When is randomness OK in games?

I lost a game of Kingmaker when plague struck Calais and I've been thinking about it ever since. Exploring thematic vs. abstract and random vs. low-luck games and the idea of zero-luck TTRPGs.

Last week we chatted with Steph from TTRPGkids about choose your own adventure games, playing TTRPGs with kids, and how to design non-violent obstacles in games.

This week I’ve been thinking about randomness in games — when it is acceptable and when it ruins the player experience. It’s complicated!

Kingmaker

I had the wonderful opportunity to play the original Kingmaker (McNeil, 1974) recently, and haven’t stopped thinking about it since. To understand why, we’ll need to go over a little about how the game works.1

Kingmaker is an Avalon Hill wargame that simulates the 15th century War of the Roses and associated civil wars in England. Players represent warring factions using the houses of Lancaster and York as pawns, vying for control of a single heir to be crowned king. Players recruit nobles, muster armies, battle, and attempt to capture the last living heir. Nobles command your armies and have a name (e.g. Courtenay), usually a title (Earl of Devonshire), and sometimes an optional station (e.g. Marshal of England).

The rulebook isn’t overly long, but dense — filled with exceptions, notes, and fiddly little quirks.2 Everything you’d expect in an Avalon Hill wargame from the 1970s.

The King is called to Rye

