What is a probabilistically equivalent mechanism?

Exploring how the choice of cards, dice, tokens, coins and how the player physically interacts with can support (or break) the theme of a tabletop game. There's more to it than equivalent probability.

Last week we looked at when randomness is OK in games, specifically about how random events in highly thematic games can create lasting memories.

This week we are exploring the thematic integration of mechanisms in tabletop games. It’s a topic we’ve looked at before in the thematic design of Dark Fort and the components of Inhuman Conditions.1

But what if the mechanisms can be swapped with simpler ones? What if the change is mechanically equivalent and doesn’t impact the overall game?

Well, it might matter more than you think…

Rolling dice and flipping coins

Imagine a game mechanism where the player takes an action and they need to see if it is successful or not — attacking a skeleton, jumping across a chasm, whatever.

Here are four different ways we could do that:

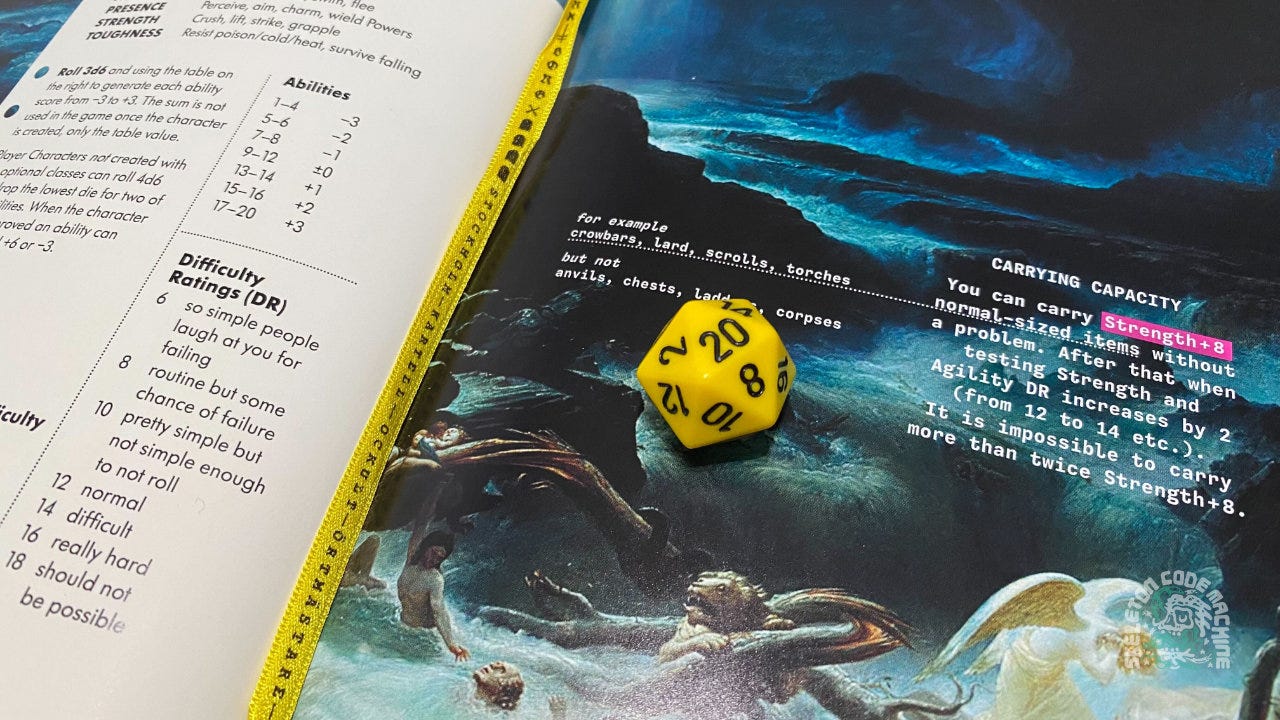

Roll dice (d6): The player rolls 1d6. They are successful on a roll of 1-3 and fail on a roll of 4-6.

Roll dice (d20): The player rolls 1d20 vs. a target of 10. On a roll of 11-20 they succeed fail on a roll of 1-10.

Coin flip: The player flips a coin or token. Heads they succeed. Tails they fail.

Card draw: The player draws a card and compares vs. a target number of 8. Jokers and aces are removed. Face cards are counted as J=11, Q=12, K=13. If the rank is 2 - 7, they fail. If it is 8-13, they succeed.

