Limited communication in Glatisant

Exploring how Glatisant, a GM-less TTRPG for two players, uses specific communication limits and a secret victory condition to create an Arthurian story. Also: Vote in the Bloggies!

Last week we asked if lane battlers are actually area control games.1 The poll results at the end of the article were particularly interesting, and I’m not sure what to make of them. If you have theories, please let me know in the comments.

This week we are exploring Glatisant, a GM-less tabletop roleplaying game for two players with an Arthurian setting. It uses limited communication and hidden victory conditions in an interesting way.

The Bloggies voting is open now!

Both Everything is Pointcrawl (Theory) and Playing the Chaplain’s Game (Critique) were nominated this year. You can vote for them in their respective categories. Also, you can listen to both of them as part of the new We Read the Bloggies podcast.

Glatisant

I’ve always been fascinated with Arthurian legends and how strange many of them are. Reading through Roger Lancelyn Green’s King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table is a wild ride.2 Someone on a horse is always riding into the middle of the feast hall and then they all go off on quest — to retrieve a “white brachet” for example.3

So I was excited to try Glatisant, a two-player Arthurian tabletop roleplaying game, written by Lucas Zellers, layout/design by Emily Entner, and published by Graftbound Press.4

Glatisant is a GM-less, asymmetrical TTRPG that uses the card-based Carta System by Peach Garden Games — the same system as Moon Rings.5 In the game, each player has one of two roles:

