The Anvil of Probability

Exploring Combat Results Tables (CRTs) and why they endure in game design

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Last week we looked at static and dynamic card markets, and how Pax Renaissance, Pax Pamir, and Canvas all use a modified form of Dutch auction. Mark and Alex pointed out in the comments that Architects of the West Kingdom (2018) and Small World (2009) both have modified Dutch auction mechanisms as well. Great examples!

This week we are exploring Combat Results Tables (CRTs). What are they? Why do they show up all the time in historical wargames? Why are they rarely used in modern eurogames? How do they fit into TTRPGs?

Want to try making your own TTRPG? The Make Your Own One-Page Roleplaying Game guide from Skeleton Code Machine will help you get started!

Successors: Fourth Edition

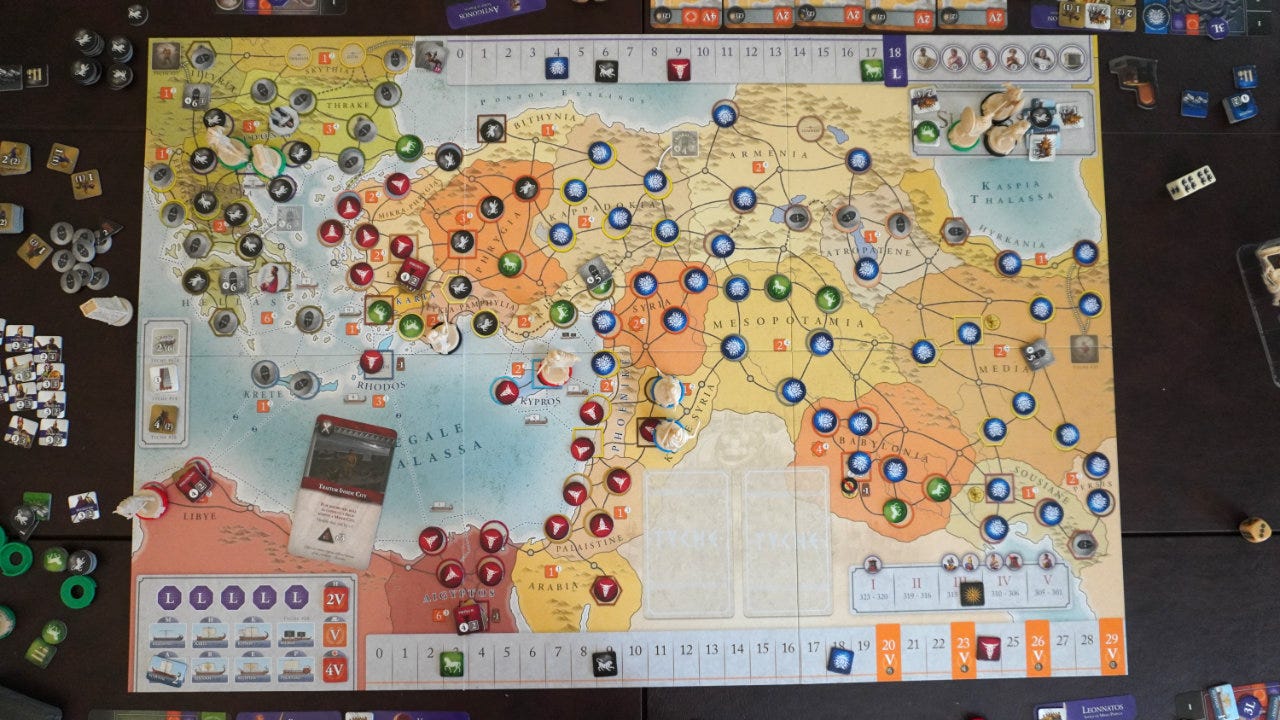

The year is 323 BC, and Alexander the Great has died. Leaving no heir to the throne, his last words are, “To the strongest!” All of Southwest Asia becomes the battleground for Alexander’s warring generals, the Diadoche (Διάδοχοι), all competing to become the successor to Alexander’s empire.

Successors: Fourth Edition (Berg & Simonitch, 2021) uses this setting, the Wars of the Diadoche (322 - 281 BC), to create a long, but interesting strategy wargame. It’s a reimplementation of the first edition game from 1997, almost thirty years ago.

