The special problem of naval games

How wind and weather make sailing games hard to design

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

First, MÖRKTOBER is here! Today begins thirty-one days of making dark and weird stuff for the MÖRK BORG roleplaying game. This year also includes DOOM QUEST, an optional puzzle hunt with chances to win horrible prizes.

When not doing MÖRKTOBER planning and prep, I’ve been thinking about naval and ship-based games.

Other than some fond, but distant memories of playing an old copy of Wooden Ships & Iron Men (Taylor, 1974) as a child, I’d be hard pressed to think of modern Age of Sail games that routinely hit the table.1

Why aren’t there more naval board games? Do they need to be wargames? What would a ship-based TTRPG look like?

The vagaries of the climate and weather

There’s an interesting note on “Special Problems of Air and Naval Games” in The Complete Wargames Handbook (Dunnigan, 1980):

Without belaboring the obvious too much I should point out that most gamers, when forced to choose between games taking place on land, in the air or at sea, will tend to prefer the land games. Naval comes next, a distant second, and an even more distant third is air games.

He goes on to identify a few potential reasons for this lack of interest in naval vs. land wargames:

Uncontrolled combat: Most of the history of naval combat consisted of “large groups of ships sailing or rowing into one another and then proceeding to ram or burn down … the opponents ships.” It lacks the tight control of formations seen on land (e.g. the phalanx and infantry square).

Wind and weather: Even with a skilled crew, the movement of historical naval ships is still “dependent on the vagaries of the climate and weather.” A strong headwind or a good tailwind could impact the battle outcome as much as anything else.

Lack of communication: Until the advent of modern, wireless communication, it was tough (impossible) to quickly coordinate the activities within a fleet of ships. At close range there might be flags, but when you are half-way around the world, messages could take weeks or more to send.

From a more practical standpoint, an open map of blue hexes just isn’t as interesting as a land map with terrain, cities, roads, and other tactical features. Short of a few island or perhaps a coast, it can be hard to make a sea map have the visual appeal of a land map.

Also, naval movement is much trickier to model than land movement. Units on foot, horseback, or even in mechanized vehicles can stop and turn at will. Ships slowly gain speed, make sweeping turns, and slowly coast to their destinations.

Don’t give up the ship

Before Dungeons & Dragons, Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson, and Mike Carr developed a naval wargame. Don’t Give Up the Ship (1974) was their first collaboration together, with Gygax and Arneson writing the basic rules and Carr writing most of the optional rules.

Subtitled Rules for the Great Age of Sail, it’s a simulation wargame of naval combat. In the forward, Gygax notes:

However, while many sets of rules are available for most periods — Ancient, Medieval, Napoleonic, and so on — to my knowledge this is the first effort at formalizing a body of rules to aid the hobbyist to recreate battles at sea from the days of the American Revolution to the War of 1812.

Formatted as a compact (almost A5), 58-page, staple-bound book reminiscent of the modern TTRPG zine, it covers the basics of war at sea:

Ship classes, sails, masts, and guns

Wind direction and force

Movement

Cannon fire and damage

Boarding, morale, and melee

The optional rules cover all sorts of details like sighting, burning ships, studding sails, kedging, longboats, and specialized guns. It’s a dense book written, presumably, for an audience already familiar with tabletop wargaming.

Initial wind direction and force are determined using a rather odd system of rolling two dice (“one is white and one is red”) and determining if they are odd or even:

Red “even” equals a wind from the North or South

Red “odd” equals a wind from the East or West

White “even” equals a wind from the North or West

White “odd” equals a wind from the South or West

The two results are compared and the matching direction is the starting direction of the wind.2 Two six-sided dice (2d6) are rolled and compared to a table to determine the wind force which ranges from 3 - 7. From then on, every 12 hours in game time a roll is made to incrementally change the wind direction and force, increasing or decreasing by one point.

