but the decision space is much larger. Each piece has limited movement capability, but the player can choose almost any piece to move and each piece has multiple paths.2

In many deck-building card games, the player has a hand of about five cards. This creates a limited decision space (i.e. 5 cards), but some expand this by allowing the cards to be played into different lanes. For example, Compile (Yang, 2024) uses 5-card hands with three lanes but then limits which cards can be played into each lane.

Many heavy euro-style board games have huge decision spaces created by many pieces, currencies, action spaces, and interactions with other players. Games like Kanban EV and others by Vital Lacerda are famous for this complexity.

Wargames with a grand strategic scale and potentially hundreds of counters on a hex map increase this space even more.

Option 1: Fewer choices over time

The decision space of a game is rarely static and unchanging. Even in the example of tic-tac-toe, each player has fewer choices each turn. The final turn of the game is completely free of player agency as there is only a single place to go. There is no choice at all.

This is an example of what I’d call a decreasing decision space in a game. The game begins with a wide array of options for the player, but they gradually shrink over the course of the game. This might be due to having fewer cards in their hand, fewer action spaces available on the board, or more restrictive conditions.

Two examples of this come to mind:

Gloomhaven combat: At the start of combat, Gloomhaven (Childres, 2017) players have quite a few multiuse cards. As those are played and the character becomes more fatigued, the choices become more limited. By the end of combat, they might only have one or two cards that can be played (or make sense to play).3

Trick-taking games: In many trick-taking and card-shedding games, the number of cards in the player’s hand decreases. This naturally reduces the decision space as the round progresses. When combined with the rule that you must play a matching suit if you have one, the decision space can suddenly decrease.

This sort of decreasing decision space shows up in games that might be described as “puzzly” by some. It has a feel similar to working on a crossword puzzle, sudoku, or jigsaw puzzle. The challenge and fun is getting those last pieces to fit in an ever decreasing decision space. That gradual constriction is a kind of fun many enjoy.

Option 2: More choices over time

In the opposite case, some games present the player with more choices and options over time. I’d call this an increasing decision space, and it’s the type of game I personally prefer.

In games with an increasing decision space, the first turns are constrained. The player is presented with just a few options. Then, gradually over the course of the game, the field opens up with more and more options. This may be done by gaining new abilities, unlocking new worker spaces, gaining more action points, or building more units. By the end of the game, the decision space is very large.

Games like Carnegie (Georges, 2022) and Troyes (Dujardin, Georges, et al., 2010) are good examples of this type of decision space expansion. Throughout the game, players can acquire new actions (e.g. departments or activity cards) which allow more complex actions. It’s the selection of which powers and abilities to choose and how to trigger combos that many players (myself included) enjoy.

Dynamic decision spaces

As with mechs, it’s difficult to create strict definitions for decision spaces that remain useful. It is rare that a game has a strictly increasing or decreasing decision space. There are far more than just two options.

Consider Compile as mentioned above. Players draw five cards and then play them out one at a time — decreasing the decision space. One of the actions in the game is to refresh your hand up to five cards — increasing the decision space. This creates a fascinating choice in itself. Do you maintain your tempo and keep playing cards until your hand is empty and then refresh? Or do you refresh a little early, breaking your tempo but setting yourself up for future turns?

Gloomhaven, which I used as an example of decreasing decision space for how it handles combat, could be considered an example of increasing decision space at a strategic level. Players unlock more cards, more locations, and more characters throughout the game. It’s only at the tactical level do players quickly exhaust cards.

The aptly named Decision Space podcast had an episode about this where they divided the types into waning (decreasing), waxing (increasing), static (no change), and dynamic (increasing and decreasing). Although I’d argue that it’s hard to find a game with a truly static decision space, I appreciate the terms.

Ways to manipulate decision spaces

Now that we understand what a decision space is and how it can change, how do we use this in tabletop game design? Manipulating the decision space can have significant impacts on the pacing, feel, and player experience of a game.

Unlock new abilities: Allow players to gain new actions throughout the game and to upgrade their actions into more powerful versions. This can be done by purchasing the actions as in Troyes, drafting cards as in Blood Rage (Lang, 2015), or gaining more currency to be able to afford new actions.

