Hunter vs. Hunted

Exploring hidden movement in Beast

With the 2023 ENNIE Award nominees announced, I was happy to see Broken Tales on the list for Best Adventure! We just looked at Broken Tales two weeks ago in the Upside Down Fairytales post! If you haven’t read that post yet, be sure to check it out.

This week we are back to board games, but with a mechanism that I’d love to see in a TTRPG: hidden movement!

We’ll use the Beast board game as the primary example!

Beast

In Beast (Midhall, et al., 2023), humans have begun to settle the forests of the Northern Expanse. This has caused great beasts from nature to push back with fangs, claws, and mystical powers. Hunters are now tasked with tracking down and killing the beasts.

This is a one vs. many game:

One player takes the role of the Beast, facing the others, who form a team of hunters. The Beast wins when a certain number of settlers are dead, while the hunters win either when the Beast is dead, or enough days (rounds) have passed and reinforcement arrives.

Throughout the game, the beast’s location is usually hidden, known only to the player controlling the beast. When the beast attacks a settler or animal, however, its location is revealed.

Because the beast can attack the hunters, this is less a game of cat and mouse and more akin to the original Predator (1987) film. The hunters can easily become the hunted!

For a comprehensive review of Beast, check out Shut Up & Sit Down’s Beast Review - Big Game Hunting.

But first let’s talk about hidden movement mechanisms!

Hidden movement

Hidden movement is exactly what it sounds like: Movement occurs that is not visible to all players.

In Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design, Geoff Engelstein uses the classic game Scotland Yard (Burggraf, et al., 1983) as an example of this mechanism.

Here’s the game’s description from BGG:

In Scotland Yard, one of the players takes on the role of Mr. X. His job is to move from point to point around the map of London taking taxis, buses or subways. The detectives – that is, the remaining players acting in concert – move around similarly in an effort to move into the same space as Mr. X. But while the criminal's mode of transportation is nearly always known, his exact location is only known intermittently throughout the game.

Scotland Yard demonstrates some common elements of hidden movement games:

One side or one player secretly moves on a map

The overall map is known and/or visible to both players

The hidden side keeps a log or record of movement

Multiple hunters seek a single target

The target periodically reveals their location

While these elements are just examples and not required, they do show up in Beast.

So let’s explore Beast in more detail!

Hunting the beast

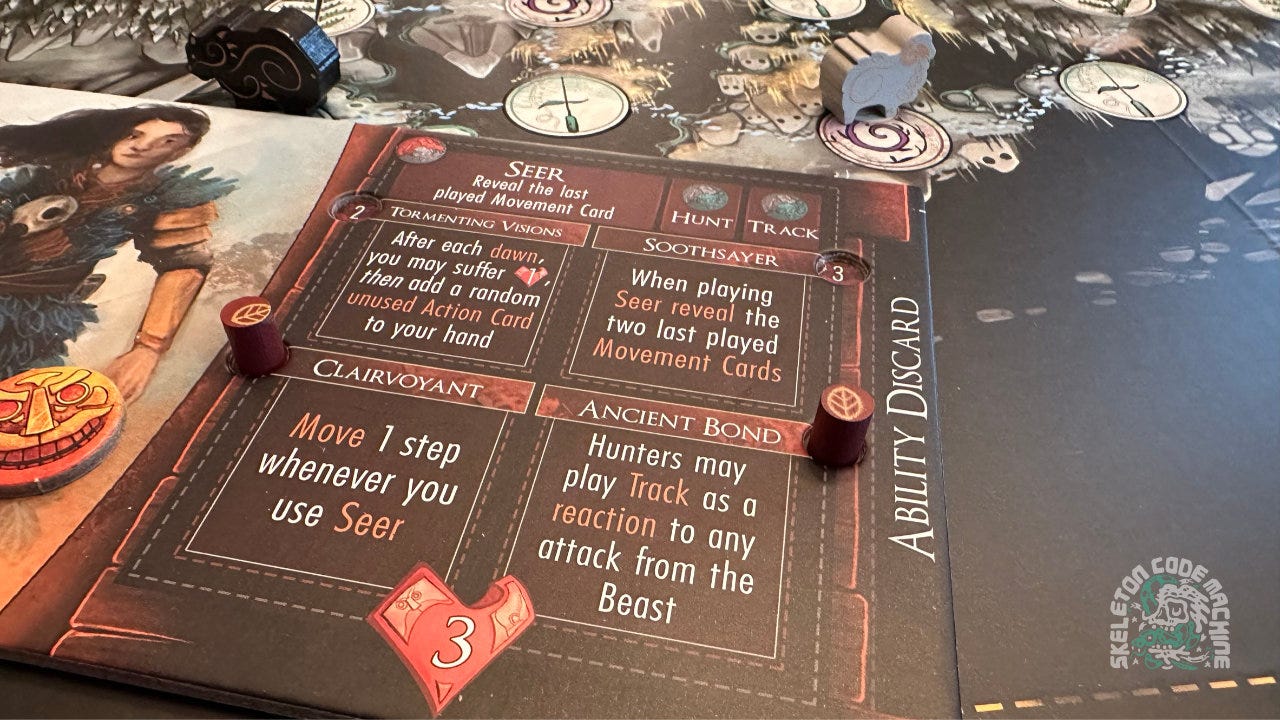

Each day begins with drafting action cards, followed by taking those actions (e.g. moving, tracking, hunting, attacking). Each night the players check for rewards, restore health, and upgrade their beast or hunter abilities.

