Are lane battlers actually area control games?

Exploring lane battlers and area control via the example of Air, Land, & Sea. How far can we modify a lane battler by adding thematic elements before it comes a "troops on a map" area control game?

I’m happy to announce that Skeleton Code Machine’s “Playing the Chaplain’s Game” has been nominated for The Bloggies, a “yearly celebration of blogging in tabletop roleplaying games.” Unlike most awards, nominated blog posts face each other in a tournament-style bracket. There are multiple rounds of voting, eventually resulting in a single winner. The next round of voting begins February 16, 2026.

Last week we looked at how Moon Rings uses a card-grid to create a journaling game with fingers as resources.

This week we are taking a look at lane battlers, using Air, Land, & Sea as a key example. Then we’ll explore how far you can stretch a lane battler until it becomes a “troops on a map” area control game.

Air, Land, & Sea

The theme of Air, Land, & Sea (Perry, 2019) is fairly straightforward with art vaguely reminiscent of the Second World War: “As Supreme Commander of your country’s military forces in Air, Land, & Sea, you must carefully deploy your forces across three theaters of war: air, land, and sea.”

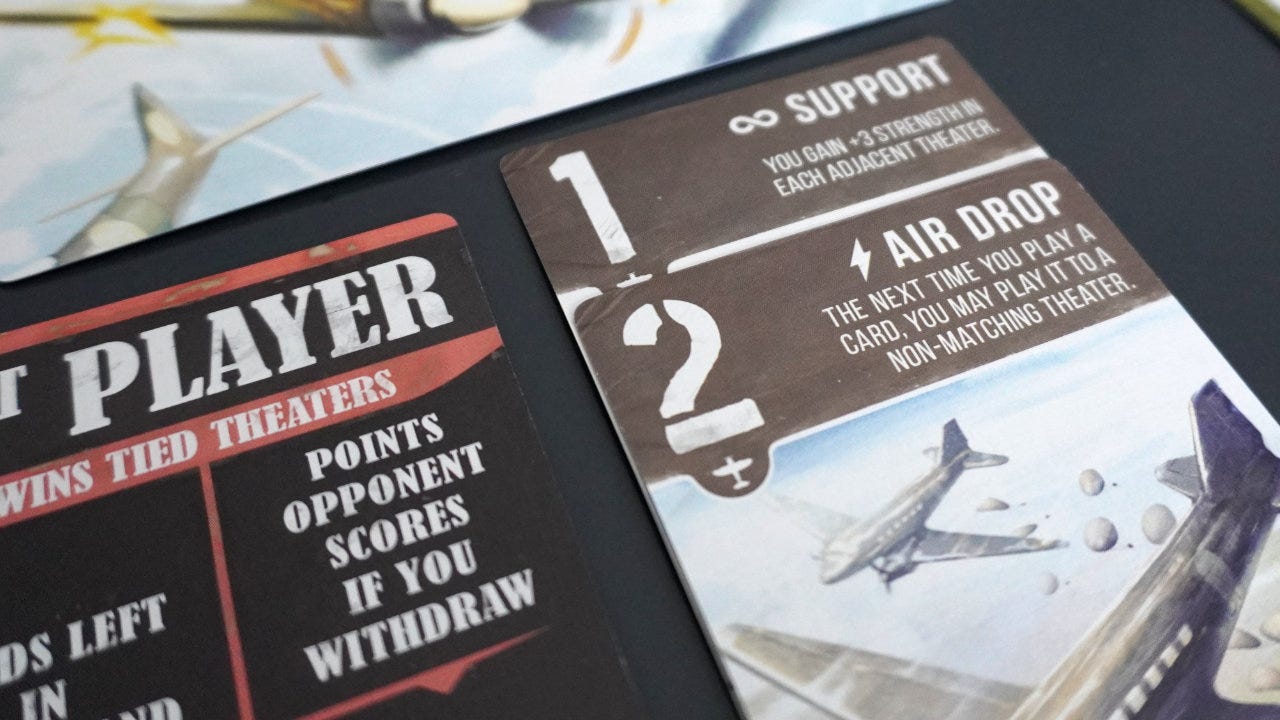

Two players sit across from each other with three “theaters of war” cards in a line between them: Air, Land, and Sea. Each player is dealt six cards, each tied to one of the theaters much like a card suit. The cards also have a numerical strength and sometimes have a special ability that is triggered when played. For example, the Transport (Air, Strength 1) card has the ability: “You may move 1 of your cards to a different theater.”

In addition, cards can be played face down into any theater regardless if it matches or not. Cards played this way always have a strength of 2.

After all the cards are played or someone decides to withdraw, the strength of each theater is totaled and the player with the highest value controls that theater.1 Each theater is resolved on its own, independent of the other theaters.

