Open information vs. hidden hands in The Tea Dragon Society Card Game

Exploring how small changes to the usual deck-building game conventions make The Tea Dragon Society Card Game a bit more accessible (and cozy) to a wider range of players

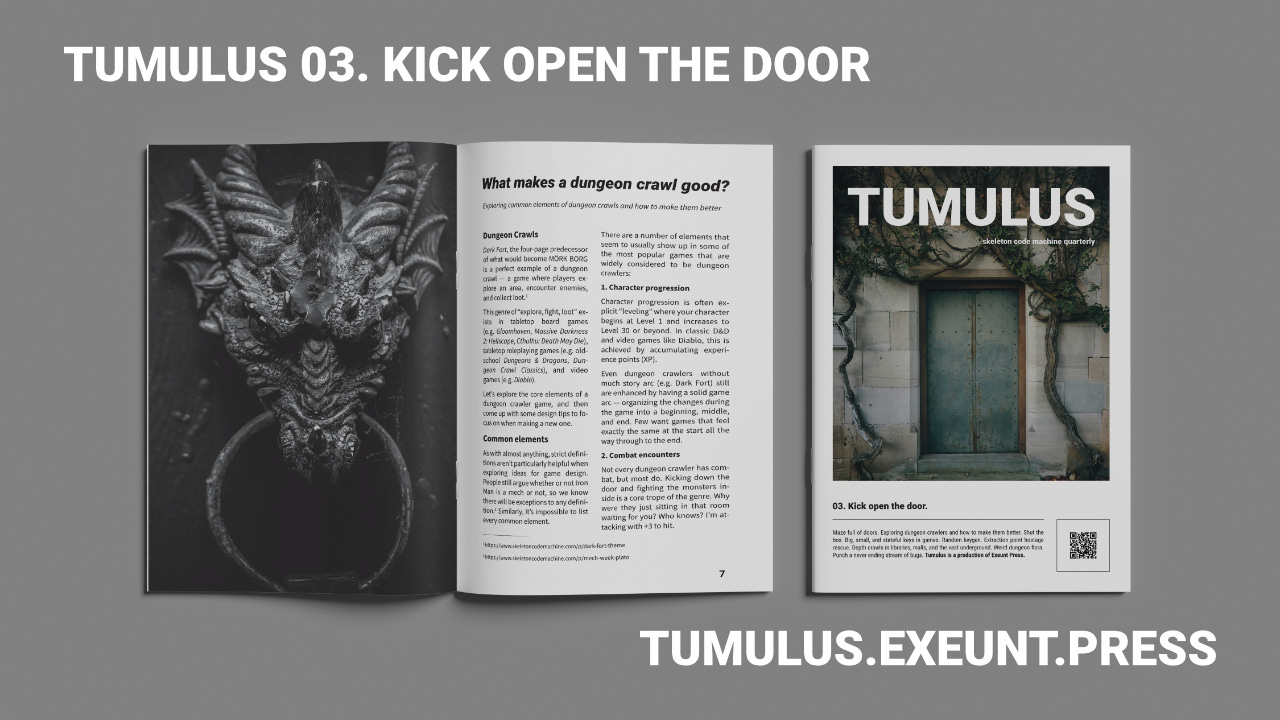

Last week saw the launch of the latest issue of Tumulus with many subscribers probably receiving their copies this week. The theme for this issue is “Kick open the door.” — the anticipation and excitement of kicking open doors, opening chests, and other moments of explosive revelation. It includes original articles by Jesse Ross (Trophy, Girl Underground) and Hinokodo (MIRU, Pondus).

In addition, how Gladiator (Greenwood & Matheny, 1979) uses mechanisms to support the theme of combat and a fickle crowd in the arenas of ancient Rome.

This week we are looking at how The Tea Dragon Society Card Game modifies the deck-building genre to make it a bit more accessible for kids and new players.