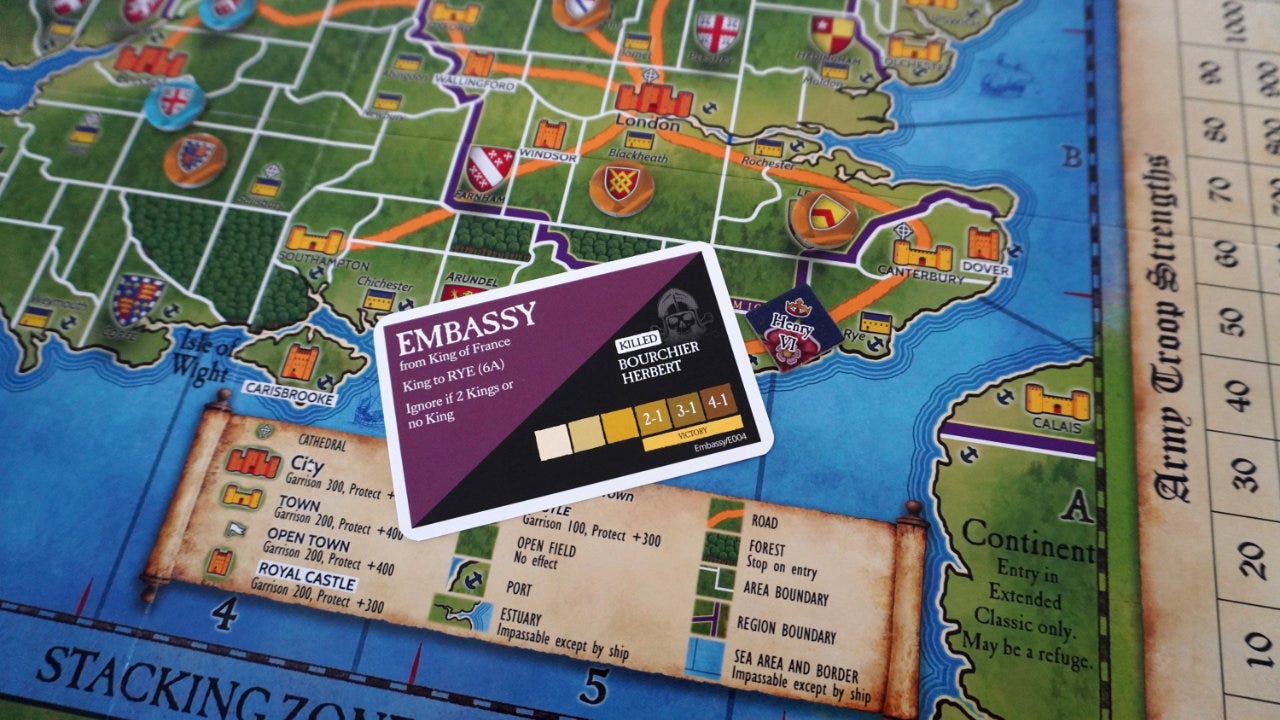

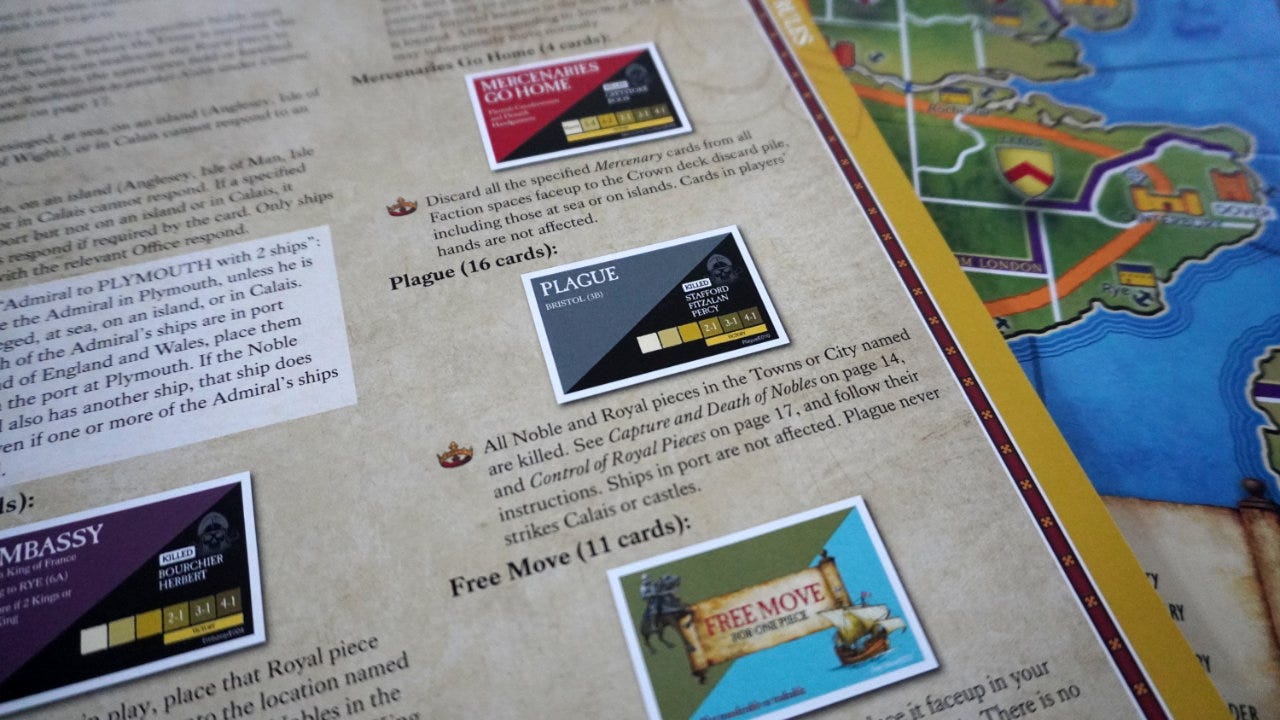

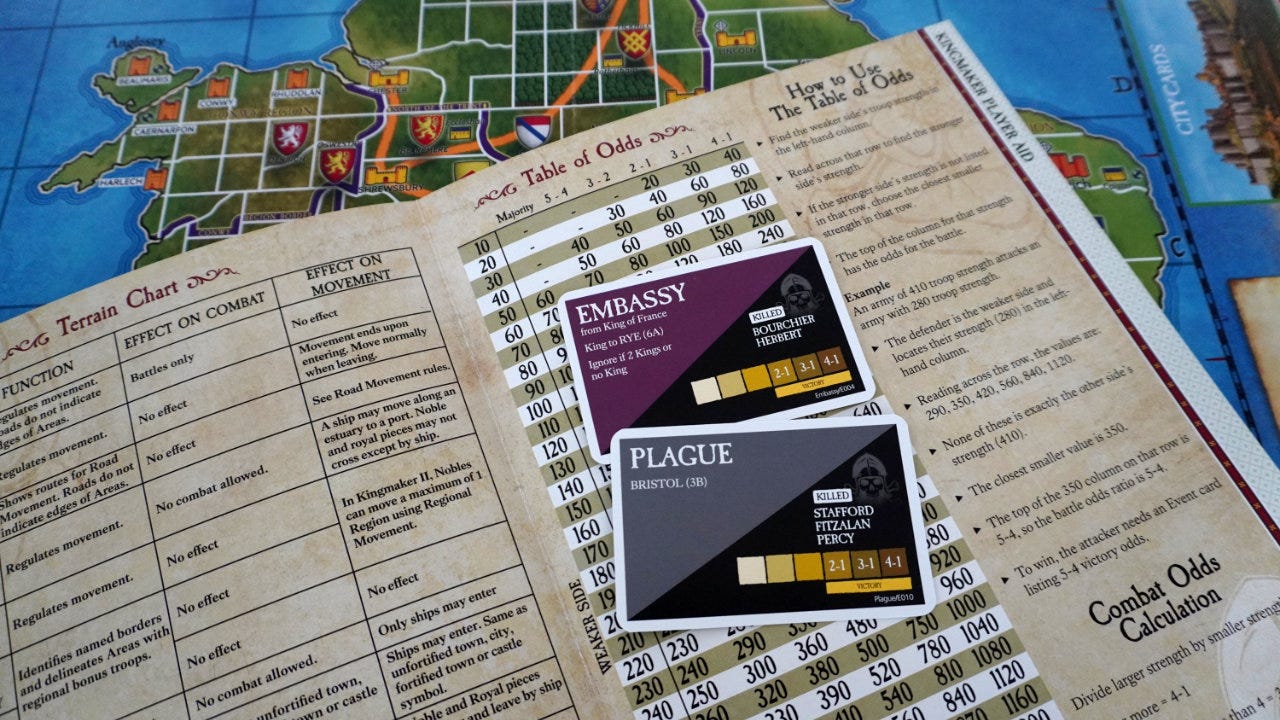

Drawing random event cards is a core part of the game. At the beginning of each player’s turn, they draw an event card and resolve its effects. It could be a Irish revolt, treachery, storms at sea, or a French raid. Most of these involve pulling a noble named on the card to a new location on the map.

A peasant revolt, for example, may pull the Constable of the Tower of London to St. Albans and the Marshal of England to Barnet. If you control nobles with those stations, off they go to their destinations, regardless of your plans for them — doesn’t matter if you just spent two precious turns marching them elsewhere.

