Use inductive reasoning to talk to aliens

Exploring deduction and induction games and learning the differences between the two using Signal (DVC Games) as an example. Can we make more highly thematic induction games?

Last week we learned about ISBNs, MARC records, and how to get your games included in your library’s online catalog.

Also, there new a simplified ordering system for Tumulus subscriptions. You can still get Tumulus 04 if you subscribe today.,,

This week we are exploring inductive reasoning games — specifically one that has players communicating with aliens. Signal by DVC games is a really interesting game with more theme than you’d expect in a very small box.

Deductive vs. inductive reasoning

Without going full David Hume on the topic, it’s worth understanding some key terms. Specifically, the difference between deductive and inductive reasoning:

Deductive reasoning: Using general rules and evidence to arrive at a specific conclusion that is guaranteed to be true. If the premises are true, the conclusion must be true to a high degree of certainty.

Example: All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore Socrates is mortal.

Inductive reasoning: Using observations and evidence to arrive at a general conclusion that is likely to be true. This type of reasoning is probabilistic and relies on making a “best guess” that may be incorrect.

Example: Every swan that I have seen has been white. Therefore all swans are probably white.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes is often associated with deductive reasoning when, by strict terms, he often engages in inductive reasoning or abductive reasoning. Holmes’s observations (usually) do not lead to a conclusion guaranteed to be true, but rather are likely based on the evidence presented.

Put another way, deduction is about certainty and induction is about probability.

Which is why there has been an epistemological debate about the problem of induction since perhaps the beginning of philosophy. While inductive reasoning may work well for Sherlock Holmes, it is significantly less reliable for the Thanksgiving turkey.1

Deduction games

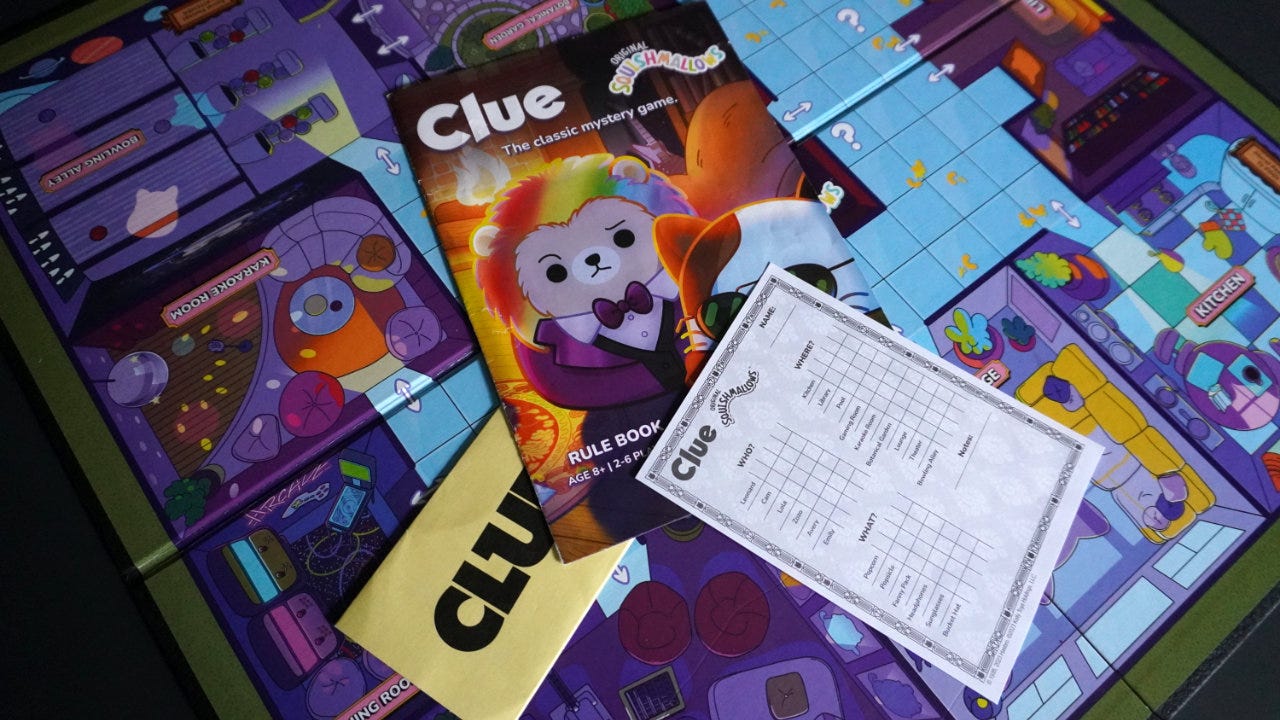

The most basic type of deduction game is Clue (Pratt, 1949) also known as Cluedo outside of North America. This murder mystery game has players attempting to deduce the who, where, and with what of the crime (e.g. Miss Scarlett with the candlestick in the billiard room).