It’s a complex and heavy game. The full rules explanation is all but two hours of videos. Even just the explanation of victory conditions (i.e. how to win the game) is over twenty minutes long!

Some parts of the game feel very fresh, and could have come from a modern euro-style board game. An example would be the use of the Tyche cards that serve as the main core of the game’s actions. Most cards have both a point value (“Operation Points”) and playable action (“Event”) on them. Players choose to spend the points for standard actions, or forego the points to use the event action.

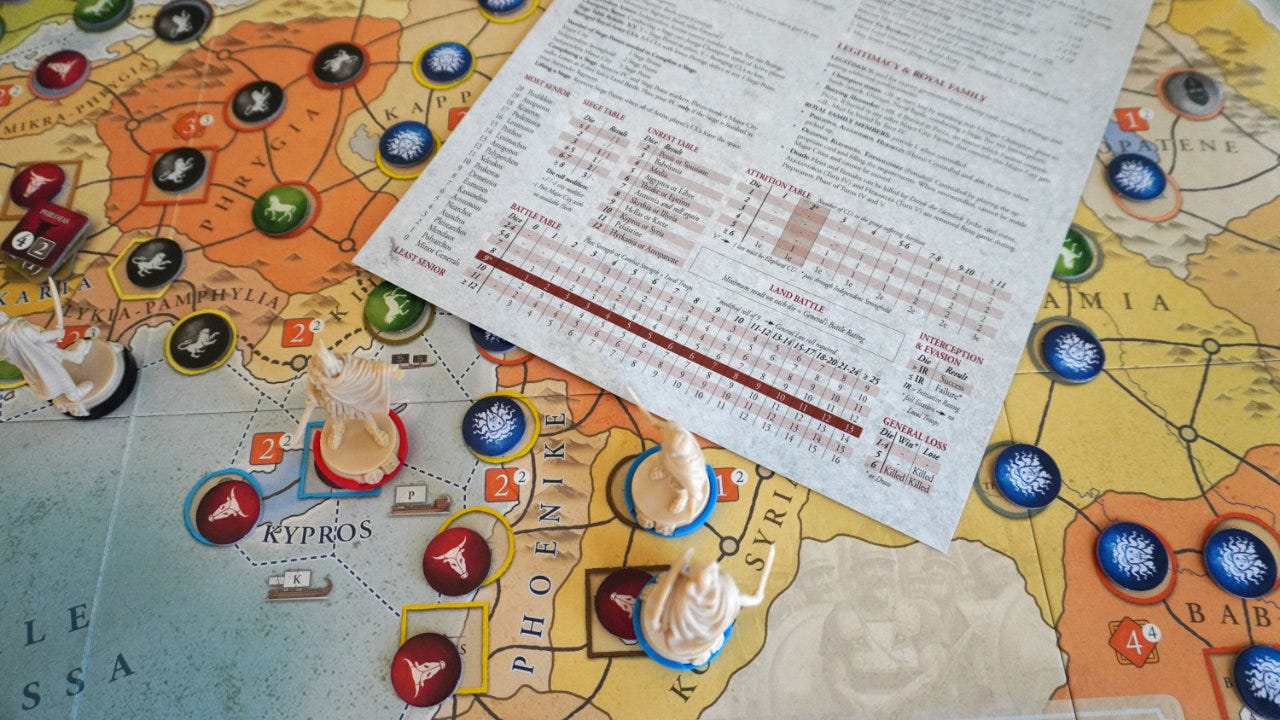

The point-to-point map of Southwest Asia looks like a modern board game, rather than usual hex map of many historical wargames. The latest production from Phalanx even has nice miniatures for the generals, royal heirs, and Alexander’s funeral cart.

At the same time, parts of the game instantly felt like they were from a different era. The part that stuck out to me the most was the use of Combat Results Tables (CRTs).