Bag draw: There are 20 glass tokens in a bag; 10 red and 10 black. The player blindly draws a token. Red is success and black is failure.

These five methods use different components, have different rules, and require different amounts of dexterity.2 We’d easily and correctly identify them as different mechanisms. They’d also be, however, examples of probabilistic equivalence — their underlying probability distributions are the same.3

All five of them have a 50% (1:2) chance of success. Whether it’s rolling dice, flipping a coin, or drawing cards… it’s always a 50/50 chance.

So the question is, why would you use one vs. the other?

Does it matter?

The face down artifact card

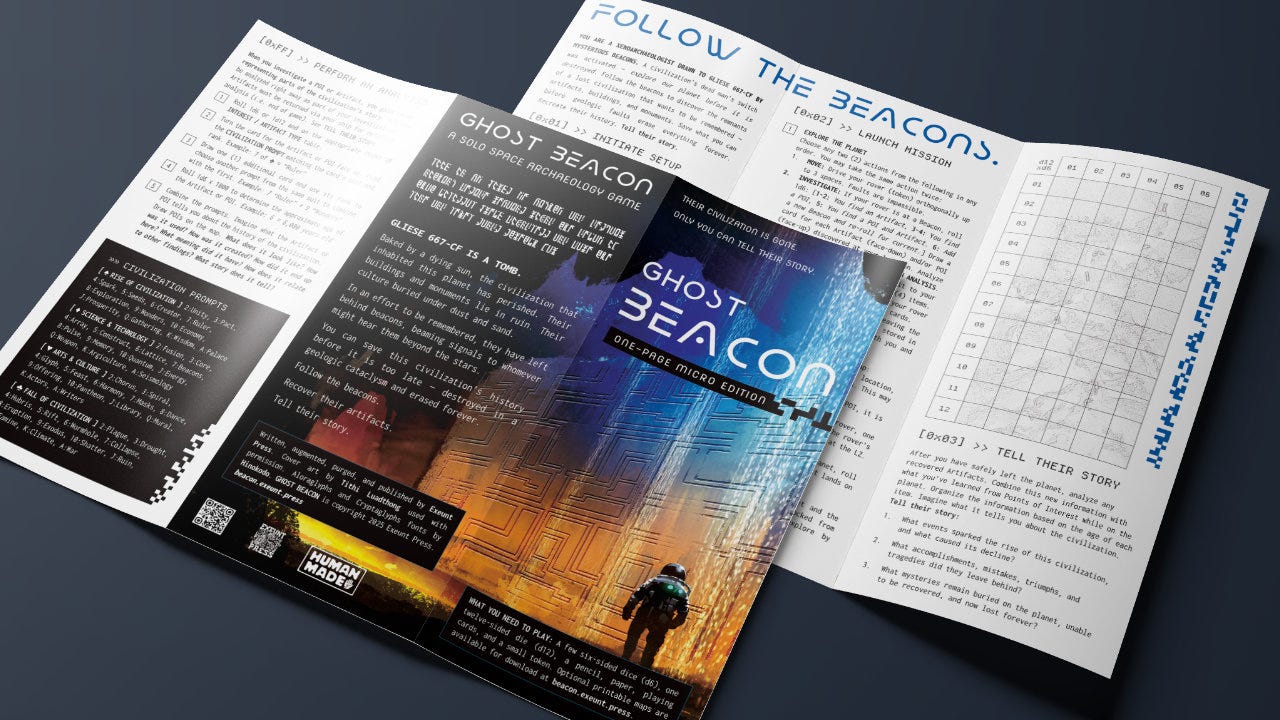

As I continue to work on the full version of Ghost Beacon, I’ve been revisiting some of the core ideas.4 For example, it uses both dice and a standard deck of playing cards. Is the deck of cards truly necessary? Is there some way to remove that requirement and simply use dice instead?

As a quick overview of the game:

You are a space archaeologist driving around an alien planet that’s about to be torn apart by earthquakes.

Your goal is to study points of interest (POI) and recover artifacts of a lost civilization before they are all destroyed — gone forever.

The civilization’s story contained in each POI or artifact is represented by playing cards drawn from a deck.