The player who controls the most theaters (2 of 3) is awarded victory points. The first player to reach 12 victory points wins.2

Lane battlers

Air, Land, & Sea is a perfect example of a lane battler game:

Play is divided into multiple lanes.

Cards are played onto opposing sides of each lane.

Each lane has its own distinct battle that is resolved independently of the other adjacent lanes. Although lanes may interact during play.

Overall victory is determined by winning control of individual lanes.

The three lanes (Air, Land, and Sea) are resolved based on total strength and victory points (VP) are awarded for controlling the most lanes (2 out of 3).

I’ve talked about lane battlers before in the context of Compile, a game heavily influenced by Air, Land, & See and that also uses three lanes.

In the case of Compile, however, each lane has two types or labels versus just one like in Air, Land, & Sea. For example, a Compile lane might be both Spirit and Life which allows either suit to be played into that lane. Also, the ability to shift/swap the lanes is a key part of the game and each card has multiple abilities that trigger based on different criteria.

It’s just one of the 81 games currently categorized as lane battlers on BGG, with the top ones being: Radlands (2021), Hanamikoji (2013), Battle Line (2000), Air, Land, & Sea (2019), Schotten Totten (1999), and Blood Bowl: Team Manager — The Card Game (2011).

Schotten Totten is a particularly notable example by Reiner Knizia that uses nine lanes.3 Rather than total numerical strength, players try to get ranked combinations of cards: color run, three of a kind, matching colors, or a run of successive values. A player wins when they either control three adjacent lanes or any five lanes.

Lane battlers with more than two players

In most cases the lane battlers are for two players only. While not impossible, a three player lane battle would have to look like a triangle on the table perhaps.4 It gets complicated if everyone’s cards are the same (i.e. pulled from a common deck).