Combat Results Tables

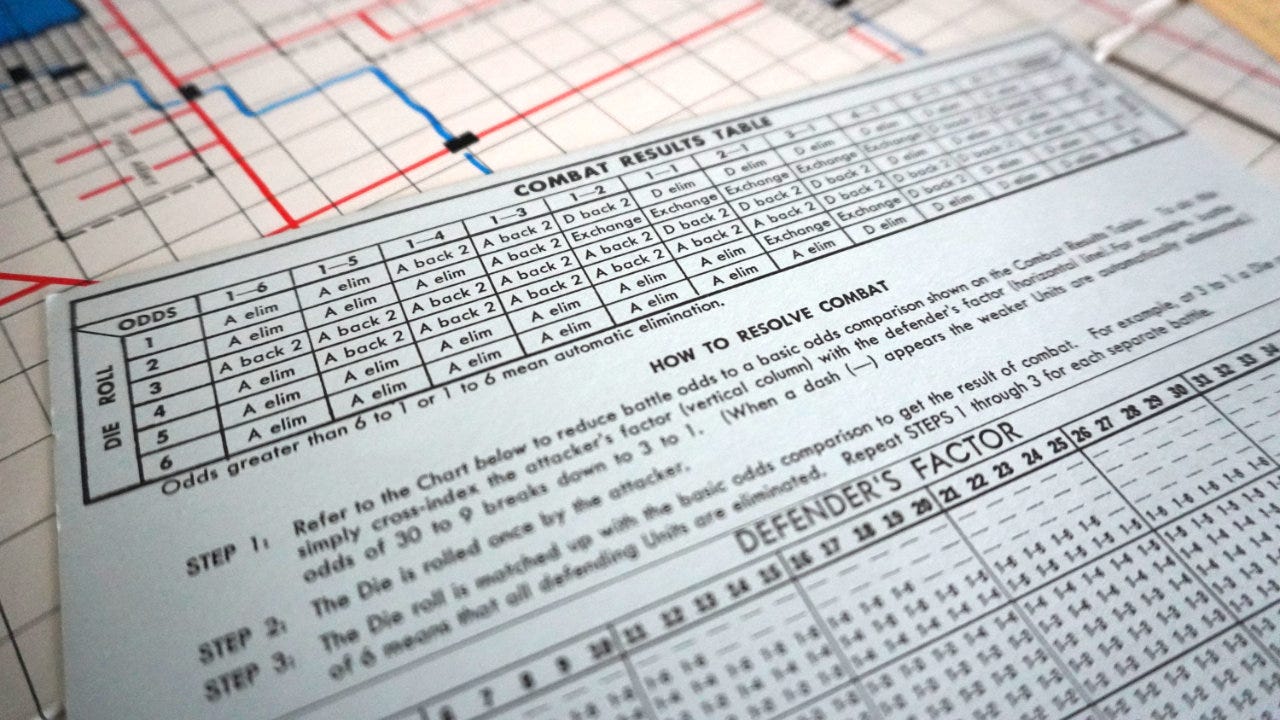

Combat results tables (CRTs) have a long history in strategy wargames. My first exposure to them was probably the diceless Combat Results Table in Tactics II. You look up the strength of the attacker and defender to calculate odds of victory, and then roll a single six-sided die to determine the outcome. It’s a classic implementation of CRTs.

Here’s how BGG describes Ratio / Combat Results Tables:

In many Board Wargames to resolve a combat between units, the Attacker and Defender total the strength of the units involved in that combat. This is then expressed as a "Ratio" (Attacker versus Defender) which is used to index into a "Combat Results Table (CRT)". A dice roll then determines the final result of the combat.

It’s an attempt in wargaming to model the possible outcomes of real world individual combat engagements. It focuses on having a defined “attacker” and “defender” in each conflict, and a relative “strength” for both.

That strength is usually converted into a “ratio” or odds, that can be looked up on a table. Dice can then be used with the ratio to find the combat result (e.g. “attacker eliminated”).

In a simple example from Tactics II, if the Attacker has a strength of 10 and the Defender has strength of 12, this would be a 1-2 ratio according to the chart. Roll 1d6 to get a 5, and then look that up on the Combat Results Table. The result is “A elim” meaning the Attacker’s units are eliminated from the game.

This mechanism makes a lot of sense in military simulation games.

Wargames and CRTs

In Wargame Design: The History, Production and Use of Conflict Simulation Games (Berg, Dunnigan, et al., 1977) there is just a basic assumption that all wargames would have a CRT. There is even a lengthy entry in the glossary describing common combat results (i.e. “the specific possible effects of combat within the game system”) such as:

Attacking Units Eliminated [Ae]

Attacking Units Retreat [Ar]

Exchange [Ex]

Defending Units Eliminated [De]

Routed [Rt]

It lists about fourteen different results, making note that in practice “there are many more results and combinations of results possible in conflict simulation game systems.”

