The moment of truth approaches!

Exploring how Gladiator (1981) uses mechanisms to support the theme of combat and a fickle crowd in the arenas of ancient Rome.

Last week I published an updated list of the best articles you may have missed at Skeleton Code Machine. It’s been a year since I’ve done that and we’ve picked up 2,000+ new subscribers since then!

Also, Tumulus Issue 3 is shipping now and includes contributions from Jesse Ross (Trophy, Girl Underground) and Hinokodo (MIRU, Pondus). Subscribe to get this issue as the first of your four quarterly issues packed with creative inspiration.

And now we enter the arena…

Gladiator

Originally part of Circus Maximus (Greenwood & Matheny, 1979), Gladiator (Matheny, 1981) was split off into a separate game for publication:

GLADIATOR is a simulation in a game format of man-to-man combat in the arenas of ancient Rome. The game is played by two or more players, each controlling one gladiator, thus providing the opportunity for individual matched pairs as well as team combat depending on the number of players present. The games provides all information necessary to recreate this ‘sport’ of the ancient world accurately with all of its vicarious thrills.

For an Avalon Hill game from the 1980s, while the rules are still written in the style of the time, they are surprisingly understandable compared to most.1 The main mechanisms are rolling dice and looking up the results on a combat results table (CRT) — the anvil of probability!

I won’t cover all the rules, but instead want to focus on (1) combat and (2) appealing to the crowd.

Combat in the colosseum

In Gladiator, combat is conducted on a hex map with cardboard standees. This means that each gladiator has a position and a facing relative to each other. Facing your opponent allows for an attack to be made, possibly with a bonus for catching them facing the wrong way.

Each player calculates how many Combat Factors (CF) they have and then spends them for attack and defense on their sheet.2 CF spent on attacks are allocated to five body areas (head, chest, upper torso, lower torso, legs) as shown on a diagram. The same is done with CF spent on defense. These are secretly recorded by each player on their player sheet.

The players then simultaneously reveal their attacks. Each body part is a separate attack and multiple attacks get put into a sub-phase sequence.3

The attacker says how many CF they allocated to the attack (“2 CF attacking arms”) and the defender says how many CF they allocated to defending that body part. The values are subtracted and three dice (3d6) are rolled to resolve the attack using a combat results table.

Possible results include missing, no effect, shield hit, shield edge hit, parried with weapon, parried with weapon and shield, body hit, and severe body it. From those rather detailed results, wounds are determined. There are additional rules for shield damage, dropping weapons, kneeling, and more.

The moment of truth

The part that caught my eye in Gladiator is a small section of the optional advanced rules called The Moment of Truth:

19.1 Any time a gladiator starts a phase by being prone [in front of] an adjacent armed opponent and is helpless by virtue of being ensnared in a net, or unable to move during that phase, or unconscious, the Moment of Truth arrives… In the Moment of Truth the crowd must decide the fate of the unlucky gladiator. Since the crowd prefers a lengthy, aggressive match, the following system is used to determine the popular response.

The way the Moment of Truth is determined is really interesting:

The downed gladiator counts up all CF used for attacks during the game and all CF used for defending during the game.

The number of defense CF is subtracted from the number of attack CF.

The resulting value is used with a die roll (1d6) on a Missus Chart to determine the reaction of the crowd.

A die roll of 1 is always a thumbs down from the crown, resulting in death.4 Your chances increase with a higher Net CF (i.e. attack CF - defense CF). At a Net CF of 15 or less, you have a 1 in 6 chance (~17%) of being spared. Even 50% chance at 31-45 Net CF and 83% chance at 61+ Net CF.

Spending more time attacking in the game increases your chances.

Fortune favors the bold

This is an exceptionally thematic way to simulate asking the crowd to be spared!

The Roman crowds love a good fight, so the more fighting you did (i.e. allocating CF to attacks) will sway their opinion. Less fighting (i.e. allocating more CF to defense) will not win over the crowd. In fact, Rule 19.21 says that if the net CF is zero or less, the result will always be thumbs down regardless of the die roll.

While I’m sure many (most?) fights will result in the death of one of the gladiators, I love this addition to the advanced rules. I can only imagine the tension of that final die roll to see what the fickle crowd will say!

A side note about fighting beasts

I just couldn’t resist including this, so please bear with me. Pun intended.

