What makes a dungeon crawl good?

Exploring the common elements of dungeon crawl games and how to make them better

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, an ENNIE-nominated and award-winning weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Check out Public Domain Art and Fragile Games to get started. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration delivered to your door each quarter!

Last week we explored the idea of a game arc and how it helps us understand change in tabletop games. I reference that article a few times in this one, so check it out if you missed it.

This week we are lighting torches, going down stairs, and seeing what makes dungeon crawls one of the most enduring genres in gaming.

The dungeon crawl

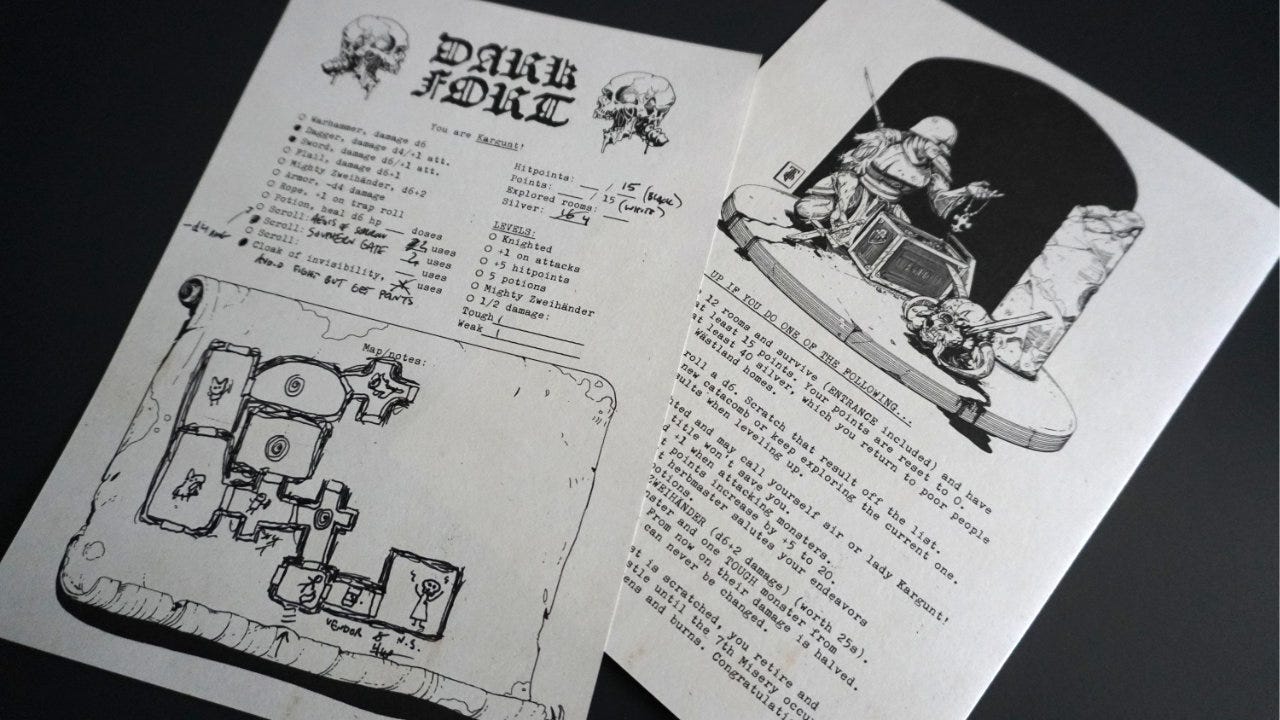

Last year I wrote about thematic design and simulating combat in Dark Fort, the four-page predecessor of what would become MÖRK BORG.1 What I found interesting about Dark Fort was how it distills the essence of the genre into such a small space — explore, fight, loot. And yet it manages to do this in a highly thematic way by focusing on the first two layers of thematic design.

Dark Fort is a perfect example of a dungeon crawl — a game where players explore an area, encounter enemies, and collect loot. This genre exists in tabletop board games (e.g. Gloomhaven, Massive Darkness 2: Hellscape, Cthulhu: Death May Die), tabletop roleplaying games (e.g. old-school Dungeons & Dragons, Dungeon Crawl Classics), and video games (e.g. Diablo).

Since writing the Dark Fort articles, I’ve had some ideas for a hack of Dark Fort. The trick is to keep the same tight design, but to also make it feel like my own — original and new.

So let’s explore the core elements of a dungeon crawler game, and then come up with some design tips to focus on when making a new one.

Common elements of dungeon crawlers

As with almost anything, strict definitions aren’t particularly helpful when exploring ideas for game design. It was hard enough to define a mech, so we know there will be exceptions to any definition.2 Similarly, it’s impossible to list every common element.

There are a number of elements that seem to usually show up in some of the most popular games that are widely considered to be dungeon crawlers:

1. Character progression

Character progression is often explicit “leveling” where your character begins at Level 1 and increases to Level 30 or beyond. In classic D&D and video games like Diablo, this is achieved by accumulating experience points (XP).3

Even dungeon crawlers without much story arc (e.g. Dark Fort) still are enhanced by having a solid game arc — organizing the changes during the game into a beginning, middle, and end. Few want games that feel exactly the same at the start all the way through to the end.

2. Combat encounters

Not every dungeon crawler has combat, but most do. Kicking down the door and fighting the monsters inside is a core trope of the genre. Why were they just sitting in that room waiting for you? Who knows? I’m attacking with +3 to hit.

Games need obstacles for players to overcome — some barrier between the start and the goal. Combat is an easy and (usually) interesting way to achieve this. Even in storytelling TTRPGs, combat often switches to turn-based encounters resembling a board game or miniatures wargame.

