Revisiting SPI's 1981 Dragonslayer and what it can teach us

What can we learn from the board game adaptation of the 1981 dark fantasy film Dragonslayer? Quite a bit, both from what it does well and how it might be adapted to a more modern design style.

Last week we were using blackjack to raise the dead and this week I’m getting ready to go to PAX Unplugged (PAXU) in Philadelphia. This week we are looking at an older game — Dragonslayer from SPI!

But first, two important updates…

Exeunt Press games & self-pub meetup: I won’t have a booth at PAXU, but you can pick up Exeunt Press games at the Indie Press Revolution Booth #3701.1 Also, if you are a self-publishing game designer and want to see my skeleton covered in meat, I’m going to try to be at the Self-Pub Meetup hosted by TTRPGkids.

Take the Skirmish Week survey: Skirmish Week is coming! Prepare for a week of Skeleton Code Machine posts all about skirmish games. I’m by no means a skirmish expert, so I’ll be learning along with you as we explore different games. Please take this short Skirmish Week Survey about which games you’d like to see featured.2 You can also weigh in on the defining features of a skirmish game.

Disney’s (very) dark fantasy film

Imagine Walt Disney producing an extremely dark and grim fantasy film packed with mud and violence. Young virgins chained to posts and being sacrificed to a dragon.3 People stabbed by Peter MacNicol and slowly dying. A wizard gets blasted with fire and explodes. And a rather nasty scene of a young Emperor Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid) being incinerated.

Well, that’s exactly what Dragonslayer (1981) was!

Urland is terrorized by the dragon Vermithrax Pejorative. The corrupt King Casiodorus keeps the beast at bay by holding lotteries to select and sacrifice girls from the surrounding villages. Galen, a young wizard’s apprentice, is tasked with slaying the dragon. There are magic spears, dragon scale shields, and many of the other tropes you’d expect.

The special effects by Industrial Light and Magic still look good by today’s standards, but the movie bombed at the box office.4 Still, with some positive reviews and the power of Paramount and Disney behind it, there was a novel, comics, and the Dragonslayer (Hessel & Simonsen, 1981) board game produced by Simulations Publications, Inc. (SPI) which was one of the top wargaming companies of the era.5

