Dynamic markets and Dutch auctions

Mechanisms designed to keep card markets moving

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Last week we looked at dice management and strong actions using Troyes as the example. As a side note, while taking photos for the article, I discovered there is a solo mode in the box! Looking forward to giving that a try.

This week we are exploring a very specific tabletop game mechanism that I’ve seen in quite a few games, but wasn’t exactly sure what to call it. It’s one of my favorite mechanisms and elegantly solves some problems that routinely show up in games with markets.

The 2024 One-Page RPG Jam is over, but you can still make games. The Make Your Own One-Page Roleplaying Game guide from Skeleton Code Machine will help you get started!

Open drafting and card markets

It’s important to define some terms up front when discussing drafting and markets. The terms open drafting and market are sometimes used interchangeably, but there is a distinct difference:

Open Drafting: Mechanism where resources or components are in a common pool (or pools) and visible to all. Players then take turns selecting items from the common pool to build their own private collection. This is commonly done with cards, where each player selects one of the cards from the common pool and adds it to their hand. Examples include Saint Petersburg (Brunnhofer, 2004), Azul (Kiesling, 2017), and Dominion (Vaccarino, 2008).

Market: A true market mechanism is one where players are buying and selling resources. Sometimes this is used as an economic simulation where buying increases prices and selling decreases prices. Examples include Power Grid (Friese, 2004) and Clans of Caledonia (Al-JourJou, 2017).

At some point the idea of open drafting from a display of face up cards became known as a market. I assumed this was from Dominion, but the rulebook just calls the cards Kingdom Cards and refers to the collection as the Supply. Similarly, Ascension: Deckbuilding Game (Gary, Fiorillo, et al., 2010) just call it the Center Row and never calls it a market. Pax Renaissance: 2nd Edition (Eklund & Eklund, 2021) does, however, explicitly calls the cards a market.

Regardless, I will use the terms interchangeably: A card market is where there are multiple, faceup, cards displayed on the table and players are choosing from them.

Static vs. dynamic card markets

There are two major types of card markets that are defined by how cards are cycled through them:

Static: The cards do not frequently change during the game and/or they only are refreshed when a player takes a card. All cards that will be available during the game are available right from the start. Dominion (base game) is an example of this where the Kingdom Card piles are selected at setup and do not change.

Dynamic: There are mechanisms built into the game to ensure that the market is always changing and refreshed. There can be a large variety of cards in the game and only a subset of the total cards are available during play. Ascension, Shards of Infinity, Pax Renaissance, and Pax Pamir are all examples of games with dynamic card markets.

The Quest for El Dorado (Knizia, 2017) has an interesting mix of static and dynamic card markets. There are two rows of piles of cards. The top row is only “unlocked” and made available when the matching bottom row pile has been exhausted.

Other games also mix static and dynamic markets simply by having two markets: one is dynamic and cards are revealed during the game, and the other market is static and always available. Ascension does this with the static Mystic, Heavy Infantry, and Cultist cards that are always available.

Clogged up dynamic markets

One problem that can arise when a game has a dynamic market is that it can get “clogged” with unwanted cards.

This can occasionally happen in Ascension: Deckbuilding Game if neither player wants to purchase or defeat certain cards in the market. The unwanted cards will take up some of the six available spots in the market, slowing down the introduction of new cards. As a dynamic card market, this means players will see less variety of cards over the course of the game.

Ascension is a well-designed game and eventually forces players to buy cards from the dynamic market if they want a chance of winning. So the issue is not a game-breaking one.

It is, however, an issue worth thinking about…

Keeping dynamic markets moving

I’ve seen two methods to keep dynamic markets cycling and dynamic that are really interesting:

Discard: This one is simple: discard a card from the market each round. It works best when cards are arranged in a single row or line. Usually the leftmost card is discarded, all other cards slide to the left to fill the spot, and a new card takes the empty rightmost spot.

Incentives: Coins or resources are placed on cards. When a player takes that card, they also gain the resources (e.g. coins) that were on it. This provides an additional incentive to choose a suboptimal card just to get the resources.

