Moon rings, missing fingers, and teaching game design

Exploring how Moon Rings takes a simple card-grid and turns it into a journaling game about a witch hunting for rings in a dangerous labyrinth. And how I might use this in future game design classes.

Last week we looked at how Rauha (Goupy & Rivière, 2023) uses grid-based pattern and activation systems with tiles. Since then, I’ve realized it’s available on Board Game Arena (BGA) and have been able to play it a few more times online. Definitely worth checking out if you get the chance.

This week we are looking at Moon Rings, a solo journaling game from Junk Food Games about witches, blood moons, and the inevitable loss of fingers.

Using card grids in design workshops

I recently taught a tabletop game design class at the Gettysburg Library.1 It’s always fun to chat about games for an evening, but the attendees were particularly engaged and enthusiastic, so it was a really good time. The topics mirrored the crash course I taught at Dickinson College, but I had more time available. This allowed me to have more hands-on activities in each of the four design principles:

Know who your game is for.

Choose a theme and zoom in.

Design for meaningful choices.

Think about your game in three acts.

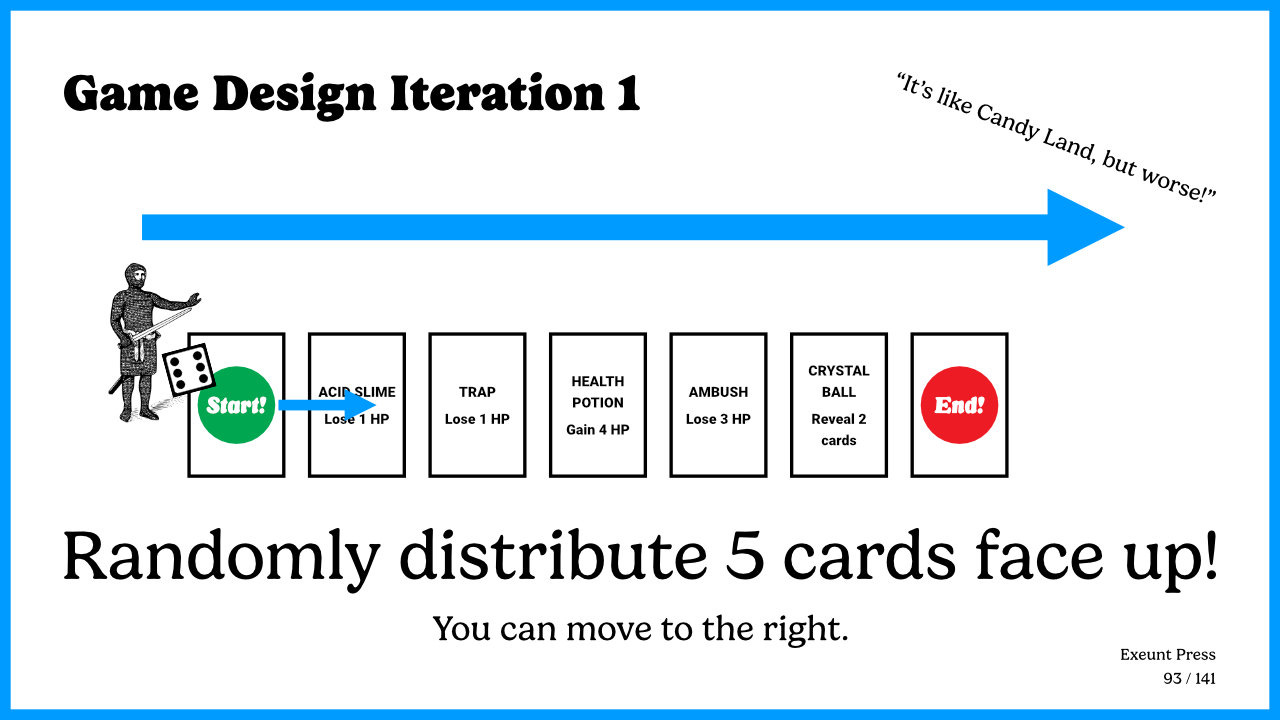

When learning about player agency and meaningful choices, we did what I jokingly call “The Worst Dungeon Crawl Ever” exercise.

