Everything is pointcrawl!

Exploring hexcrawls, pointcrawls, and other crawls to see if everything is actually just a pointcrawl. How can we reduce the illusion of choice and instead have players make meaningful decisions?

This post was nominated for an award at The Bloggies! Round 1 voting is open February 15 - 17, 2026. Show your support and vote! Also, you can listen to a reading of this post at the We Read the Bloggies podcast: Everything is pointcrawl! read by Exeunt Press.

Work continues on Exclusion Zone Botanist: Epsilon (Epsilon) which I’m hoping to launch in early 2026.1

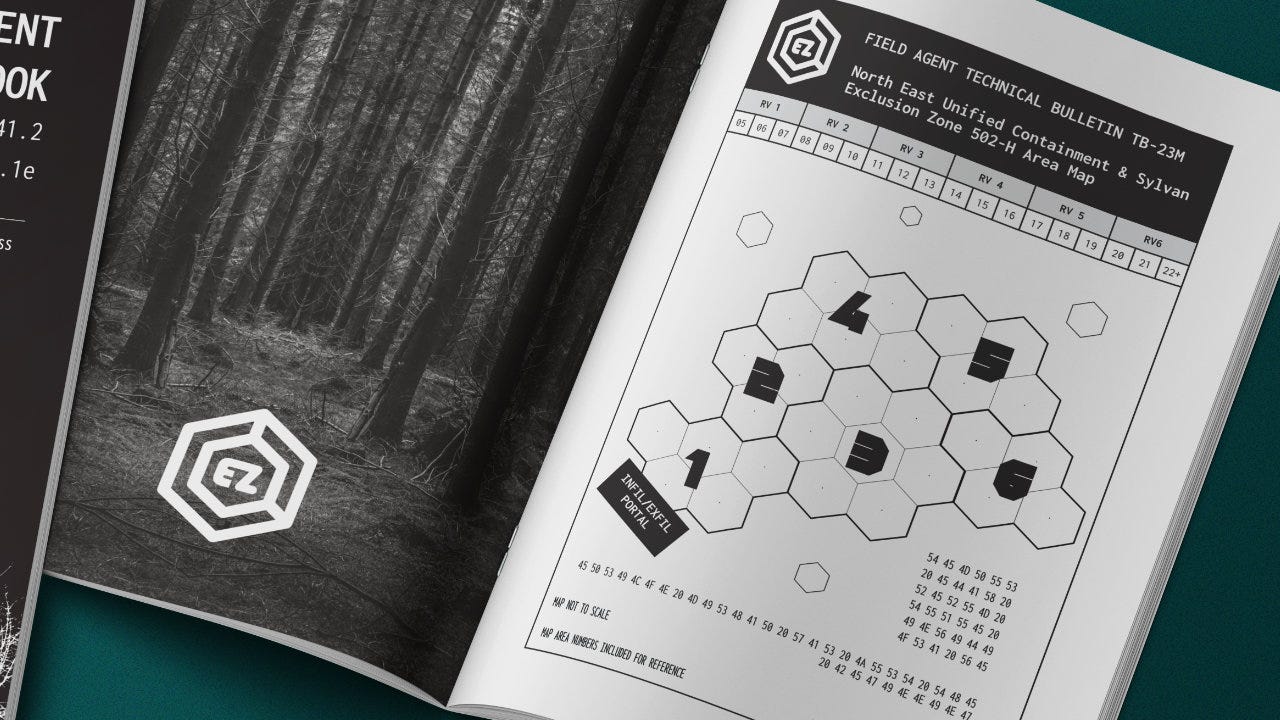

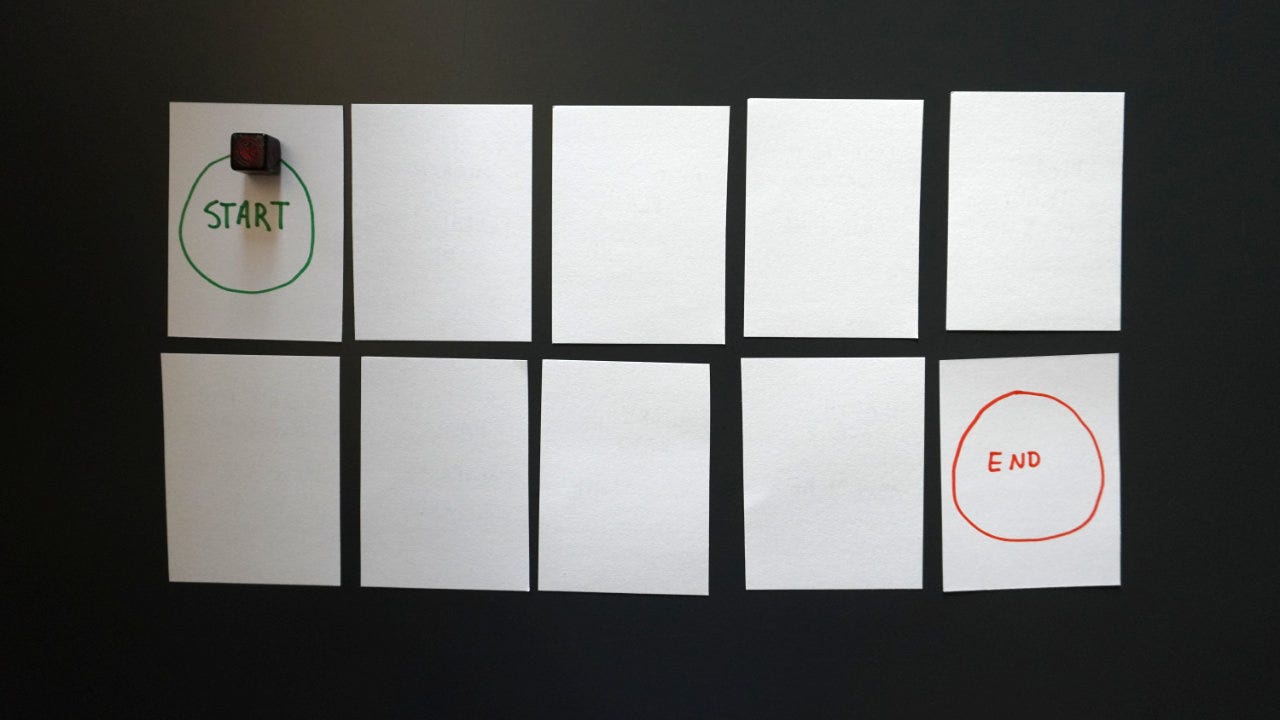

The original Exclusion Zone Botanist (EZB) used a small hex map as part of its core game loop. Each turn you move to a new hex, roll some dice to see if you discovered a weird plant, and then continue. Plants are more likely to be found in areas deeper in the exclusion zone, incentivizing the player to push into the forest. Of course, that means a longer trip back out and more risk of corruption.2

The original EZB map has 28 hexes arranged into six areas numbered 1 - 6. Players start and end at Area 1. If they want to try to get to Area 6 using the most direct path, they must cross through Area 3. With limited time, it makes sense to do this — the shortest path means a higher chance of survival.

This works fine in a game like EZB because (1) it’s a smaller game (~1-2 hours) and (2) the map isn’t the main focus of the game — the discovery, drawing, and time pressure is what makes it an enjoyable experience.

It did, however, make me think about player agency, false choices, and Hobson’s choices in hexcrawls and pointcrawls.3

Given a hexcrawl of sufficient size…

In the world of TTRPGs, there are various kinds of “crawls” that are used as frameworks for adventures. Some of the most common types are:

Dungeon crawls: Players explore a dungeon as a series of interconnected rooms. Each room is stocked with features to see, explore, and discover. The rooms might be adjacent and connected with doors or far apart and connected with hallways. Rooms are often numbered while corridors are often not.

