How to use D66 random tables

Exploring dice, probability, and how to get 36 options for your next oracle

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, an ENNIE-nominated and award-winning weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Check out Public Domain Art and Fragile Games to get started. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration delivered to your door each quarter!

Some important updates:

📝 Did you take the Skeleton Code Machine Annual Reader Survey yet? Takes just a few minutes! Closes tonight!

🗳️ Did you submit your picks for The Bloggies? The Bloggies were “celebrate standout TTRPG blog posts from the past year.” Today is the last day!

📦 Become a TUMULUS Founder: There are still some founder subscriptions available. Hurry up to get all the extras!

Now onto… D66 tables!

Ask the oracle

I’ve been going through some of the games I picked up at PAX Unplugged, such as TORQ which we explored last week in Stunts, Horsepower, and Driving Off the Map. This week I read through Blueberry Wine, a “solo horror hex-crawl” by Quinn Blackwell.

In Blueberry Wine, you live in the Sinking Fen — a land cursed by murdered witches and sinking into the watery earth. The game is based on Trophy Dark and uses many of the same mechanisms, but adapts the system into a solo game. Without a GM, this requires some other method for the player to determine what happens next, to generate random events, and to populate the world. This is done using an oracle.

In solo TTRPGs, an oracle fills in the gap left by the removal of a GM. Using dice, cards, or other methods, the oracle is used to answer questions, provide prompts, and generate outcomes.1 It can be as simple as rolling 1d6 to answer a yes/no question:

Yes

Yes, and…

Yes, but…

No

No, and…

No, but…

The addition of open-endedness to some of the results (e.g. “Yes, but…”) allows space for the player to add interesting twists and turns to the narrative. Is there treasure in box? Yes, but… there is also a spring-needle trap.

In other cases, the oracle may need to determine something more complex than a simple answer to a player’s question. What type of item do I find? What kind of monster is behind the door? What is the name of the next location in the quest?

All of these questions require a larger list than just six items and using a single d6.

Probability of 1d6 vs. 2d6

If six random options aren’t enough, you might be inclined to just add another six options. Instead of rolling 1d6 (1-6), the player can roll 2d6 (2-12) and get 11 options. Rolling 3d6 (3-18) would give 16 options. The issue is that the probability distributions of rolling 1d6, 2d6, and 3d6 are not the same!

