Fair (and fairy) cake-cutting in Pacts

Exploring how the divide and choose ("I cut. You choose.") mechanism in Pacts from DVC combines with area control to create tough choices and meaningful decisions.

I’m back from PAX Unplugged, resting up and hydrating. It’s always the best event filled with games, meeting new and old friends, so much walking, soup dumplings, and never enough time to do everything I’d hoped. Thank you so much to all the Skeleton Code Machine readers who took the time to say hi and chat with me!

Last week (which seems like forever ago), we looked at a game published over forty years ago — SPI’s Dragonslayer movie-based fantasy game. Specifically we explored the idea of prep vs. combat and some ways we might modernize the design.

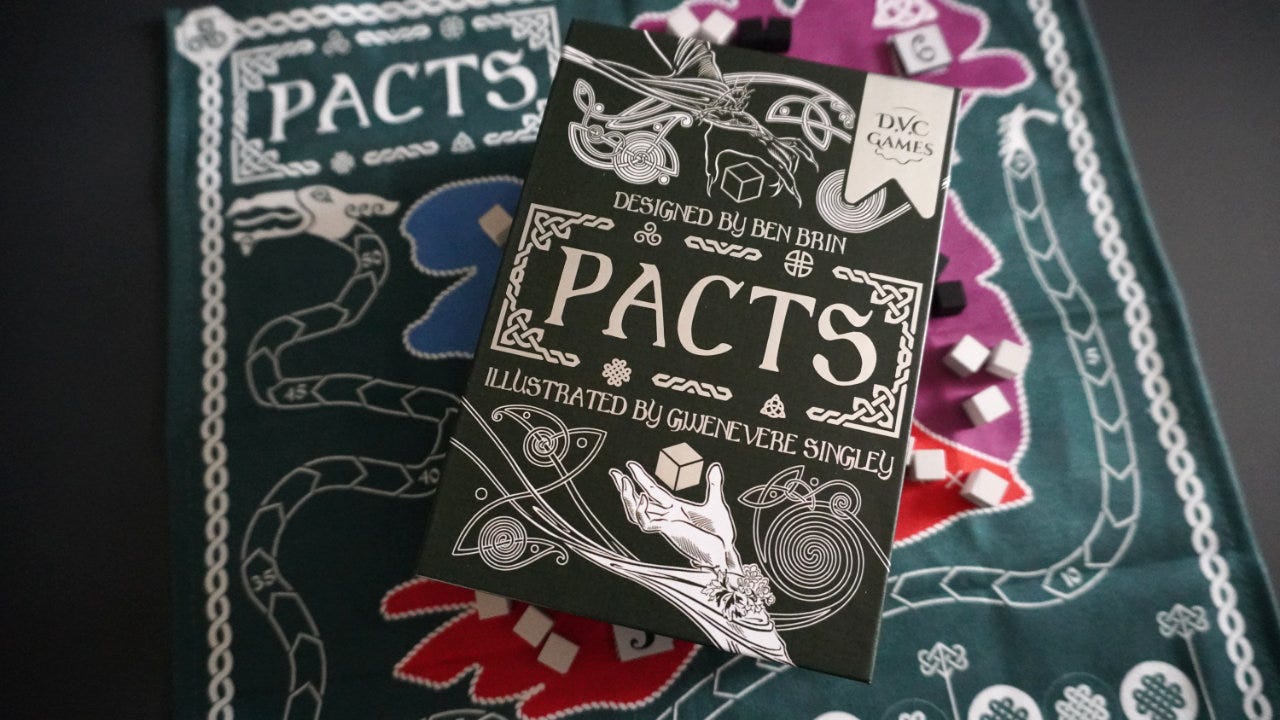

This week we are looking at a game published this year by DVC and featured at PAXU — the faefolk-themed Pacts by Ben Brin.1

Pacts

Pacts (Brin, 2025) is an area control game about two dueling Celtic faefolk (fairy) factions (Seelie and Unseelie) vying for control of the land:

“You will each place, move, and remove influence across six regions and see who rules these sacred places, seeking majority control. The player who scores the best after three and six rounds will be declared the new ruler of this great isle.”

While DVC might be known for quirky games like Signal (Beatrix, 2025), Pacts plays more like a mechanical board game — choose a court card, draw and split some pact cards, and resolve all of your actions.2 Actions are mostly placing or moving cubes representing influence in the six regions. There are also special variable player powers that can be used by each side.

It is not a complex game (the rulebook is just a few small pages) but it is a fascinating one. In particular, the splitting and selecting of pacts might be the best part of the game. It’s a perfect distillation and example of a “I cut. You choose.” mechanism.

