Layers of theme in tabletop games

Exploring Sarah Shipp’s Three Layers of Theme

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Last week we concluded the three-part series on the three-player problem and kingmaking.

This week we explore the use of theme vs. mechanisms in games, a topic we’ve looked at before in the context of Tangled Blessings and Inhuman Conditions.

Specifically, we will be looking at a model proposed by Sarah Shipp in Thematic Integration in Board Game Design (CRC Press, 2024), a book I recently mentioned at Exeunt Omnes.

Theme vs. Mechanism

In MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research (Hunicke, LeBlanc, et al.), a game’s mechanics are defined as:

Mechanics are the various actions, behaviors and control mechanisms afforded to the player within a game context. Together with the game’s content (levels, assets, and so on) the mechanics support overall gameplay dynamics.

Mechanics (a.k.a. mechanisms) define how the player interacts with the game and what decisions they can make. Examples might include turn order, action selection, or dice rolling.

Theme, on the other hand, is a bit harder to define. It can be the setting, story, or narrative context of the game, including the elements that give the game “flavor” or atmosphere.

In Thematic Integration in Board Game Design, Sarah Shipp says:

Theme encompasses the setting, story, and tone or mood of a game. It is expressed via illustration, components, mechanisms, and narrative descriptions.

A game might have no theme, in which case we’d call it themeless or abstract, with Tic-Tac-Toe and Go as good examples. It is hard to imagine, however, a game without mechanisms.

Pasted on themes vs. thematic games

A game’s theme can feel “pasted on” when the theme has minimal connections to the actual gameplay.

This isn’t always a bad thing, however, as shown by games like Azul (Kiesling, 2017). While Azul’s theme is only loosely connected to the mechanisms, it’s a gorgeous game that gains much from the beautiful tile-laying theme.

In other cases, a game might be a mix of strong thematic connections and weaker ones. Blood Rage (Lang, 2015) has thematic miniatures that are moved around on a map to trigger combat, and yet also includes a rather abstract card drafting phase.

The opposite of a “pasted on” theme is a “thematic game.” These are games where the theme is deeply integrated into almost every aspect of the game. The mechanics reinforce the theme. The components help support player immersion. Roleplaying is encouraged and comes naturally, sometimes causing players to make suboptimal choices.

It’s no surprise that the top ranked, most thematic games on BGG are the ones that start to blur the line between board games and roleplaying games. The top 15 thematic games include: Pandemic Legacy: Season 1 (2015), Gloomhaven (2017), Oathsworn: Into the Deepwood (2022), Too Many Bones (2017), Nemesis (2018), and Sleeping Gods (2021).

With this wide range on the spectrum from abstract to thematic, it is impossible to divide games into just two categories.

Is there a better way to talk about how a game’s theme and mechanisms are connected?

Shipp’s Layers of Theme

I found Sarah Shipp’s three-layer model of how thematic elements connect to mechanisms to be really interesting! It can give us a way to think about how theme can be connected to mechanisms.

Here’s how it works:

Layer 1: Core Gameplay

Core gameplay is a series of rules and mechanisms that produce an experience even when divorced from theme.

The core gameplay can be extracted from a game, and it still works as a game… even if it might be significantly less fun. The rules, mechanisms, actions, and player decisions could be kept, while all the flavor, art, and lore are stripped away.

Shipp points out that this is particularly easy to identify in cases when you can retheme a game while keeping the core gameplay mechanisms intact. The 20+ reimplementations of Munchkin (Jackson, 2001) are perhaps the best example.

Layer 2: Baked-in Thematic Elements

Baked-in thematic elements are those that cannot be avoided when playing a game.

Shipp gives examples of baked-in elements including illustration, components, icons, graphics, layout, and terminology.

Baked-in elements might not directly impact gameplay, but they also can’t be avoided. The player will always see the art on the board, the shape of the meeples, and the design of a character sheet.

