Storing information with components

Exploring how much information is stored in a deck of cards.

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

With the 2024 One-Page RPG Jam in full swing, I’ve been working on the Exeunt Press game that will be submitted. It’s a solo journaling game, but with some interesting mechanical restrictions in how the prompts are chosen.

Designing the game really had me thinking about how to compress game mechanisms into a limited space and use just a few components.

What’s in a deck of cards?

A standard 52-card deck has 13 ranks in 4 suits: clubs (♣), diamonds (♦), hearts (♥) and spades (♠). When used for representing information in a game there are two things you can use:

Rank (value)

Suit

When each card’s rank and suit are combined into a unique identifier, it gives you 52 different bits of information. This can be easily used to randomize selections from a list. For example, draw a card to determine which of 52 treasures a player might find.

Splitting the rank and suit, you get four sets of 13 unique cards in each suit. Those sets can be used to represent categories in a game. Eleventh Beast uses this method:

Hearts: The Beast’s physical appearance

Diamonds: The Beast’s behavior

Spades: Wards and protections from the Beast

Clubs: Weapons and tactics against the Beast

Similarly, the cards could be divided by color instead of suit: black (clubs/spades) vs. red (hearts/diamonds). This would give you two decks of 26 cards each.

The court cards (face cards) in a standard deck are the King, Queen, and Jack. There is also an Ace card. They can either be treated as a rank (e.g. Ace is 1, Jack is 11, Queen is 12, etc.) using only their value, or they be used for special events depending on the game.

There are many ways to use the cards and the information they contain. Ultimately, however, they store just two bits of information: rank and suit.

Or do they…

Storing more information in a card

If you consider each card in physical space on a table, you’ll discover cards actually store3 more than just those two bits of data.

The way the card is positioned on the table can be used to store information as well, beyond the card’s rank and suit.

The prime example of this is “tapping” a card in Magic: The Gathering (Garfield, 1993). As cards are played onto the table, they are upright (i.e. readable) relative to the card’s player. Actions in the game will cause cards to be “tapped” meaning they are turned 90 degrees from the upright position. Tapping indicates they have been used or exhausted.1

Various positions mean each card has quite a bit more information storage capacity:

Rotation

Face up vs. face down

Touching or covering other cards

Deck or pile size

In addition, cards have a “memory” where dice usually do not. This means that once a card is drawn and put in a discard pile, you won’t draw the same card again. This is yet another bit of information that can be stored. You could make the argument that this is positional information because it is the location of the card (i.e. draw or discard pile) that determines if it has been drawn or not.

Now if we consider rank, suit, court cards, aces, and physical position all together, we can store far more information than we might have guessed.

What about dice?

At first glance you might think dice store only one bit of information: value. Sure, there are various polyhedral dice types (e.g. d6, d12, d20, etc.) but they all just yield one value when rolled.

Actually, some of these same ideas from the card example can be applied to dice:

Dice value (face)

Dice color (black and white are common)

Dice position on the table

Sum of the values (or other arithmetic)

Games that rely on d66 tables or similar systems will often use two different color dice so the player knows which one is the first digit vs. the second. Here’s how RPG Museum describes it:

A d66 is a type of dice pool that includes two separately identifiable d6s, in which the result is determined by taking the result of one d6 as the tens place of a number (i.e. the numeral on the face multiplied by ten) and the result of the other d6 as the units place. (This is similar to the way two d10s can be used to simulate a d100.) This gives 36 equally possible outcomes between 11 and 66, in which the only digits are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6.

With just two dice you can get up to 36 different combinations, rather than just the expected 12. The zine edition of Exclusion Zone Botanist uses this method when discovering new plants. Black and white dice are recommended.