I have three examples where I think these methods are very effective:

1. Pax Renaissance

In Pax Renaissance: Second Edition there are two dynamic card markets: East and West. Each has its own draw pile, seeded with comets. Each market is arranged in a single row, similar to the Center Row in Ascension or Shards of Infinity.

Instead of paying Florins (i.e. the coins in the game) directly to the bank, players place the coins on the cards ahead of the one they want to purchase:

The purchase price of a card depends on its current column in the Market. The first faceup Market card costs 1 Florin, the next 2 Florins, then 3 Florins, etc. Pay this cost by placing 1 Florin on each card in the same row to the left of the card you are purchasing.

This means that less desirable cards will gradually get more Florins stacked on them, making them increasingly attractive. There might be so many coins on a given card that a player will take it just to get the coins.

This incentive system is combined with a fairly standard dynamic market refresh system where cards slide to the left. After each player finishes their actions, they refresh the market:

If there are gaps in the Market after you perform your actions, starting with the leftmost card, move each card in the Market (along with any Florins on it) to the leftmost empty position in its market row. Then draw new cards to fill any remaining empty market positions so there are again 6 cards in each row. To do this, draw cards from the respective East or West draw deck and fill the rows from the leftmost empty slot. If either of the cards in the leftmost column are faceup, flip them to their facedown (trade fair) side.

In addition, Trade Fairs in the game cause the leftmost (face down) card to be discarded. This allows cards to be purged out of each market and ensures that it will never be clogged up.

Pax Renaissance uses discarding, incentives, and market refreshes to ensure the market never clogs up and is highly dynamic.