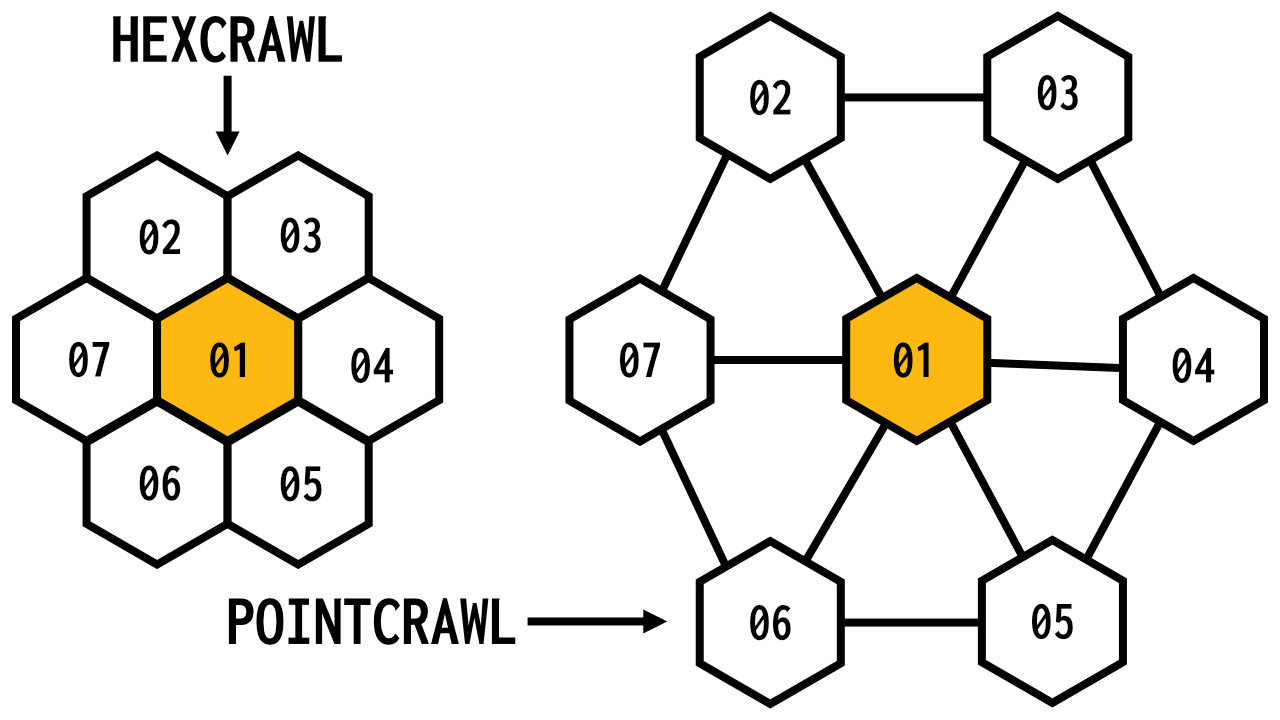

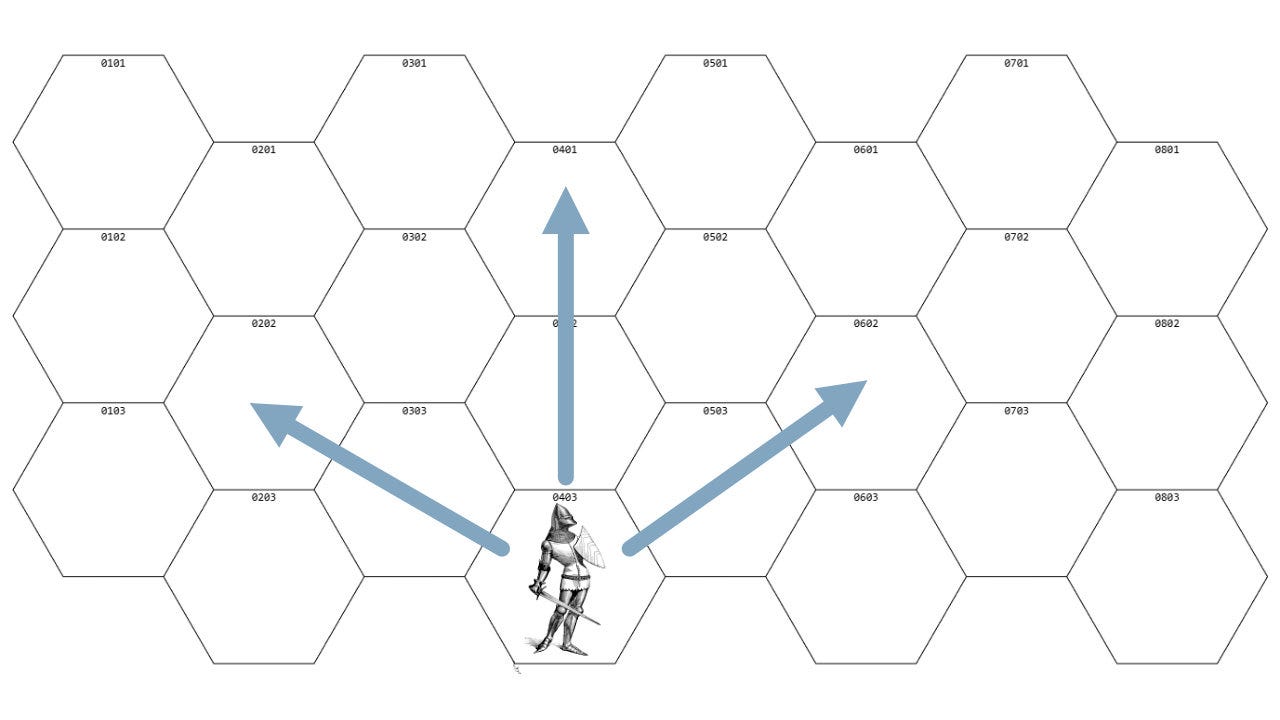

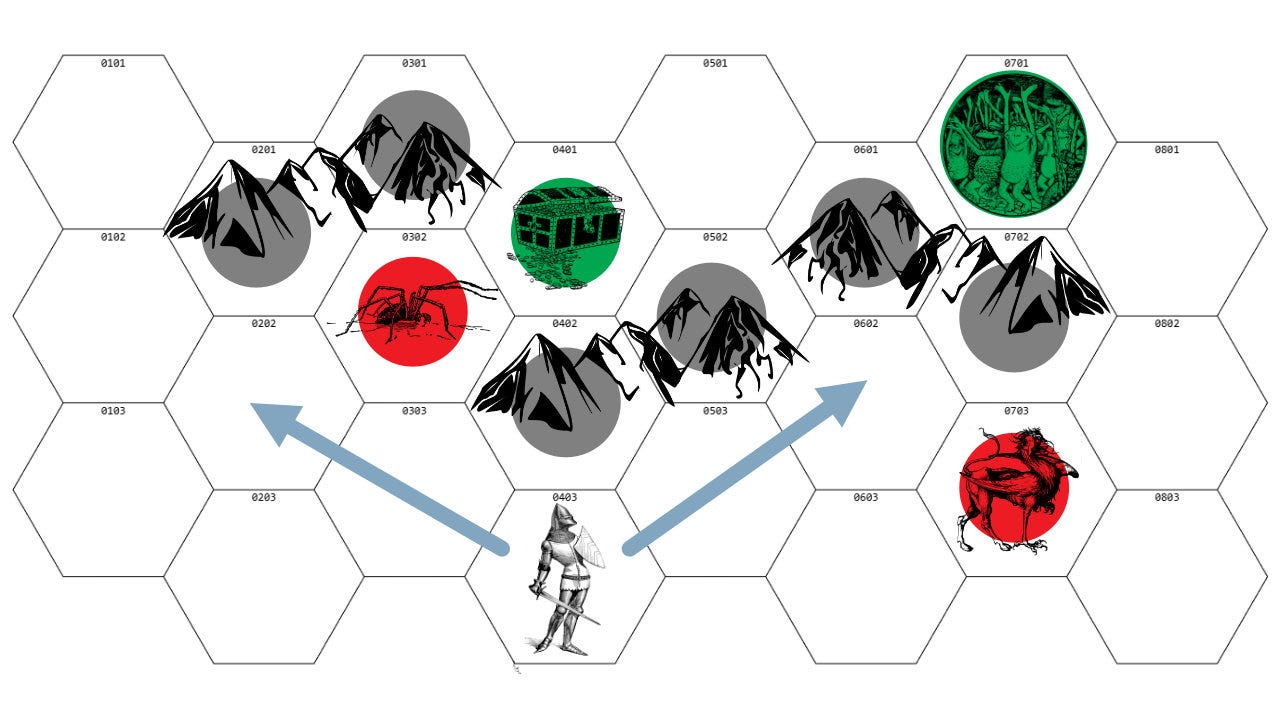

Hexcrawls: Often used for overland or wilderness adventures, players explore a map divided into equal-sized hexagonal areas (i.e. a hex grid). Maps often look like the hex maps you’d find in a historical wargame. Players can move from their current hex to any adjacent hex, depending on terrain and other conditions.

Pointcrawls: A pointcrawl is an abstraction of common maps, representing notable locations as points (often shown as circles). Each point is connected to others by fixed paths shown as lines between the circles. It limits player movement to the connected points, forcing movement along travel corridors to landmarks or important locations.

The above are general descriptions with common elements and not strict definitions. They can be mixed and combined into urbancrawls (i.e. a point crawl in a city) or wavecrawls (i.e. hexcrawl on the sea).4