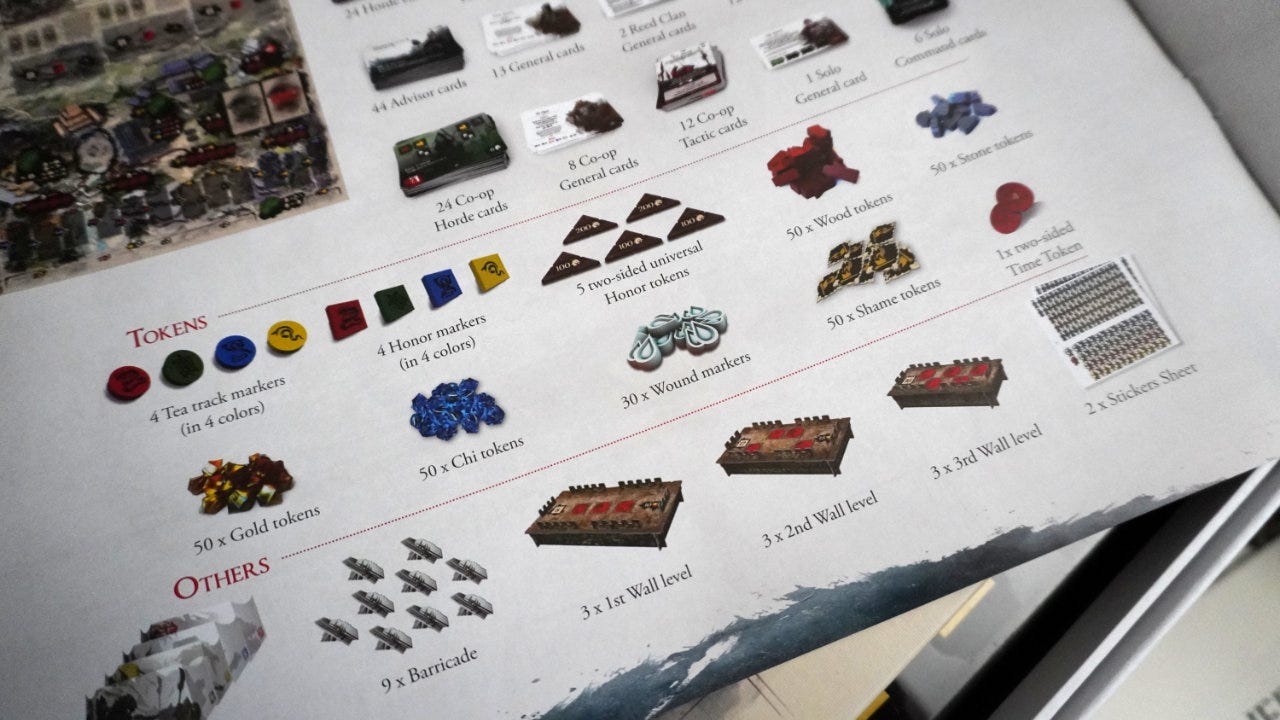

In board games, this often takes the form of miniatures, meeples, and resource tokens. Examples include the style of the metal coins in John Company: Second Edition (Wehrle, 2022) or Architects of the West Kingdom (Macdonald & Phillips, 2018), and the use of miniatures in Cthulhu: Death May Die (Daviau & Lang, 2019).

In TTRPGs, baked-in elements are the ones that the players will see no matter what: character sheet design, player facing dungeon maps, props, and illustrations in the player’s guide.

Layer 3: Opt-in Thematic Elements

Opt-in thematic elements are those that can be ignored during gameplay.

These are the items that designers build into a game, but some players might never see or use. In fact interacting with these elements might actually interrupt the core gameplay.

Long descriptions of game lore, reading narration, and flavor text on cards are all examples of opt-in elements.

Shipp says, “These elements exist for the players who want to engage with them and should enhance the overall experience for those players by working with the other layers and not against them.”

Core gameplay is almost always required to have something called a game. Baked-in elements are necessary to have a theme. Opt-in elements might enhance the thematic design if done well, and will distract from the game if done poorly.

TTRPG System Reference Documents

When thinking about Layer 1: Core Gameplay, TTRPG system reference documents (SRDs) also immediately come to mind!

An SRD is a document that provides the core rules, mechanisms, and guidelines for running a role-playing game system.

It’s usually published by the original game’s designer, with the intent of allowing others to create similar games:

The Carta SRD is inherently themeless, including only rules and mechanisms to design your game. The closest it comes to theme is calling modes “Survival Mode” or “Collect Mode” which, even then, only hint at thematic ties.

The Wretched & Alone SRD includes a section on theme, noting that while most Wretched & Alone games “generally place their protagonists in hopeless and bleak situations where they must do their best to survive or escape,” this doesn’t always need to be the case.

While MÖRK BORG does not have an SRD, the generous third-party license and simple rules have a similar effect.

Could SRDs be made for board games?

Perhaps the closest board games come to this are games that become clearly defined “systems” for other games.