You can analyze POI right away, drawing a card and looking at it. Artifacts are, however, more complicated. They can only be collected and analyzed after you’ve left the planet. Artifact cards are drawn when the item is discovered but then kept face down until the end of the game.

The game therefore has two distinct halves as a player recently noted:

“I like the balance of the game, where the first half has you racing around collecting items before your retreat is blocked, and the second part (assuming you make it) is a bit of a puzzle where you are asked to fit together everything you've found into a story. Both parts are fun for different reasons.”

While discussing this with another designer I know and trust, we had the following exchange about switching from cards to dice:

EP: I think I have to keep the cards in the game. It's the only way to have hidden information (un-analyzed artifacts) until the end of the game.

M: What’s the difference between a card you haven’t flipped and a tick in a checkbox that makes you roll dice later?

This is a fascinating question! And it really made me thing about why I felt the need to keep cards vs. just using dice. What is the difference?

To me, this is why it matters:

Collecting: Cards support the thematic sense of “collecting” things while playing. By drawing cards from a pile and placing them in front of you, you physically collect objects.

Storing: Thematically, a limited number of cards may be stored in your rover. The cards drawn show this even at a glance. You can feel the storage filling up without managing a number, die, or other tracker to know when the storage is full.

Analyzing: The information is fixed but hidden until the end of the game. This feels completely different from (a) drawing the cards at the end, or (b) rolling dice to generate artifacts at the end. You know the information is there — you just can’t access it yet. It remains hidden until you end your time on the planet.

I’m sure there is a technical term for this — ludonarrative dissonance perhaps? Or it could be as simple as calling it thematic integration. Either way, it can be incredibly important when crafting a specific player experience.

The stacking block tower salvage ship

The Wretched by Chris Bissette was an important game in my introduction to solo TTRPGs.5 It’s a tense game with an Alien-esque space horror theme:

You are the last surviving crew member of the intergalactic salvage ship The Wretched. Adrift between stars after an engine failure, your ship was attacked by a hostile alien lifeform. The crew are dead. You thought you had won. You launched the creature out of an airlock, and that should have meant safety.

Along with journaling prompts, The Wretched uses a stacking block tower (e.g. Jenga) as a core mechanism. As part of the core game loop you draw playing cards from a deck. Some of the cards instruct you to pull from the tower — removing a block from the bottom and placing it on the top. This represents the state of your ship becoming ever more precarious. Each pull edging you closer to disaster.

It’s a beautiful, thematic mechanism that converts the narrative tension of the game into something you can see, feel, and touch. I quite literally held my breath as I placed pieces, hoping I could survive another pull.

Would a different, probabilistically equivalent mechanism have been the same? Hardly.

Chris commented on this recently (thread):

“…but this is something I thought about a lot when I released The Wretched. People immediately wanted to find ways to play it without a Jenga tower, and while I respect that, in a lot of ways the Jenga tower *is* the game.”

“I spent a lot of time - five years, in fact - coming up with a mechanism I liked as much as Jenga for creating rising tension and I eventually put that into Blood In The Margins. I'm very happy with how that works, but it's definitely still lacking something that a wobbling tower of bricks creates”

There are in fact, many ways to attempt to simulate a stacking block tower using dice, tokens, and other components. I fully admit that I find it a really interesting challenge to try to find a solution, treating it like a puzzle in itself. But by no means would any of these solutions feel the same. None of them would ever have my heart racing as I try to carefully place the next card on the table — my eyes fixed on the block tower.

All other methods would “lack something that a wobbling tower of bricks creates.”

Being simply probabilistically equivalent is not enough.

Supporting theme or just adding complexity?