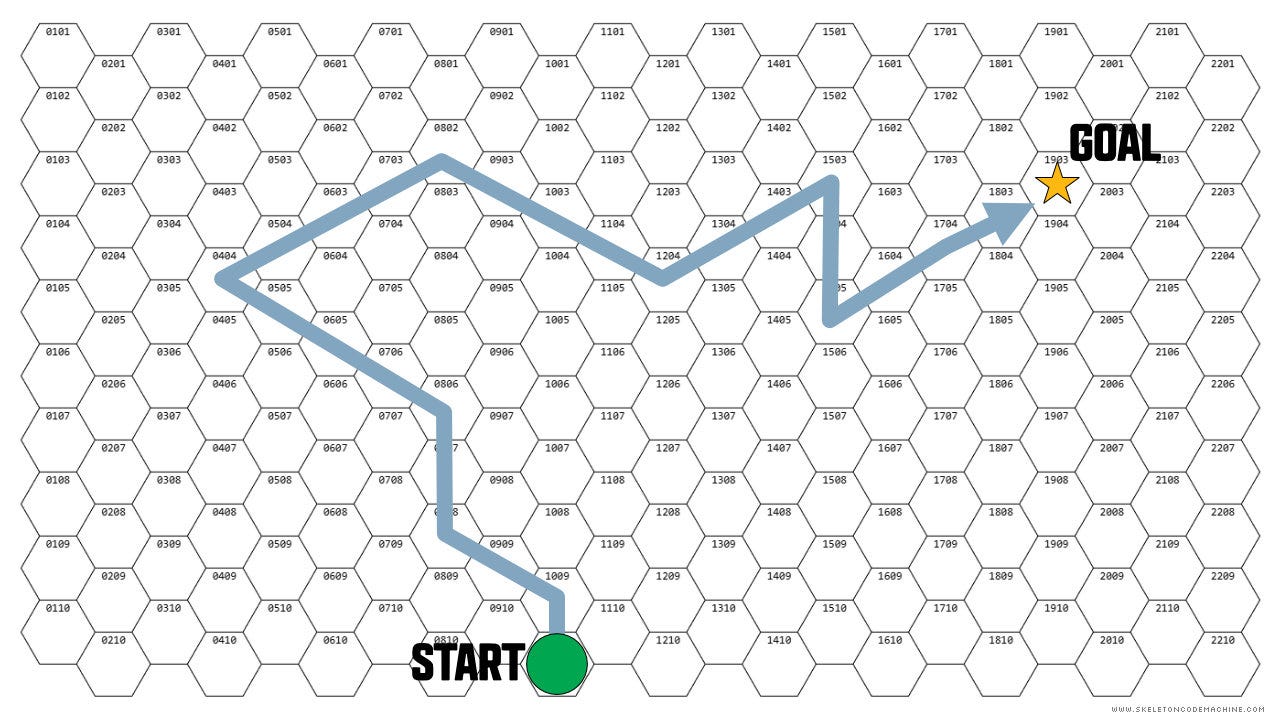

Now imagine a hex map of sufficiently large size but with almost no terrain or points of interest defined on it. It’s a big blank hex map with perhaps only one goal or target location marked on it. This isn’t how most TTRPG overland maps are designed, but bear with me…

A rational player, assuming limited time and resources, will take the shortest path from their starting location to the goal. If they need to escape the map after the goal, they will almost certainly again take the shortest path back out. In many cases, this means simply retracing their steps and revisiting the same hexes.

Add another target location on the map, and they would do the same thing — taking the shortest route between the start and two target hexes. All other hexes would likely be ignored.

So given a field of hexes with one optimal path through them, what is it but a point crawl with extra steps?!5

Everything is pointcrawl!

As in the Risk (Lamorisse & Levin, 1959) example that I use when discussing theme vs. mechanism in design classes, most games can be reduced to network diagrams.

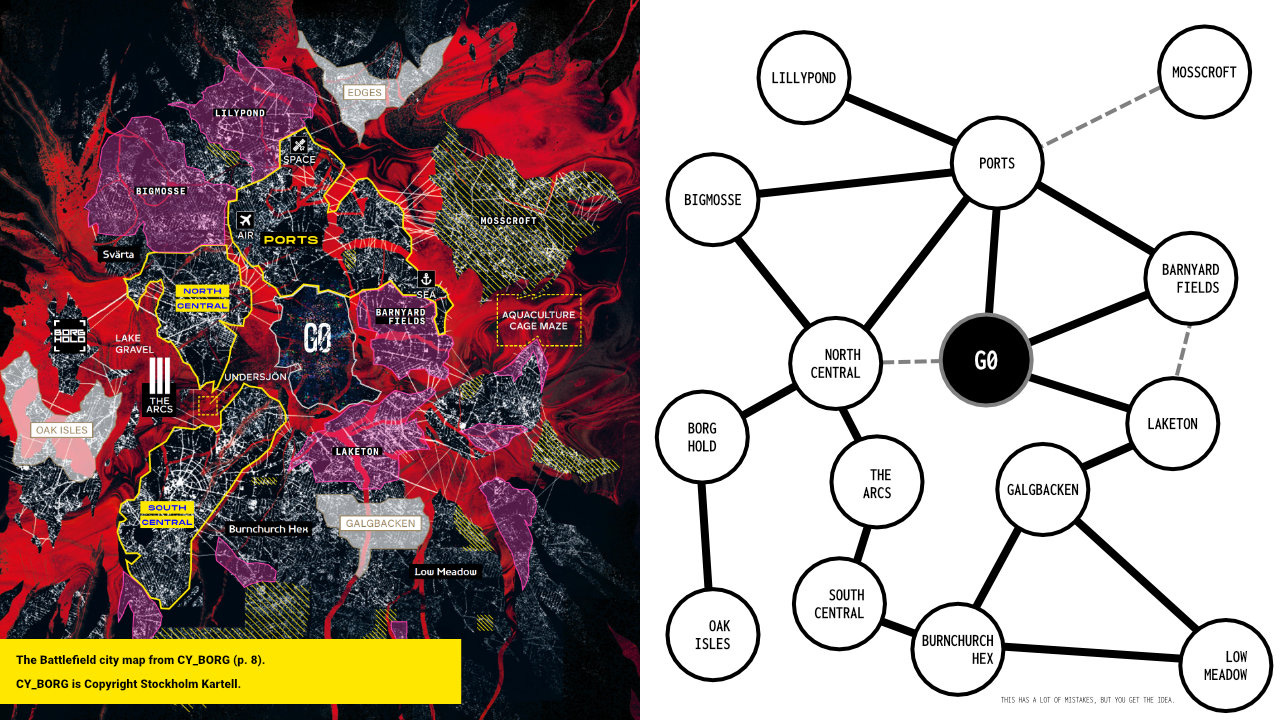

With Risk, each area can just as easily be represented by a dot connected to others by simple lines. We could do the same thing with the six areas in Pacts (Brin, 2025) or the city map in CY_BORG. In all three cases, however, it would strip layers of theme out of the game in an undesirable way.