Let’s dig into that part of the game…

Fair division optimization problems

In game theory (i.e. using mathematical models for strategic interactions), fair division is one of the optimization problems that arises. It describes when multiple parties are all entitled to a limited resource and need to divide it in a way that is agreeable to everyone involved. It’s a broad class of problem, including cases where items can be distributed, divided, or assigned between two or more parties.

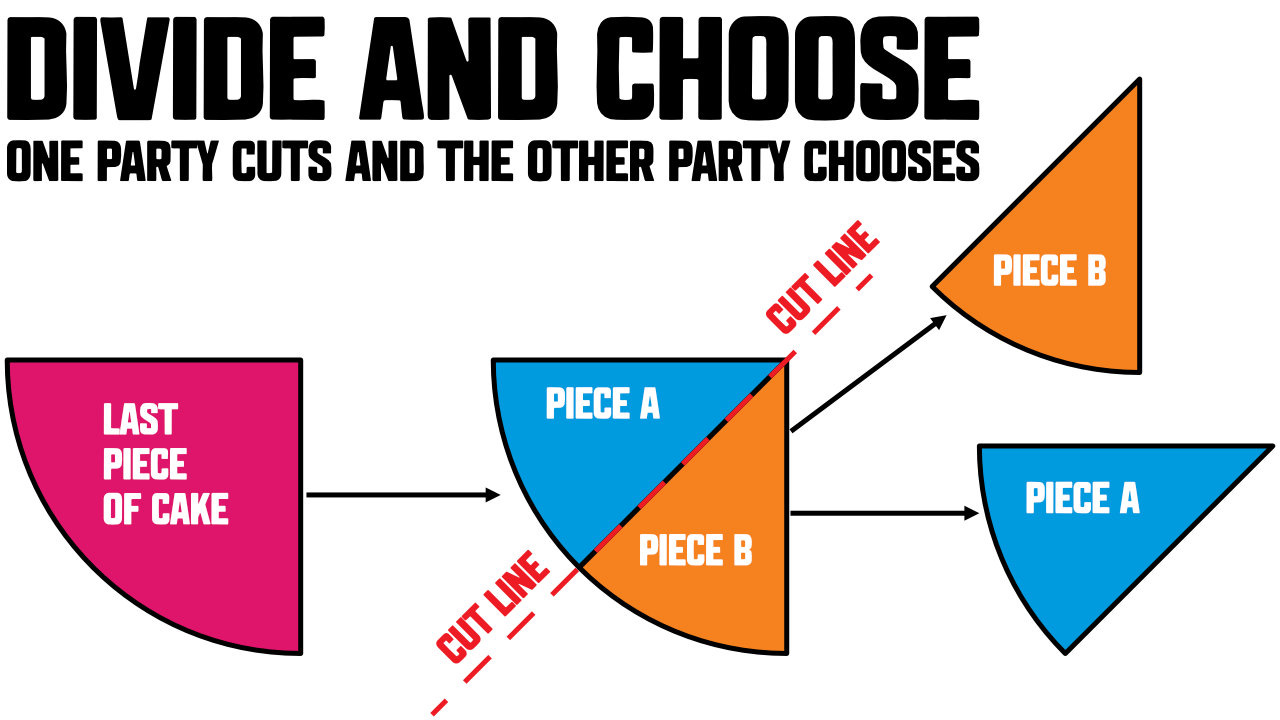

The most famous example of the fair division problem is divide and choose, which is a way to equitably divide a limited resource between just two parties.

The classic illustration of this is cake cutting, familiar to anyone with siblings:

There’s only one piece of cake left, and two people would like some of it. As a solution involving fair division of a resource (i.e. the cake), one person (i.e. the cutter) cuts the cake, dividing it into two approximately equal pieces. The other person (i.e. the non-cutter) selects which piece they’d like first.

This solution creates an incentive for the person cutting the cake to divide it into two approximately equal pieces. If they cut in an unequal manner (i.e. one big piece and one little piece), the non-cutter will take the big piece, leaving them with the small one. Both parties have agency and act according to their desires, but the result is usually one that is equitable for both.3

I cut. You choose.

In tabletop board games, this method is often called “I Cut, You Choose.”4 It shows up in many games and with many variations.5

The Great Split (Hack & Silva, 2022) uses this method explicitly by having one player divide cards into two groups and another player choose. In Tussie Mussie (Hargrave, 2019), the player draws two cards and decides which to offer to their opponent face up and which to offer face down. The opponent selects one of the two cards, known or unknown.

In Pacts, each round one player will draw five pact cards and divide them into two piles of their choosing. In addition, they will also add a 2nd Player token to one of the piles, increasing the desirability of the pile — there’s an advantage to going second. Then the other player will choose one of the piles. Finally both players will resolve their actions — 1st player and then 2nd player order.