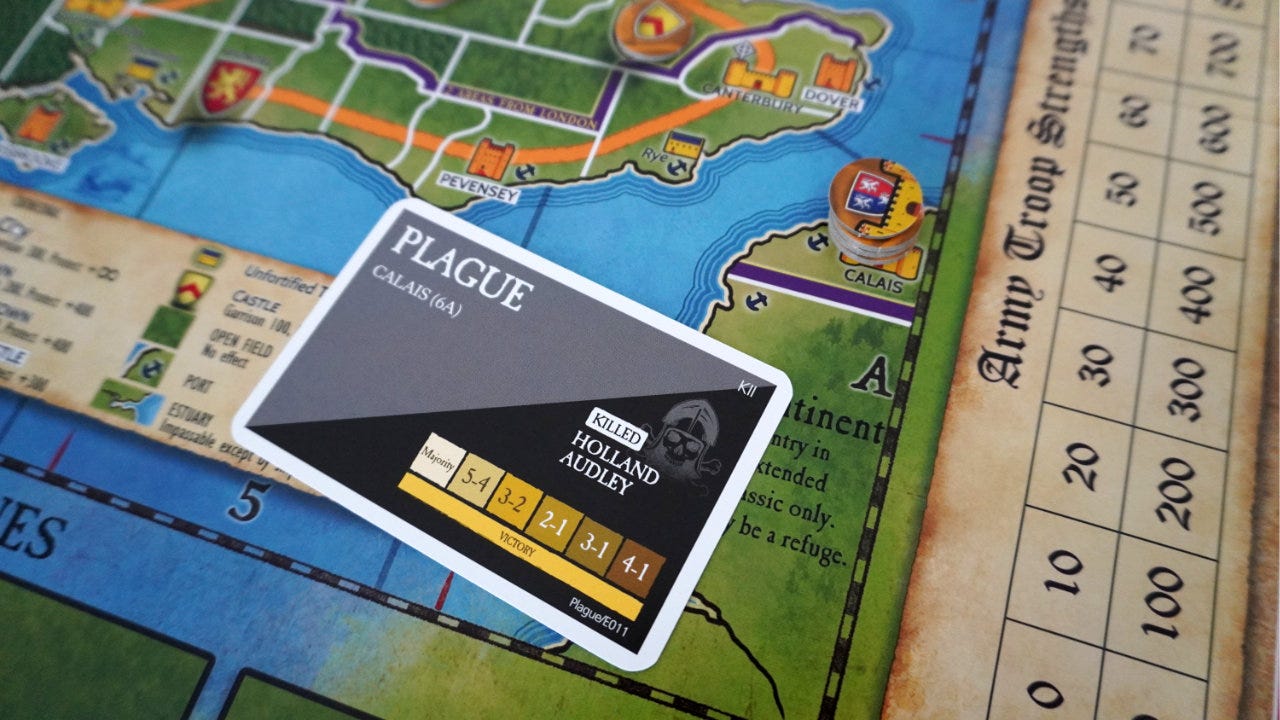

Similarly, a plague may strike a city: “All Noble and Royal pieces in the Towns or City named are killed.” That’s it. If you amassed your nobles and armies there — all dead. Last heir was hiding there? Dead.

In fact, our game played out in a related way. King Henry VI was randomly sent to Weymouth, making it easy for me to capture him with Beufort who starts the game right next door. The king was later called to Rye, yanking him out of the defense I’d built. Eventually, with just the king and one competing heir left, I slipped across the water to Calais… only to have a plague strike. Killing my armies, the king, and ending the game as a loss for me and a win for someone else.

Which generates some interesting questions: Was the outcome of the game random? Was it too random? What’s the point of a two hour game if it ends with a random card pull?

Randomness vs. theme

Here’s the thing: I really enjoyed my play of Kingmaker!

Moving ships to Dover, fighting a huge battle to a draw, and slipping off to Calais was exciting. It was high tension with our two faction separated by a strip of water, trying to strike a final blow. And then the only “Plague in Calais” in a 140-card deck was pulled.3 That’s a stand-up-from-the-table-and-shout sort of moment. And one I won’t forget any time soon!

But consider the same thing in a fully abstract game — a game that lacks any meaningful layers of theme.4 Playing Go where random cards move your pieces as you play and can end the game at any time. I doubt that would be a satisfying experience.