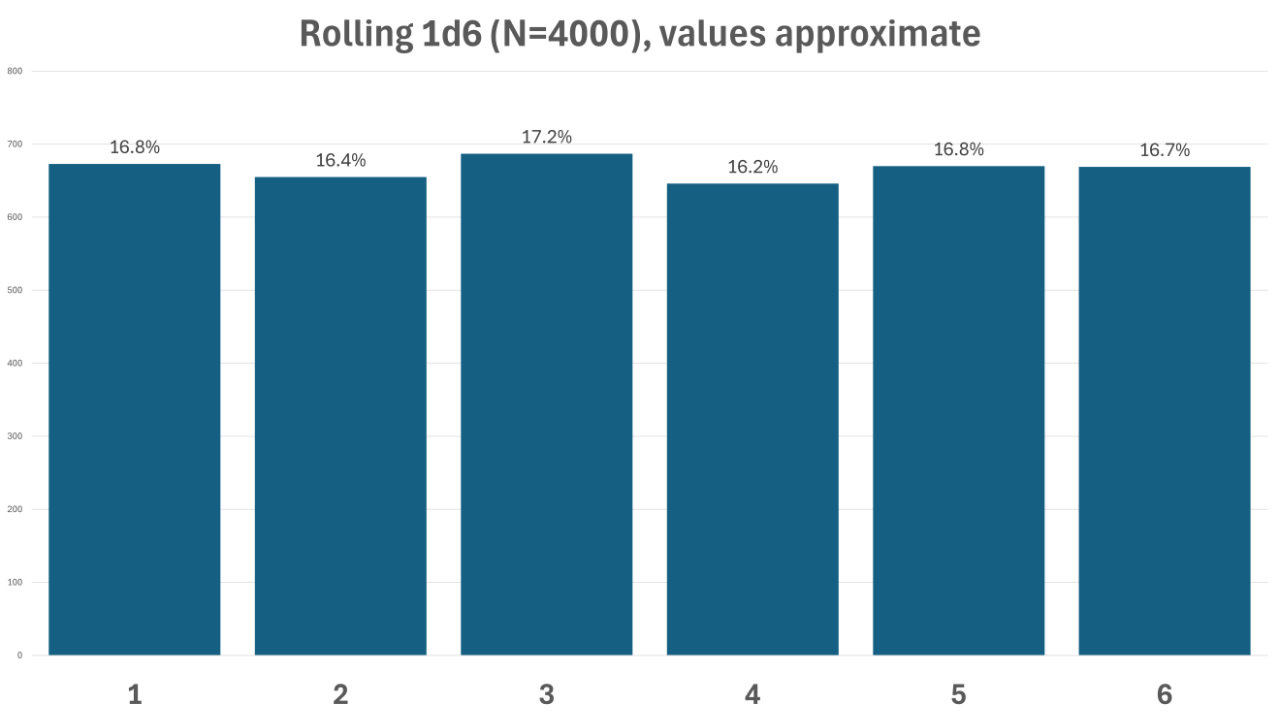

If you roll 1d6, you will get a result between 1 and 6. The chance of getting any one value is always 1 in 6 or 16.67%. For example, using the yes/no table above, there is an equal probability of getting Yes as there is No or any other option.

When you roll 2d6 and add the results, you will get a result between 2 and 12. There are more values, but they are not all equally likely to be rolled. There is less than a 3% chance that a 2 (1+1) or 12 (6+6) will be rolled, while rolling a 7 has an almost 17% chance. It’s not the “bell curve” of a normal distribution — rather a pyramid or triangle shaped distribution.2

Using 3d6 dice starts to flatten this pyramid shape a little, making it look a bit more like a normally distributed bell curve. There’s less than a 0.5% chance of rolling a 3 or 18. Rolling between 8 - 13 is far more likely.

As a designer, there are times you want some results to come up more than others. Many times, however, you don’t want the player getting the same result time after time. So a “flat” distribution like the one provided by 1d6 is desirable, but it would be nice to have one with more than six options.

Certainly you could use a die with more faces — d8, d10, d12, d20. That method works, but you hit a maximum of 20 options assuming you are using standard polyhedral dice.

The D66 table

One way to get a flat probability distribution and more options is to use a D66 table — a type of table that’s commonly used in TTRPGs. Here’s how it works:

Two dice are rolled, preferably each a different color.

One die represents the first digit of a two-digit number, and the other die represents the other digit of a two-digit number.

This two digit number is referenced against a table with options from 11 to 66, for a total of 36 options.

For example, I roll 2d6 and get 3 and 4 as the two results. That yields 34 as the result, which I can then look up on the D66 table.3