The Complete Book of Wargames (Freeman, 1980) has a similar assumption that all wargames will use CRTs. It explains that “one piece doesn’t simply ‘take’ another just because it moves into the same space, as in chess or backgammon” because “that’s not realistic.” CRTs are what add realism to the game:

If the die is the hammer of chance, the Combat Results Table is the anvil of probability. Very simply, the CRT is a collection of the results of outcomes of battles fought at each of the specified set of odds. … The CRT ensures that the results are not merely haphazard by altering both the outcomes that can occur in any particular column and the odd that any given outcome will occur.

In Successors: Fourth Edition, the CRT tries to simulate the impact of controlling the region of the battle. Attackers and defenders add up their Combat Units (CU), and then add +1 if they control the battle space and +2 if they control the battle province. This value is their Battle Strength shown on the columns in the CRT.

Each side rolls two dice (2d6) and finds their Battle Score. Battle Scores are then compared and the higher score wins completely. The loser’s army is removed from the map. Additionally, if either side rolled a total of nine, they roll again on another table to see if their general was killed in the battle. There’s also yet another table for attrition for some types of troops in the battle.

This finely tuned probability and depth of results comes at a cost. It’s quite a bit of dice rolling and looking things up tables. It does speed up a little with experience, but it will always be a “slow” resolution process by the standards of most of today’s euro-game players.