Similarly, hex maps could be represented as a network diagram of dots and lines. Imagine each hex as a node with six connections, one from each side — spreading out the hexes and connecting them with lines.6

If our imaginary hex-to-pointcrawl map had one optimal path through it, we could easily strip away the unnecessary hexes. This would leave us with a simple pointcrawl.

Why choose one vs. the other?

So if everything can be represented as a pointcrawl (i.e. a network of connected locations), why would we ever use anything else? This is one of the topics that gets endlessly debated online, so we aren’t going to settle it here.

But we can, perhaps, create a list of pros and cons to help guide our decisions:

Hexcrawl (adjacent hexes)

Pros (+):

Equal-sized hexes can provide a sense of distance between locations.

No restriction in movement direction. Other than designed obstacles (e.g. an impassable mountain hex), players can move freely in six directions.

Gives the ability to emphasize travel, making each hex potentially risky or rewarding and consuming resources.

Easier to model wandering and getting lost in wilderness settings.

Supports simulationist designs that want to model terrain, elevation, weather, travel speed, line of sight, and resource depletion.

Easier to hide locations and content vs. a pointcrawl where (by definition) all of the interesting points are shown on the map.

Cons (-):

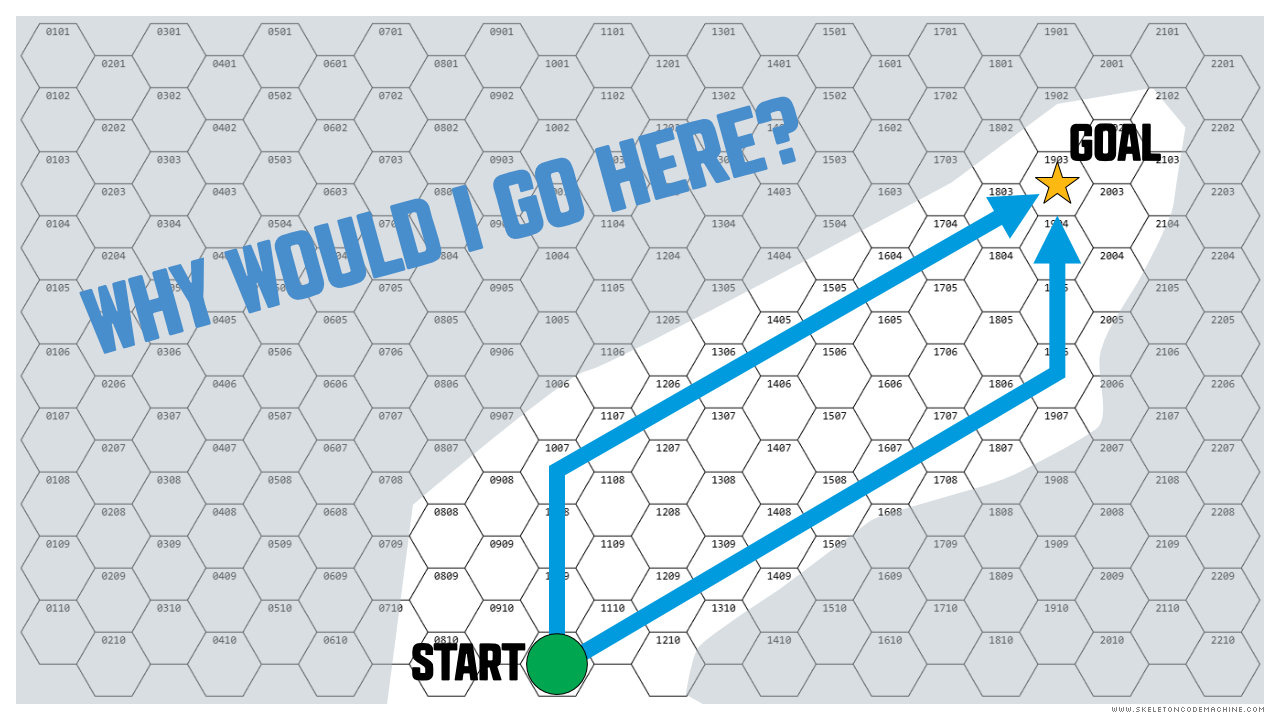

Without explicit reasons to visit the entire map, most of the map will go unexplored. Players may race to and from points of interest, meaning the actual effective map is much smaller.