2. Pax Pamir

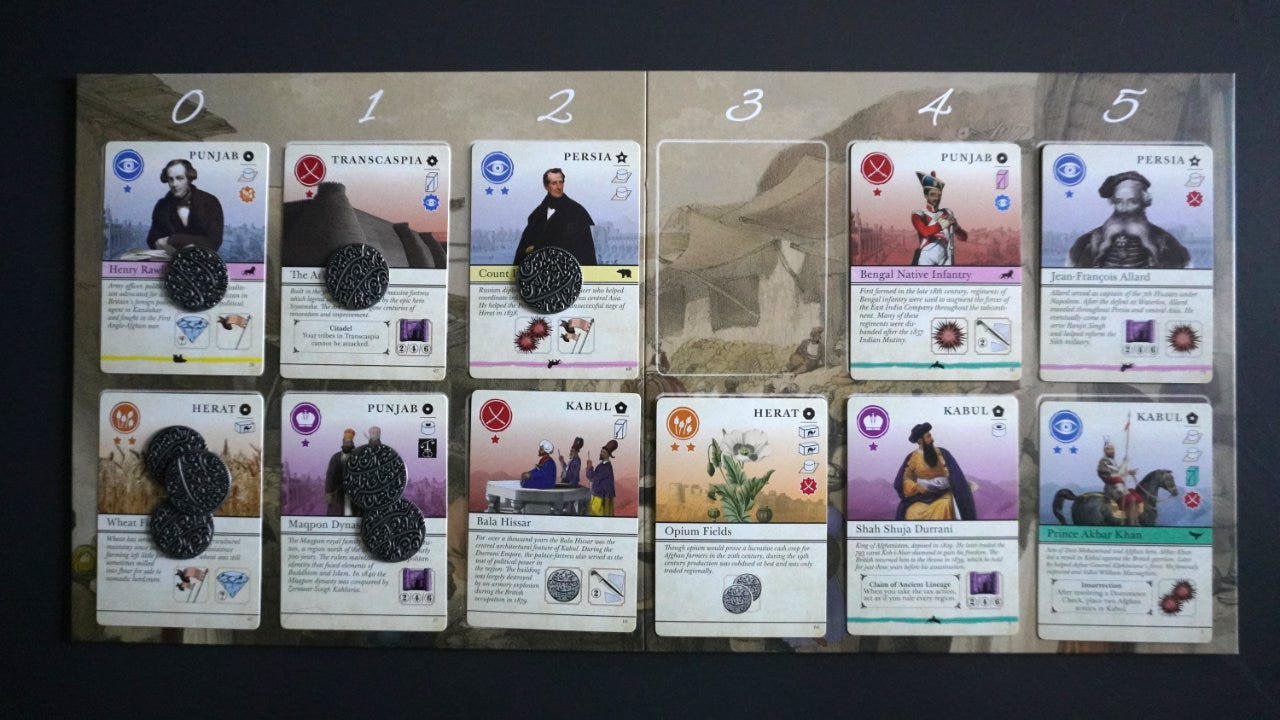

It’s easy to see the “Pax” roots in Pax Pamir: Second Edition (Wehrle, 2019). Just like Pax Renaissance, it has a two row market each with its own draw pile. Each row has six cards just like the East and West markets in Pax Renaissance, but all cards are face up rather than the leftmost being face down.

Purchasing cards works in a similar way. To purchase a card and add it to your hand, you pay the cost of the card to the market (not the bank or supply). The cost of the card depends on its position in the market, with the leftmost card being free. Subsequent cards moving to the right are one, two, three rupees (i.e. coins) and so on.

You pay the coins by placing one coin on each card ahead of the one that you want to take. Because the card refresh happens once per round vs. once per turn, any gaps in the market mean the coin goes to the other row.

This timing on market refreshes is different than the one in Pax Renaissance. It happens once per round during Cleanup. It also forces the leftmost card to be discarded every time, as opposed to only during Trade Fair actions in Pax Renaissance.

The market is kept dynamic by frequent discarding and the coin incentives, even though the market refreshes are less often.

3. Canvas

The last example is Canvas (Chin & Nerger, 2021), a beautiful and lightweight game about creating paintings in an art competition. I played it for the first time this week, and was pleasantly surprised to see how art cards are drafted!