Dice drop mechanisms

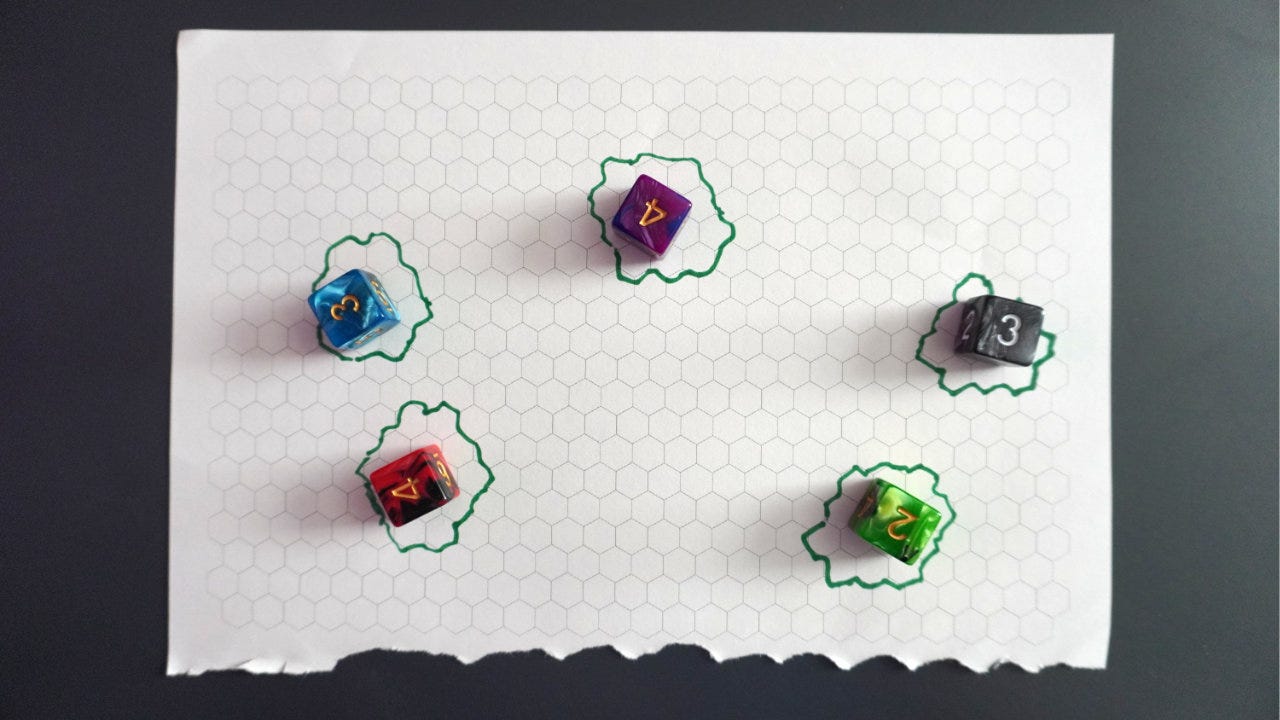

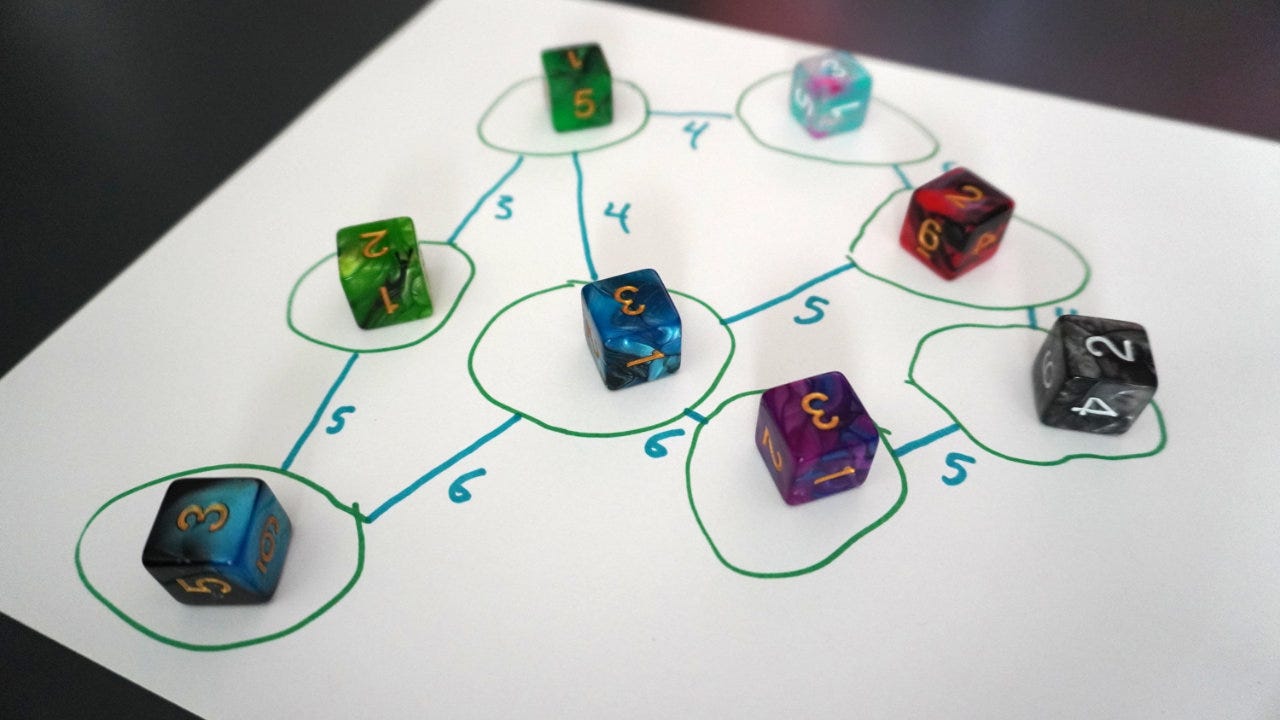

Dice drop mechanisms used in TTRPGs are a great example of positional information. Dice are dropped onto a map, table, or blank sheet of paper. It is a combination of the value and the position that determine how to interpret the results.

In Across These Endless Skies by Mitchell Daily, this method is used to create a map:

To create the islands in your section of the Endless Skies, take a handful of d4s (at least 4) and drop them on a table or a piece of paper. Feel free to prod them into a satisfying spread and record them. The number on the die determines the location’s population value.

The islands are then connected and the values summed to determine the traffic rating of a route. For example, connecting a 1 and 4 would mean the connection between them would be a 5. It’s an interesting use of limited components that store a lot of information.

Many similar dice drop map methods use a hex grid when dropping the dice. This is a quick way to build an overland map for a campaign, or could be used as a core mechanism within a worldbuilding game.

There are some really interesting uses of the die drop mechanism in Riverbend: Fishing Adventures by Gustavo Tertoleone and Victor Amorim. Not only is it used for creating river basin maps, it’s also used for fishing:

While in a Fishing Spot, PCs may attempt to catch fish dropping dice on the Fishing Die Drop Table (inside front and back covers) according to the Fishing Equipment used. This roll determines the type of fish hooked and the number of potential catches. Details on dice used by each equipment can be found on the equipment session.

The covers are illustrated fish with outlines. Dropping dice onto them determines which ones may be caught.

How much information can you store?

The obvious solution to storing more information is to use custom components. Once you begin manufacturing custom cards, dice, and tokens for your game, the options are limitless. The challenge is, however, that the production costs go up significantly once custom components enter the design.

Take a look at any of the games from Button Shy and you can see some of the amazing things they accomplish with just 18 cards.

Assuming you aren’t going the custom route, I think it’s interesting to consider how much information is stored in each component. It’s a different way of thinking about the physical production of games, and could help reduce the cost and size of a game.