While Dungeons & Dragons went on to become worth billions to Hasbro/WotC, Don’t Give Up the Ship has mostly faded into obscurity. This might be related to the special problem of naval games above. For example, angles matter so much for movement that the game recommends using a protractor — an item rarely associated with a fun time.3

Wooden Ships & Iron Men

Around the same time as Don’t Give Up the Ship, Avalon Hill published Wooden Ships & Iron Men (Taylor, 1974). With a dense, 35-page rulebook, it is a complex game by today’s modern board game standards.4

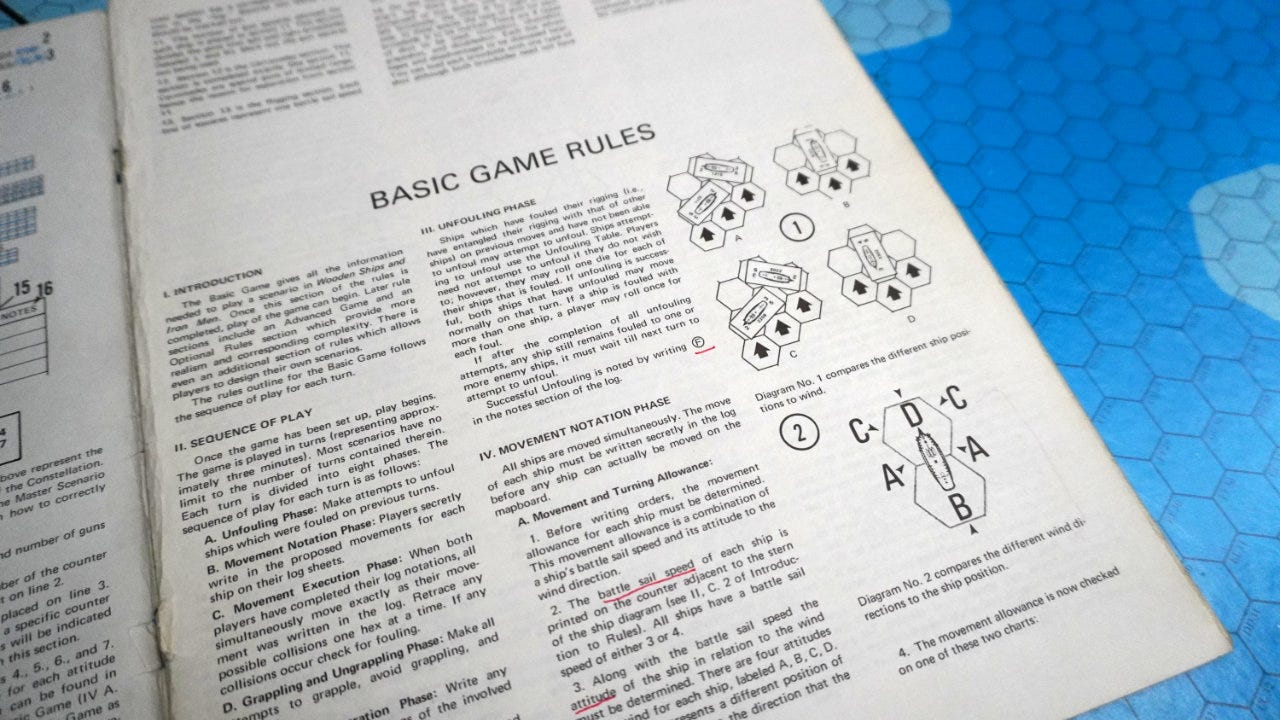

The game operates on a map of blue hexes. Wind is in one of six directions matching the faces of a hex, and impact the attitude of a given ship which is an interesting way to handle it. There are four possible attitudes (A, B, C, D) depending on the ship’s relation to the wind direction.

Depending on the ship’s battle sail rating, the movement rating for that turn will be a value between 0 and 4. Sailing directly into the wind (Attitude D) is always zero. A good tailwind (Attitude B) will either be 3 or 4. Given that movement rating:

A ship can use all or none of its movement in a turn.

A ship must always move forward (direction the bow is pointing).

Ships may only make one hex-face (60 degree) turn per hex.

A ship’s turning ability is the maximum number of turns it can make in a single turn across all hexes traversed.

Attitude may change during a turn as the ship turns into or out of the wind which limits the amount of movement allowed in that direction.

Ships that sail directly into the wind (Attitude D) stop and end their movement.

There are also rules for drifting, causing non-moving ships to slowly drift in the direction of the wind. Optional rules exist for full sails to increase movement allowances, backing sails to avoid collisions, anchors, and disallowing turning in place without moving to a new hex.

In the advanced rules, the wind will change direction every third turn and the wind has a velocity ranging from Becalmed (0) to Storm (6). A “Wind Effects Table” is added that compares the wind velocity, wind attitude (A, B, C, D), and ship type to generate movement allowance modifiers.