If the terrain and/or landmarks are determined by dice after moving into a hex, it might create the “snow next to a desert” problem that arises in purely random generation. Markov-like solutions such as hex flowers might help.

Risk of feeling boring or like a grind when moving through hexes that don’t have enough interesting things in them. Even a D66 random table could start to yield repeats after a while.

Pointcrawl (connected nodes)

Pros (+):

Large distances between points can be abstracted as lines while relative distances can be shown by comparative line length.

Paths can be curated to create interesting choices. For example, a longer risky path vs. a shorter dangerous path or a combat path vs. a stealthy path.

Reduced preparation when used in traditional TTRPGs as only the important places need to be defined and populated.

Travel can still be meaningful if not well defined. Resources can be depleted as necessary, time passes, and even have a chance for random encounters.

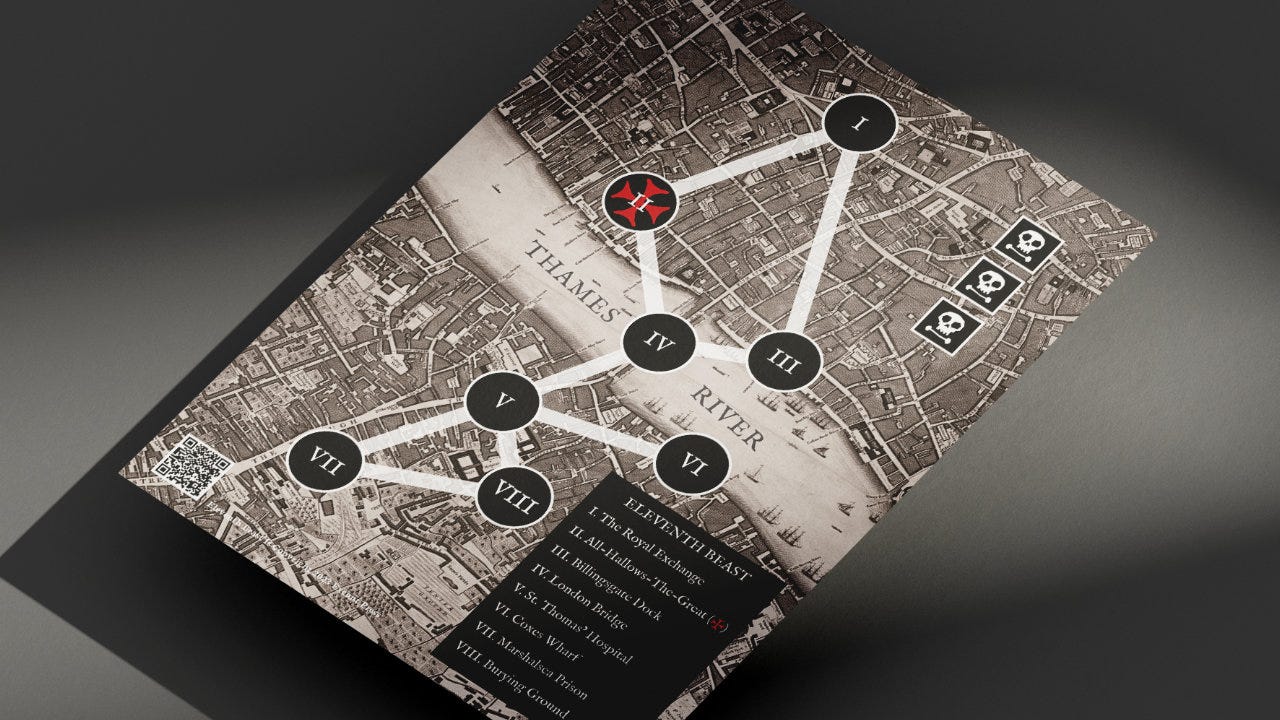

Can easily be overlaid on existing maps, particularly ones with a lot of graphic detail. Also, the connecting lines can be bent and curved to fit terrain and features on the map.

Abstraction allows pointcrawls to work in almost any setting from wilderness to cities to dungeons to the open sea. With an appropriately drawn map under the nodes and lines, it can feel quite thematic.

Cons (-):

Travel between points is largely skipped, meaning all the focus is just on the points of interest. This might make the game feel procedural and like players are “fast traveling” around the map.

Reduces the chance of discovery (or at least the feeling of discovery) by wandering off the main paths. Content only exists in the defined nodes and the rest of the game world can feel empty.

No shortcuts or improvised solutions. In a hexcrawl, a player might try a doomed shortcut through an impassable mountain hex. In a pointcrawl, the map would need to be modified to move between non-connected nodes.