Dragonslayer board game adaptation

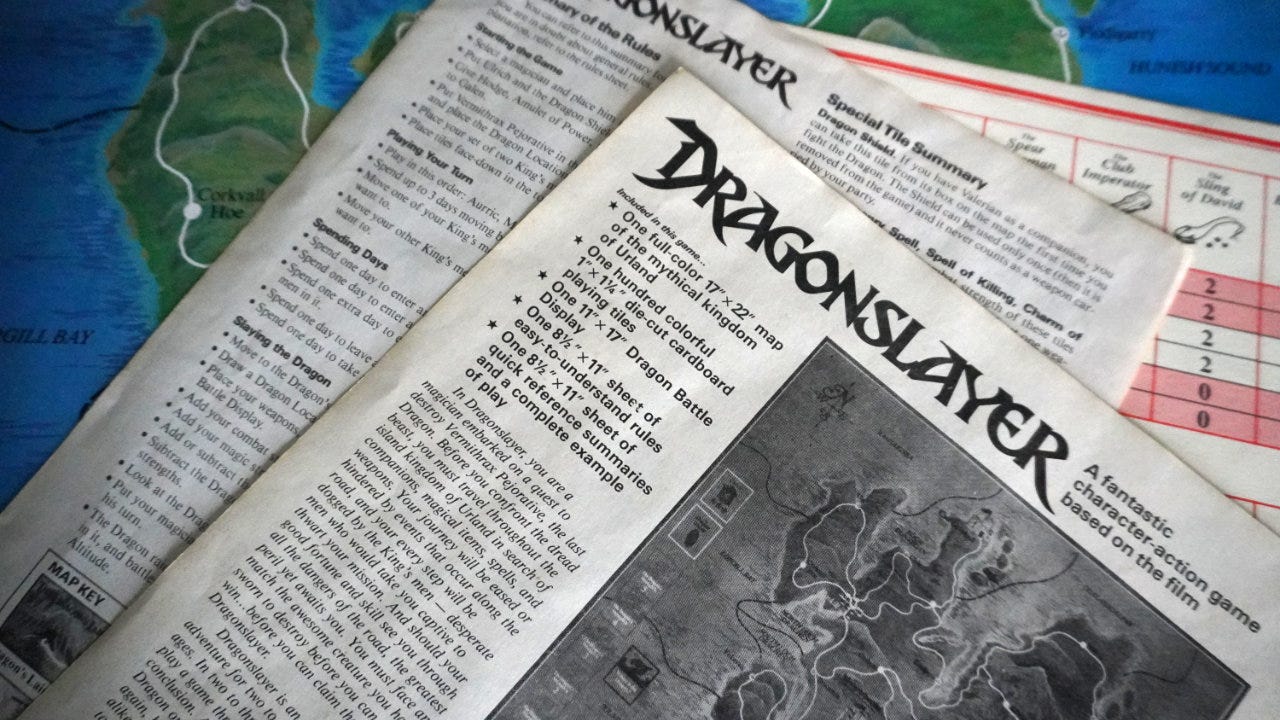

SPI’s ads at the time said, “Dragonslayer is designed to appeal to knowledgeable fantasy adventure game players while at the same time remaining accessible to new gamers.”6 That’s pretty accurate. The rules easily fit on one sheet of paper (front and back) and are summarized on another single page. There’s even a short, separate example of play, common in wargames.