Using cards and dice, we intentionally made a really bad game.2

Iteration 1 begins with zero player agency as the player is forced to move to the right each turn. It always results in a horrible player experience (as intended) and quite a few degenerate game states like infinite loops. From there, we do two more iterations to demonstrate how even adding the smallest touch of player agency can (ever so slightly) improve the game.

This exercise always goes over well. At the end I show how after the Nth iteration, you might end up with a game that is quite fun — like Mini Rogue (Di Stefano & Gendron, 2020).

It’s a hands-on way to demonstrate how adding player agency, resources, some graphic design, a story, dice, and other mechanisms can create a really interesting and compelling game.

Moon Rings

It was with that card-based dungeon crawl exercise in mind that I gave Moon Rings by Junk Food Games a try:

“The cursed Blood Moon hangs over this land always. It has brought ruin and despair to everything touched by its crimson light. You are a witch and cannot abide the reign of the Blood Moon any longer.”

As a witch, you must explore a labyrinth to find five moon rings hidden somewhere within — one for each finger. Find all five and the ritual site and you’ll change the moon, breaking the curse. Run out of blood or fail to find enough rings and the game ends in failure.

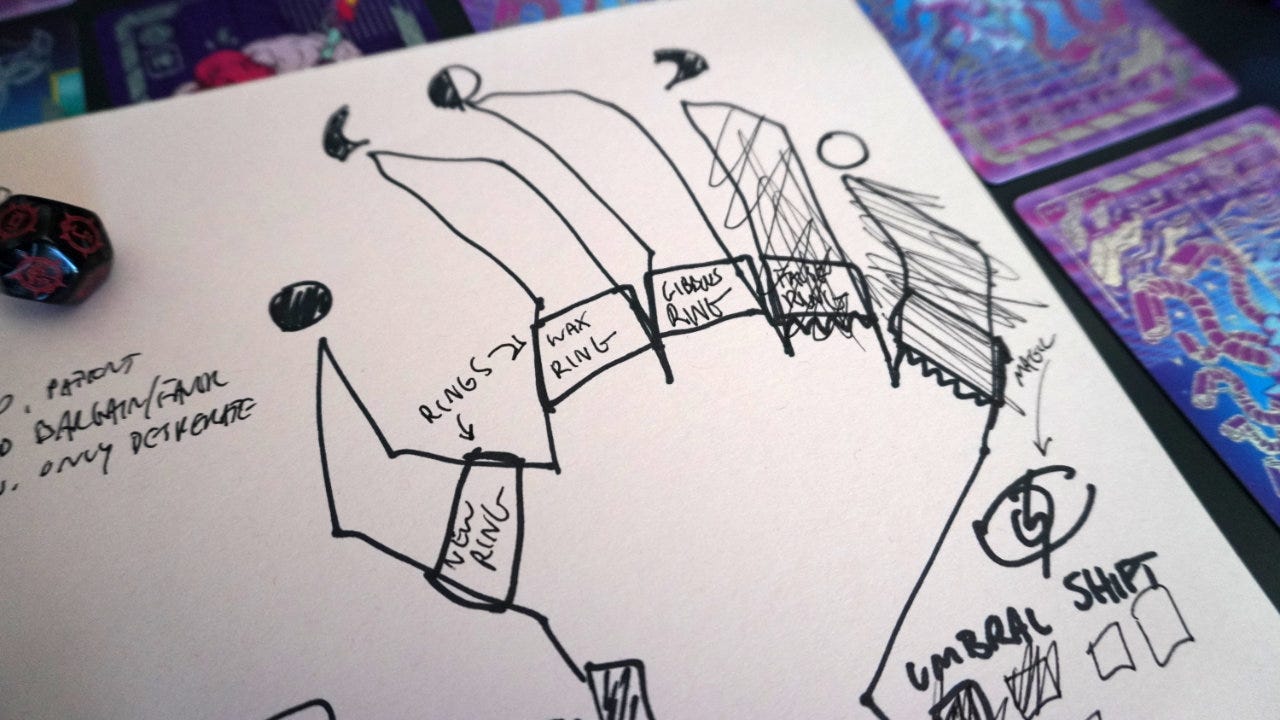

Gameplay in Moon Rings is based on the card-based grid described in the Carta SRD. Cards are shuffled and dealt out into a 6x4 grid of 24 cards. The player places the Ace of Spades along the outer edge, designating their starting location. Somewhere hidden in the face-down cards is the Ace of Hearts — the ritual site you must find.3

From there, the core game loop has just three steps:

Explore: Move to a new, adjacent card and reveal it.

