There’s a wasp crawling on your arm...

Exploring theme vs. mechanism in Inhuman Conditions

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Last week we looked at some data in the Skeleton Code Machine Annual Review.

This week we are back to games!

So, if you don’t mind, have a seat at the table. I’m going to ask you some questions, some of them personal in nature. Reaction time is a factor in this, so please pay attention. Answer as quickly as you can… as we look at Inhuman Conditions!

The Voight-Kampff Test

You know the scene from Blade Runner (1982):

Holden: You're in a desert, walking along in the sand when all of the sudden-

Leon: Is this the test now?

Holden: Yes. You're in a desert walking along in the sand when all of the sudden you look down-

Leon: What one?

Holden: What?

Leon: What desert?

Holden: It doesn't make any difference what desert, it's completely hypothetical.

The interview continues with Leon becoming increasingly agitated. It ends quite poorly for one of parties involved.

Originally featured in Philip K. Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and then in the Blade Runner film adaptation, the Voight-Kampff machine is a polygraph-like machine used to interrogate suspected replicants (i.e. robots indistinguishable from humans).

The interviewer asks questions designed to provoke an emotional response (i.e. “There’s a wasp crawling on your arm…”), and the machine measures parameters such as heart rate and eye movement. The interviewer watches for subtle differences that will reveal if the suspect is a robot.

Inhuman Conditions (Maranges & O’Brien, 2020) takes this concept and turns into a playable game.

Inhuman Conditions

Inhuman Conditions is a social deduction game for two players:

Inhuman Conditions is a five-minute, two-player game of surreal interrogation and conversational judo, set in the heart of a chilling bureaucracy. Armed only with two stamps and a topic of conversation, the Investigator must figure out whether the Suspect is a Human or a Robot. Robots must answer the Investigator's questions without arousing suspicion, but are hampered by some specific malfunction in their ability to converse.

At is core, it’s a simple game: the Investigator asks the Suspect questions for five minutes and then makes a guess if they are a robot or not.

This gets mechanically more complicated by the following twists:

There are multiple interview Modules to choose from ranging from Small Talk to Threat Assessment and Creative Problem Solving.

The suspect assumes a particular random Background role from a deck of cards (e.g. “former child star” or “disgraced scientist”).

If the suspect is a robot, they are either:

Patient: They have a unique rule they must follow during the interview, such as “You may only talk about facts and never opinions.”

Violent: No restrictions, but they must complete two of three secret objectives. If they do, they slam theirs hands on the table and kill the Investigator.

If the suspect ever fails to abide by their rules, they must do the Penalty task which is known to both parties. This could be “say any three letters in a row” or “use an ordinal number other than first”.

After the five minutes, the game ends in one of the following outcomes:

Investigator guesses human and the Suspect is a human, they both win.

Investigator guesses robot and the Suspect is human, they both lose.

Investigator guesses human and the Suspect is a robot, the robot wins.

Investigator guesses robot and the Suspect is a robot, the Investigator wins.

While the scenario where the Suspect is indeed a human might be the least interesting of the options, it’s the uncertainty of each round that adds excitement to the game.