Naval combat in Pirate Borg

Pirate Borg (a system based on the MÖRK BORG third-party license) is a key example of how naval combat is handled in modern TTRPGs. While the details are short (p. 73 - 85), they cover all the basics required to simulate single-ship battles at sea:

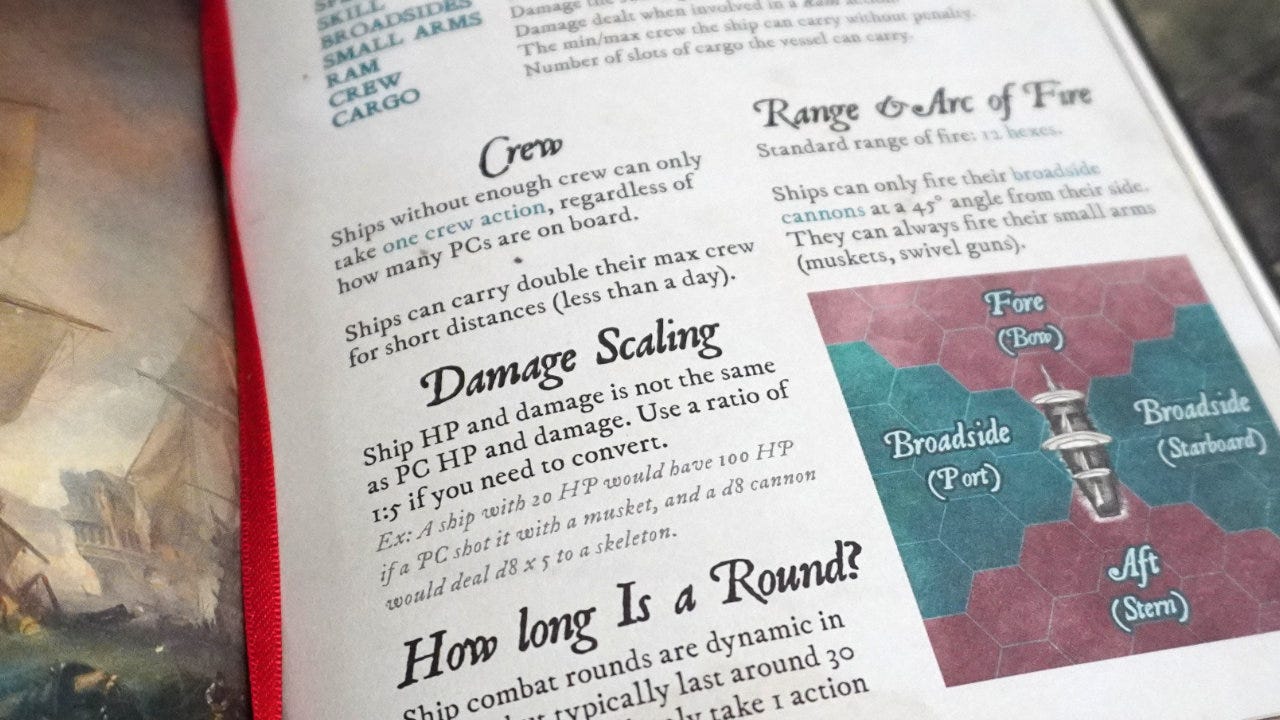

Ship stats: Each ship has hit points, hull defense (sort of like character armor), speed, skill, damage amounts (broadsides, small arms, ramming), a min/max crew, and cargo slots.

Rounds: Like most TTRPG combat, it is conducted in rounds. A hex map is used to track ship positions and facing.

Arc of fire: Rather than detailed firing angles with protractors, Pirate Borg uses simple hex firing arcs similar to BattleTech.

Movement: Ships can turn one or two hex faces per turn, but only once per individual hex. They must also move at least 1 hex per turn (with some exceptions).

Division of responsibilities: One player acts as the Captain and handles moving the ship. The other players can select from a list of Crew Actions (e.g. firing guns, drop anchor, attempt repairs, etc.)

Crits and Fumbles: As a d20-based system, natural 20s result in double damage and reduce the hull (armor) of a ship. Critical failures cause cannons to misfire and require repair.

Sinking: When a ship’s HP is reduce to zero, it is dead in the water. Further damage will probably cause it to sink.

Additional rules exist for specialized crew, morale, cargo, and various upgrades.

Wind is included only as an optional rule. If used, there is an initial d6 roll to determine wind direction (based on hex faces).5 The direction impacts the speed of each ship, potentially slowing it down or stopping it dead in the water. Rather than fixed timing, rolls are made to change the direction “when thematic.”

Core elements of naval games

After looking into a number of sailing ship games, these seem to be a few of the common elements:

Big blue hex map: It’s hard to get around the fact that the ocean can be a big place with few features, and hex maps work great for modeling wind direction.