The Tea Dragon Society Card Game

Based on The Tea Dragon Society graphic novel series by K. O’Neill, the The Tea Dragon Society Card Game (Ellis & Tinsley, 2018) has players taking care of adorable dragons:

Discover the ancient art form of Tea Dragon caretaking within this enchanting world of friendship and fantasy. Create a bond between yourself and your Tea Dragon that grows as you progress through the seasons, creating memories to share forever.

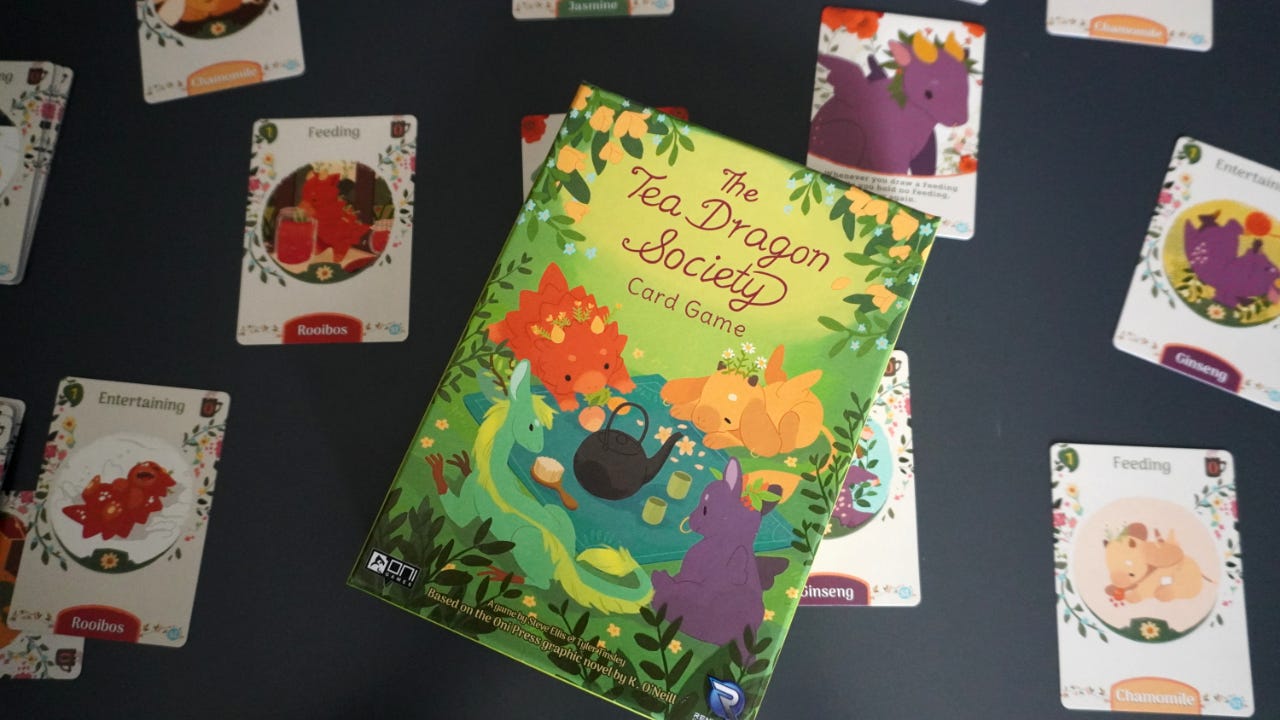

Over four seasons, each player will play cards such as Entertaining, Sleeping, and Grooming to collect better cards representing iron teapots, musical instruments, brushes, treats, and wind chimes.1

At the end of winter, the game ends.

Simple deck-building to score VP

Mechanically, The Tea Dragon Society Card Game is a deck-building game.2 That is, players begin the game with simple starting decks of cards and use those to purchase more powerful cards into their deck. The new cards have higher values that allow even more cards to be purchased.