Which type of map or solution you choose depends on what kind of fun you want your players to have, which thematic elements you want to emphasize, and what kind of story you want to tell.

Hexcrawls, pointcrawls and false choices

I’ve covered the concept of false choices quite a few times, but it bears repeating. Players can be presented with choices that appear to meet the criteria of the CCI model and yet are actually just the illusion of choice:

Lack of information: The player has no information or knowledge by which to make the decision. All options seem equally good or bad, and a random selection is as good as any.

Undifferentiated outcomes: The choices all lead to the same outcome, regardless of the option selected.

Overwhelming randomness: The output randomness built into the system greatly outweighs the impact of any actual player decisions based on available options.

In the examples above, the player has no information by which to choose one hex versus another on their way to the target hex. All adjacent hexes are equally good or bad before their contents are revealed. The consequences are determined by output randomness when rolling dice to see what is found after moving. This could also be true for a pointcrawl with nodes that aren’t defined until the player explores them.

Such a map would result in what I’d consider the illusion of choice. While the player can choose any connected node or adjacent hex, it doesn’t really matter. There is no information available to guide the decision and any choice is outweighed by the resulting randomness.

Ways to reduce false choices

The easiest solutions to this potential problem include:

Multiple objectives: Create multiple objectives or targets on the map so there isn’t one obvious path to and from the goal. These can be open information on the map or personal objectives tied to specific player characters.

Curated paths: Design interesting paths created by impassable terrain, dangerous locations, rewards (treasure), pointcrawl choke points, or other similar map features.7 Of course, this changes the map from one of pure exploration and randomly generated features to one that is (at least partially) fixed.

Changing paths and threats: In Eleventh Beast, once the Beast appears on the map it moves toward the Hunter each round. This blocks paths and provides a reason for the player to choose a different route. Having mobile threats (e.g. the Beast) or changing routes (e.g. impassable mudslide or unlocked shortcut) can create interesting choices for the player.

The above solutions are all focused on solo games where there isn’t a GM who can adapt as the player(s) move across the map. They also assume that the game is largely based on exploration with few pre-defined features.

With a GM, you’d be able to incorporate foreshadowing and clues to inspire different routes. Additionally, a GM could allow for scouting mechanisms (e.g. climbing an overlook to spot a distant tower).

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Hex and point crawls have much in common: While it’s amusing to say that hexcrawls are actually pointcrawls without the lines, there is some truth that there are similarities. Players are moving between locations via allowed (legal) connections. Hexes typically have six outbound connections (faces) while points can have an arbitrary number of outbound connections.

The “right” one depends on your goals: It is, of course, impossible to say whether hexcrawls or pointcrawls are better no more than you could say a hammer or a saw is better. It depends on the type of player experience you want to create and how the map works with all the other mechanisms in the game.

Beware the illusion of choice: Players may have multiple linked locations to choose from, be able to select one of them, and have the outcome impact the game state. That doesn’t mean it’s a fun choice, however, if there was no way to make an informed choice.

What do you think? Are hexcrawls just pointcrawls with extra steps? What are your criteria to know when to use a hexcrawl and when to use a pointcrawl? If you had to pick one, which team would you choose?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want more in-depth and playable Skeleton Code Machine content? Subscribe to Tumulus and get four quarterly, print-only issues packed with game design inspiration at 33% off list price. Limited back issues available. 🩻

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

The question of “When will it launch?” is a difficult one. I don’t have an exact date because it depends on the completion of most of the game. For my reasoning and discussion of this, check out the October 2025 Epsilon update.

For a full description and Python simulation of the risk value mechanism used in Exclusion Zone Botanist and You are a Muffin, check out Muffins and the Risk of Being Eaten.

I realize the title of this article is about pointcrawls but the cover image is of a hexcrawl.

The idea of a hexcrawl on the sea was what Ratsail was supposed to be before I ran headlong into the special problem of naval games. The open sea means a lot of hexes where nothing particularly interesting happens. This isn’t an unsolvable problem, but it is a potentially difficult one. A pointcrawl on the sea is one possible solution.

I think I’m mostly kidding here. Obviously pointcrawls and hexcrawls are not the same, as demonstrated in the later section with pros and cons of each. But I do think this is an amusing way to think about them. Let me have my fun.

You already kinda mentioned it, but a quick fix is as easy to add danger icons to longer paths in pointcrawl. You dont know what danger it may be, but you see the longer path has 3 danger icons (3 Rolls in a specific table) and the short path has just one. BUT! The short path end location has a known danger or obstacle.

This is fun!

Classic example of this - the first version of Power Grid (called Funkenshlag) was a ‘crayon rails’ style game where you drew power lines on a hex grid. However the vast majority of the lines were just drawn directly between cities, and had very little variety from play to play. So three years later Friese released Power Grid with a point-to-point map.

The rest is history.

https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/12166/funkenschlag