3. Loot, equipment, and rewards

If combat is the primary obstacle for players to overcome, there needs to be a reward for overcoming it. That’s where loot, upgraded equipment, and other rewards comes in to play. Gaining better weapons, armor, and XP is an obvious and important way to give a sense of character progression, as noted above.

4. Puzzles and environmental challenges

Harder to design, but potentially more satisfying are puzzles and environmental (e.g. walls, water, fire, pits, etc.) challenges. Along with combat encounters, these act as obstacles for the players to overcome. Solving the puzzles leads to more loot and rewards being handed out and allowing for more character progression.

I’d also include traps in this category, as I feel that the best dungeon traps are puzzles to be solved. It’s not much fun to open the door and get killed.4

5. Randomization and replayability

The dungeon itself doesn’t need to be randomly or procedurally generated (though many are), but random encounters are a common element of dungeon crawlers. This can be handled via random tables, a deck of cards, or other dice roll mechanisms. No two playthroughs are identical.

Dark Fort has a fully random dungeon — rooms and their contents are all dice rolls. This makes it infinitely replayable, but at the cost of coherent narrative. Games like Cthulhu: Death May Die and Massive Darkness 2 use pre-defined scenarios with random events and encounters, allowing for more narrative cohesion.

Designing a good dungeon crawl

If those are the common elements of dungeon crawlers, we could build those into a game and call it a dungeon crawler. That’s fine, but would it be a good dungeon crawler? That’s a different question.

Depending on the kinds of fun you want to have with your dungeon crawl, here are three things I would focus on:

1. Exploration and discovery

Make sure the game creates a sense of surprise and wonder.

To me, this is the “magic” that makes good dungeon crawls great. Wondering what is down the hallway. Kicking down doors to see what’s inside. Getting surprised by an unexpected trap or monster. Discovering secret doors and weird ways to overcome obstacles. Not all dungeon crawlers create this sense of exploration and discovery, but the best ones do.

Because it is easier to accomplish this in a TTRPG with a GM running the game than in a fixed-scenario board game, TTRPGs usually have an edge in this area. Still, it is worth considering how to add more surprise and unexpected discoveries into your dungeon crawler.

2. Risk, player agency, and meaningful choices

Create a world with risks and where failure is a very real possibility.

As noted above, obstacles (combat, traps, etc.) are a core element of most dungeon crawlers. If they are trivial to overcome, they stop being obstacles and the game quickly becomes boring. It is the risk of failure and defeat that makes the players choices meaningful.

I’d recommend reviewing the CCI model of player agency — choice, control, and influence. While not perfect, the model is a good way to test a game to ensure that the players have real choices and not “false choices.”

3. Engaging progression system

Keep players engaged with a feeling of growth and increasing power.

Epic loot, XP, and unlocking skill trees are all ways to accomplish this. There is a reason that most video games use these methods — they work. There are other ways to give a sense of progression without an explicit experience point system.

Cthulhu: Death May Die doesn’t use explicit XP and instead each character has a sanity tracker. Whenever you lose sanity, your tracker advances to the right periodically crossing milestones that allow you to gain extra dice and level up skills. If the sanity track ever reaches the skull at the end, however, the player is “consumed by madness” and eliminated from the game. It’s a highly engaging twist on progression combined with push-your-luck.

Dungeon crawl board games vs. TTRPGs

You may have noticed that I don’t have separate lists for board game design vs. TTRPG design. That is on purpose. Regular readers of Skeleton Code Machine will know that I appreciate the blurry divisions between board games and TTRPGs, feeling that good design tips apply to both.

Board games will have more of a focus on mechanisms, have more structure, and probably include win/loss conditions. TTRPGs will probably have a richer narrative, better story arc, and perhaps less of a focus on mechanisms. Both, however, would do well to create a sense of exploration and discovery, give players agency, and have a sense of progression.

As with most tabletop gaming advice, it depends on what kinds of fun you want your players to have and what player promises your game makes.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Dungeon crawlers are everywhere: The dungeon crawl genre exists in board games, TTRPGs, and video games. It appears to be endlessly popular and has remained that way for decades. You could do worse than trying your hand at making a dungeon crawler.

The Platonic ideal dungeon crawl: My goal was not to strictly define “dungeon crawler” games, but to list some common elements. I’m not sure about you, but these lists (and the process of making them) are really helpful when designing a similar game. Knowing the conventions allows you to know when to break them. Can I make a dungeon crawl without combat? Can I make a progression system without levels? What if there were no physical loot?

Common recommendations: It’s notable the three recommendations for making a good dungeon crawler can be applied to almost any game. Almost every game is made better by adding a sense of discovery, making choices matter, and creating a game arc. Not every game needs these things, but they sure do seem to help.

What do you think? What makes your favorite dungeon crawler different from the others? Which dungeon crawler elements are the most important?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Subscribe to TUMULUS, a Skeleton Code Machine quarterly, to get four issues of creative game design fuel delivered to you. Issue 1 is shipping now through the end of February 2025. I appreciate your support!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

MÖRK BORG (“dark castle” in Swedish) is a dark fantasy tabletop roleplaying game by Pelle Nilsson and Johan Nohr, published by Free League. It has a very generous third-party license which makes it easy to make content Compatible with MÖRK BORG.

Did I claim you can’t define a mech, and then go on to write 1600+ words on the definition of a mech? Perhaps. I contain multitudes.

These are simply called points in Dark Fort. Gain 15 points and you level up.

TTRPG designer M. Allen Hall has an article on this topic in the upcoming TUMULUS Issue 2 set to be published in March 2025. Subscribe to read it!

Very interesting read! I love me some good old dungeon crawling. I voted Randomization & replayability, although both in the article and poll for dungeon crawling, ''dungeon design'' isn't mentioned, oddly. But I guess Randomization & replayability sort of covers that. Keep up the good work!