Mechanically, this is done with decks of cards for the suspects, rooms, and weapons. One of each is chosen at random and placed in a little envelope or sleeve so that they can’t be seen. Because the total set of each is known and there are no duplicate cards, the ones in the envelope can be deduced by a process of elimination.

Players take turns making guesses such as, “I suspect it was Mrs. Peacock with the dagger in the dining room.” If another player shows one of those cards (e.g. Mrs. Peacock), it can be eliminated from the possible cards in the envelope — an example of deductive reasoning.

Although BGG currently lists Mastermind (Meirowitz, 1971) as an example of an inductive reasoning game, it is mostly a deductive game. One of the players is attempting to reveal a hidden sequence of colored pegs in a board by making repeated guesses. The feedback to each guess (in the form of white/black pegs) is always truthful and always based on fixed rules. The “code” to reveal is always a sequence of the same number of pegs of different color.

The modern genre of social deduction games such as Blood on the Clocktower (Medway, 2022), Dead of Winter (Gilmour-Long & Vega, 2014), and The Resistance (Eskridge, 2009) usually blend true deductive reasoning with inductive reasoning. While Clue relies solely on deductive elimination and always-truthful answers, many social deduction games rely on bluffing, lying, and other ways to prevent complete certainty.

Induction games

While it’s easy to understand how a deduction game works, including more complicated social deduction games, it’s a bit harder for most to wrap their heads around induction games.

The common elements of induction games include:

Game master: There is often a single player (e.g. GM) who has access to the hidden information. The other players are attempting to use inductive reasoning to discover that information.

The rules are hidden: The hidden information in an induction game is quite often the rules of the game. The players are attempting to infer how the rules are structured or how they are specifically implemented.

The possibilities are infinite: While not always truly infinite, the actual range of possible “solutions” are so broad as to be practically infinite. Contrast this with the fixed number and colors of the pegs in Mastermind noted above.

Signals vs. answers: Rather than direct, perfect-information, always-true answers, the responses to guesses in induction games often rely on observing behaviors and patterns that only hint at the truth.

The classic example of a modern induction game is Zendo (Bradley & Tjan, 2001) in which players build structures to determine a hidden rule in the game:

“Zendo is an inductive logic game in which the players compete to figure out a secret rule. One person will moderate, providing answers to questions about the secret rule. Players take turns building new structures of game pieces, each of which will give them insights about the unknown attributes of the secret rule.”

One player is the Moderator (i.e. GM) and the other players attempt to determine the rules of the game. Unlike Mastermind where it is known that the “code” must be made up of four pegs and six possible colors, the options on how to interpret the Moderator’s examples are almost infinite.

Let’s look a specific induction game that I recently played called Signal.

Communicating with aliens

In Signal (Beatrix, 2025), players become linguistic experts attempting to communicate with an alien. One player is the alien and has access to the hidden rules of the game scenario. The other players are the experts, making attempts to communicate and using inductive reasoning to infer the hidden rules.

Without explaining the rules in detail, here’s how it works:

Setup: The alien player selects a card that describes the hidden rules for the scenario as well as the goal state for pieces: “Not touching, in a rectangle.”

Transmitting: The expert players transmit a message to the alien by placing up to ten pieces (discs, bars, triangles) on a playmat.

Responding: The alien responds to the message by moving the pieces on the mat, following the hidden rules on the back of the card. The rules might be “Move all white pieces toward black pieces.” or “Remove all black pieces touching at least two other pieces.”

Checking for success: If the resulting pattern of pieces on the mat (after the alien has moved them according to the rules) matches the original goal state on the card, everyone wins that round.

Add another rule: After winning a round, the game continues by adding another alien movement rule on top of the first rule. This continues for up to three total rounds, each slightly more complex than the one before.

Signal is a cooperative game, so either everyone wins together by learning to communicate or everyone loses together.

It’s a fascinating example of inductive reasoning where the possibilities are almost limitless. Having played on the expert side, it’s a strange feeling to place the pieces and then wait to see how the alien moves them around on the mat. The first few attempts are nothing more than stabs in the dark — uninformed guesses. Eventually, patterns start to emerge (e.g. “Hrm… maybe if black touches white it is removed?”) and better guesses can be made. Eventually the rule is discovered, the alien’s moves generate the target pattern, and you move onto the next rule.

Thematic induction games

While Zendo is mostly an abstract game, Signal is highly thematic. While there are almost no Layer 3 thematic elements, it still feels like communicating with an alien. The core gameplay itself is what conveys the theme, along with some sparing uses of art and terminology on the cards.