Expand the map: Games like Revive (Meissner, Svensson, et al., 2022) start with a very small explored section of the map, restricting movement. Players explore and unlock new parts of the map, increasing the movement decision space.

Make the restriction part of the game: Use action selection systems like a rondel to limit the actions a player can take, but also allow the player to have influence over the system. Perhaps they choose a different action, but it costs more. Or they can take an action to adjust the rondel.

It’s notable that most TTRPGs engage in ways to increase the decision space as a campaign progresses. As characters level up, they gain new abilities, unlock spells, and have a wider selection of equipment. The map of the explored world usually expands with new places to visit. The number of known NPCs and possible side quests increases over time. Only in combat does the decision space sometimes decrease.

The dangers of a wide decision space

While some players enjoy an ever-increasing decision space, remember that it’s not for everyone. Too many choices and some players may end up with a bad case of AP, as I discussed in This player is not playing: what can I do? last year. In fact, in that article, my top tip was to limit the decision space!

Some designers abide by the Rule of Three for decisions presented to the player — no more than three choices at any given time. Although this could be combined with turns, steps, and phases so that while the player never has more than three options at a time, the effective decision space is quite large.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Understand the decision space: Whether you prefer an increasing or decreasing decision space, it’s important to understand your game’s design. Try to identify what type it is, how dynamic it is, and how it supports the theme of the game. Your choices have a huge impact on the kinds of fun your players will have.

Increasing or decreasing: While I strongly prefer increasing decision spaces, everyone’s preferences are different. There is no right answer here. Instead just know who you are making the game for and watch out for an AP-prone design.

Make the decision space part of the game: Consider allowing the player to manipulate the decision space during the game — decide when to draw more cards or if they want to break the rules of the rondel. This potentially allows players to customize the experience to what they prefer.

What do you think? Do you prefer increasing or decreasing decision spaces? Do decreasing decision space games always feel like a puzzle to be solved?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

I’ve only recently learned that tic-tac-toe is the American English name for this game. It’s often called noughts and crosses in parts of the UK, and Xs and Os in the Canada.

I’m making a distinction between decision space in the theoretical vs. the limited decision space that would achieve victory. In chess there are many possible moves, but only a smaller subset of those would make sense in advancing the game toward victory.

It’s been quite a few years since I played Gloomhaven, so my memory might not be the best on this. I know the game has many fervent fans. Please forgive me if I’m not conveying all the nuance and complexity of combat.

Maiya's comment made me also want to share how the game of tic-tac-toe is called in my home country, Brazil. We call it "jogo da velha", which, in a translation from Portuguese, means something like "the game of the old woman/lady".

Certainly fascinating to think about :)! Thank you for sharing.

I think, for me, it probably depends on what I'm after in a game... and what type of game it is. Waxing can be really a nice way to gradually learn the mechanics of something, and new things always seem more "shiny"... though there might be a point where it's too much – although that probably also depends on the pacing of the increases.

Dynamic can be quite nice, it gives more a sense of control.

I can see a waning space potentially being super atmospheric if used in the right context, like, in a game about surviving a long winter, or something like that?

That said, even static can be great, if the options are great and/or many from the start! Or, the space can stay the same size, but the options swapped out – I'm currently reading "Under Hollow Hills" by the Bakers, and you always have the same number of "plays" (moves, options), even the same ones, but other things in the game changes – most notably your appearance/imagery, through stepping toward summer/winter, and your bonuses to your plays also change around. An interesting contrast to most other broadly PbtA games, where you often can gain more moves over time. I also just read "Wanderhome" by Jay Dragon, a Belonging Outside Belonging game; and there (mostly) the number of things marked on your sheet stays the same, but they can evolve/change over time, getting swapped out as your character changes. And I guess, all the while, the "some things you can do" list stays the same – unless you swap playbooks, which you do have the option for on an advancement (either by your character retiring and you making a new one, or them changing so much they need a new playbook). And I suppose, the things you can do are essentially endless, moves/plays/things you can do are just some, not all, the options.

(Also, as a fun aside, we call tic-tac-toe "luffarschack" over here in Sweden – which means something like, "tramp/vagrant('s) chess" ^^)