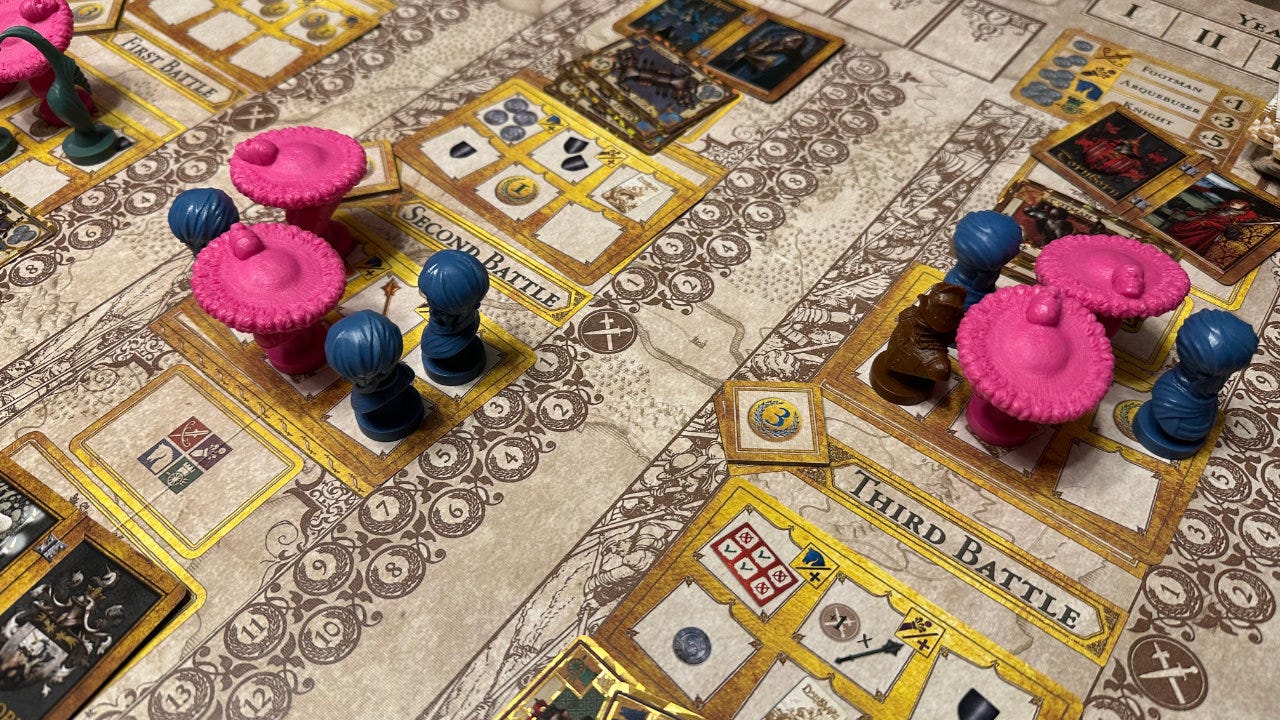

Dogs of War (Mori, 2014) supports 3 - 5 players competing for three lanes. It does this by adding player-specific minis (with fancy hats!) which are used to indicate support for the winning side of each lane battle.5 The cards are from a common pool, but the addition of unique components and player colors allows for more than 2 players.

Are lane battlers actually area control games?

Games like Air, Land, & Sea, Schotten Totten, and Compile are all clearly lane battlers, sharing much of the same mechanical DNA. Games like Dogs of War, however, seem to be less like a lane battler and closer to an area control or area majority game.

This made me wonder if lane battlers are just one-dimensional area control games. If we represented the lanes as a map but retained the same basic mechanisms, would that change how we think about the game?

To test this, let’s look at a few different theoretical iterations of a lane battler design.