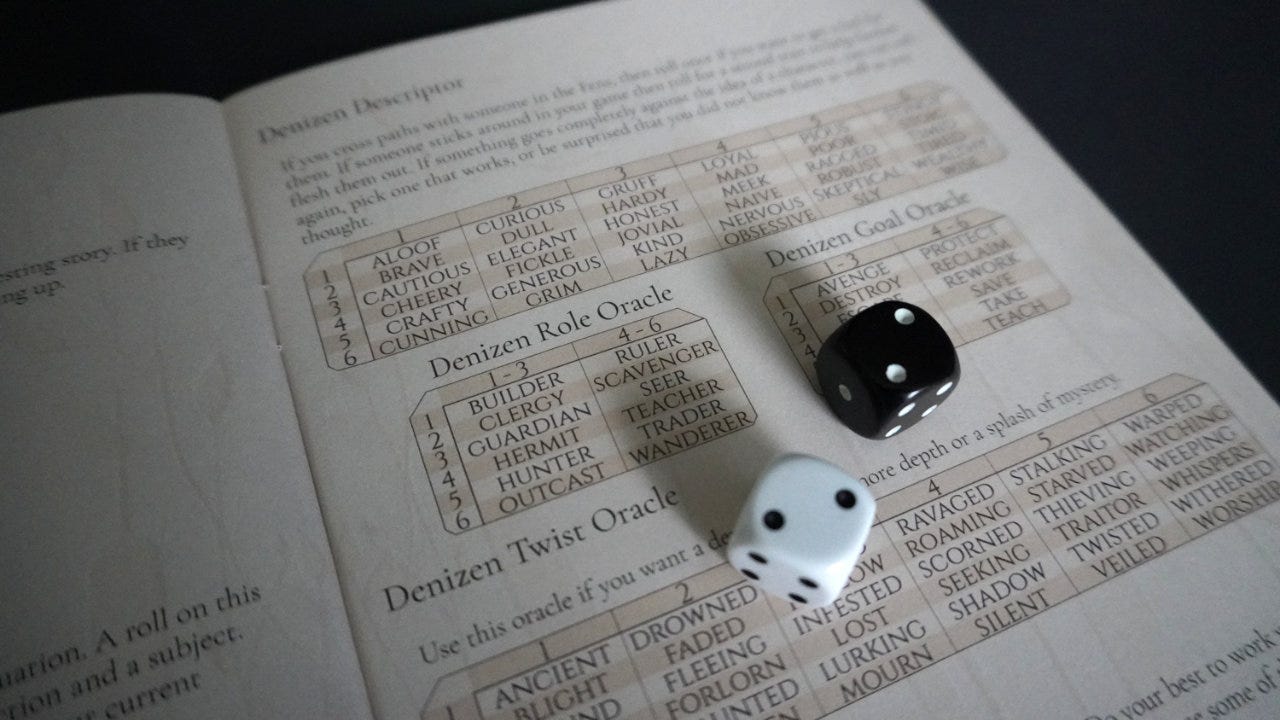

Blueberry Wine uses many D66 tables in the Oracles section, each displayed as a 6x6 table of options. The Monster Feature Oracle includes words like barbs, gills, shell, and wings. The Action Oracle includes clash, create, hunt, and inspect in its 36 options.

Modifying the D66 table

The D66 table format can be modified to allow for different numbers of options rather than just 36. One way to do this is to group the results of one die.