CRTs and TTRPGs

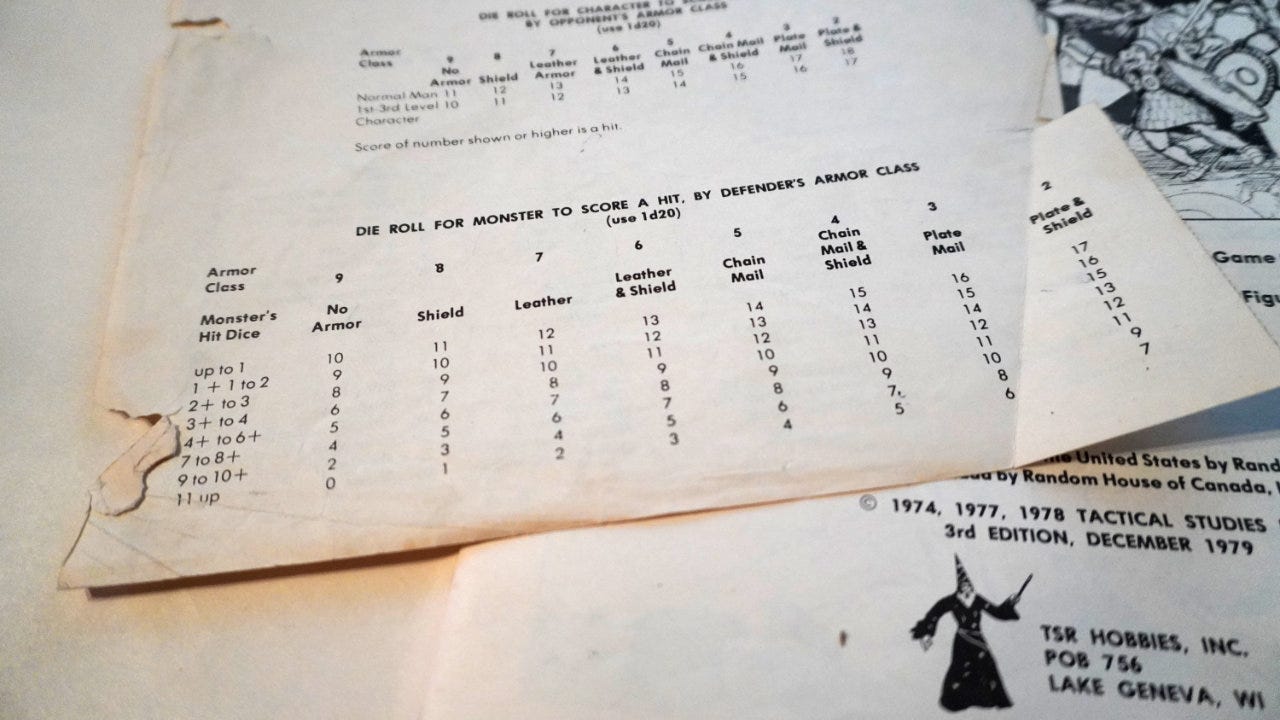

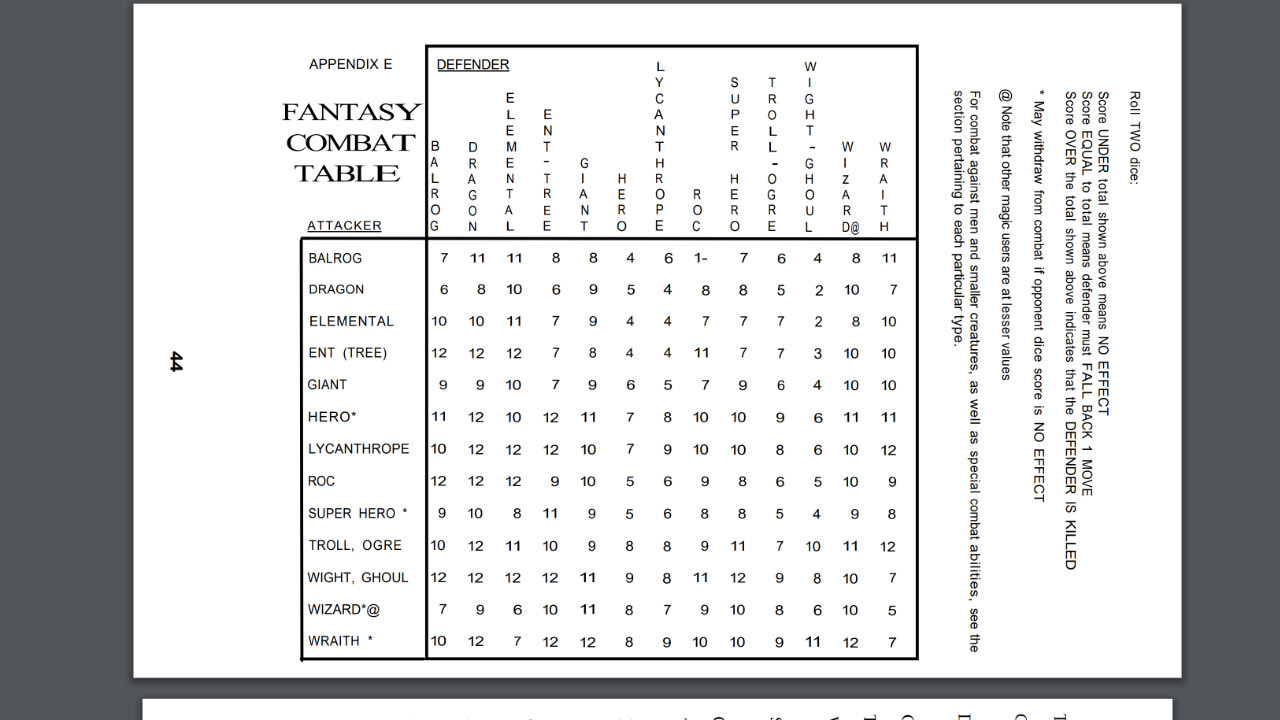

It’s easy to see the CRT roots of Chainmail (Gygax & Perren, 1971) and Dungeons & Dragons in wargaming with their use of combat tables. In the case of Chainmail’s “Fantasy Combat Table”, you look up Attacking and Defending monsters (e.g. Balrog vs. Dragon) and it gives you a target number. Roll under and there is no effect. Roll over and the Defender is killed!

The “Die Roll for Monster to Score a Hit, By Defender’s Armor Class” table in the original Dungeons & Dragons (1974) book works very much like a CRT. You look up the Armor Class and Monster’s Hit Dice and then roll 1d20 versus the target value shown on the table.

Many TTRPGs have moved away from CRTs or CRT-like resolution systems. Target values and either roll over or roll under systems are fast, easy to use, and quick to explain.

Using CRTs in modern games

Since playing Successors, I’ve been thinking about CRTs quite a bit and wondering why they are (a) so entrenched in historical wargames and yet also (b) almost completely absent from modern euro-style board games.