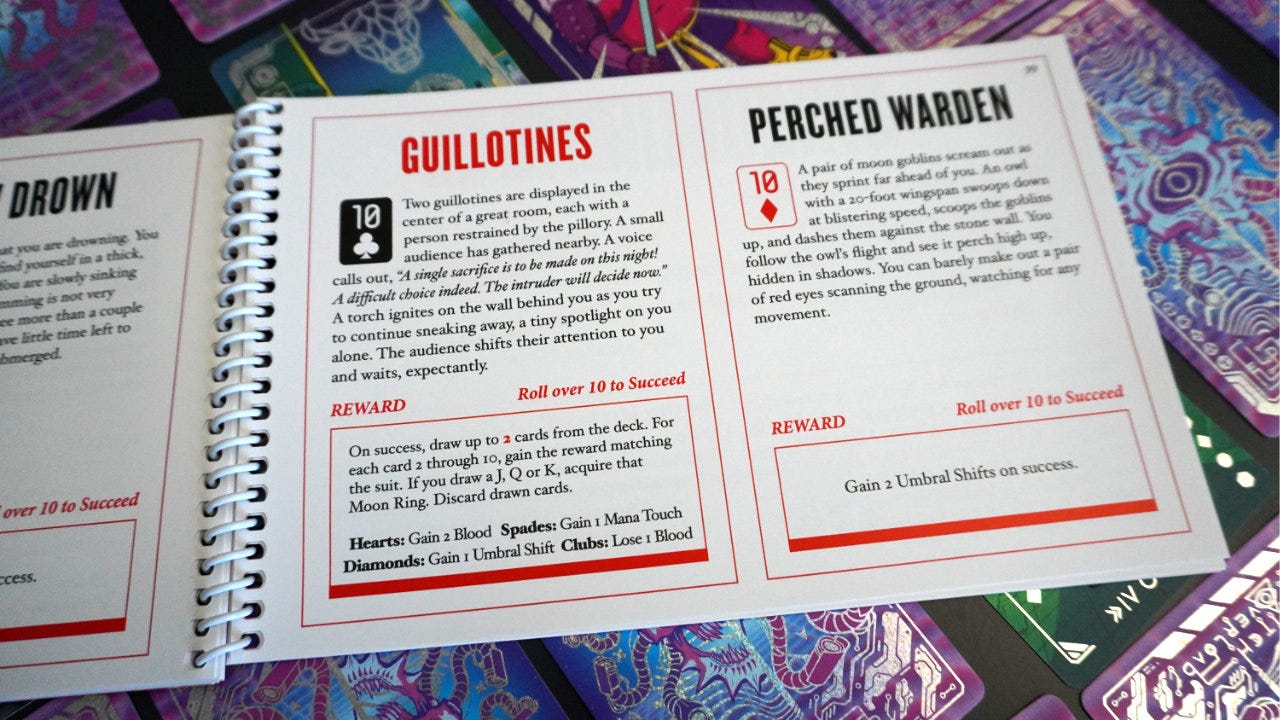

Encounter: Look up the card’s rank and suit for a journaling prompt and a target value for the dice roll based on the Aspire SRD.4

Journal: Record everything that happened and expand the story of your witch.

Let’s look at how Moon Rings takes the simple card-grid concept and turns it into an interesting narrative-focused game.

Twelve rings and five (or less) fingers

I plan to use Moon Rings as an example in future tabletop game design classes, showing what a card grid game could look like after the Nth iteration.

Which features would I point out? How does it take the simple card concept and turn it into a full game?