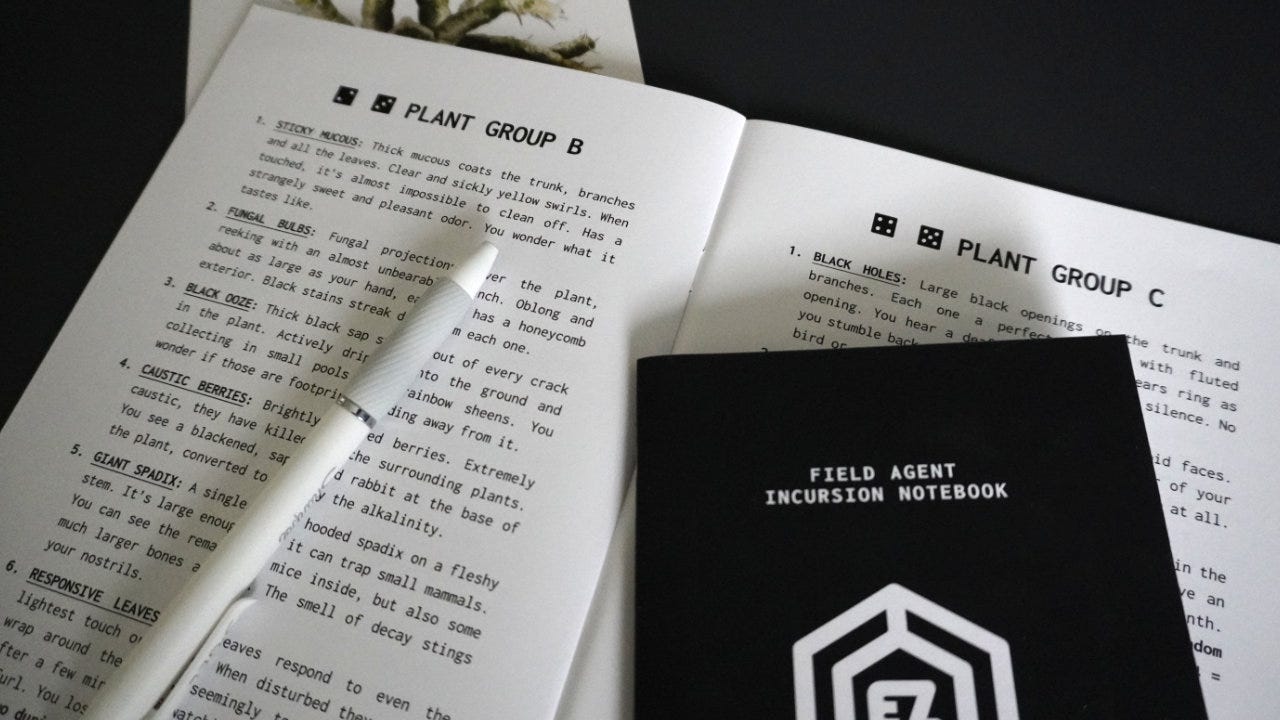

I used this method in Exclusion Zone Botanist when discovering new plants. Two dice are rolled — one light and one dark. The dark die determines the plant group (e.g. 1 = Group A, 2 or 3 = Group B, etc.) and the light die determines the plant feature within that group. With four plant groups (A…D) and six options in each group, this yields a total of 24 options. Group A and Group D are intentionally designed to be less likely to appear because they specifically require a 1 or 6 to be rolled, while Groups B and C have two values each.