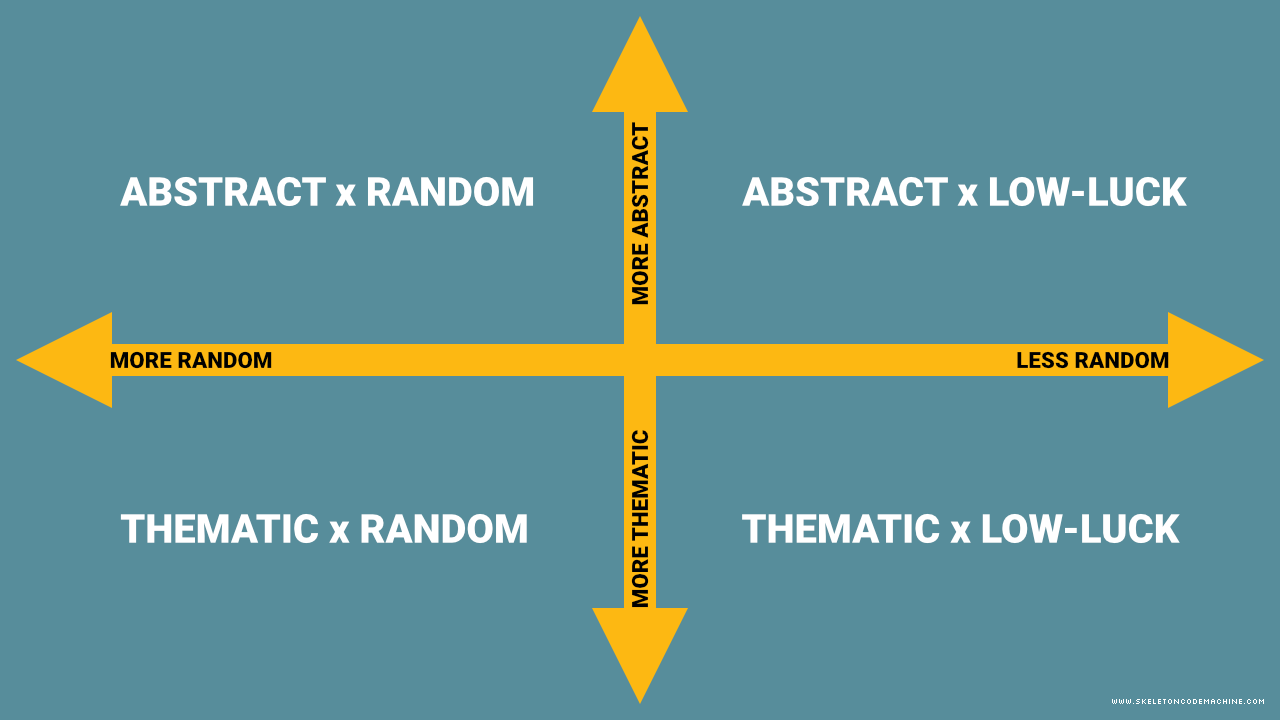

A model of randomness and theme would be helpful. We can build a quadrant chart with random vs. low-luck (i.e. limited randomness) on one axis and thematic vs. abstract on the other:

Four archetypes of games emerge from this model:

Abstract x random: Dice games like pig and simple children’s games that use roll and move as a mechanism. Rock, paper scissors and roulette, too.5

Abstract x low-luck: Chess and Go are the classic examples. They both have no hidden information, no dice or cards, and zero luck — a pure test of skill.

Thematic x low-luck: Concordia (Gerdts, 2013) may not be zero-luck, but it’s very low-luck in practice. Players play a fixed hand of cards vs. from a random deck.

Thematic x random: Dice-heavy games like Nemesis (Kwapiński, 2018) and card games like Moon Colony Bloodbath (Vaccarino, 2025).

Most games don’t neatly fit into one of these four categories. Instead, they are somewhere in the middle, a mix of luck and choice or an abstract game with thematic elements. That said, we can see some patterns emerge:

The Abstract x Random quadrant contains children’s games and games primarily used for gambling. It also includes games that exist as a way to facilitate socializing like bunco (“a fun dice game with no skill required”) and the original Fluxx (Looney & Looney, 1997). They provide a kind of fun, but the game is secondary to the experience of playing with others. They don’t show up in the BGG Top 100 list.

The Abstract x Zero-Luck quadrant contains games that appeal to a very specific kind of competitive fun and yet don’t seem to reach the Top 100 list often if at all. These are the “thinky” games that feel like a puzzle to be solved — classics that have stood the test of time. The game of go was invented about 2,500 years ago, and I’d expect it to be around for 2,500 more.6

The Thematic x Low-Luck and Thematic x Random quadrants are particularly interesting to me. I would have guessed that Thematic x Random would be either frowned upon or at least a very difficult design space to navigate. But both contain some great games that target multiple kinds of fun. Nemesis is a highly random game, but one that creates compelling stories and memorable games.

Why are thematic games seemingly more flexible when it comes to randomness?

Randomness “makes sense” in some games

In Kingmaker, the game attempts to recreate 15th century England — a time when storms sunk fleets of ships and devastating plagues struck cities.

So it makes sense that those events are modeled in the game. It may cause a player to cry out in anguish when their ship carrying their army is lost at sea, but those sort of things actually happened.

Similarly, combat is resolved by adding up the size of each opposing force and then consulting a combat results table (CRT).7 The CRT is then compared to a random card draw that shows the minimum required odds to win. Players quickly learn that even outnumbering your opponent 2:1 may not be enough.