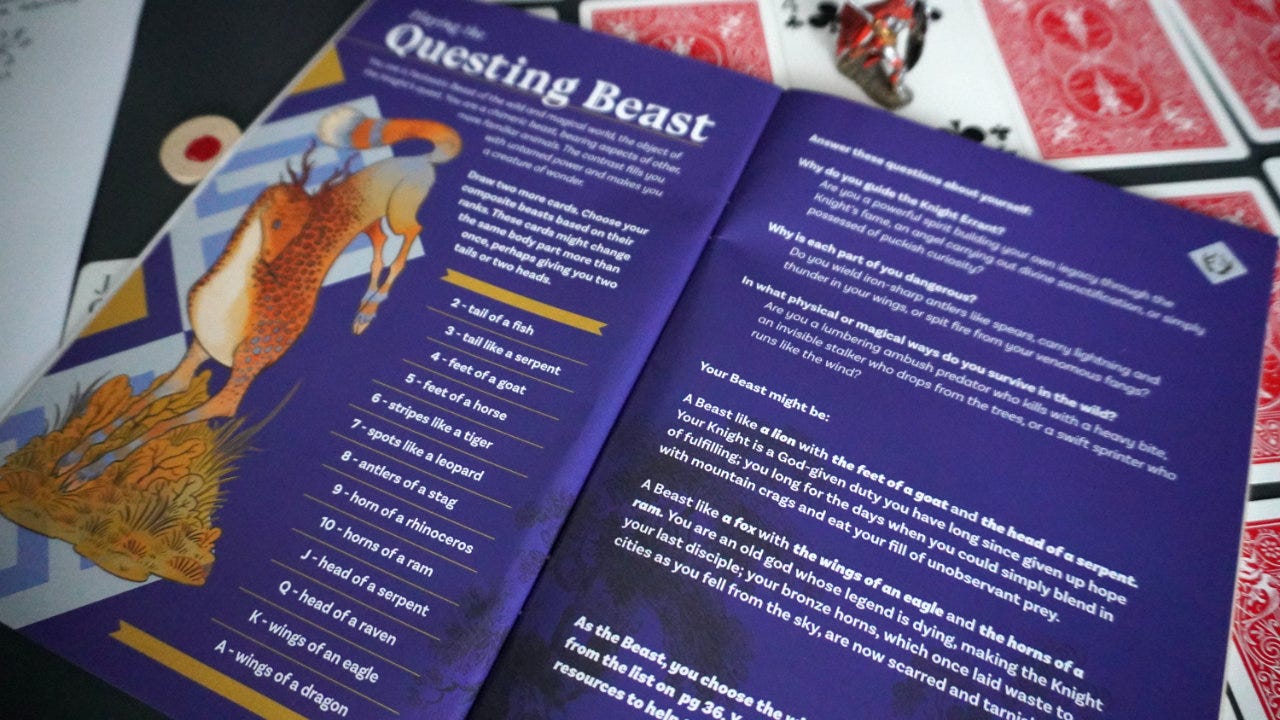

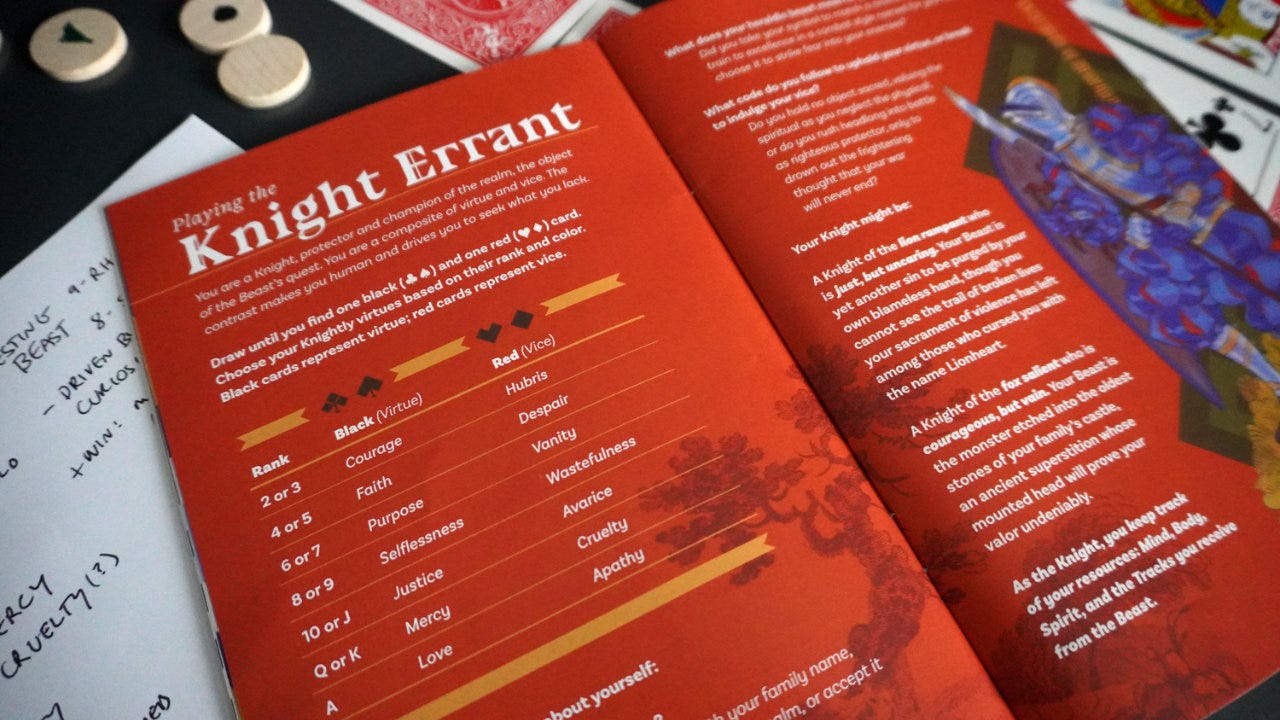

“You play as the heroic Knight Errant or the enigmatic Questing Beast, object of their quest. The Knight must capture the Beast, and the Beast must help the Knight become worthy of their legend.”

