The power of zero-agency game design (and a huge baby)

What happens when Baba Yaga, Sisyphus, and a rocket scientist have a race? We learn how player agency (or lack thereof) in game phases impacts player experience. Sit back and watch it all play out.

Recently we explored Who is Reiner Knizia? (and why you need to know). Based on the survey, 47% of readers fell in a range from “not sure” if they were familiar with his work to “never heard of him.” I hope the article introduced some of those readers to some new games that are easy to learn and strategically deep!1

This week we are looking at the opposite of games with tough decisions: games where some of the fun relies on no decisions at all! How can designers use zero-agency phases in games to create satisfying player experiences?

Well, the answer may involve Baba Yaga, rocket scientists, Sisyphus, and a huge baby.

But first…

With a large influx of new readers and subscribers, it’s a good time to remind everyone about Tumulus — the Skeleton Code Machine Quarterly!

Tumulus is a quarterly, print-only zine filled with tabletop game design inspiration. Each subscription includes four (4) issues. Each issue has a different theme ranging from cyberpunk robots to dungeon crawls to hidden traitors. The current issue is Tumulus 04 “Return to the sea.” — shipping now through November 30. The next issue is Tumulus 05 “Step into the fairy ring.” which will begin shipping December 1.

If you enjoy reading Skeleton Code Machine, you’ll love getting Tumulus delivered to your door. You can read the details or subscribe right now!

A limited number of Tumulus back issues are also available while they last.

A quick player agency refresher

I’ve written at length about player agency in tabletop games and what it means to give players a choice. There are many ways of thinking about it and multiple models to choose from, but I prefer the CCI model proposed in The Power of Choice: Player Agency in Tabletop Role-playing Games (Amauger, 2023):2

Choice: Multiple options are presented to the player. This could be in the form of a list of possible actions or open-world, creative problem solving in TTRPGs.

Control: The player has the ability to act upon the options. The player must have the power to make a selection based on their desire.

Influence: The player’s choice changes the world of the game. When the player makes a decision, it impacts the game state in a meaningful way.

This model allows us to quickly test a game’s mechanisms, a specific phase, or the game as a whole to assess how much player agency is truly present. For each game element we can ask: Are choices offered? Does the player control which choice is selected? Does their choice impact the game state?

If it fails any of those three parts of the test, it calls into question how much player agency is truly present.

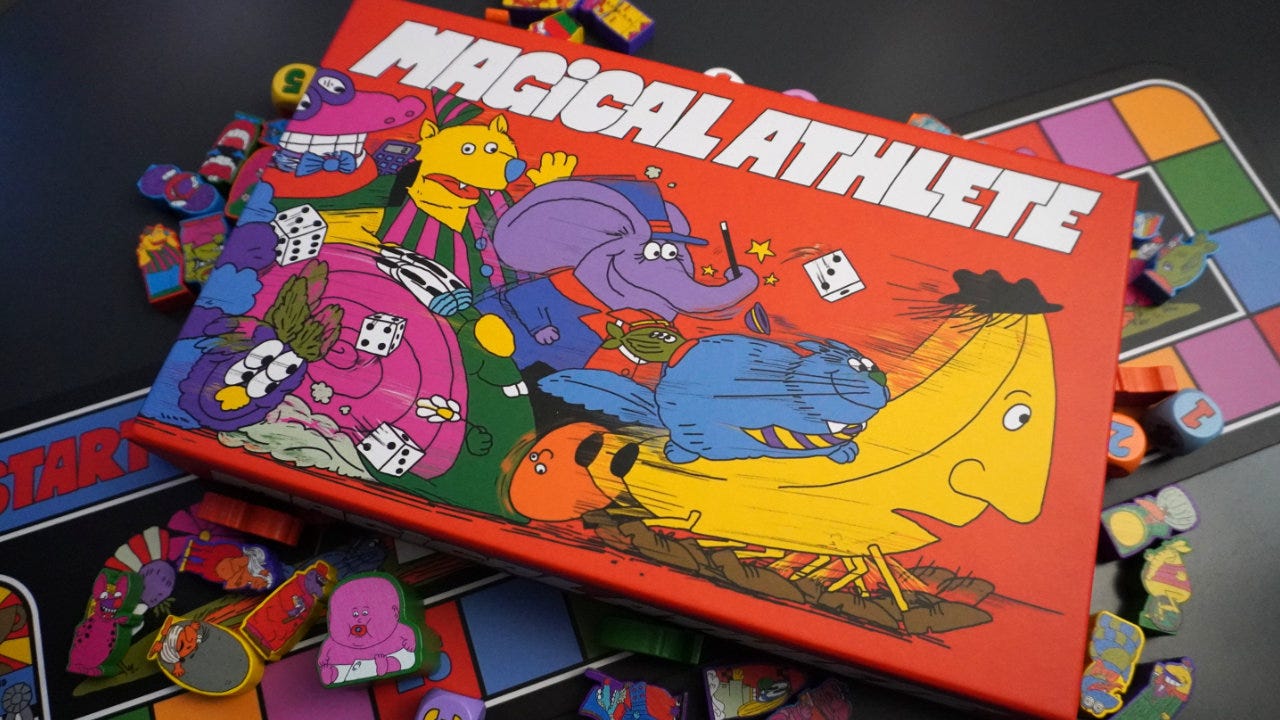

Magical Athlete’s self-running race

Let’s use the CCI model to explore the recently released Magical Athlete (Ishida & Garfield, 2025) published by CMYK. The game’s simplicity makes this a relatively simple task, but one that raises some interesting questions.