Is it improbable that an army outnumbering its opponent 3:1 or 4:1 might lose on the field of battle? Certainly — but not impossible. Countless examples exist of morale, weather, and other haphazard events leading to a smaller force defeating a much larger one.

It would almost seem odd to leave these “random” scenarios out of the game.

Randomness that can be planned around

The events in Kingmaker aren’t completely random (i.e. an equal probability of any card being drawn at any time).

Certain nobles are more important and are more likely to be called away on tasks. Plagues only strike cities. The king is only ever called to specific places. A known card becomes more likely to be drawn as the size of the remaining deck decreases throughout the game.8

Repeated plays of the game make these limitations and probabilities more evident, and become part of the strategy of the game — camping out where the king might appear or limiting the use of excessively-popular nobles. Yes, the Plague in Calais card is random and severe, but also a reason to not spend time sitting in Calais.

This type of randomness adds historical flavor and texture to the game. The random events must be reacted to and mitigated as they occur.

While the same amount of randomness might be intolerable in an abstract game, the acceptance of it is easier in a highly-thematic game.

Randomness creates memories

On a personal note, I play as many board games as I can each year and carefully log each play in BG Stats.9 I’ve been doing this for years, with hundreds of plays logged — game, winner, score, players, and location.

What I’ve noticed is that I easily forget the plays of low/no luck games. I certainly enjoyed them at the time and cherish the time spent with friends, but I might entirely forget the game. There are times I’ve had to look up a game in BG Stats to see if I’ve even played it, having no notable memories.

But I clearly remember the time a player lost their ships with catastrophically bad dice rolls in Arcs.10 I will always remember the time I was one or two turns away from winning Nemesis, only to open a door and have my face eaten by the queen alien. I will remember the plague in Calais that cost me the game of Kingmaker.

Our brains preferentially create stronger memories from exceptional and shocking events rather than routine and predictable ones. It makes sense then, in the context of games, that the improbable dice roll (be it good or bad) is what I remember — not the time we took the most efficient actions to get two more stone or wood resources to win the game.11

What about zero-luck TTRPGs?

All of the examples above involve board games, but TTRPGs provide an interesting insight into randomness as well. With their roots in historical wargaming, most TTRPGs rely on dice rolls (be they roll-over or roll-under) to resolve actions and events. Player characters have skills, abilities, and modifiers, but many systems still consider a 1 a critical failure and 20 a critical success. Some days the dice are cursed, and your high-level character can’t catch a break.

TTRPGs are highly-thematic games with a fair bit of randomness built into their systems. Much like Kingmaker, this randomness provides obstacles to be overcome and planned around. It also creates shocking moments of success or failure that create permanent memories and stories to tell.

I wonder if low/no luck TTRPGs could provide the same memorable moments, or if they would be more like euro-style efficiency games — fun at the time but never truly memorable moments. Or does the explicit story-telling of roleplaying games overcome the lack of luck and chance?

Diceless, resource-based TTRPGs by Spencer Campbell like Loot and Hunt attempt to answer this question:

“When a fight breaks out, you use a 6x6 grid to represent the adventurers and the various enemies and monsters they'll face. On their turn, adventurers use their weapons and magic items to power themselves up and take out their foes. Combat is all about positioning and managing the resources of your weapons, rather than rolling dice to hit and deal damage.”

This matches something Spencer mentioned in an interview with Skeleton Code Machine in August 2023:

“I think we see resource management in RPGs, but it's usually either not a big part of the game, or it's a really tedious part (like counting the number of arrows you're carrying). I think we can expand that concept of resource management to similar things like Action Point (AP) economies, and deciding what are you going to do with the AP that you have each turn. And that's just so much more interesting to me, mechanically, than rolling dice and allowing chance to dictate success and failure.”

It’s an interesting approach, and I look forward to trying TTRPGs that exist in the Thematic x Low-Luck quadrant — rather than allowing chance to dictate success and failure.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Different kinds of fun: You’ll never design a game that appeals equally to everyone. Some players despise randomness as it ruins their strategies and takes away their agency. Other players demand randomness because it is essential to the theme and narrative of the game. Before starting, think about who you are making this game for.