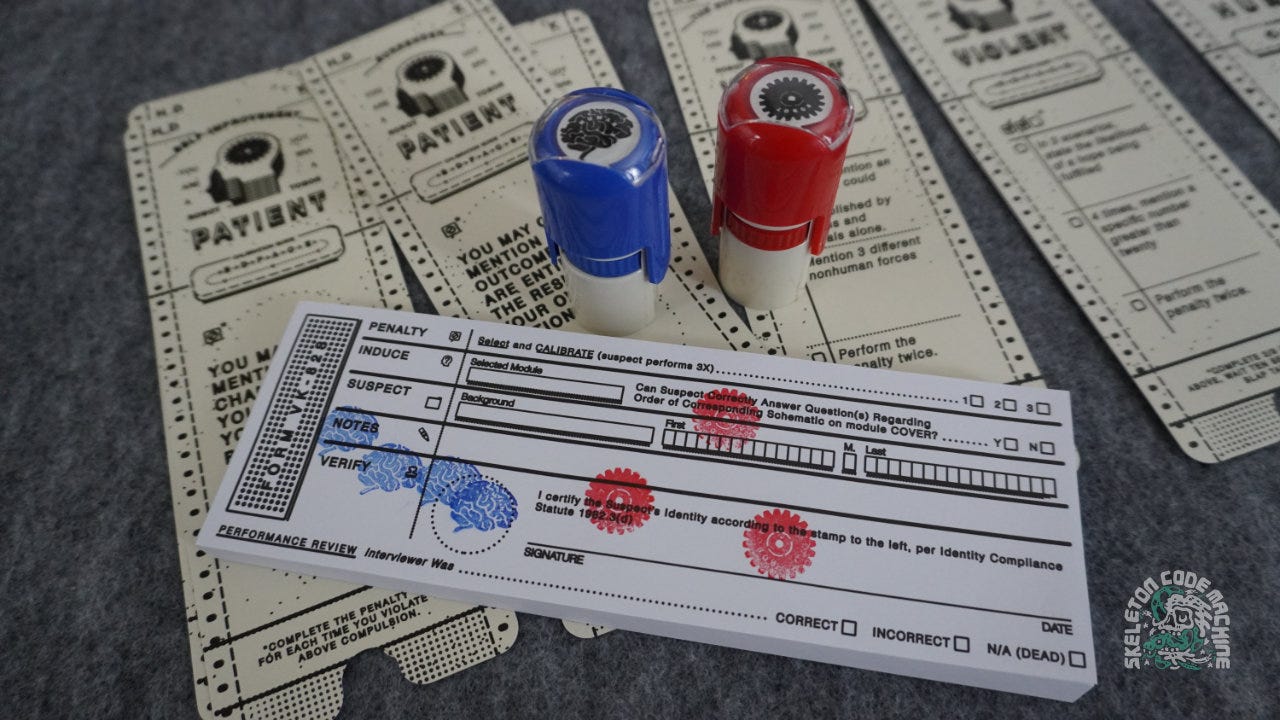

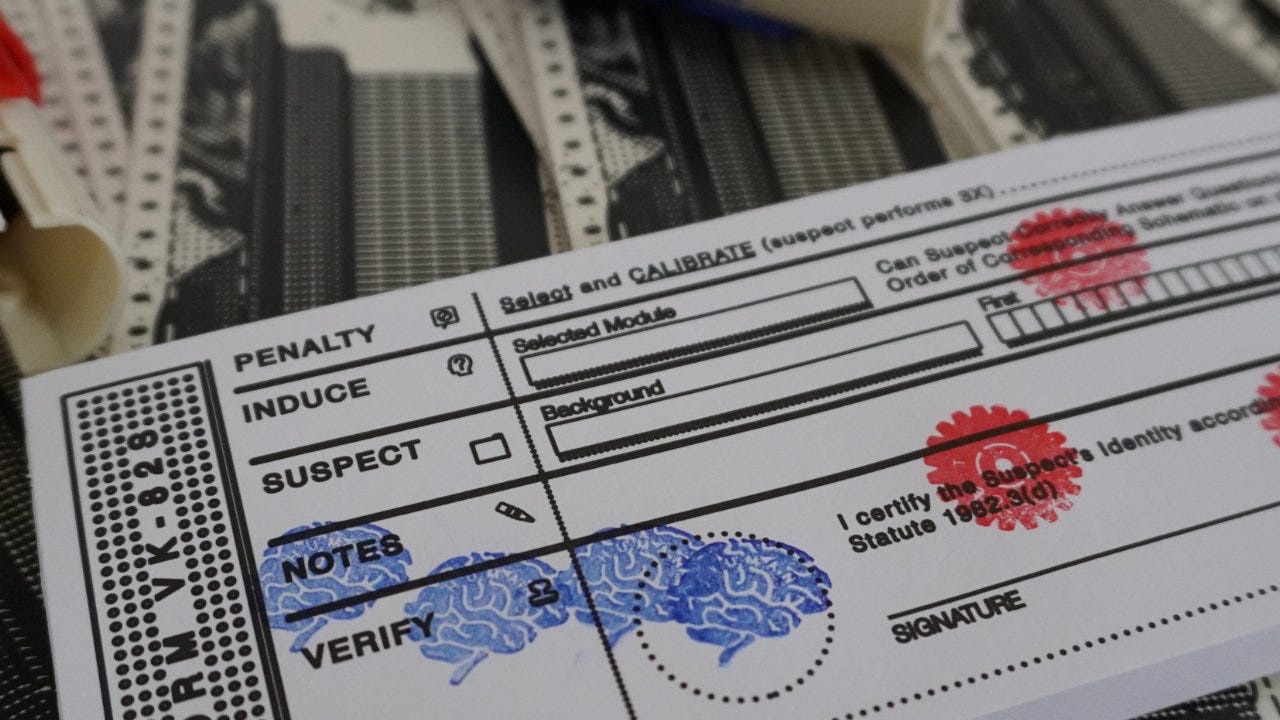

Punch cards and stamps

The production of Inhuman Conditions is impressive. Every component fits the theme of the game. Even the rules mix instruction with theme, describing how to perform the Intake Procedure, Administer the Inducer, and perform the Interference Task.