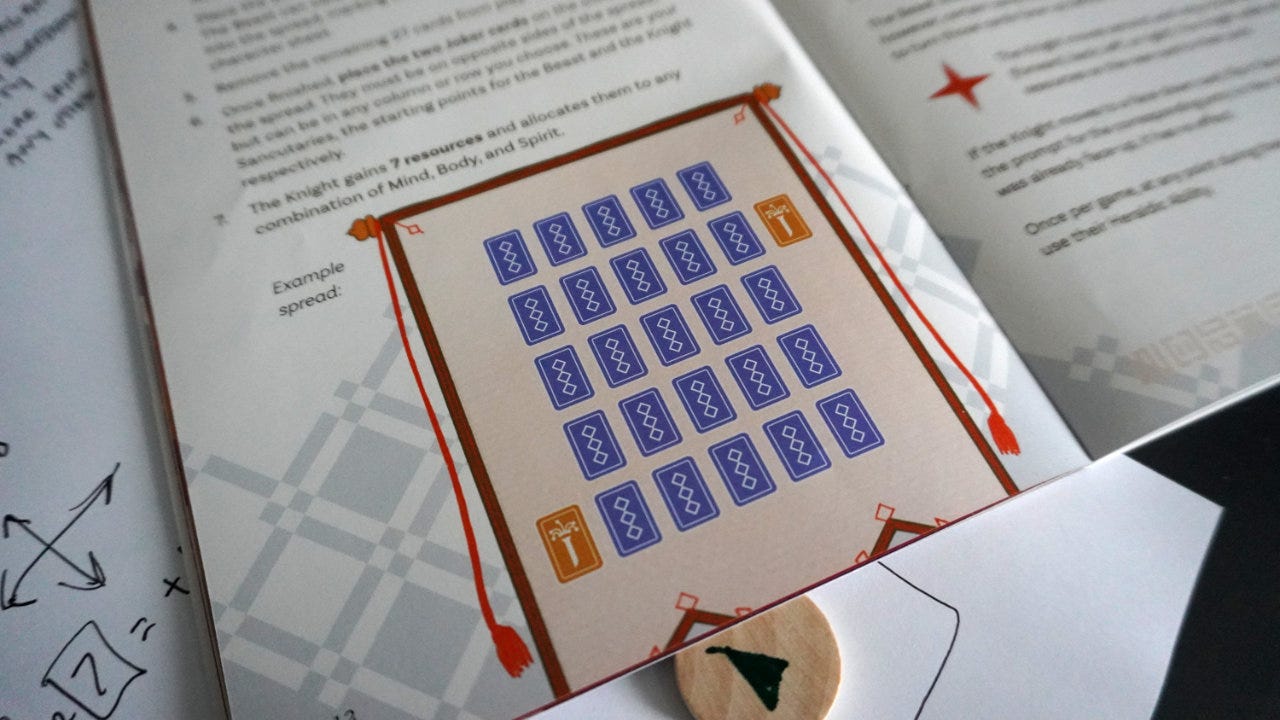

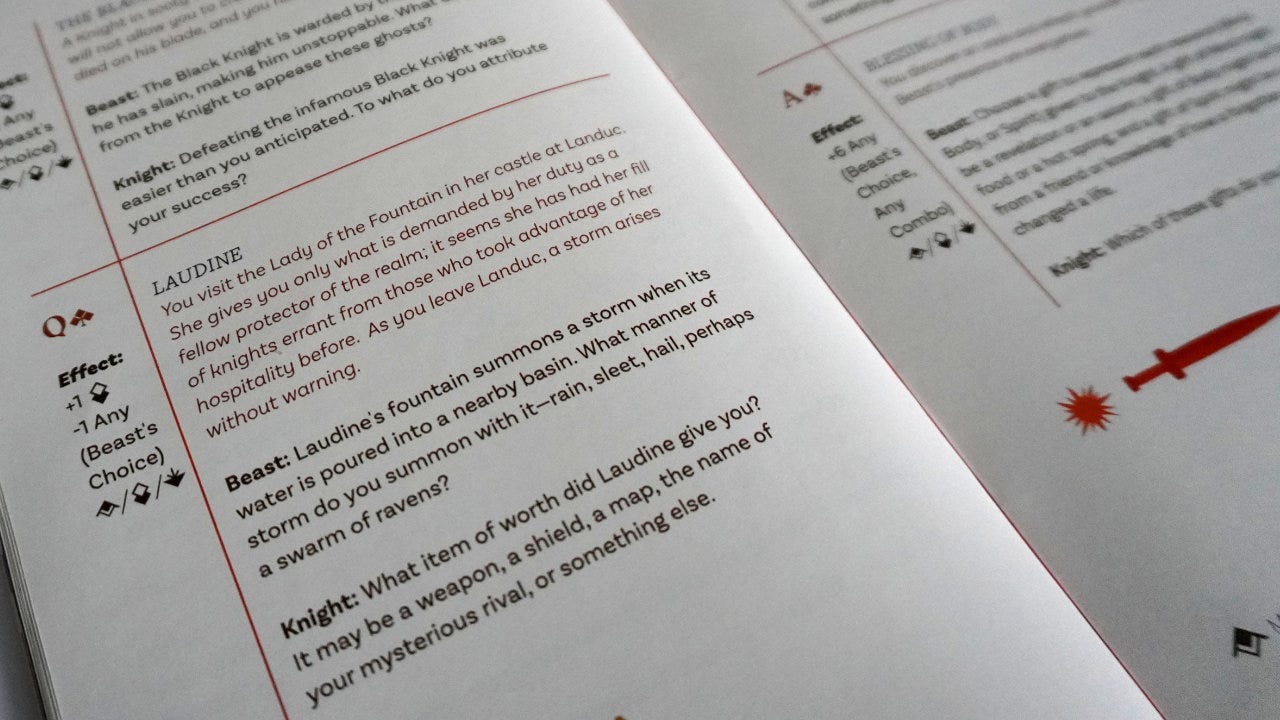

After selecting roles, 25 cards are arranged on the table in a 5x5 grid. The Knight starts on one side and the Beast on the other. As the knight moves from card to card, they are turned up and revealed. Each card has an associated narrative prompt. For example, the 5 of Hearts:

BITTER DISAGREEMENT: Your quest leads you into a loud or hateful argument with someone you trust. Beast: Which of them is right, if either? Knight: Who do you argue with, and why?

What is interesting about the game, is how it uses resources, hidden victory conditions, and limited communication as mechanical tools to tell the story.

The knight errant and questing beast

The game is asymmetric, meaning that each player has their own rules and abilities, with Root (Wehrle, 2018) being the example most people are familiar with.6 But while Root is a competitive game, Glatisant is a cooperative one. Both players need to work together to achieve the game’s victory condition, but how they do that is a little tricky.

Here’s how the two roles are structured:

The Questing Beast: A “fantastic Beast of the wild and magical world” that serves as the object of the Knight’s quest. This player chooses the hidden victory condition from a list at the back of the book. They have more freedom of movement, being able to move both orthogonally and diagonally around the cards. And they do not reveal the cards as they move onto them, but may drop “trail” resources to indicate where the Knight should go.

The Knight Errant: A “protector and champion of the realm” and focus of the Beast. The Knight doesn’t know what the victory condition is, only that they must hunt the Beast. They can only move orthogonally, revealing each card as they do.

The Knight also has a set of resources including Mind, Body, and Spirit, tracked with dice or tokens during the game.

Each revealed prompt will increase or decrease one or more of the resources. Sometimes the Beast will be allowed to choose which ones change. Other times the prompt will dictate the change. The Tempest will decrease the Knight’s Body by 2 but an encounter with Merlin the Magician will increase Mind and decrease Spirit.

These resources are important because they are tied to the victory condition.

Secret victory condition

This is not a hidden movement game. The Knight knows where the Beast is located on the 5x5 grid at all times. The game does not end in victory if the Knight “catches” the Beast.

Instead, the Beast is trying to secretly guide and help the Knight. This is represented by the “Win Conditions” in Glatisant. Arranged into Easy, Medium, and Hard, they are a mix of theme and mechanism. Mechanically, the condition might require the Knight and Beast meet at the center of the grid or that the Knight has more Spirit than any other resource when they meet the Beast. Thematically, the condition might be that “only the strong” may find the Beast or “only when you have reached the end of yourself” can the Beast be found.

The key rule is that the Beast may never reveal the victory condition to the Knight directly. They may only guide the Knight by their choices in the game.

This results in the Beast and Knight working together but in an indirect way. They can incorporate hints into their narrative answers. The Beast can leave trails to guide the Knight to a particular card.7 Back and forth, they move, reveal cards, narrate prompts, and adjust the Mind, Body, and Spirit resources.

The players continue until the Beast and Knight meet on a card at which point the victory condition is (secretly) checked. If not met, the game continues. If all 25 cards have been revealed and/or the Knight has exhausted all resources, then both players end the game in defeat.

Limited communication

I have a complicated relationship with limited communication mechanisms in tabletop games. For example, I find it frustrating when a game outlaws communication but then tacitly requires it for the game to function, as I mentioned in the How fragile is your game design? article from 2024:

Limited communication co-op games: In games like The Crew: The Quest for Planet Nine (Sing, 2019) and The Mind (Warsch, 2018) the rules explicitly say that players may not talk and may not openly coordinate what they are doing. Yet the games won’t work if there is absolutely no communication. So players end up developing their own ways to communicate without explicitly communicating, using subtle hints or body language. In this case, the players must almost act contrary to the explicit rules to have the game work as intended.

I also find it frustrating when cooperative games say players can’t discuss cards and specific action details to cooperate, as a strict reading of the Gloomhaven (Childres, 2017) rulebook would indicate:

“Players should not show other players the cards in their hands nor give specific information about any numerical value or title on any of their cards. They are, however, allowed to make general statements about their actions for the round and discuss strategy.”8

But other times, the limited communication doesn’t seem to get in the way of the game for me. I’d include Sky Team (Rémond, 2023) in that category.

Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised to see the limited communication structured the way it was in Glatisant.9 The players can play their roles and respond freely to prompts. The Knight has effectively no restrictions on communicating, as they have no information to hide. The Beast can say and do almost anything other than sharing one very specific victory condition.

The limit imposed on in-game communication is clear, precise, and makes thematic sense (i.e. the Beast can’t talk).

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Public domain settings: I doubt I’ll ever tire of classic settings such as Robin Hood and Arthurian legends, but I realize they aren’t for everyone. There are, however, so many public domain settings that are just waiting to be adapted into new and interesting games: The Scarlet Pimpernel, Treasure Island, The Call of the Wild, just to name a few.

Hidden victory conditions: Glatisant uses a single, secret victory condition that determines if both players win or lose together. In other competitive games like Troyes (Dujardin, Georges, et al., 2010), each player has their own hidden objective but everyone scores all objectives at the end of the game. Two very different applications that demonstrate how hidden objectives are such an interesting area of exploration in game design.

Limited communication: Love it or hate it, limited communication can be an interesting mechanism in games. I appreciate how the limits are very tight and specific in Glatisant while allowing freedom in responding to the prompts.

What do you think? Do you appreciate limited communication mechanisms in games? Do you think there are significant differences in how The Crew, Gloomhaven, Sky Team, and Glatisant approach limited communication? Which style do you prefer?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want more in-depth and playable Skeleton Code Machine content? Subscribe to Tumulus and get four quarterly, print-only issues packed with game design inspiration at 33% off list price. Limited back issues available. 🩻

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

My favorite comment was from Aaron Lim on Bluesky: “lane battlers are just area control games which are just auctions which are just drafting”

Roger Lancelyn Green is well known for his children’s books that adapt classic tales into something suitable for a younger audience. I found The Adventures of Robin Hood (1956) was particularly enjoyable, with each chapter working as both a stand-alone story but also tied into the overall narrative arc of the book. Another notable bit is that Green encouraged C.S. Lewis to publish The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

A brachet is a small hunting dog. I don’t recall all the details, but I remember so much violence and bloodshed over this little white dog.

The Questing Beast was called beste glatisant in Old French: “Its name comes from the great noise that it emits from its belly. Glatisant is related to the French word glapissant, ‘yelping’ or ‘barking’, especially of small dogs or foxes. Arthurian scholars tend to interpret the beast as a reflection of the medieval mythological view on giraffes, whose generic name of Camelopardalis originated from their description of being half-camel and half-leopard.”

I wrote about the Carta SRD as part of the article on player agency in February 2024, including a few examples of how it could be used and modified. If you want to try your hand at game design, it’s not a bad place to start.

Although we don’t necessarily call it that, I’d argue most TTRPGs are asymmetric as well. Each character has their own abilities and even if they are all using the same overarching ruleset (e.g. Mothership or D&D 5e), each one is only using a subset of those rules. A fighter may not interact with the spellcasting rules while a wizard may not interact with brawling rules. Does it fit a strict definition of asymmetry in games? I don’t know. Feels asymmetric to me. Massive Darkness 2: Hellscape takes this idea and gives each character class their own unique mechanisms.

The Beast is allowed to know what all the face-down cards are at the start of the game. In addition, the rules note that the cards should be selected to ensure each game is winnable.

The Gloomhaven rulebook does have a game variant that allows open information, but it is not recommended: “Additionally, if they wish, a group of players may also play with fully open information by increasing the difficulty in the same way as for solo play. Playing with open information means that players can share the exact contents of their hands and discuss specific details about what they plan on doing. This is not the recommended way to play the game, but it may be desirable for certain groups.” Emphasis in the original.

Writing this article really has me wondering why I’m so opposed to limited communication in some games and don’t mind it at all in other games. I’m not sure I have a clear answer to that, and it’s worth thinking about. Perhaps a topic for a future article.

The original post did not include links to Glatisant! Here they are...

PDF: https://graftbound.itch.io/glatisant

Print: https://graftbound.com/product/glatisant/

I feel like Arthurian stories often have a theme of having a goal but not knowing its true nature or consequences. Or conversely, the sense that the outcomes are preordained. The limited communication in Glatisant, and the Beast's manipulations, seem to combine to create a very Arthurian story: the Knight appears to be pursuing a random Beast but is actually moving inevitably towards their own destiny. I'll have to try out.