Wind direction & speed: With the notable exception of Pirate Borg, most games will build wind direction into their model. It is notable that even Wooden Ships & Iron Men leaves wind velocity for the advanced rules.

Ship types and classes: All three games give players a choice of ships, each with different stats and abilities. This reminds me of the joy of configuring your own mech in games like BattleTech.

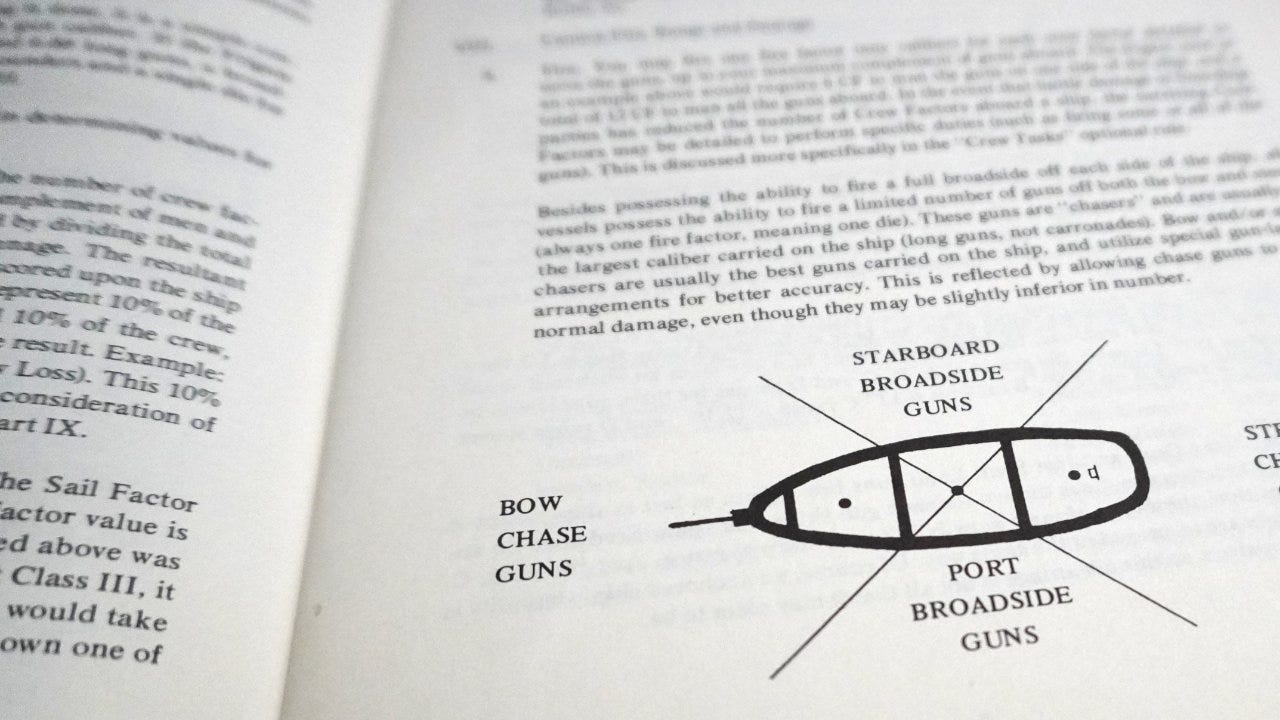

Arc of fire: You can’t fire all your cannons out of your bow. Broadside shots become important and therefore angles need to be calculated. Pirate Borg’s use of BattleTech-style hex based arcs is an interesting simplification.

Damage and hull integrity: In combat the goal is to to sink the other ships, so having some measure of hull damage makes sense. Don’t Give Up the Ship simplifies this by using high (e.g. masts) and low (e.g. hull) damage. Pirate Borg simplifies further into simple hit points.

Crew and morale: A ship is nothing without its crew, so it makes sense to have some way to model that. In Pirate Borg it is player focused, with everyone taking actions. In Don’t Give Up the Ship, it’s abstracted away as Crew Factor (CF) numbers which allow various actions.

Challenges of sailing-ships in TTRPGs

As someone currently working on a game that involves sailing as a core mechanism, designing such a game can be challenging. Sure, you could use a mixture of the rules explored above. They work great for short combat encounters, but they quickly become less interesting if used for longer periods.