Here are four design features that immediately come to mind:

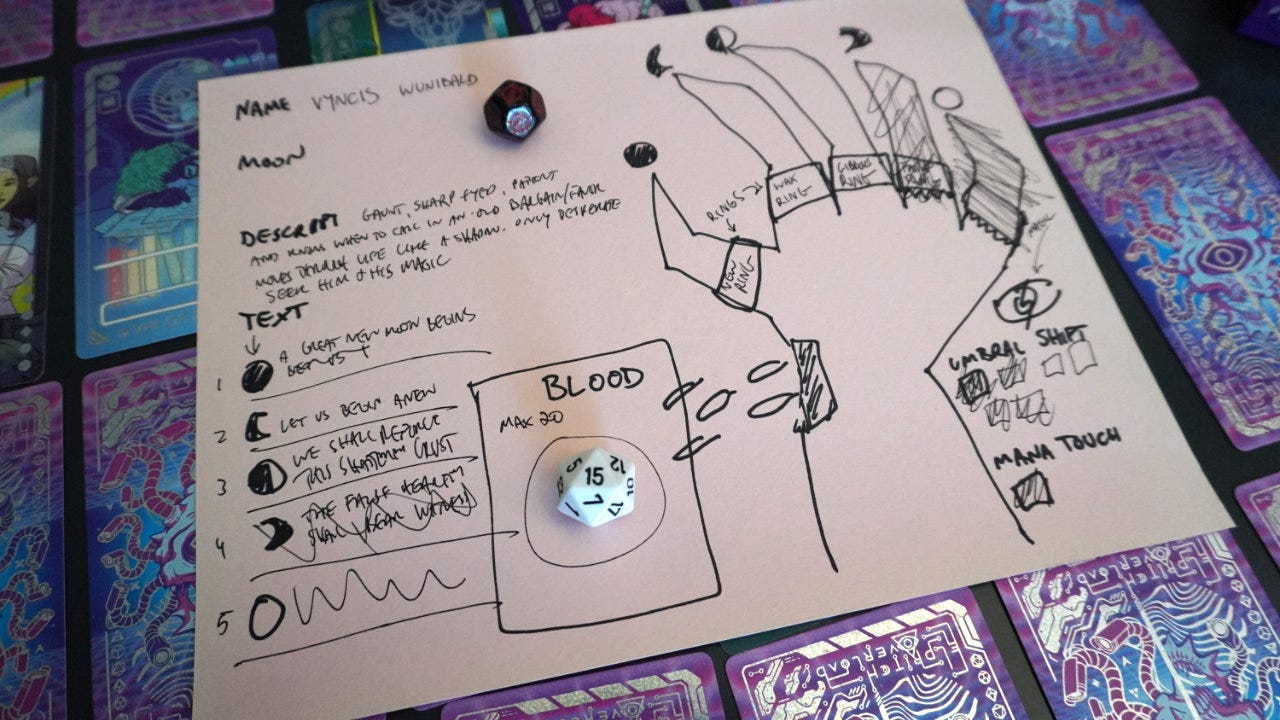

1. Give the player limited resources

Blood is the most obvious resource in the game. It’s your health and life. It starts at 20 and you die when it reaches zero.

Fingers are your other, perhaps less obvious, resource. You have five fingers available at the start of the game, one for each ring necessary to perform the ritual.5 These are more than just slots for rings when you find them, because they are not permanent. It is entirely possible for encounters to cost you a finger upon failure. In fact, I lost two fingers… one of which had a ring on it.6

Rings are the final resource because they too are not permanent. The game begins with an unknown number of them represented by face-down face cards (i.e. Jack, Queen, King) somewhere in the labyrinth’s grid. Failing the encounter with the ring removes it from the game.