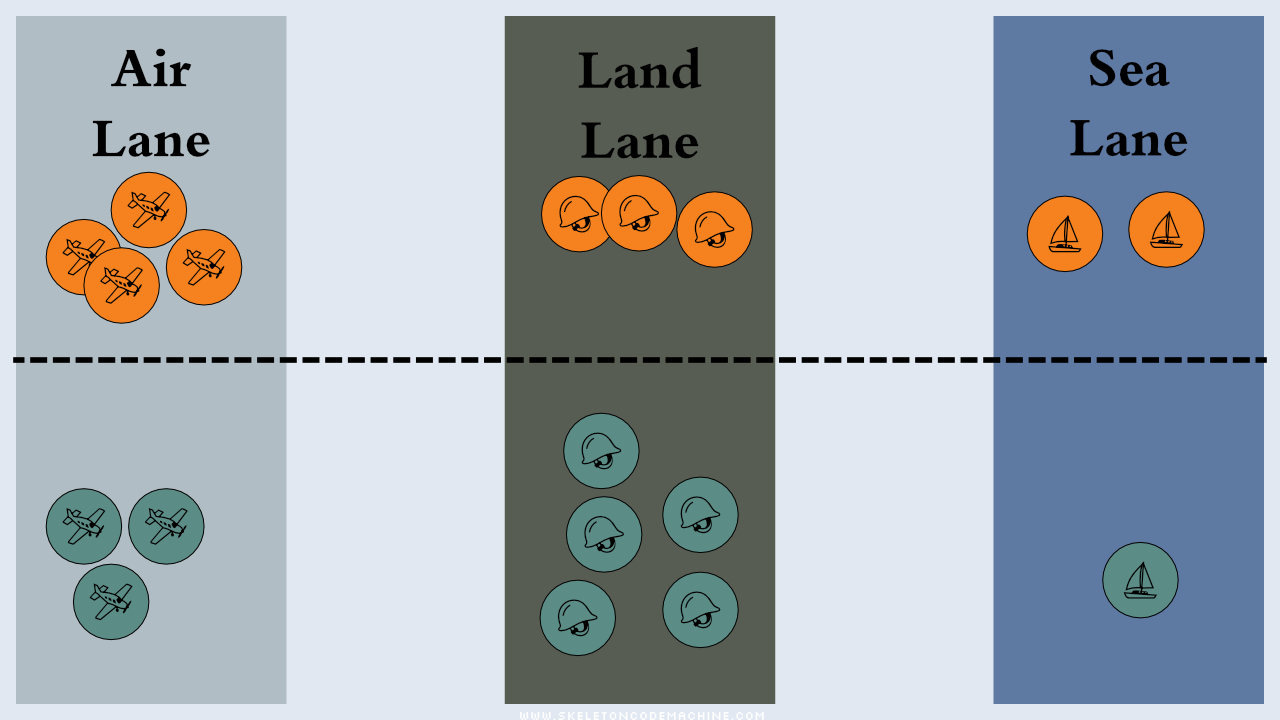

Iteration 1: Abstract lanes

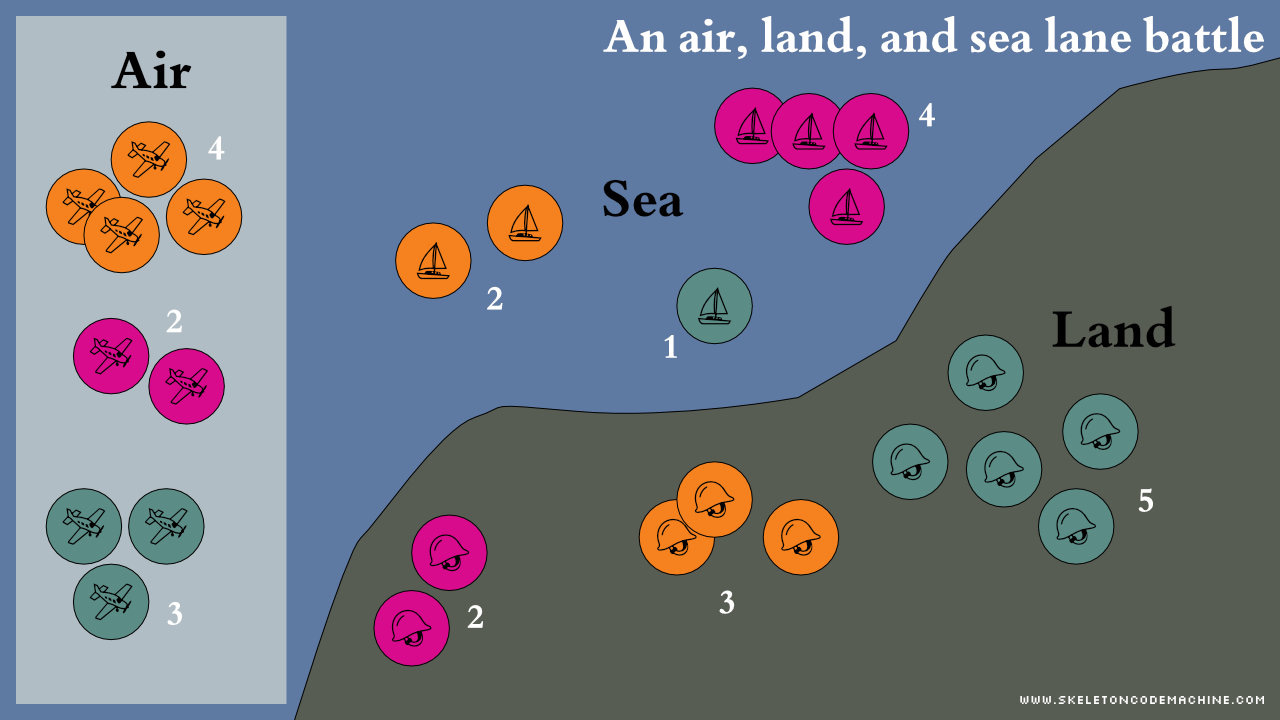

First, imagine Air, Land, & Sea, but each player had colored tokens representing their strength rather than cards:

That definitely still looks like a lane battler. There are three clearly distinct lanes that