When making a one-page roleplaying game, understanding how much information is stored in each component becomes critical. Space and components are limited, so figuring out how to store more bits in a card is extremely useful.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Think of components as information storage: It might seem like an odd way to think about a miniature or some d6 dice, but it might unlock some new ideas. Try to combine value, position, color, size, and other features in interesting ways.2

Limited space sparks creativity: If you caught last week’s Make your own one-page RPG series, you know that it is restrictions that help to generate new ideas. Multi-use components are necessary tools in restricted designs.

You should design a tiny game: The One-Page RPG Jam is a great way to try your hand at game design. Even if you consider yourself a “boardgamer” only, you can still give it a try. Many of the RPG entries feel very much like boardgames!

What do you think? Have you seen discussions of this topic before? Is it helpful to think about components as information storage?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Grab a copy of Make Your Own One-Page Roleplaying Game by Exeunt Press. It’s just $5 and walks you through the process from concept to publication.

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Wizards of the Coast LLC has an expired patent US5662332A for “a novel method of game play and game components that in one embodiment are in the form of trading cards.” This includes tapping energy elements when used by a command element in games. Whether or not this actually prevented other companies from using the term “tap” is much debated online. I’m not an IP lawyer, so your guess is as good as mine.

Be careful when using color as an indicator in tabletop games. Use Ian Hamilton’s three principles: (1) Don’t use color difference alone, (2) Check your colors with a simulator, and (3) Run it by some people to test it. This is a complicated and deeply interesting topic that deserves its own Skeleton Code Machine article.

Im using a coin for my one page game. Now Im not using it the standard a/b or the bit 1/0 way. I think I got my mechanism from school/work when I used a pair of 4 bit outputs to control 100 relays a la battleship.

So basically 2 flips work as a d3, 3 flips d6, 4 a d12, but Im only using the d3 and d6 for the easy mode of the game

…or you can get a d6 to play it.

Great information