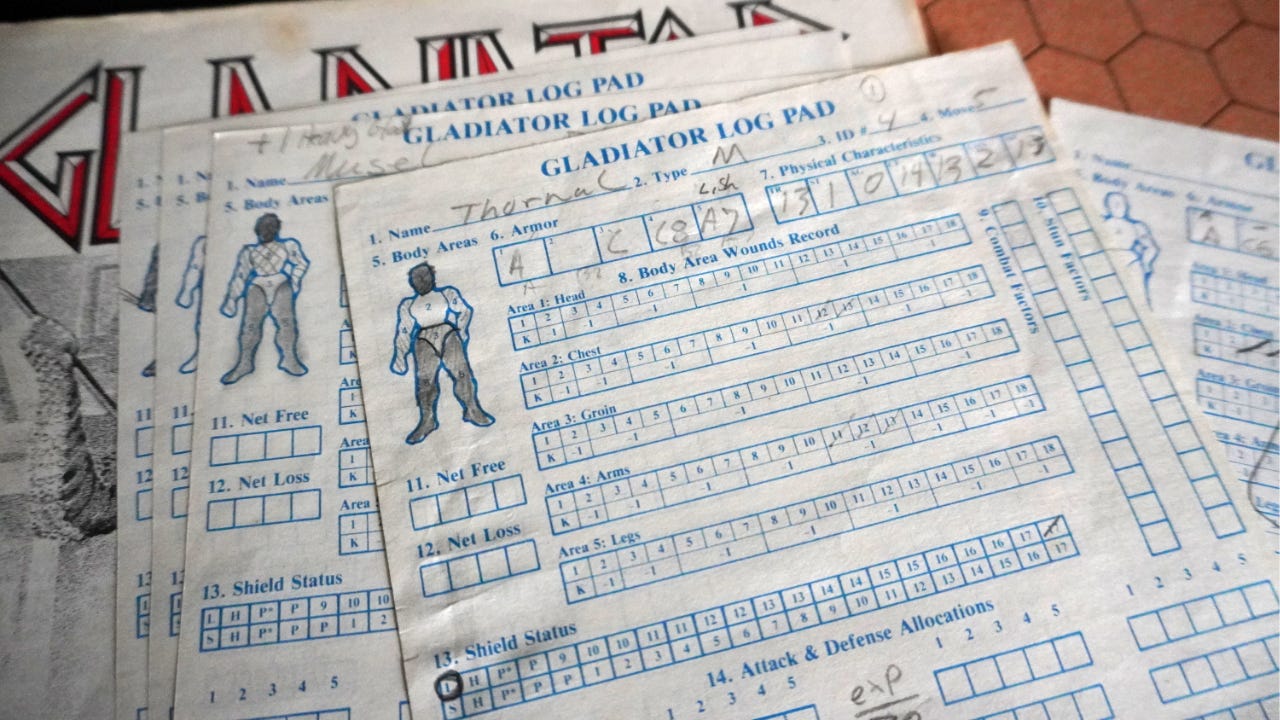

The copy of Gladiator that I have came from a charity auction at the Save Against Fear tabletop game convention. I don’t know who the previous owner was, and the game isn’t in great condition. Many of the play sheets are used, there is significant discoloration, and the pieces are a little rough.