Magical Athlete is described as “a racing game of pure chaos” that relies heavily on the much-maligned roll and move mechanism. The game is played on a simple track of spaces not dissimilar to classic games like Candy Land. Players draft and select racers, place them on start, and roll dice to see who reaches the finish line first. This is repeated across four (4) races of increasing point value.

But it is important to understand the actual core game loop during play:

Recruit a team: Players use a snake draft to each draft four racers from a ridiculously large pool of options.3 Each racer has it’s own custom meeple, card, and special ability.

Race: Each player selects and enters one of their racers into the race. You may only use a racer once. Racers may not compete in multiple races.

Post-race: Players collect points based on first and second place finishers. The track is flipped to the other side, and a new race begins with new racers.

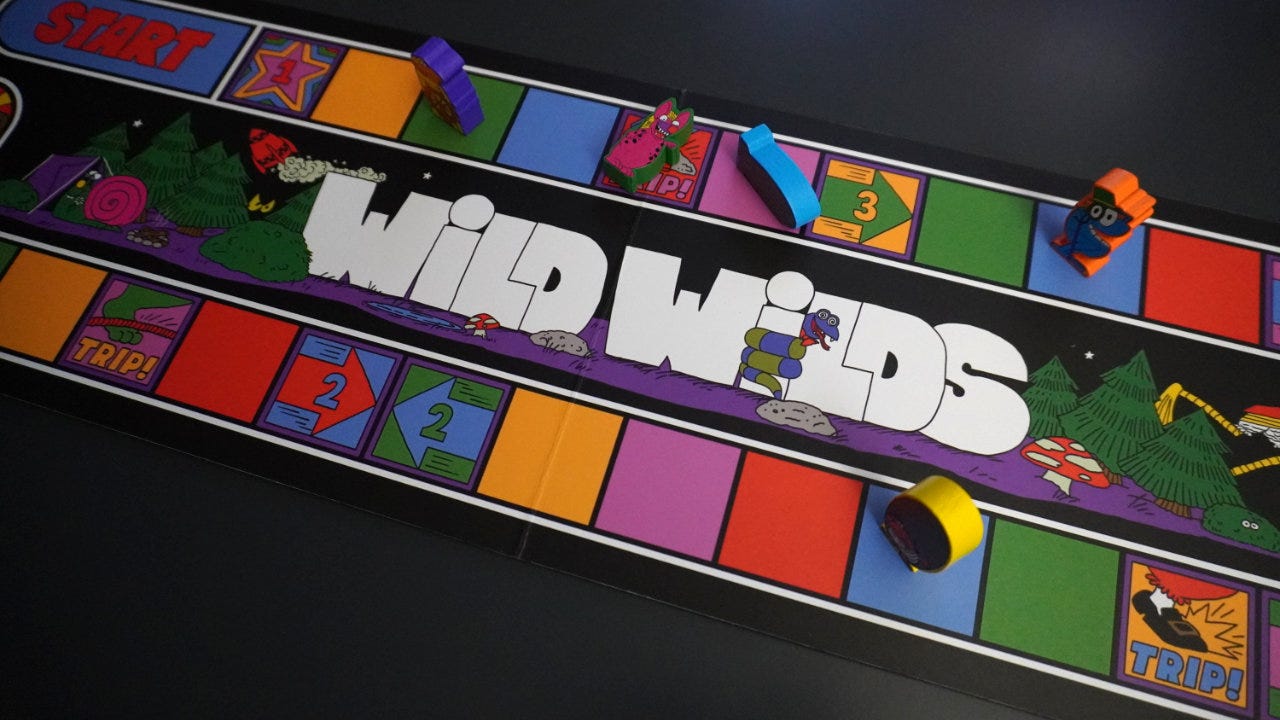

I would argue that the race itself has almost zero player agency. Players take turns rolling the die and moving their racer that many spaces on the track. Depending on the power of the racer (e.g. “Trip any racer that stops on my space.” or “When I stop on a space with exactly one other racer, they’re eliminated from the race.”), the power is only triggered when the conditions are met.

Looking at this through the lens of the CCI model:

Players roll a six-sided die and move that many spaces.

Players trigger their racer’s ability if the conditions are met.

Player advance along the track until reaching the finish.

Choices are not offered. Players largely do not control their actions. There are almost no decisions that impact the game state.4

So other than a few of the racer powers that may be optionally used rather than being mandatory, the race runs itself. Players are rolling dice, moving pieces, but in a form of board game predestination, everything was set in motion at the start.

The only thing left is to see how it all plays out.