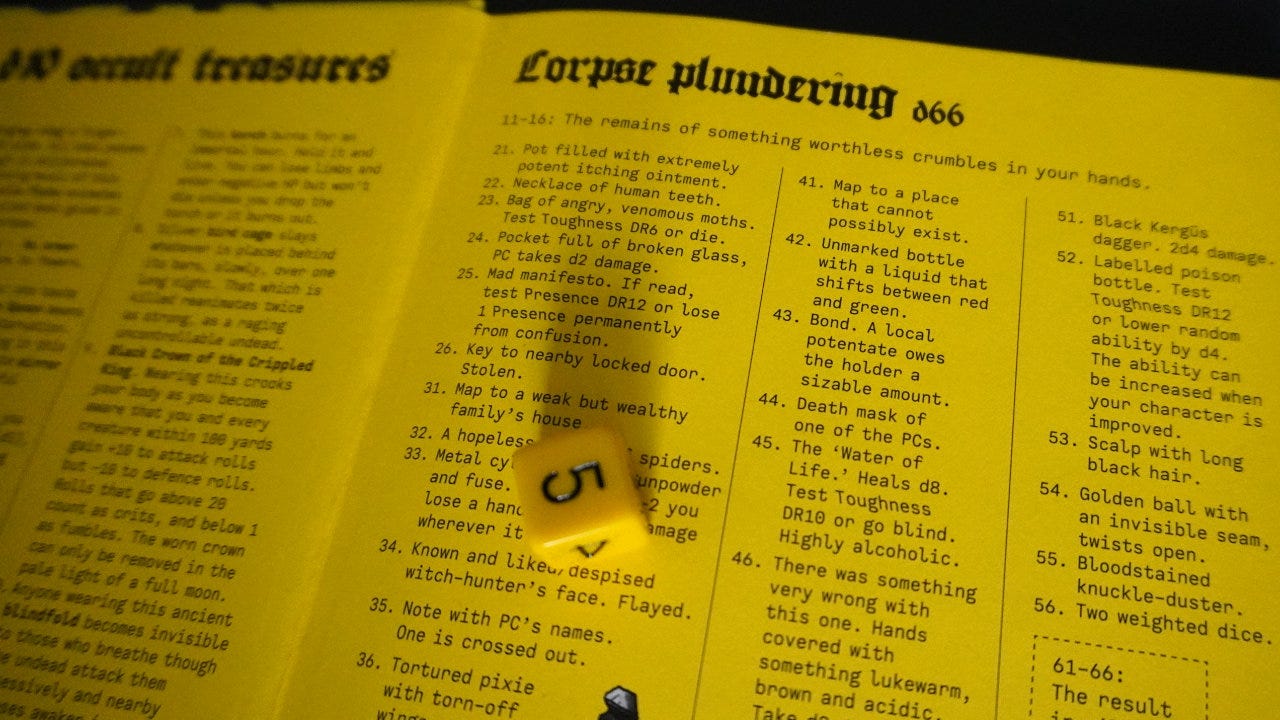

MÖRK BORG has a D66 Corpse Plundering table at the front of the core rulebook. Instead of having 36 options, the first 11-16 results are simply, “The remains of something worthless crumbles in your hands.” The remaining 21-56 options contain loot of questionable value (e.g. “32. A hopeless amount of spiders.”), while 61-66 give that amount in silver.

Trophy Gold book uses a modified D66 table for omens (photo above). A dark and light die are rolled, but the dark die results are grouped in the table. A dark die result of 1, 2, or 3 uses one list while a result of 4, 5, 6 is the other list. This give a flat probability distribution with 12 (2x6) options (including “Cannibal Crows” and “Heartless Hog”).

Another common modification is to use a D666 table, using each of 3d6 as a place in a three-digit number. Rolling a 3, 4, and 5 would yield 345 which can be looked up on the table. The table values range from 111 to 666, with 216 unique options.