are abstract representations of the theme. Each player places tokens on their side of each lane and then each lane can be resolved one at a time.6

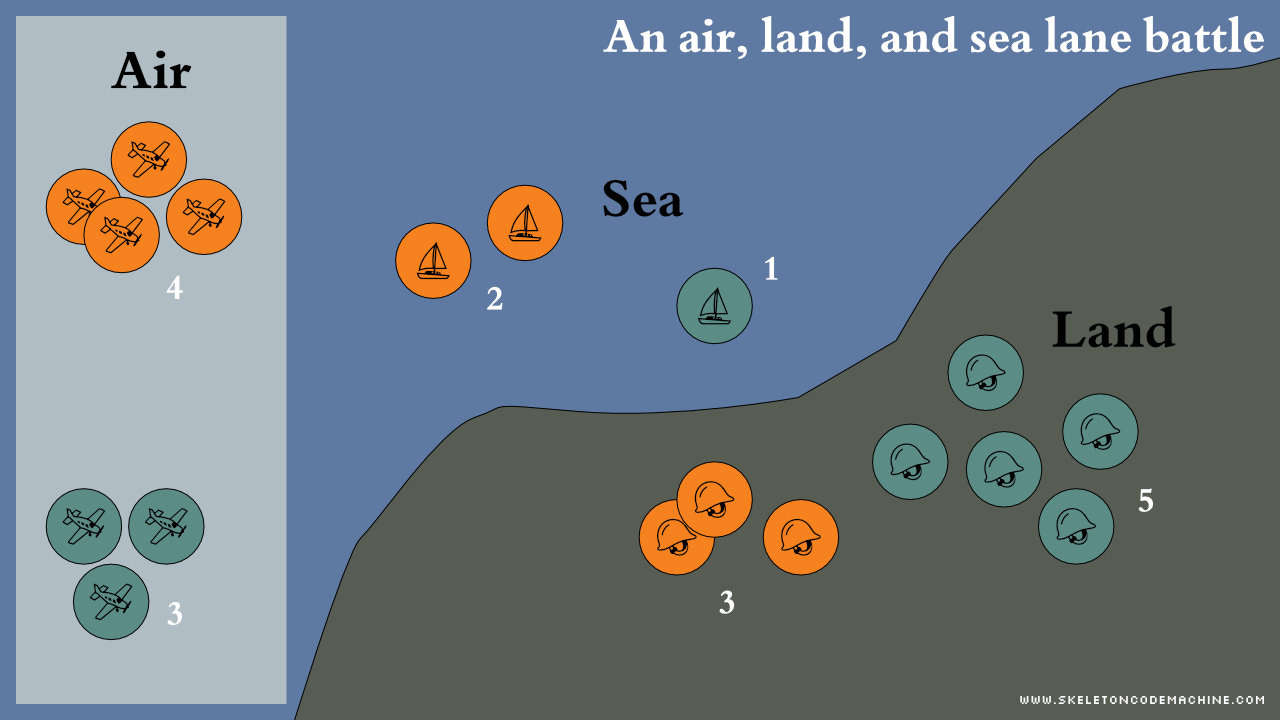

Iteration 2: Thematic lanes

Next, let’s imagine that we represented the three lanes as a thematic 2D map rather than abstract lanes:

I think you’d be able to recreate Air, Land, & Sea in its entirety using a map like this. It wouldn’t look like a lane battler, but it certainly would still be one. In the example above, Orange wins Air and Sea while Green wins Land.

Iteration 3: Thematic lanes with 3 players

To continue with this thought experiment, this new map would allow us to easily have multiple players competing for each lane. They would each have tokens in their own color like this three-player example:

Now it looks even less like a lane battler and more like a classic “troops on a map” area control game. This is a three-way battle across three lanes. In this example, Orange wins Air, Pink wins Sea, and Green wins Land. Again, the tokens are shown as being all the same, but they could be different and each have their own special abilities.

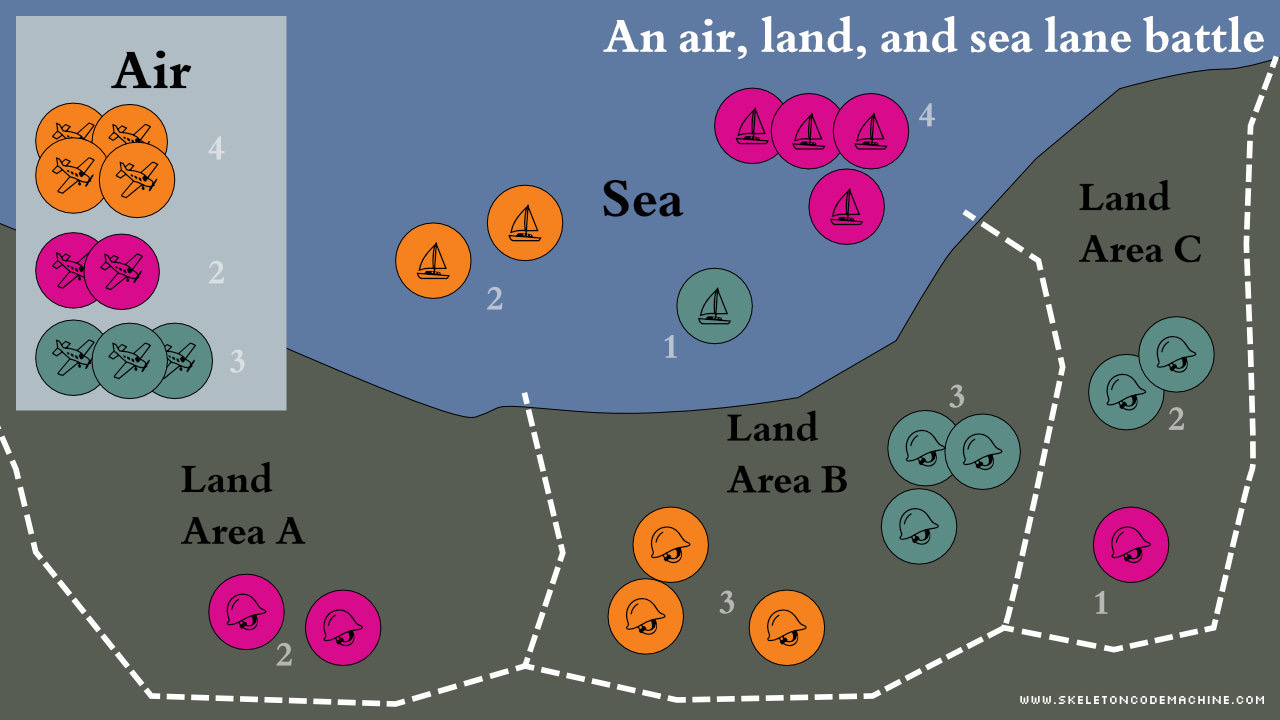

Iteration 4: More thematic lanes and 3 players

Finally, let’s expand this one more time. In this iteration, there are still three players but now the Land lane has been split into three separate lanes called Land Area A, Land Area B, and Land Area C. This gives us five total “lanes” and three players:

This looks even less like a lane battler and instead almost completely like an area control game. The lanes are almost unrecognizable because they are represented as 2D areas on a thematic map. The strength being played into each one is no longer shown as values on cards and instead must be calculated by inspecting each token and adding the associated values together.

Is this still a lane battler?

I don’t know. I’d argue that it could be very mechanically similar to one, but it no longer feels like one. Somewhere between the first iteration and the last, the concept of lane battling is lost.

Applying layers of theme

It’s a fun exercise to wonder how Air, Land, & Sea would be different with a thematic map and unique minis for each unit, but there are also practical considerations. By using just cards and a few VP tokens, the game can fit in a small box and be sold for a very reasonable price. It’s easy to set up, takes up very little table space, and could be played at a coffee shop. The lack of plastic components and large map is one my favorite things about the game.

The trade-off, however, is that it feels more like an abstract game. There’s really no feeling of a battle or war game.

It makes me think back to Sarah Shipp’s layers of theme. Specifically how by making the map thematic (i.e. showing the land and water in 2D), it makes them Layer 2 “baked-in thematic elements.” The shape of the land and how it borders the water becomes an integral part of the game that can’t be avoided when playing.

There is no right or wrong way when designing on the abstract vs. thematic continuum, but it is interesting to think about.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

An interesting design space: While Compile clearly takes much of it’s design inspiration from Air, Land, & Sea, it is a very different game. Even when sharing mechanisms like having three lanes and being able to play cards face down into any lane, it has unique a feel and far different strategies. Then consider Schotten Totten where the goal is to get runs and sets vs. numerical totals. There’s a lot of room in the lane battler family for new and interesting designs.

They are similar to area control games: I can’t help but see some similarities between lane battlers and area control games. Yes, they are different genres and styles of games, but a lot of that is how they are visually implemented.

Abstract vs. thematic: I tend to prefer highly thematic games rather than abstract ones, but the distinction between the two isn’t always clear. It is also possible to turn an abstract game into a thematic one without many mechanical changes. The challenge often comes in the component complexity that comes along with it.

What do you think? Have you played any lane battlers that you love? Which lane battlers have you played that support more than two players? Is it helpful to think about the distinction between a lane battler and an area control game?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want more in-depth and playable Skeleton Code Machine content? Subscribe to Tumulus and get four quarterly, print-only issues packed with game design inspiration at 33% off list price. Limited back issues available. 🩻

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

The ability to withdraw during a battle is really interesting. If you know you aren’t going to win control of enough theaters, you can just give up and concede the battle (i.e. withdraw). Your opponent wins points, but not as many as they would have if you had run the battle to its full conclusion. Instead of 6 VP, they might only get 2-4 VP depending on how many cards you have left in your hand when you gave up. It’s a clever way to turn garbage time into an interesting choice.

As always, this is not a full rules explanation nor is it a review of the game.

Schotten Totten is available to play on Board Game Arena. You should check it out.

There are rumors than M. Allen Hall has created a mutant, three-player version of Compile — something that I consider to be an abomination.

The upcoming Play to Z version of Dogs of War appears to have removed the fancy hats from the game. While this makes me a little sad, I’m very excited to see the new product and the art looks great!

For simplicity, I’m showing the tokens all the same in each theater. One could certainly imagine, however, different types of units that each had their own special abilities when played. Imagine each token shown in the diagrams as a unique mini with its own rules.