I did a quick check for modern, non-wargame, board games that use CRTs. I failed to find any on BGG. The only exception might be Darkest Dungeon which was listed as having the mechanism, but I couldn’t find anything like a CRT mentioned in the core rulebook. Every linked game on BGG was a historical wargame.

Checking Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design (Engelstein & Shalev, 2022), of the six sample games listed, the most recent is from 1986… almost 40 years ago! Every one of them is a historical wargame.

Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design does, perhaps, give us an answer to my questions above:

The use of the CRT gives the designer a lot of control over potential results. It is possible to have a tightly grouped range of outcomes from one to six or a wild variation. In addition, the designer has many hooks to apply other effects.

Additionally:

While charts can encapsulate a large amount of information and give a lot of flexibility to the designer, they can be intimidating to players and tedious to use and are considered old-fashioned. However, in the right situations, they can be quite useful.

Like any mechanism, there are trade-offs and costs for implementation.

CRTs allow historical wargame designers to have maximum, granular control of battle results. In the quest to have the perfect “simulation” game, this might be one of the best tools available. At the same time, the CRT that gives that control also can bog down the game and be a barrier to new players.

The advent of custom components

I also think that the recent availability of affordable custom components for board games (e.g. cards, dice, tokens, boards, etc.) has given designers additional options that simply weren’t financially realistic in the past.

Deck and bag building games offer ways to adjust probability during the game, but often require a box of cards and components that would have been prohibitively expensive in the 1970s or 1980s. Now, a wargame like Undaunted: Normandy (Benjamin & Thompson, 2019) can use deck-building as a core mechanism with dice and tokens. The CRT is eliminated, the game is streamlined, but I can confirm it still very much feels like a classic wargame in all the right ways!

I’m not sure if reduced manufacturing costs have impacted the use of CRTs, but it is something I’ve been thinking about.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

CRTs give maximum control over probability: I love the “hammer of chance” and the “anvil of probability” phrasing above. There are countless ways to implement CRTs and (like Successors) add in links to more than just battle strength. Terrain, weather, regional influences, and more can all be part of the probability equation.

CRTs come with a cost: All that complexity adds up and has the potential to slow down an otherwise fast game. Wargamers will often say that after a while you’ll memorize the tables and won’t have to check them as often. I’ll just note that even at the end of a 6+ hour game of Successors, we were still checking the table each time.

Modified CRTs are a powerful tool: Not all CRTs need to be complicated. I think there is a place for a modified or simplified version of CRTs that would be a useful tool in a game designer’s toolbox. Like the D&D examples above, it might not be a “true” CRT, but rather have many of the similar elements.

What do you think? Why are CRTs so often used in historical wargames and almost never used in other types of board games? Can you think of examples were CRTs are used in modern TTRPGs? Why can’t I stop thinking about CRTs?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. The MÖRKTOBER prompts have been released for this year! Each day in October, make something for MÖRK BORG inspired by the prompt list and share it. An item, scroll, weapon, class, or anything else. Tag it #MÖRKTOBER.

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

One (probably unintentional?) result of CRT use in a wargame is the "higher level" view the player gets of any particular engagement, more like that of a staff general back at HQ as opposed to an officer in the field closer to the action. Let's look at Axis & Allies, where you have to roll a die result equal to or under a target number to score a hit on an enemy unit. A large battle has you rolling lots of dice in multiple rounds of combat, with you noting each individual hit or miss. There is a certain drama to this, but it lends a "field commander" view to the player, like you are watching the actual fight. CRTs resolve combat with usually one die roll. You don't get any view into the flow of the battle itself, you just see the result. This gives a "HQ" view of the conflict, since you only see the result, not the ebb and flow of the battle. For this reason I have always liked CRTs in grand scale strategic games, but don't like them in more tactical games. Ogre (by Steve Jackson) is an absolute classic, but I don't like the use of CRTs in that game because it is a tactical game of maneuver on a battlefield. I think that if it was developed today, and not in the 1970s, it would not use CRTs at all.

I've been toying with something similar for my NSR game without knowing the terms. A huge benefit is that combat can have many more outcomes than the "they die"/"TPK" binary that D&D combat often end up in.