The board is a point-to-point map of habitat types (e.g. forest, swamp, cave, settlement) connected by paths. The hunter positions are always visible on the map, as are the various types of targets for the beast (e.g. sheep or boars).

As the beast moves, they place face-down movement cards (i.e. North, South, East West) and secretly track their location on a mini version of the map hidden behind a player screen.

There are three particularly interesting things Beast does related to hidden movement:

Knowledge of possible actions: Each card has both a hunter and a beast action on it, so it’s the same pool of cards for both sides being drafted. During the draft, everyone gets to see the cards that will be used for that round, giving an idea of how much movement is available. This encourages tactical “hate drafting” to deny your opponent valuable cards.

Temporary tracks left behind: As the beast moves, it leaves tracks as recorded by the movement cards. If a hunter ever moves to a space in the current set of tracks, the beast must reveal this with a token. This allows the hunters to know where the beast has recently been.

Frequently revealed location: The scenarios are short, so the beast is pressured to act aggressively to win. This forces them to reveal their location frequently, resetting the movement cards, and their trail never gets too long.

It’s notable that the rules say the mini map is optional. Perhaps because the beast is revealed frequently (almost every day), the tracks are short, and most people could maintain a mental map of both the beast’s current/previous locations. I know I’d have a hard time remembering all that! For what it’s worth, I’d only play with the mini map.

Other examples

Hidden movement has been around a long time, especially in wargames such as Bismarck (Roberts & Shaw, 1962).

If you are designing a hidden movement game, I’d recommend playing (or at least reading the rulebooks for) the following:

Specter Ops (Matsuuchi, 2015)

Fury of Dracula (Brooks, et al., 2015)

War of the Ring: Second Edition (Di Meglio, et al., 2011)

Mind MGMT (Cormier & Lim, 2021)

Letters from Whitechapel (Mari & Santopietro, 2011)

Sniper Elite: The Board Game (Tankersley & Thompson, 2022)

Design challenges

BGG calls out some significant hidden movement design challenges:

A key challenge for designers is determining how to make the movement rules simple enough that the players moving hidden units do not make mistakes, or that paths are traceable when the game concludes.

Let’s look at both of those concerns:

Hidden player mistakes: In asymmetric games, catching mistakes is harder because players may not know everyone else’s ruleset. In hidden movement games, the actions themselves are hidden. Combine that with a one vs. many game, and there is a lot of pressure on the single person being hunted to get everything correct!

Traceable paths: This should be implemented in a way that reduces the burden on the hunted player. In Beast, movement cards are placed on the board in order as they are played, revealed only when an attack occurs. In Sniper Elite: The Board Game (Tankersley & Thompson, 2022) the sniper tracks movements on a hidden board, noting the current number of the countdown track so the path can be discussed after the game.

Ultimately both concerns are related to the risk of the hidden player making a mistake, only to realize this at the end of the game. This would lead to an extremely unsatisfying end to the game.

The longer the hidden player remains hidden, the more room there is for error.

Design choices that can help mitigate these risks include: (1) forcing the player to periodically reveal their location, (2) having clear rules, and (3) keeping a simple audit trail for the hidden player.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Hidden movement mechanisms present specific design challenges. As noted above, the rulebook needs to be exceptionally good and play errors can ruin the game.

Hidden movement games might require more components. Not always, but many times you’ll want a small version of the map, a way to log movements, and other items not required in other settings. While this isn’t an issue with many board games, it could be tricky with a print and play release.

One vs. many and hidden movement mechanisms could be an interesting twist in TTRPGs. I’m not speaking about an “adversarial DM/GM” but rather a game where there are hunters and the hunted, either with or without a referee. Perhaps two teams plus a GM?

What are your favorite hidden movement games? What are some other ways to reduce errors during the game? Have you played any TTRPGs with hidden movement elements? Let me know in the comments below!

The best way to support Skeleton Code Machine is to share it with a friend!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

See you next week!

— E.P. 💀

What do you know? I’ve been working my way through hidden movement as a mechanic after reading and becoming obsessed with Striker that simulates fog of war using spotting rules either with a referee or by using counters to represent possible locations for unrevealed units.

I actually have a crowd sale going right now for a double-blind Microgame, Thrust!, inspired by the upcoming Mothership ship combat rules, Battleship, and the old GDW double-blind games.

https://thrust.rvgames.company

Those old GDW double-blind games are fascinating, only their Market Garden game is really successful with the way you are able to drop paratroopers into enemy territory.

I’m also working on an asymmetric single-blind game, Left at Home, that takes the form of a board game inspired by Enchanted Forest, Mothership Panic Engine, and PbtA playbook hybrid. The theme and art for this one are turning out great for this one too: Home Alone + Evil Dead. I even figured out how to have a solid solo mode in a hidden movement game, which is difficult.

Finally, part of my in-development Mothership module, Orgy of the Blood Leeches, will include hidden movement for encounters (controlled by the Warden), all of my smaller designs are and have been practice for completing this module.

Great write up, EP! Lots of good stuff to think about and look into. I like the idea that the hidden player needs to expose their location from time to time, and they need to be under pressure to force them to take those risks.