Z-MAN has successfully done this with “Pandemic System” games like Star Wars: The Clone Wars (Ortloff-Tang, 2022) and World of Warcraft: Wrath of the Lich King (Kemppainen, Michlitsch, et al., 2021). Of course, the system is not freely open to use by third-parties, and is not published as an available document.

Applying the layer model to TTRPGs

It’s interesting to think about TTRPGs using Shipp’s three-layer theme model, trying to separate each element into the right layer.

The inclusion of lore:

Dungeon’s & Dragons and other TTRPGs that rely on having stacks of large books seem to go heavy into Layer 3 - Opt-in elements, providing massive amounts of optional lore to read. They usually aren’t necessary and can be skipped, but exist for those who want to read it.

MÖRK BORG and many other OSR TTRPGs focus on Layer 1 - Core Gameplay and Layer 2 - Baked-in elements (e.g. evocative illustrations vs. chapters of lore) to develop a sense of theme.

Optional solo journaling:

I would consider Exclusion Zone Botanist a thematic game. The Layer 1 - Core Gameplay is simple, and the theme is almost entirely Layer 2 - Baked-in elements (e.g. the instructions are blended with the lore). For players who want a more immersive experience, however, the zine edition mentions solo journaling as a Layer 3 - Opt-in option. Players can skip it if they don’t want to interrupt the core gameplay, or add it if they want more theme

Eliminating Layer 3:

Games like MIRU seem to focus almost entirely on Layer 1 and Layer 2, eliminating Layer 3 thematic elements. While I suppose you could skip the tiny introductory paragraph, almost every bit of “lore” in the book is tightly coupled with the core gameplay. It’s not opt-in, and I’d call it more baked-in.

In many ways, Eleventh Beast also has limited Layer 3 opt-in thematic elements. Certainly the inclusion of the Beast Sonnet lyrics is Layer 3, but otherwise everything else is baked-in.

But what about…

As I’ve mentioned before, the (attributed) words of George Box still apply:

"All models are wrong, but some are useful." — George Box

Is Sarah Shipp’s three-layer theme model perfect? Of course not. I’m sure you could identify exceptions and where thematic elements blur the lines between the defined layers.

And yet, much like Bartle’s Taxonomy and the CCI player agency model, the Layers of Theme model gives us a useful way of thinking about games. It gives us a shared vocabulary and framework that can be used to describe how thematic elements interact with the mechanisms of the game.

It also can aid in game design, as Shipp notes (p. 12):

Understanding how theme is expressed in the different layers of a game’s design can help you identify where your theme may be weak or underdeveloped. You may discover that you skip to layer 3, opt-in elements, in your design and would benefit from spending more time focusing on the thematic expression of core gameplay.

I’m looking forward to finishing Thematic Integration in Board Game Design, and exploring how the lessons apply not only to board games but also to TTRPGs.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Thematic design is important: Rules and mechanisms tell us how to play a game, but the theme tells us “why” we play the game. The theme is inextricably tied to player promises, the ability to teach the game, and crafting a specific player experience.

Shipp’s Layers of Theme is a useful model: The simplicity of the three-layer theme model makes it easy to use and useful when engaging in game analysis or design. It’s a fun exercise to take a game you know and try identify the layer for each element.

Layer 3 elements can interrupt core gameplay: It’s an interesting observation that skippable elements (i.e. opt-in) almost always interrupt the gameplay. Players will either skip the element or potentially be frustrated by it. When is the last time you read all the flavor text on game cards? And yet Layer 3 can also be a powerful thematic tool.

What do you think? Is the Layers of Theme model useful for game analysis and design? Does it apply equally to board games and TTRPGs?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Lone Adventurer did a playthrough of Eleventh Beast by Exeunt Press! You can watch Part 1 and Part 2 on Youtube. Hit that like button and subscribe. 😉

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

That's a great article. I really value minimal, tight, and thematic design in games that I read, play, or design, and those usually have minimal Layer 3 - opt-in thematic elements. I'd rather have that type of theme come from play, not before play.

Interesting analysis. For RPGs there's the additional consideration of how much of each layer is presented to the GM vs. to the regular player.

Players are often getting layer 3 thematic material *via the GM*, but that could be something from a rulebook or created by the GM themselves. Some players may not look at the book at all, and get almost everything (beyond their character sheet) via the GM. There's an implied design question there about how we (as designers) construct the role of the GM as a component of the mechinary of delivering theme.