But agency isn’t absent. It’s front-loaded.

Candy Land (rules as written) is also a zero-agency game. Players select cards with colored squares, one at a time, and move on the track based on the card selected. It’s a great game when used to teach children how to take turns, the concept of winning/losing, and how to move pieces along a track. Otherwise, I don’t consider it one of my favorite board games.5

So why was Magical Athlete a really interesting player experience when I’ve tried it?

The key difference is that Magical Athlete doesn’t lack player agency completely. It just front-loads it at the beginning of the game and at the start of each race. The very real and meaningful decisions happen when:

Players draft racers with a mix of powers that are offensive/defensive and that increase their chance of winning a given race.

Players select which racer to enter into each race, knowing that later races are worth more points than earlier races.

That snake draft at the start of the game is extremely important to the overall success of each player. Knowing which racer to put out for the low-value first race vs. the high-value final race is critical.

Additionally, it’s an open draft so you know which racers others have selected. Reacting to their selections and choosing a good counter to it is part of the game. Remembering which racers they have remaining in later races creates some interesting tactical choices.

Watching it all play out

So if Magical Athlete has some player agency baked in, but it’s mostly front-loaded at the start of the game, why would the race be fun? Shouldn’t it be just a chore to get it done to see who won?

While this isn’t a review and I don’t claim that everyone would enjoy the game, I do think it’s worth reading reactions to the game. People really seem to enjoy watching the race play out in all of it’s dice-rolling chaos. They don’t seem bothered by the lack of agency, and instead consider the race the “fun” part of the game.

The game taps into a different kind of fun — one in which we build a little system and see what it does. It is the joy of watching a narrative emerge from complex interactions. In the case of Magical Athlete, it’s the mixture of racers, dice rolls, and powers being triggered and interacting.

This is similar, at least in some ways, to the fun of building a massive production network in the Dyson Sphere Program or Factorio video games and just watching it all play out. At some point it’s too complex to know what will happen after it’s built. You just need to sit back and watch it.

Unpredictable zero-agency game phases can be quite enjoyable!

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Zero agency doesn’t mean zero fun: If you simply described a game with a zero player agency phase, I must admit it wouldn’t sound fun. At best, it would sound like a low-fun upkeep phase. But zero agency phases can be really enjoyable if the players built the complex system that is about to play out. It’s a subtle difference, and one worth investigating.

Roll and move isn’t dead: I wrote about outdated game mechanisms in 2023, and had some unkind words for roll and move mechanisms. My opinions have softened in that regard based on games like Magical Athlete, and now I’m more convinced that it’s the implementation that matters.

A unique kind of fun: Again, this kind of fun isn’t for everyone, but apparently it is for me. There is a certain whimsical type of fun of building something and then watching what it does. As an avid fan of Dyson Sphere Program, I’m interested in trying more games that employ front-loaded agency.6

What do you think? Have you played (and enjoyed) games with zero-agency phases or do they just feel like upkeep? Can you think of any other examples of games that tap into this same kind of fun?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

If I had to pick some Knizia games to recommend: Modern Art, Ra, Zoo Vadis, Schotten Totten, and maybe Tigris & Euphrates.

While all player agency models are different, they seem to contain similar core elements. The FADC model proposed in Player Agency and Relevance of Decisions (Thue, et al., 2010) has four items: Foreseeability, Ability, Desirability, and Connection. Chris McDowall’s ICI model has three elements: Information, Choice, Impact. Any of these models is acceptable for tabletop game design, and it’s purely a matter of preference. I happen to like the CCI model and it’s easy for me to remember.

In a snake (or serpentine) draft, turn order reverses each round, so the player who picked last in one round picks first in the next. For example, with players A, B, C, and D, a snake draft might go: A, B, C, D, D, C, B, A, A, B, C, D, and so on.

A notable exception are the racer abilities that include the word “CAN” on them. As per p. 14 of the rules, “If a power ever says you CAN use it, it’s optional. All other powers are mandatory!” So some racers do allow some agency in whether or not to use the power. This feels very close to a Hobson’s Choice: use the power or nothing at all.

If you want to make Candy Land a considerably better game, add just even the tiniest amount of player agency to it. Allow players to draw two cards and play one. You’ll be surprised at how much more fun the game becomes without adding significant complexity.

I recognize that the DSP analogy is not perfect. In that game there is always something to do and no phase where you sit and watch your creation. That said, I do quite enjoy taking a break once in a while and just watching the science matrices flow.

One of my thoughts while reading your article was that Magical Athlete sounded a lot like gambling on horse races, which many people love to do. Players select a favorite horse for different races and if their horse wins, they get excited and earn ‘points.’

A good read. I found it interesting because I've been considering Magical Athlete but have doubted it a bit for this very reason of so much of it being the automated phase without any agency. Whereas in similar games like Camel Up you have the real-time agency of betting in response to the crazy events as they happen before your eyes. In contrast MA seems more like an old-school computer football manager sim where, as you say, the decisions happen beforehand. Those manager games were a lot of fun though! That plus the social side of a group shouting at daft figures I guess are a clever combination.