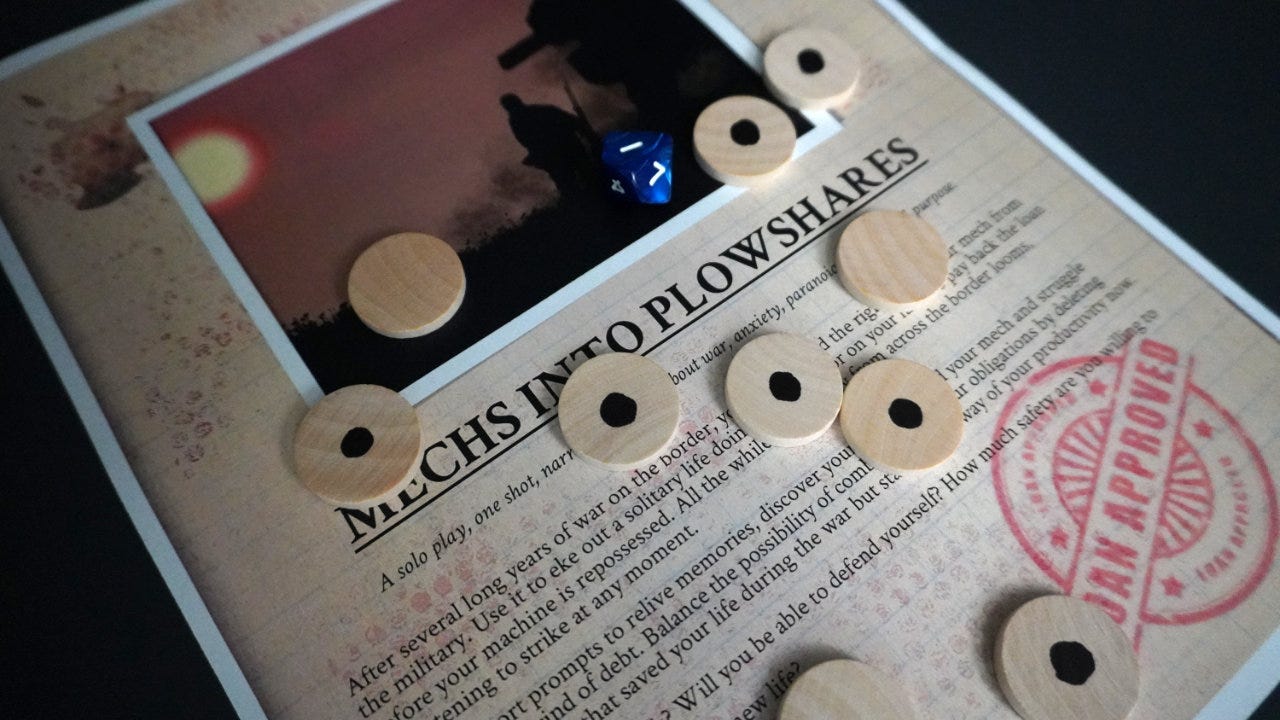

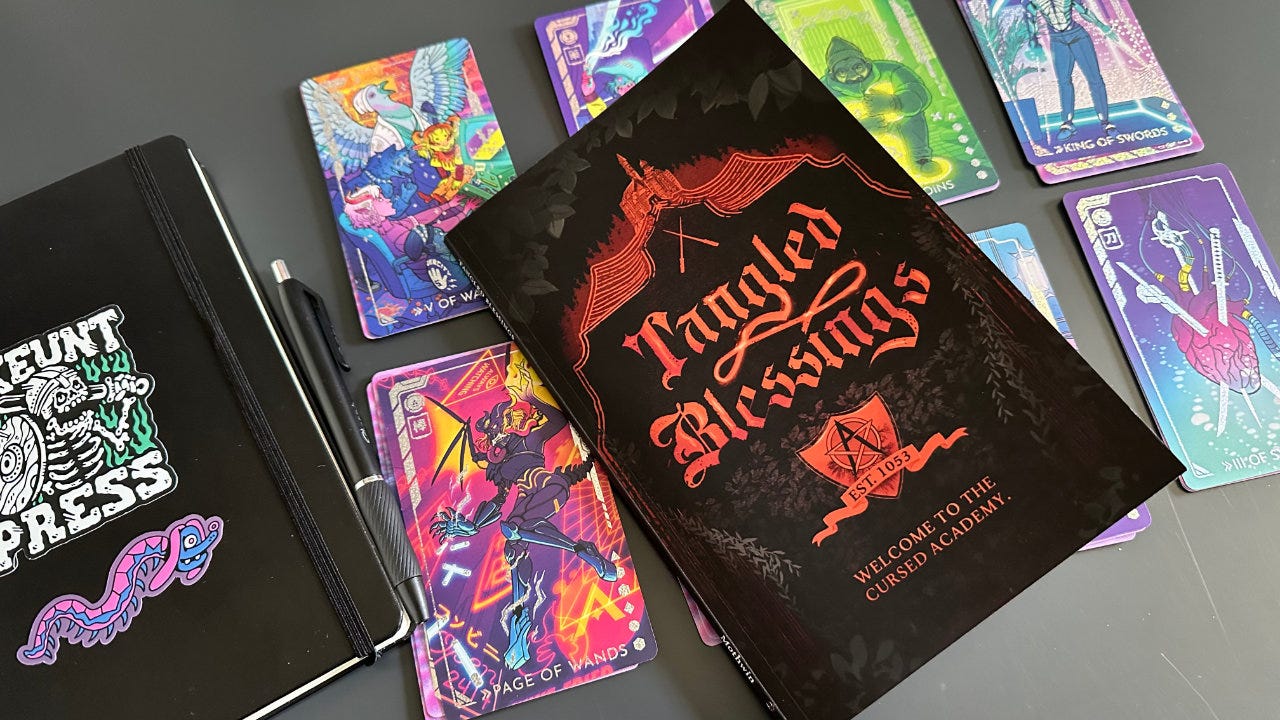

Having mechanisms that support the theme of a game is obviously important. The two examples of Ghost Beacon and The Wretched support that. I covered a third example of this while discussing Tarot Cards & Tangled Blessings back in 2023 — how it uses hidden information in pulled cards for the final exam/battle. Flipping coins while playing the Chaplain’s Game in Mechs into Plowshares might be a fourth example.

Changing these mechanism would greatly diminish the games.

There are times, however, that probabilistically equivalent mechanisms should favor the simpler option. If the mechanism is already an abstraction and doesn’t change the components, a simpler option might suffice. For example, rolling a custom d12 with only numbers 1-6 (i.e. two of each number) on it is the same as rolling 1d6.

Additionally, I’ve seen TTRPG core resolution mechanisms that didn’t really differ from simply rolling a simpler, equivalent mix of dice. I don’t think simplifying those mechanisms would have changed the feeling of the games at all.

As with most design concepts, there is no simple answer. It depends on the game, the core player promises you make, the kinds of fun you want to support, and the layers of theme you choose to use.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Probabilistically equivalent mechanisms: Learn to identify mechanisms that have identical underlying probability distributions. Think about how they support the theme. Are they critical to the theme? Would a different option do a better job of supporting the theme and narrative of the game?

Touching components: Beyond storing information, components are the way that players physically interact with games. Never underestimate how the choice of miniatures, tokens, meeples, and cards impacts the player experience.

Fixed but hidden: Even though the information may be random, having the player draw a card or otherwise lock-in that information early is more powerful than generating it at the end. Tangled Blessings is a prime example.