Using different dice for D66 tables

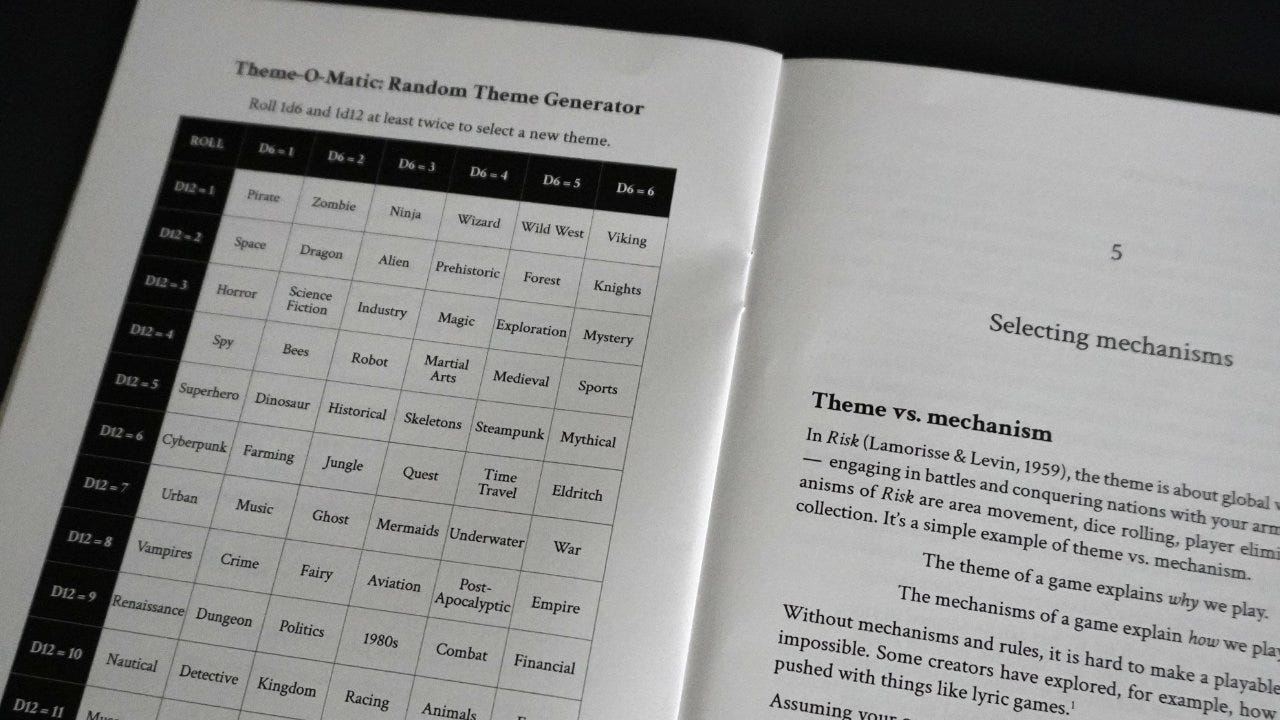

You don’t need to limit yourself to d6 dice when making D66-style tables. In the Make Your Own One-Page Roleplaying Game (pdf) book, I include a Theme-O-Matic: Random Theme Generator. It uses a d6 and a d12 for the dice, yielding 72 (6x12) options in a way that easily fits on an A5-sized page.

Modifying the dice used increases the flexibility of D66-style tables so that you can make one to fit almost any need or number of options. A D88 table would be 64 options. Rolling 2d12 would give you 144 options! Dare you use the 2d20 table of 400 options?

Of course, even more options are available if using specialized dice (vs. d6) such as d10s, percentile dice, and d100s.

How to present D66 tables

How a D66 table is displayed can have a large impact on how easy they are for the player(s) to use. Two methods are common:

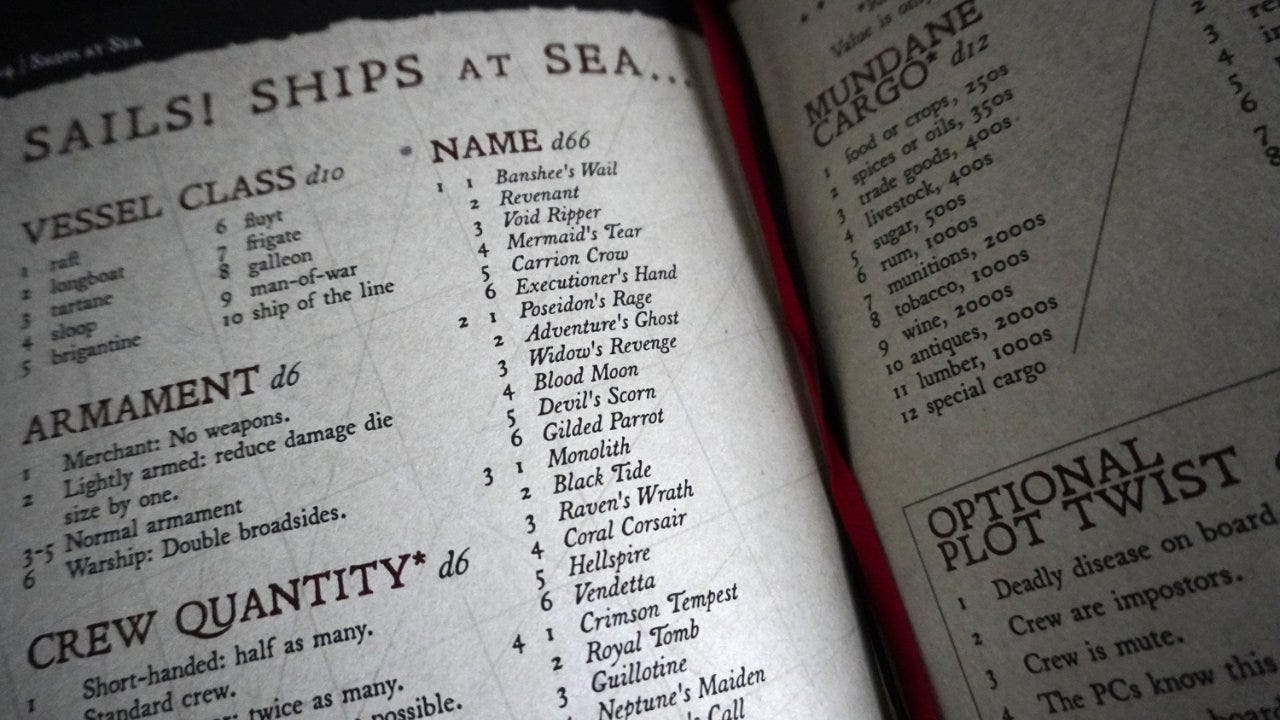

Single, numbered list: This is just a numbered list. The difference is that because the digits are only 1-6, the list goes from 11 to 66. The sequence goes 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 31, and so on.

Grouped, numbered lists: Rather than printing the first digit six times as in the numbered list, the options are grouped. There are six groups with clear headings or other indicator, and then six options within each one. See the Pirate Borg example photo above.

Some show the dice results as actual dice symbols, as done in the Trophy books.4 Others simply use the numbers.

Using D66 tables in board games

While D66 tables are fairly common in indie TTRPGs, it is uncommon to see D66 tables used in board games. Why is that?

D66 tables can be hard to explain: In my experience, new players can be confused by D66 tables. Their natural instinct is to add the dice rather than use them as individual digits in a single number. It can also seem odd that the list begins at 11 and skips from 16 to 21. Certainly, a good rulebook overcomes this issue, but it can be a reason to avoid D66 tables.

D66 tables can be tough to display: Visual and graphic design of D66 tables is important to their usability. For text-only, options range from the 6x6 table of Blueberry Wine to the header-and-list of Exclusion Zone Botanist. If you want to add images and graphical elements to the table results, it becomes even more complex.

Custom components are easier: While indie TTRPGs often try to put all the rules in a book and have the user bring their own dice and paper, board games often provide everything needed in the box. This means they can just as easily provide a deck of cards (e.g. 52 options) which is easier and faster to use than a D66 table.

I can’t think of any board games that use D66-style tables, probably for the reasons above. If you are aware of any, please let me know in the comments.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Not all dice probabilities are the same: Many new designers are unaware that 1d6, 2d6, and 3d6 probability distributions are all different. Each has it’s own distribution, and knowing the difference is important when designing a system.

D66 tables are handy: If you need more than six random options and want a flat probability distribution, D66 tables can work for you. The basic design has 36 (6x6) options, but they can be modified using grouping or different dice.

Custom components usually are better: While D66 tables are useful and work well in indie TTRPG design, if you are using custom components (e.g. cards, dice, boards, etc.) there are often easier and faster ways to generate random results. Cards have the advantage of having a “memory” and storing more information.

D66 tables seem pervasive in the TTRPG world, but not nearly as much outside of that. I’m curious if this article introduced you to the concept or if you were already aware of how they worked!

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Did you take the Skeleton Code Machine Annual Reader Survey yet?

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

The Dark Fortress has a nice chart and discussion of 2D6 Score Probabilities. There’s also a page showing 3D6 Score Probabilities.

Note that D66 results start at 11 and go to 66. There are no 7, 8, 9, or 0 digits. When listing the options it would go 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 22, 23, and so on.

I love how the Trophy Dark and Trophy Gold books look and I think using dice symbols works extremely well in the design. I’ve seen some discussion of which is “better” for usability — numbers or dice symbols. I’m not really sure it makes much difference.

"D66 tables can be hard to explain"

Isn't it mostly a naming issue? (since there is no "D66" in the same sense as there are "D12s" or "D100s" *)

If we just call them "tables" and explain "roll one six-sided dice for the column, another for the row", there isn't much room for confusion, no?

* Well, except with a sleigh of hand, switching from base-10 to base-6, which is indeed confusing for non-math-people ...

In case you haven’t run into it, anydice.com is fantastic for quickly seeing the distribution, or even cumulative probability, of different dice combos. The cumulative readout is really handy for roll-under systems; it can also cumulate the other way (% rolled above N) to simplify analyzing roll-over systems without getting clever with the custom programming language it supports.