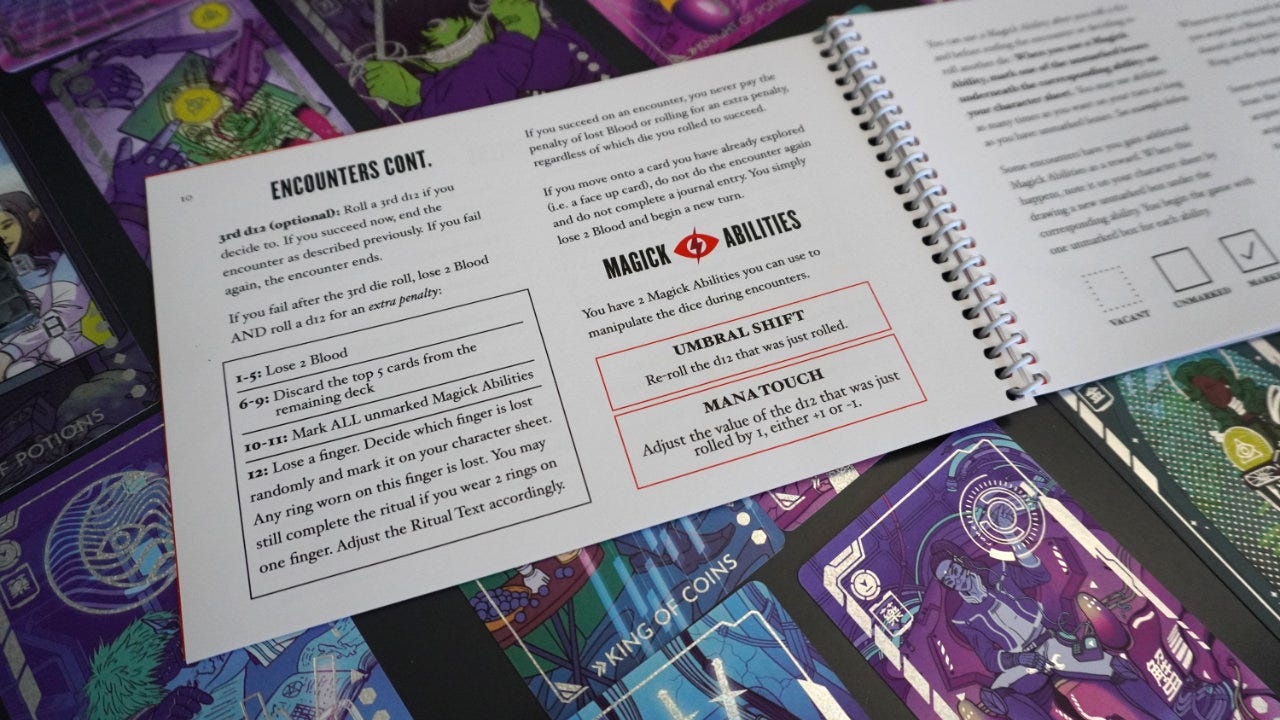

2. Force the player to push their luck

Encounters are simple in Moon Rings but add player agency to keep them mechanically interesting. Each one requires a d12 roll vs. a target number — beat the target and you succeed. There might be a benefit for succeeding like getting another spell slot or recovering some blood.

Failure is more tricky. On your first failed roll, you’ll lose 1 blood unless you push your luck with another d12 roll. Fail that one and now you’ll lose 2 blood unless you push your luck a third time. Fail that one and now you lose 2 blood and roll on an extra penalty table. Roll a 12 on that table (like I did twice) and you’ll lose a finger and any rings that happen to be on it.

It’s no secret that I love push-your-luck mechanisms, and this one is no exception. It coaxes you into giving it “just one more try” because the early penalties aren’t too bad. What’s so bad about losing 2 blood instead of 1? And then you might not even lose those 2 blood if you make your third roll. And if you fail that, maybe the extra penalty won’t be so bad.

Next thing you know, you have the hand of a particularly unskilled high school shop teacher.

3. But allow the player to mitigate their luck

As a witch, you have two Magick Abilities that can be used during the game to manipulate the dice: Umbral Shift and Mana Touch. With limited uses, these could be considered resources like blood or fingers.

In practice, they serve a very important role: luck mitigation.

Push-your-luck mechanisms are fun, but can easily veer into pure randomness. With no way to control or manipulate the dice, players can quickly lose interest. A few bad dice rolls and it’s not fun anymore. By giving players a way to mitigate a streak of bad luck, it maintains interest. The number of times they can mitigate bad luck is limited, adding player agency and meaningful choices in when to use the magic.

4. Let the player create a unique story

In a game that is relatively mechanically simple, it’s important to allow the player to create a compelling narrative.

Much like in Necromancer Heretic, the prompts are short but thematic. In just a few sentences, we are confronted with skeletons, creepy puppets, musical animals, blood slimes, and fake rings. Rather than focusing on detailed combat and complex resolution mechanisms, most are a simple d12 roll vs. a target number. Still, there’s enough narrative meat there to work with and create a story.

The arc of the game

Dwindling resources, desperate attempts to push your luck, and responding to the prompts combine to create a game arc in Moon Rings. Although the game loop is fixed (i.e. it’s the same Explore, Encounter, Journal each turn), it feels like the game has a beginning, middle, and end.