What do you think? What are your favorite thematic mechanisms?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want a creative boost in October? The MÖRKTOBER prompt preview was just released! Make weird stuff for 31 days next month. 🎃

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

I highly recommend Thematic Integration in Board Game Design (CRC Press, 2024) by Sarah Shipp. The concepts in the book apply not only to board games but to TTRPGs and video games as well. Her layers of theme model for thematic integration is extremely insightful.

It is generally easier to roll a die than it is to flip a coin and catch it (or have it land where you’d like). At least that’s the case for me.

I fully expect to be destroyed in the comments by actual mathematicians as I might be using this term incorrectly. From my Wikipedian knowledge of the subject, however, it certainly seems to be a fitting phrase for what I want to describe. If you are a math nerd, please share how I’m wrong and what phrase I should use instead in the comments.

You can try the one-page “micro edition” of Ghost Beacon now. Feel free to grab a community copy at no cost.

The Wretched hits the sweet spot of game duration, tension, creativity, but with enough “scaffolding” to make it easy to play for those new to the genre. Plus a giant alien that wants to eat your face.

I think there is a clear difference between drawing cards and ticking a box to say roll a die later: with a deck of cards there is a finite and distinct set of outcomes. The player will never draw a King of Hearts twice.

Whether that difference is important in your game is a whole different question.

Narratively: using a deck contributes to the feeling of discovering unique objects.

Mechanically: if you had a mechanic that let players filter or modify the deck, it would contribute to a player's feeling that they are changing their odds (even though the the change in odds may not be very large).

One of the first games I made used coin flips because I wanted to keep the game as simple as possible, and what's easier than a d2? Turns out that coin flipping is a much harder dexterity game than dice-rolling, and what's worse, coins are harder to come by in this digital age than I'd expected.