Specifically, each player begins with a deck representing their tea dragon — each with slightly different starting cards. Most have a 1 or 2 Growth value (i.e. the currency of the game) on them, along with a couple Mischief cards (e.g. picky, bite, or grumpy).

Players take turns either drawing a face-down card from the deck or purchasing a card from the static markets.3

One market has standard cards that are similar to the ones in the starting decks, but with higher currency values or a minor ability. The other market has memory cards that are worth the most victory points (VP).

The game is triggered when there is only one winter memory card left on the table. Most VP wins.

Open information holds vs. closed hands

One interesting twist in The Tea Dragon Society Card Game is that players never take cards into a hand. This is in opposition to most competitive deck-builders such as Dominion, Undaunted: Normandy, and Shards of Infinity.

Instead, cards are placed into a “hold” on the table. All the cards in the hold are face-up and open information for all to see. When a player wants to purchase a card from the market, they take the necessary cards from their hold and place them in their discard pile. The newly purchased card goes directly into their hold.4

The open holds instead of hands helps young players and changes the game in a few notable ways:

Holding cards can be hard sometimes. Sure, it’s easy with some practice, but removing it means one less thing to worry about.

With effectively open hands, it’s easier to help young players with the game without being overly intrusive. You don’t need to stop the game or ask, “Can I see your cards?” Instead, it’s easy to glance over and see if they are struggling.

It reduces the “head to head” competitiveness of the game and, while it is far from a co-op game, makes it feel more relaxed and cozy — perfectly on theme.

Trying to implement open information hands in most competitive deck-builders would break the game. I’m not suggesting this is a best practice for all deck-builder design. This wouldn’t work in a game with more take that or kill steal mechanisms.

It is, however, a perfect example of modifying the standard mechanisms of a genre to better fit the theme of the game — friendly tea parties.

The game says ages 10+ but with open information cards, I have no doubt younger children could easily play.

Illustrated rules introduction

One side note that I have to mention is the inclusion of an illustrated “learn to play” booklet. Written and designed like the graphic novel, it uses three characters from the books and panels to walk through an example session. It’s cute and I found it to be quite helpful! The game includes a regular rulebook as well, but it was a nice surprise to see the learn to play.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

There’s room for innovation in deck-builders: Ever since Dominion, there have been countless deck-building games published. Some are, admittedly, rather derivative clones of Dominion. Others have taken the genre in completely new directions. Even old genres can be modified and adapted to fit a new theme or kind of fun.

Competitive doesn’t need to be mean: I love competitive games, including some particularly mean games like John Company: Second Edition and Root. I don’t even mind king making. That said, it’s also nice to have some lightly competitive games available that can be played with a wider range of players.

Think about the target players: This year I’ve really been thinking about how important the question “Who is this game for?” is when designing a game. I made a point of covering it in my most recent public library game design class. Some of the design choices in The Tea Dragon Society Card Game wouldn’t work in other games and for other types of players.

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Support Skeleton Code Machine with a purchase at the Exeunt Press Shop!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

It is the position of Skeleton Code Machine that wind chimes are rarely, if ever, allowable.

For a look at how deck-building can be used in a wargame, check out the negative optimization article on Undaunted 2200: Callisto — a game I’d like to get to the table more often than I do. I personally prefer it over the WW2 themed original.

While the market is refreshed at the end of each of the four seasons, I’d still consider it to be a static market vs. a dynamic market. There is no built-in mechanism to continually remove cards and add new ones, nor is there a way to make stale cards more desirable.

Memory cards are an exception to this and go into the discard pile. This article is not a full rules explanation.

I have read the comic, and it really is lovely – had no idea there was a game, so thank you for introducing it to me :) seems like a really perfect adaptation ^^

I can confirm on this games accessibleness . I bought this game for my family to play.. then 10 and 13 year old kids. They loved it and I immediately bought the stand-alone expansion, which improves on the base rules a bit, and can be combined into a single larger game accommodating more players. I highly recommend this one.