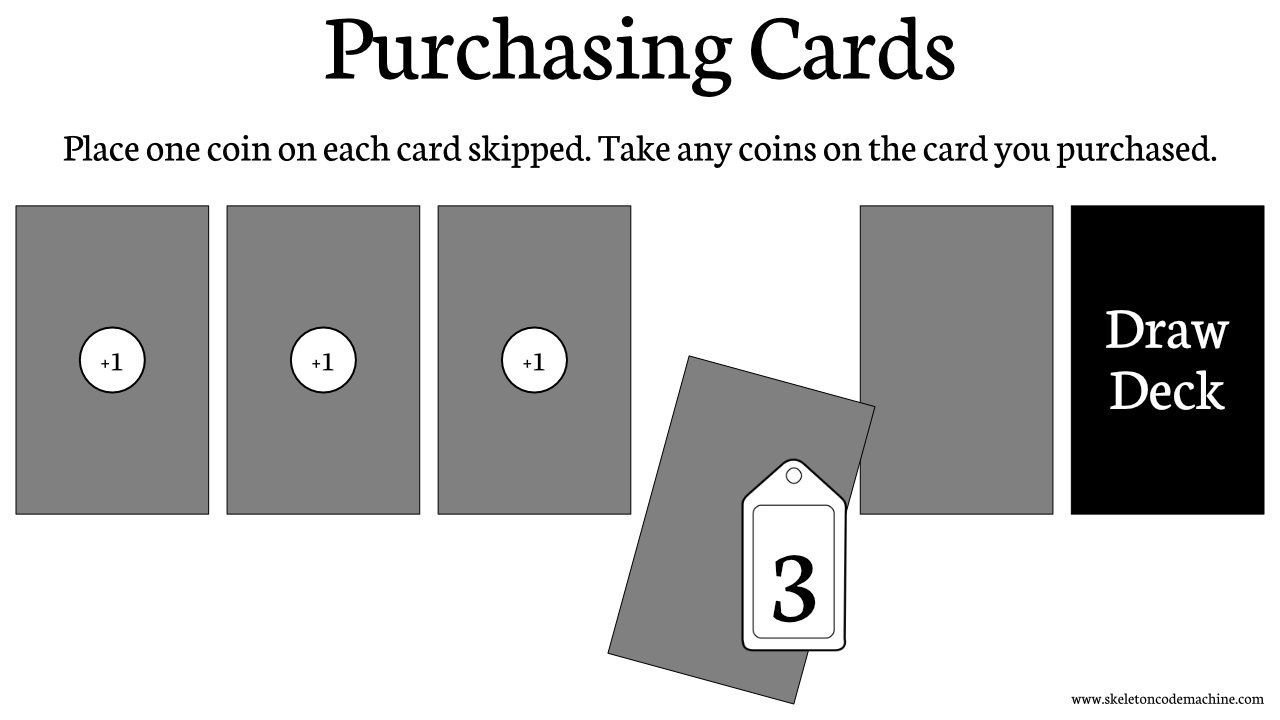

Art cards are arranged in a single row of five cards. On your turn you must either take an art card from the market, or complete a painting using the cards in your hand.

To take a card you can either grab the leftmost one (i.e. farthest from the deck) for free, or you can skip across cards to take a different one. You place one Inspiration Token (i.e. the equivalent of a coin) on each card that you skip over, just like Pax Renaissance and Pax Pamir. If the card you take has Inspiration Tokens on it, you get the tokens as well.

The market is refreshed with a new card from the deck each time a player takes a card, and they all shift to the left.

It’s notable that there is no discard mechanism in Canvas. If a card is unwanted, it will just continue to accumulate Inspiration Tokens. In practice, someone will eventually grab that card because it has a pile of tokens and the market will continue to be dynamic.

Canvas keeps the market dynamic using incentives and refreshes only, and does not use a discard mechanism.

Does this mechanism have a name?

What do you call this mechanisms where players place coins/resources on skipped cards, and take any coins/resource on the card they take?

Once again, Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design by Geoff Engelstein has a possible answer. Pax Pamir: Second Edition is given as an example of a Dutch Auction, but one that is spread out over multiple turns! That’s it!

A Dutch Auction works like this:

A simultaneous single-bid system in which the lot starts at a very high price, and then is gradually decreased by the auctioneer or other controlling mechanism, until someone agrees to claim the item at its current price, ending the auction. The first bidder to accept the current price is the winner, such that there are no ties. A Dutch Auction is sometimes also called a one-bid auction because of this feature that the first bid made is also the only bid in the auction.

While not exactly a Dutch auction, the similarities are striking. The important twist seems to be that players are the ones adding coins to the cards, thereby lowering the effective price of each card. The “price” of a card can go negative, meaning that when the player takes the coins they actually made money on the purchase!

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Keeping markets dynamic: Dynamic markets are fun and allow for a wide variety of cards to be used vs. static markets. Care must be taken, however, to ensure that the market stays dynamic and the cards keep moving. Incentives, market refresh timing, and discard mechanisms are a few ways to solve this design problem.

Mixing static and dynamic: Many games mix types of markets to make a system that feels dynamic, but still has the benefits of a static card market. You don’t need to choose just one type of market.

Many types of auctions: There are so many types of auctions that can be modified and adapted for use in tabletop games. Some auctions can be modified so much that it’s not obvious they are auctions! That’s certainly the case in the examples given above.

What do you think? Do you prefer static markets or dynamic markets in games that use cards?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “I also love the idea of a demon being on a PIP. Excellent work!” Try Caveat Emptor for free, or get the 36-page Expanded Edition for just $5. 😈

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

I wish this article had come out a couple of weeks back while I was working on the Market Mechanic for my one page game! Really good round up of various market mechanics, I'll need to dive in for a bit more research!

This shows up in Garphill Games' Architects of the West Kingdom too, though with a bit of a twist. The number of workers you place on the marketplace space notates your level of access to the card row, but you can always pay to jump farther down the line. Does it show up in Scholars of the South Tigris too? I seem to recall there were mechanisms for moving about in the card row.