In fact, other than the need for specialized components (i.e. the discs, stars, triangles, and other communication pieces), I could imagine Signal being published as a TTRPG zine instead of a board game. The rules are simple. It works well as a duet or with three players. And it’s considerably more fun if you allow yourself to be immersed in the Arrival-esque theme.2

Just like how The King’s Dilemma (Hach & Silva, 2019) feels like a TTRPG with board game mechanisms and Emerwind feels like a board game with TTRPG narrative, Signal blurs the line between board game and roleplaying game.

I can’t help but wonder how inductive reasoning could be used in other TTRPG designs — especially murder mystery games or cyberpunk hacking.3

The challenges I see include:

There must a GM who has access to the hidden rules (or information) to be discovered. It is the GM who provides signals and feedback after each player guess. This means that GM-less and solo induction games are extremely difficult to design.4

Keeping information hidden and providing different ways to make guesses might rely on physical components. Both Zendo and Signal create interesting, large solution spaces by using manufactured components. Trying to do this with only stock items (e.g. playing cards) and making it thematic would be a challenge.

Of course, these challenges are not insurmountable. If anything, they point to an area of thematic and roleplaying game design that begs to be explored.

I have City of Six Moons (Holland, 2024) on my shelf to be played.5 While not currently listed as an induction game on BGG, it certainly would seem to meet the criteria for one from what I know so far. The box contains the components of a game and a rulebook written in alien symbols. There are no instructions. Part of the game is attempting to decipher and infer how to play. There is no way to know if you got it right or not!

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Deductive vs. inductive reasoning: It’s easy to mix up these definitions because they are so closely related and sometimes overlap. At a high level, however, you can think of deduction as premises leading to a clear and certain conclusion. Induction is closer to a Bayesian inference, using past evidence to make a best guess about a probable solution.

Inductive reasoning games: While deduction games are focused on discovering or uncovering hidden information, induction games are often focused on discovering the rules of the game itself. This could be for the game as a whole, or more commonly, for a specific scenario or instance of the game as in Signal.

Hard design spaces are fertile ground: There are certain game design spaces that seem particularly hard such as naval games.6 While challenging, these difficulties indicate unexplored areas of the game world that can yield true innovation. They aren’t to be avoided, but rather actively engaged.

What do you think? Have you played any deduction or induction games that you really enjoyed? Can you think of TTRPGs that use inductive reasoning as a core mechanism? Does the problem of induction really mean that there is no non-circular way to justify inductive inferences?7

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Design and artist JP Coovert made a great video called Can I make the perfect TTRPG? which features Make Your Own One-Page RPG from Skeleton Code Machine and Exeunt Press! Check it out to see how it puts the guide to work to create a new roleplaying game system.

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

The turkey illusion is a variation on Bertrand Russell’s original formulation, but retains the same idea — a turkey is fed and sheltered every day until it is turned into dinner. The original from Russell’s The Problems of Philosophy goes: “Domestic animals expect food when they see the person who usually feeds them. We know that all these rather crude expectations of uniformity are liable to be misleading. The man who has fed the chicken every day throughout its life at last wrings its neck instead, showing that more refined views as to the uniformity of nature would have been useful to the chicken.”

It’s been a while since I’ve seen Arrival (2016), but if I recall, passing messages back and forth with the aliens was a key part of the film. I should watch it again.

I’ve talked about emergent murder mystery games before with The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game by Adam Bell as a good example. Other examples include Waffles for Esther and the Hints and Hijinx system, both by Pandion Games. While these games are really interesting, I don’t consider them to be deduction or induction games. Instead they have the players developing the solution to the mystery as the game progresses, only to be “locked in” at the conclusion. By definition, there is no solution at the start of the game.

It probably relies on some definitions of deduction vs. induction, but Black Sonata might be close to a solo induction game. And yet because the actual solution space is so constrained and the feedback is always complete and true, I’d tend to agree with the BGG categorization that it is a deduction game and not an induction game.

Please, no spoilers.

You can read about the special problem of naval games as a “best of” article in Tumulus Issue 04 which is now shipping for new subscriptions.

I’ve tried so hard to include a “I Kant even.” joke is here somewhere, but failed.

This is fascinating. I assume it's inspired by the 2016 movie Arrival. Great film and interesting premise for a game. I've never played anything like this, but I'm down to give it a go.

It's an experimental game so I don't know how well it works in practice, but there's a mechanic in my game Sunshine Over My Shoulder where you can get evidence to make inferences but never know for certain whether the software project the characters are working on is "ready to ship". I pulled it out into a standalone subsystem for my Mosaic Strict module Big Technical Project. They both use a GM-like role to track some hidden information.

https://gamemaru.itch.io/sunshine-over-my-shoulder

https://gamemaru.itch.io/big-technical-project