At the start, you are at full health (20 blood) and willing to take some chances while the entire labyrinth of cards is unknown. Pretty soon each point of blood matters a lot and using magic to mitigate bad rolls becomes important. Finally, it’s an end-game struggle to get that last ring and get back to the ritual site to stop the Blood Moon.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Card-based grids are a good entry point: I like that both new and experienced designers can find new ways to use a grid of cards to make a game. By using a standard poker or tarot deck, almost anyone can grab a PDF and give it a try. With custom components (cards, dice), designers can make really interesting games with this simple core system.

Subtle resources: It’s interesting that fingers (5 max) act as a decreasing resource in the game, but they are never explicitly explained that way. Instead it’s a thematic drawing of a hand. You scribble out each one as they are lost. In contrast, blood is explicitly shown as a resource (20 max). This is a concept I’d like to explore in a future article.

You don’t add a game arc: I’m increasingly convinced that a good game arc emerges from the interactions of the other mechanisms in a game. It’s not a mechanism itself that you just drop in. Sure, you could just say the game has X rounds and therefore it has a beginning, middle, and end, but that just wouldn’t be the same. It’s something that appears when the players interact with the systems.

What do you think? Did I capture what makes Blood Moon a good example of a fully-developed card-grid game? What other games would be good examples to use in future game design classes?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want more in-depth and playable Skeleton Code Machine content? Subscribe to Tumulus and get four quarterly, print-only issues packed with game design inspiration at 33% off list price. Limited back issues available. 🩻

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

If you want to attend a future game design workshop at a library, keep an eye on Exeunt Omnes. That’s where I share upcoming events like that.

You can hear more about this exercise in the How to Run a Tabletop Game Design Workshop at Your Library webinar I did for the Indiana State Library a few months ago. Skip ahead to the 34:30 timestamp to see it. Also, I mentioned it in the Hands-on Activities post at Exeunt Omnes.

Moon Rings uses a poker deck, so you’ll see me refer to aces, jacks, queens, and kings in this article. I decided I don’t use my fancy Eldritch Overload tarot deck enough, and used that instead. It’s only recently that I discovered you can use a tarot deck in place of a poker deck by removing the major arcana cards and one of the face card types. After that cups/potions = hearts, swords = spades, clubs = wands, and diamonds = coins. I removed the pages and used the knights as jacks.

Aspire is “a framework for designing narrative-driven TTRPGs featuring turning points that change both the stakes and the rules” created by S. Kaiya J. of Mirror-lock Atelier.

When I asked Chris (Moon Rings designer) why witches all seem to only have one hand, he said, “Gotta have the other hand free for other stuff, like eating and high fives.” And now this is how I want to live my life — one hand always at the ready for a high five.

You can put more than one ring on a single finger, so losing one doesn’t knock you out of the game.

I also have that tarot deck! So fun to look at. I also don't use it enough, but I have a million tarot decks. I also got the fancy custom deck for Moon Rings. Couldn't resist. Agree re: design and letting players create story and not forcing an arc.

I was thinking of a past article you wrote about player agency on a hexgrid map. One of the points you made in the article was the illusion of choice resulting from having no information about the contents of a hex tile (either face down or resulting from a randomized roll table of events). Do you think this game has a similiar issue?

My follow up thought was that you can give this game as an example of an Nth iteration to your students, but you could then ask the follow up question: What might an N+1 iteration look like? What are the pros and cons of this design decision?

To answer my own question, if the game contains the illusion of choice, I might consider adding an opening game mechanic where the player can reveal 1 or more cards before starting there opening move. I would have to know the game more to determine the right balance, but first pass would be something like roll the d12, low result reveal 1 inner tile lose 1-2 blood, roll 7-10 lose 3-4 blood reveal one inner and one outer tile, roll 11-12 lose 2 blood reveal 1 inner and 2 outer but on opposite sides. (Could do lose a finger at a certain tier, but I don’t know how impactful losing a finger is.) Cons: balance would need to be figured out, but may distract from the core game loop. Losing blood at the start may be a feel-bad. Not revealing a tile may also be a feel-bad. Pros: Players have agency from the first move and a possible plan of action (go towards or away from that tile).