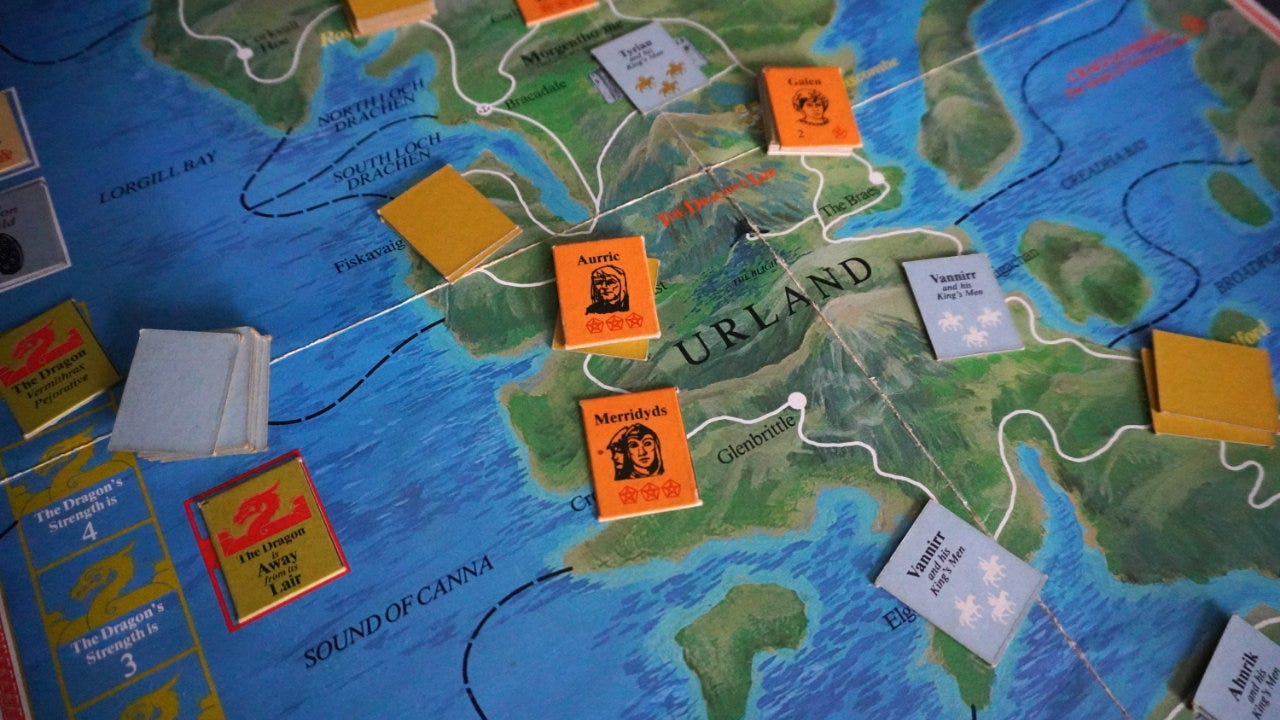

Players take on the roles of one of four available magicians (Galen, Merridyds, Old Kyvin, and Aurric), traveling around a map of Urland. Hamlets and towns have small tiles (face down) that contain weapons, magic items, or game effects. Each turn, players can take three actions (called “days” in the game) which usually involve moving to a location, collecting the tile, and moving to the next location.7

Eventually, after collecting enough “power ups” in the form of companions and equipment, a player may choose to fight the dragon.

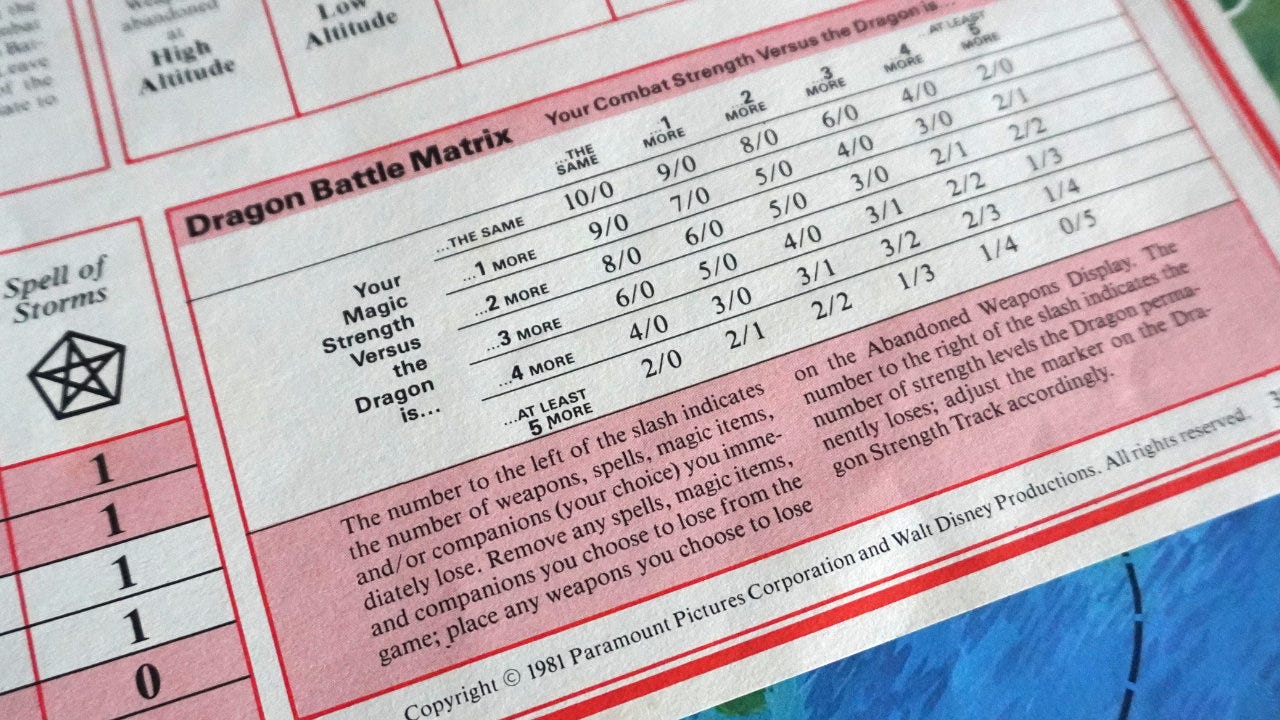

In an interesting twist, there are no dice in Dragonslayer. Instead, the dragon battles are almost entirely deterministic:

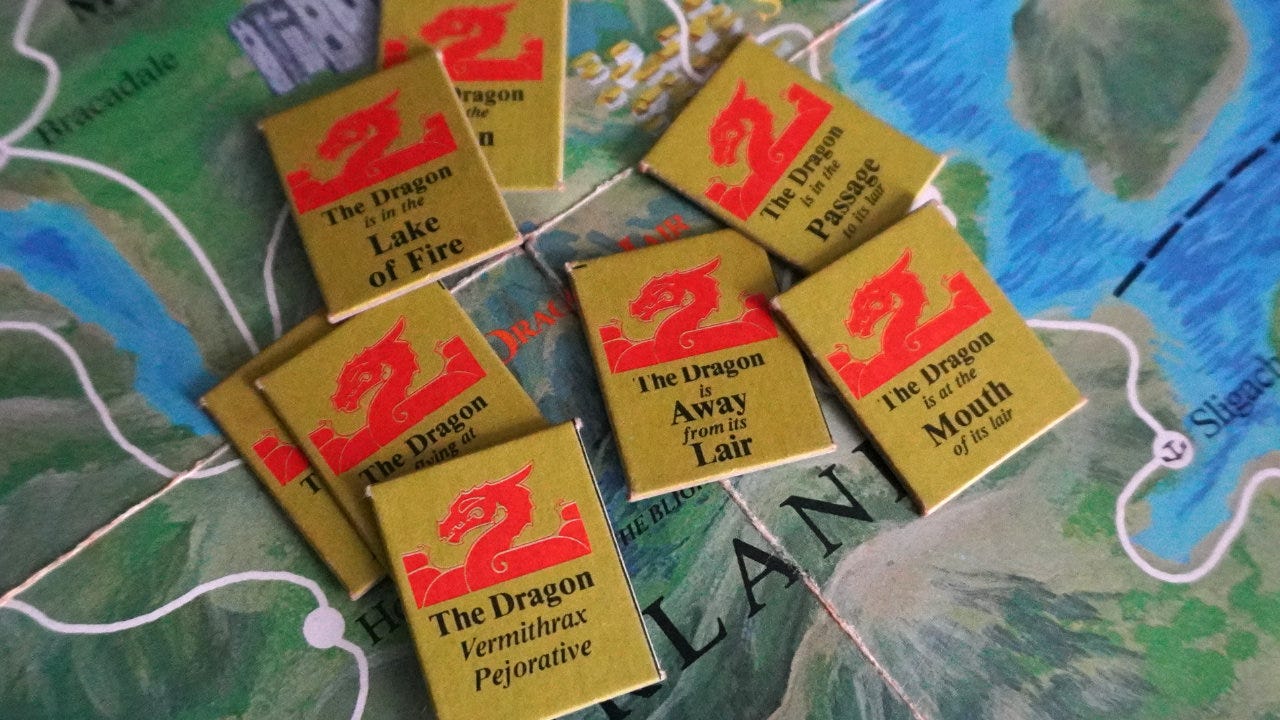

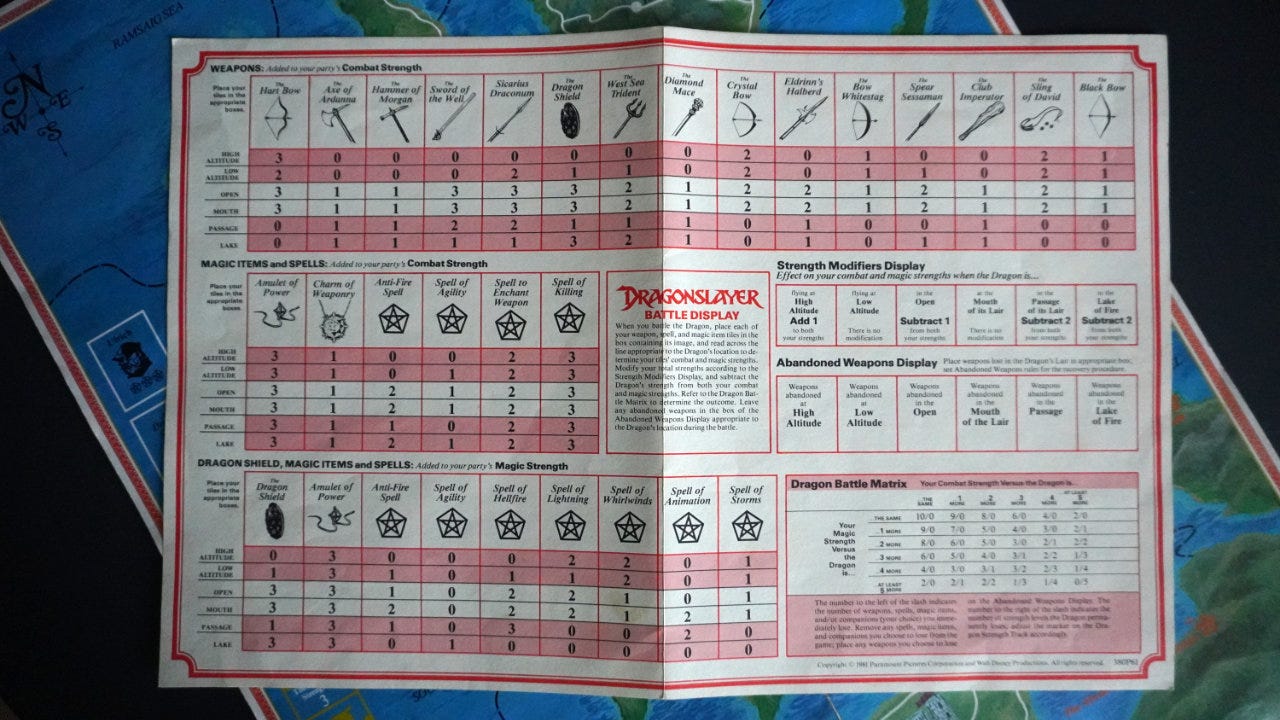

Draw a tile to determine the Dragon’s location (e.g. high altitude, low altitude, mouth of the lair, in a lair passage, etc.).

Weapons and helpful items are placed on a Battle Display mat.

Combat and magic values are calculated based on the dragon’s location and the type of items being used. Then are cross referenced on a combat results table, because this is an SPI game.

The results determine how many items and companions are lost and if the magician survives the battle.8

It’s a competitive game, so the first player to slay the dragon (i.e. reducing its strength from 5 to 0) is the winner. It is possible for no players to win and everyone lose if all magicians are killed.

Prep vs. combat

It was interesting that the game focuses on preparation for combat rather than the combat itself. This is an idea I explicitly wanted to try in Eleventh Beast, and one that I think works really well.

Players spend most of the game traveling to locations and collecting items for use at the end of the game. There are 58 tiles placed out on the board across the four towns and 21 hamlets.9 You might pick up a companion like Harald of Swanscombe or Cedric of Culnakask who add to your combat power. Alternatively, you might reveal a tile to find it says “Betrayed” (lose your next turn) or “Item stolen” (lose an item).

The players choose when to fight the dragon, knowing that it would be folly to start the battle too early. The game is a race to prepare and attempts to build tension using a self-set threshold of what is “enough” equipment.

Granted, one of the location tiles is “The Dragon is Away from its Lair” which means the dragon isn’t home right now and you need to come back later. A rather anticlimactic result of an attempted battle.

What if we changed a few things?

This is not a review of Dragonslayer or even a full explanation of the rules, but it is an interesting game worth analyzing. The game does, admittedly, use what we’d now consider outdated mechanisms like player elimination, losing turns, and low-agency tile reveals. But I keep thinking that the core of the game is solid and could inspire new designs with some tweaks:

Reasons to travel: Adding a reason to go to specific locations would help this game considerably. Currently there’s almost no reason to go to one hamlet vs. another because all the tiles are hidden and of equal probability (i.e. false choice). If specific locations had a greater or lesser chance to provide specific items, there would be a reason to travel one way vs. another.