Here are some of the challenges I see:

Monotony of travel: Long voyages just aren’t that exciting. With days, weeks, or even months required to complete a single voyage, that’s a lot of time looking at nothing but water and sky. Random encounter timing and quality become critical design elements to keep it interesting.

Lack of terrain diversity: Unless exploring an archipelago, there usually isn’t any change in terrain for long periods. The water depth might change, but unless the ship runs aground, it doesn’t really matter. Environmental hazards might help maintain interest with random fog banks and storms.

Limited roles: On a ship everyone has a defined role, be it captain, navigator, gunner, or cook. Each one is critical, but they aren’t all equally interesting at all times. Smooth sailing or land-based excursions can be boring for the navigator or gunner, while the cook might not feel as valued during ship-to-ship combat.

Slow or abstract combat: If combat is part of the game, it is hard to keep it at an individual player level. Pirate Borg does a nice job of keeping everyone involved, but many times it is more about maneuvers and wind than anything else.

Limited player agency: When player characters are on land, they can go anywhere and do almost anything. There are towns, caves, and forests to explore. NPCs can burst into the tavern to interrupt the action and drop a juicy plot hook. If everyone is on a boat a thousand miles from land, it’s hard to have someone pop in to announce the latest quest. There are fewer choices to be made.

Of course just because design challenges exist doesn’t mean they aren’t solvable. Games like 7th Sea, Alas for the Awful Sea, Privateers and Gentlemen, Shot & Splinters, and God Damn Them All certainly exist, but it is hard to say there are as many as there are land-based games. I’m sure there are more example out there too, including some I simply forgot. Please post in the comments!

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Naval games are tricky: I really think Jim Dunnigan was right that a “special problem of air and naval games” exists. For all the reasons above, naval combat board games are tough. Naval TTRPGs are even tougher.

Mechs vs. ships: While writing this, I couldn’t help but make some mental comparisons between ship-based and mech-based games. They both have these customizable rigs that you pilot. TTRPGs become split between “action” and “downtime” which can fracture the game. I might think more about that during the upcoming Mech Week series.

Hard != Impossible: Just because this is a tougher design space doesn’t mean it should be avoided or that it can’t be solved. Some research into existing games, exploration of mechanisms, and creativity might yield a really fascinating new game.

What do you think? Is it harder to design an interesting game that takes place at sea vs. on land? What games have you played that handled sailing ships the best?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Join in the creative fun with MÖRKTOBER and DOOM QUEST this year. You might win a horrible prize. Read the FAQ at www.morktober.com to get started. 🎃

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

The Age of Sail is usually defined as starting in either the 15th or 16th century and lasting until sometime in the 19th century. It is the period of European history where sailing ships dominated global trade and warfare. Eventually steam power, metal ships, wireless communication, and modern navigation brought the age to an end.

I can only imagine this method was used to get a flat probability distribution for four options (N, S, E, W) while only using a six-sided die (d6). Perhaps d4 dice were not as common as I would have guessed in 1974-1975.

The “Equipment and Space Needed” section of Don’t Give Up the Ship recommends: “Protractor (this will be very helpful in determining movement and firing angles. Clear plastic protractors are best, but any will suffice.)”

Wooden Ships & Iron Men (1974) surprisingly has a 3.09 / 5 complexity rating on BGG. It must be experienced wargamers giving the ratings, because it sure doesn’t seem to be the same complexity as similarly rated games like Obsession and Orléans. That would make it significantly less complex than Root, Troyes, and Power Grid. That said, I don’t remember this as an overly complicated game when playing as a child.

In a wonderful detail, two wind direction tables are included: one for flat-top hexes and one for pointed-top hexes. The style of hex can matter quite a bit in games like this, with travel being a bit easier in certain directions based on flat-top or pointed-top configurations.

Thanks to Eryk for reminding me about Shot & Splinters which belongs on this list: "Shot & Splinters is a tabletop roleplaying game of naval adventure, inspired by Horatio Hornblower, Aubrey & Maturin, and Richard Sharpe. Drawing on history but not beholden to it, the game is set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars, thrusting your characters into the heart of the conflict."

Great article! It left me thinking about space travel, which is often compared to naval travel, and the impossible distances and mind-numbing tedium of outer space. Most games there hand-wave long distances with faster than light jumps or some sort of stasis that lets the story jump past the actual long distance trip. I wonder if there might be a role for that approach in a TTRPG. Once you set your heading and destination, just jump there. Maybe act like a point crawl and roll for an encounter per leg of the journey, but don’t force a hex-by-hex exploration of the open ocean.