If this were a simple fair cake-cutting example, the cutting player would simply try to make two piles of equal value, as valued by both players.6

But it’s more interesting than that.

Unequal piles of unequal value

As mentioned above, Pacts is an area control game. Players are ultimately trying to place their colored cubes into six areas (regions) on the map for the three scoring phases of the game. It’s simply majority — have more cubes and get the points. It’s winner takes all with no second place.7

The cards can be hard to value, particularly when some cards can be used to activate the player’s special ability:

Sometimes it’s important to deny the other player the card that lets them use their ability. So the pile with the ability-triggering card needs to be very poor.

Other times, it makes sense to balance the number of cubes that can be placed between the piles.

Still others, it might be important to deny cube movement but ceding some cube placement cards is acceptable.

It’s a mixture of abilities, timing, movement, and placement.

All of this means the piles are rarely of equal size or value. Instead they have different values for each player. One card might be of significant value to one player who needs it (e.g. ability-triggering card) but of little value to the other.

At no point is it as simple as dividing a piece of cake into two equal slices so your brother doesn’t get more than you.

Reusing old mechanisms

The divide and choose has a long history, spanning thousands of years.8 Yet it is possible to take it, tweak the inputs to it a little bit, and end up with a tabletop game mechanism that feels fresh and novel. It’s not unlike how Arcs (Wehrle, 2024) uses trick-taking as a mechanism but it is not a trick-taking game.

I think it’s interesting that the fundamental divide and choose part is still there — splitting things into two piles. But it’s the heterogeneous nature of the limited resource and different per-player valuations that make the splitting and choosing hard, often painful, choices.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

More area control please: I personally love area control games. I keep thinking that at some point I’ll own enough of them or get bored with them. Yet there seem to be an infinite number of ways to make them feel new and interesting. It is fertile ground for game development.

Old mechanisms made new: Divide and choose (“I cut. You choose.”) is thousands of years old, but doesn’t need to be boring. It is simple (i.e. easy to explain) and at the same time can be interesting.

Small box, simple components: DVC is doing some interesting things with small box games that aren’t much more than cloth boards, cubes, and cards. I love my big box of plastic games, but more and more I’m interested in games that set up quickly and fit in my backpack.

What do you think? What are some “I cut. You choose” games that you’ve played or enjoy? Do you think the mechanism can stay fresh and interesting?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want more in-depth and playable Skeleton Code Machine content? Subscribe to Tumulus and get four quarterly, print-only issues packed with game design inspiration at 33% off list price. Limited back issues available. 🩻

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

As always, SCM posts are not game reviews. That said, it would be hard to disguise my love for Pacts. It’s already being called the game of the con and I’d agree.

For more about Signal, check out the SCM article on inductive reasoning games.

The issues of fair division, divide and choose, and fair cake-cutting are actually highly complex topics and the subject of intensive study and analysis. Methods have been around since at least the earliest writings we have and it’s still not a completely solved problem. See also: veil of ignorance.

In many places, including BGG, this mechanism is written as “I Cut, You Choose” with capital letters and just a comma between the two phrases. That seems really odd to me, because they are stand-alone sentences with no conjunction. I could maybe accept a semi-colon (;) between them, because sometimes that is used as an implied conjunction. The alternative is calling it “divide and choose.” Either way, I’m not an expert in grammar and get to choose how I write it. I’ll be using “I cut. You choose” throughout the article. Send complaints to murphdog@exeunt.press, but make sure you also tell her she’s a good girl.

The most popular example on BGG is Castles of Mad King Ludwig (Alspach, 2014), but I don’t have any direct experience with that game. I know people really enjoy it.

This assumes a homogeneous cake — one in which every slice would have identical ingredients. This becomes harder when it is heterogeneous. Imagine a cake with icing flowers or strawberries.

On a tie, no points are scored by either party.

Check out the History section of the Wikipedia divide and choose article. For examples ranging from the Bible, to medieval literature, to the modern UN.

a fascinating read as always :D love the themeing of the game, and the central "I cut. You choose" mechanism seems just beautiful, reading your description even gave me the chills ^^ (incidentally, i first wrote "gave me" as "game", which would have been a really fun association-based typo ^^) the odd number of cards, the one second-player token, and then all the different kinds of things different cards can allow you to do... just beautiful :) i also do love a good hard choice – probably part of why i love PbtA and related 'schools' of games, for their move outcome choice lists and/or character creation picklists :)

Tussie Mussie is one of my favorite versions of this simple, elegant mechanic. Hargrave spoke about how she came to write it at last year's PAX. Everything Button Shy does is so cool. Sorry I missed you, I coulda used a free sticker lol