Player objectives: If specific types of items could be targeted (magic vs. combat), player characters could have “build paths” or personal quests and objectives. This would differentiate the characters and give more reason to both travel to a location and/or block an opponent from a travel path.

Dragon location: Attempting to fight the dragon only to find it isn’t home can be pretty disheartening. Adding some amount of probability or predictability to its location could add an element of timing to battle attempts: “The dragon should land in X turns, so that would be a good time for close-combat weapons.”

Risky battles: With deterministic, CRT-based combat, there’s no reason to ever attempt to fight the dragon too early. Adding in some dice-based randomness might make risky attempts worthwhile and create memorable moments.

Losing turns: With no ability to predict what the town and hamlet tiles might be, pulling one that causes you to end your turn early, lose a turn, lose items, or lose companions is brutal. I’m not sure “lose a turn” belongs in modern designs.10

Even with those five changes, Dragonslayer would transform from a just movie tie-in game to something more memorable. As a solo game, the idea of traveling around a kingdom, powering up, and eventually fighting a boss monster is compelling!11

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Something to learn from every game: It’s easy to be tricked into looking only at the BGG Top 100 games and the ones we consider the best designs. We can learn something from every game we take the time to explore and analyze in detail — even movie tie-ins from the 1980s.

Fantasy without the combat: Not every dark fantasy game needs to be primarily combat. Using combat carefully and at the right time (e.g. climactic ending) can create some really memorable player experiences vs. just hacking endless skeletons.

Old games as design exercises: It can be a useful design exercise to take an older game and think about what you’d change to make it more interesting, fun, and engaging. Try to retain the core concept, but replace some of the older mechanisms with modern ones. Think about how you can increase player agency. Make some changes to make the game more memorable.

What do you think? Do you have any traumatic memories of the Dragonslayer film or board game? Does it sound like a fun game? What would you change to make it better?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

M. Allen Hall, very much a friend of Skeleton Code Machine, will have a booth at PAXU. You can check out his MÖRK BORG and Liminal Horror wares at Booth #4303.

As of the time I’m writing this, the leaders are currently: Forbidden Psalm, Rangers of Shadow Deep, Fire Parsecs from Home, Frostgrave, and maybe Planet 28 and/or Space Weirdos. This is all subject to change and how I try to pack all this into just five posts. Take the survey to let me know what you think.

This scene horrified me as a child as she spits on her hands and bloodies her wrists trying to get out of the manacles… only to die anyway. Not the usual Disney production for sure.

The SFX were nominated for Best Visual Effects and Best Original Score at the Academy Awards that year, but lost both to Raiders of the Lost Ark and Chariots of Fire. Tough year.

SPI was founded by Jim Dunnigan of wargame fame and eventually published Strategy & Tactics for many years.

This is from a full-page ad inside Ares #9 a sci-fi magazine. There’s also an interesting interview with producer Hal Barwood about the film.

There are also King’s Men tiles that are controlled by players. These are moved after taking actions with your magician, blocking other players and slowing down their progress.

For a game that claims to take “two to three hours” to play in the rules, I’m rather shocked to see that it includes player elimination. Granted, you choose when to fight the dragon (for the most part) and you can calculate the results ahead of time, but still. Getting knocked out of a three hour game is rough.

Of the 75 total tiles, 17 random tiles are not used in each game. That’s a nice touch so you never know exactly which items will appear in a given play.

I thought roll-and-move was outdated before I played Magical Athlete, so I’m open to the idea that losing turns in games can be fun.

In fact, Exeunt Press has a game very much like this in the pipeline. It’s been there a couple years now, trying to overcome some of the design challenges seen in Dragonslayer.

Exeunt Press: "I’m not sure “lose a turn” belongs in modern designs."

Me: "But once EVERYONE loses a turn, NO ONE does! (evil laugh)"

Never played the game. Saw the movie on late nite tv though. Thanks for telling us!

An open mine will alwsys learn something...never judge before reasoning about a thing. One might learn a surivial trick.