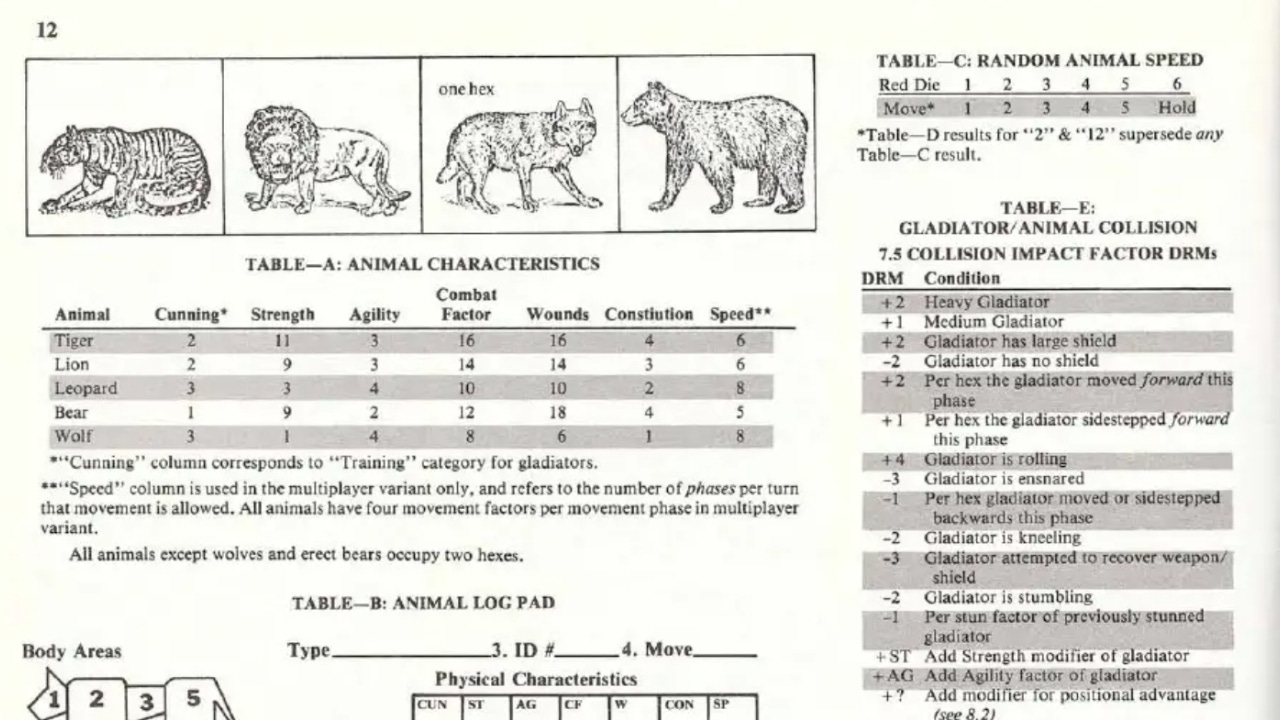

But included in the box were some clearly handmade pieces in the game — specifically a tiger, lion, wolf (one hex), and bear. Animal combat is not mentioned in the rules. Perhaps the owner made their own rules and scenarios?

While doing research for this article, I came across Avalon Hill’s magazine The General Volume 18, Number 4 from 1981. Gladiator is featured on the cover and inside there’s an article by Thomas C. Springsteen which begins with high praise for the game:

GLADIATOR, one of Avalon Hill’s most recent game releases, can only be described as a gaming phenomenon. I have never known a game to attract such quantities of players from so many other varied subject, scale and period interests.

And then I saw the article had rules for solo and multiplayer combat versus beasts!

There were the four animals: tiger, lion, wolf (one hex), and bear in their original art! The custom pieces in the board matched the originals, clearly made with care.

I really loved finding the inspiration for the drawings and the artifacts of someone’s love for the game from over 40 years ago!5

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Arena combat seems evergreen: I’m not sure 1v1 tactical combat games that pit opponents against each other in a skirmish or arena will ever go out of style. They seem to be continually popular. Probably not a bad place to start if you want to try you hand at making games.

Use mechanisms that support the theme: I’ve written about the connection between theme and mechanisms and how mechanisms should support the theme many times before. Appealing to the crowd for a vote is another perfect example.

Don’t worry about dings and dents: The copy of Gladiator I acquired is in rough condition. It’s stained, ear marked, bent, and includes custom pieces cut from scraps of cardboard and drawn with a blue pen. And I can’t imagine how much fun the previous owner had playing this game! The completed play sheets with names Ardbor, Thornal, Mangladen, Musel, Mand, Arthur, and Tory are wonderful artifacts of play.

What do you think? Have you played similar arena combat skirmish games?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

BGG weight for Gladiator is 2.86/5 which is maybe accurate, but only if you are very familiar with wargames and their common mechanisms.

I’m not sure why the word “factor” was so popular in 1980s wargames. In a modern game we’d just call these action points or perhaps combat points.

Even though the attacks are thematically happening at the same time, mechanically they are resolved one at a time. The order matters considerably as each attack could end the game. The exact order they are resolved depends on how many CF are allocated to that attack.

Was a thumbs up or thumbs down good? There’s much debate and a few urban legends regarding this. I’d recommend starting with some reading about the pollice verso.

Yes, 1981 was 44 years ago.

Titan is another Avalon Hill game that includes arena combat. It has gone through multiple editions , including one recently from Valley Games. The people at my game club played it obsessively for years, so there must be something to it. And it also has at least one cover of The General devoted to it.

Thanks for all your insights into game design, by the way!

I remember this game, and still have my copy that I got used in the 1990s. Much fun was had fighting battles against my younger brother's gladiators. We found the system a bit clunky, but overall the game is fun. As a teenager I tried coming up with variant rules for different fantasy races (elves, dwarves, trolls, etc.) but I don't remember coming up with anything I found satisfactory.