Mitigation and planning are important: Kingmaker works because the contents of the event deck, however large, is known — Mowbray commands a large force but will be dragged all over the map. The onslaught of disasters in The Wars of Marcus Aurelius are fun because you can react to them and change your plans accordingly.

Not all randomness is the same: I’ve been pretty loose with the term “randomness” but there are different types of randomness that can be used in games. Learn the difference between input and output randomness and how they impact player experience. Know when to combine them.

What do you think? Do you prefer random or low-luck games? What do you think of zero-luck TTRPGs?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. This is your last chance to get Tumulus 03. Kick open the door as your first of four quarterly issues. New subs started before September 1, 2025 will receive Tumulus 03 as their first. After that, new subscriptions start with Tumulus 04. All subscriptions always include four issues. Learn more: tumulus.exeunt.press

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

Kingmaker is briefly featured in the three-part series on kingmaking.

I say this in an endearing way, not as a critique.

Depending on which version and set of rules you use when playing Kingmaker, the deck might be as small as 99 card vs. 140. You get the idea though. It’s highly improbable to have drawn that exact card at that time.

Examples of themeless games include backgammon, poker, and Qwirkle (2006). I’d argue that even “abstract” games such as Cascadia (2021), Azul (2017), and Harmonies (2004) do have themes even if they are lightly applied.

I look forward to comments from competitive Pro League RPS players explaining how it is actually a low-luck game of strategy much like chess.

This, of course, depends heavily on humanity’s temporal range.

The Complete Book of Wargames (Freeman, 1980): “If the die is the hammer of chance, the Combat Results Table is the anvil of probability. Very simply, the CRT is a collection of the results of outcomes of battles fought at each of the specified set of odds. … The CRT ensures that the results are not merely haphazard by altering both the outcomes that can occur in any particular column and the odd that any given outcome will occur.”

This is a game where repeated plays and knowledge of the deck provide a significant advantage when playing. The fact that such an advantage exists is proof that the game is not fully random.

Not sponsored. :)

Now referred to as the Battle of Delta 3 based on the map sector.

It is worth repeating that this is not a critique of euro-style board games. I really enjoy playing those games and find them fascinating. My point is not a value judgement of which style of game is better (a fool’s errand at best), but rather which game moments are burned into my long-term memory with greater clarity.

Fascinating and great article :D generally, i think i agree, that thematic with some nice randomness is really great :) that said, i still voted for Thematic x Low-luck, and that is because one of the most memorable games i've played is a zero-luck TTRPG: Wanderhome by jay dragon. It is built on the "Belonging Outside Belonging" system, which started with Dream Apart/Dream Askew (by Benjamin Rosenbaum/Avery Alder), which in turn started as "Powered by the Apocalypse" (PbtA) games, but removed dice rolls (and all randomness). You still have playbooks, but instead of moves/stats and such per se, you have a bunch of extremely evocative "picklists" which give a lot of flavour – and, they generally use some kind of "token" system. Essentially, you can gain tokens by doing something that is broadly defined "disadvantageous"/complicates things for you, and spend them to do "beneficial"/solving things. There are also often some kind of playbooks for the setting as well, and anyone can pick those up – the games are often described as either GM-less or GM-full, as everyone kinda shares the responsibility of a classical GM role, being able to judge exact outcomes and such ^^ also, playbooks generally have a list of things they can "always do", that don't feed into the token economy, but provide great suggestions for roleplaying!

Wanderhome is the only Belonging Outside Belonging game i have played, though i've also read Extra Ordinary by Kodi Gonzaga; and not that much either, but, the memories i have from those few sessions, or even just character creation, are so vivid and amazing. i can highly recommend giving them a chance (haha), and i myself would love to play more games using the framework (as well as more of the one i have) :)

What really is a zero-luck game? First-player victory proved and I go first? Is that still a game or just solving the Rubik’s cube?

What if my opponent — rather than dice — is a source of randomness? Do we ever know that not to be the case?

If there were an abstract game version of plague in Calais — on some squares, under some conditions, my stone might change colour — would that detract from the experience of playing the game, or would it just make it harder or less compelling to tell stories about ‘that time when …’ later?