The cards are shaped like punch cards, the notepad is sufficiently bureaucratic, and two stamps are included to finalize the paperwork.

While this game could have been produced as a TTRPG zine (and there is indeed a print and play version), it’s hard to deny that all these bits make it more fun to play!

Intake Process

An interesting part of the game is the Calibration procedure performed before starting the questioning. Mechanically, it’s trivial:

Players agree on a Penalty task (e.g. “Say any three letters in a row.”)

The Investigator asks the Suspect to perform the Penalty task three times in a row.

The Suspect then performs the task three times.

At first glance this might seem pointless, but the rules insist, “Calibration isn’t just a formality! It serves two essential purposes…” One reason is to remove ambiguity about the penalty if there is confusion or disagreement about what it means.

The other reason is perhaps more interesting:

It’s the first time the Investigator has an opportunity to establish authority. The interrogation will go better if you take this opportunity to be firm and clear with your directions.

Taking this part of the game seriously sets the tone for the rest of the game. Setting the tone and the scene for interrogation matters when it will only last five minutes.

While this sort of prelude might seem out of place in a board game (Tom wasn’t a fan), it is quite common in roleplaying games.

It made me think about theme vs. mechanisms…

Theme vs. mechanism

When trying to demonstrate the importance of thematic elements in tabletop games, I often use the example of Risk (Lamorisse & Levin, 1959). It’s a game everyone knows, many people have played, and has had countless reskins and editions over the years.

It’s hard to deny that while the mechanisms are appealing, the theme is a significant driver for Risk. Stripped of all theme, the game could look something like the abstract network graph above. I doubt that would sell as well as the latest Lord of the Rings Risk or Warhammer Risk edition of the game!

Taken purely as a mechanical game, Inhuman Conditions could also be stripped down to it’s bare components. There might not be much left after removing all theme! Does that mean it’s not a good game? Absolutely not! It’s that mixture of mechanism and theme that makes it so appealing.

In many cases, it’s the theme that allows players to build stories and artifacts of play that last after the game ends. Capturing four pink dots isn’t nearly as memorable as that time you won because you captured Australia at the end of the game!

Board game vs. TTRPG

This consideration of theme and mechanism leads to a broader discussion of the difference between board games and tabletop roleplaying games. Inhuman Conditions in interesting because it did both of the following:

Nominated for the Best RPG Related Product ENNIE Award

Maintains a 7.0+ rating on BoardGameGeek

Usually those two achievements are mutually exclusive, with games being tossed into either the TTRPG bucket or the Board Game bucket. Rarely does one do both!

Games that blur the line between board game and TTRPG are exceptionally interesting to me, but can be hard to find. They need extremely strong thematic elements, but they also need solid mechanical structure. The King’s Dilemma (Hach & Silva, 2019) and Call to Adventure (O’Neal & O’Neal, 2019) are two examples that come to mind.

How players react to this mix of theme and mechanism depends on player motivations and the type of fun they are hoping to have.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Theme vs. mechanism: Consider both thematic and mechanical elements when designing games. A fun exercise is to try playtesting your game stripped of all theme and see how it holds up!

Board games vs. TTRPGs: Board games become more like TTRPGs when they build stories that redirect players away from simply trying to win. TTRPGs become more like board games when they try new and unique mechanical elements. Consider how to blend the two, and make games that are harder to define.

Jack of all trades: Designing games in the space between board games and TTRPGs can be tough! There is a risk when trying to appeal to different groups that you’ll end up appealing to neither, landing in some sort of uncanny valley of gaming.

While I generally think the concepts of “board game” versus “roleplaying game” are on a spectrum, I’m still going to give just two options in this week’s poll! Is Inhuman Conditions a board game or is it a TTRPG?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. The Dead Horse horror anthology is available now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🐎

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

As an autistic person, I've never understood that test scene. And I wonder if it's like that for everyone, or just me? Anyway, the idea of this game sounds really intriguing but I'm pretty sure it would be upsetting for me.

Adding the Risk map was a really clear example of theme vs mechanics, I'd never looked at it like that before! Would you say this is similar to putting out an SRD (just mechanics, no theme) rather than a game (theme + mechanics) ?

Brilliant game!! Glad you covered it; a fine example of how the lines between "TTRPG" and "board game" are blurry and changeable.