Roll three, pick two in Rumble Nation

Exploring how simple dice mechanisms can be used to create deep decision spaces in strategy games via Rumble Nation published by Hobby Japan.

Last week we explored induction games and used inductive reasoning to communicate with aliens in Signal from DVC Games. Be sure to check out the comments as we debate the differences between inductive vs. deductive reasoning.1

This week, as MÖRKTOBER begins on Wednesday, we are exploring a simple dice mechanism that leads to some really interesting decisions.

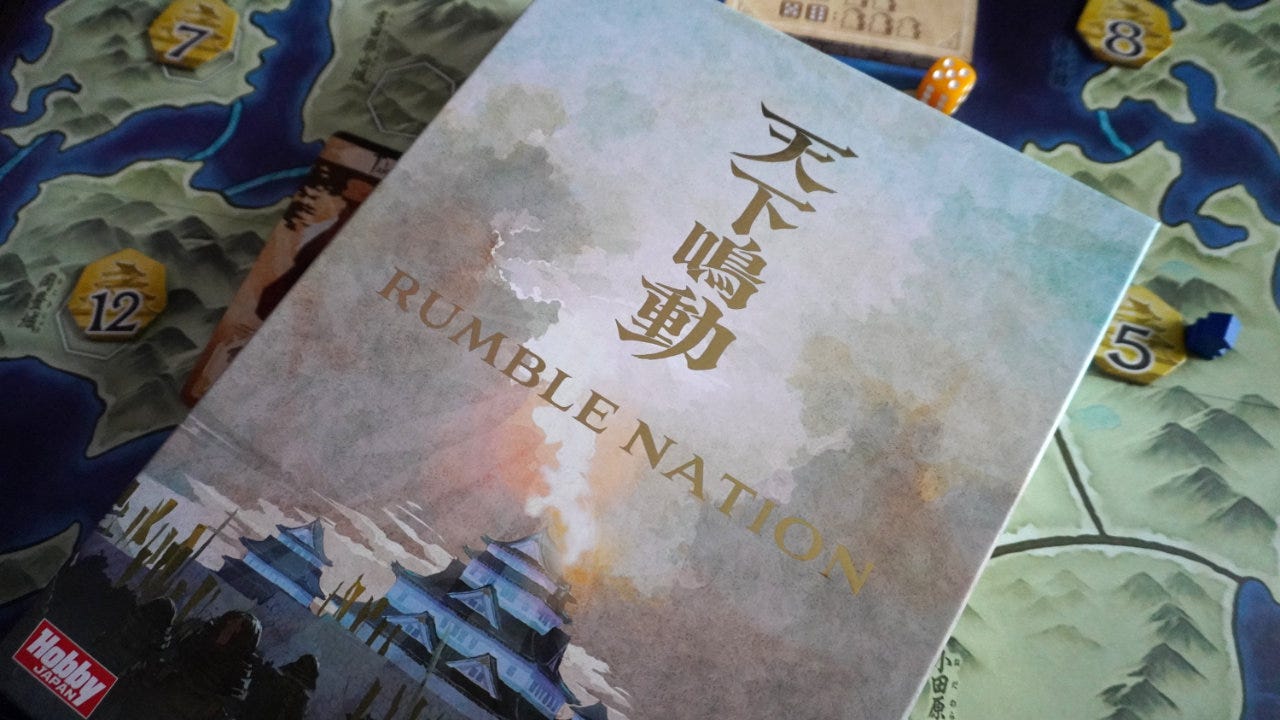

Rumble Nation

Rumble Nation (Shinichi, 2017) was originally released in Japanese as 天下鳴動 (Tenka Meidou).2 It’s now available again with a new English edition released in 2025:

You are warlords during the Sengoku Era, the civil war. Aim for supremacy in Japan by contending for its 11 castles.

While the thematic elements are certainly present, it is largely an abstract strategy game. The board is a simple map divided into eleven areas with various connections between them, not unlike Risk (Lamorisse & Levin, 1959) — it could easily be reduced to a simple network diagram without impacting gameplay.3 The player armies are simple wooden meeples with a slightly larger one representing a daimyo. The castles are randomly assigned tokens with point values on them.

While there’s enough theme there for me, it is not what is the most interesting part of the game. Instead I’d like to explore the simple dice mechanism used to place units on the map.

A game of area control

First, it’s important to understand that Rumble Nation is an area control game. This means that all players may occupy a space on the board, but the benefits (e.g. victory points) are awarded based on proportional presence. In its simplest form, area control means that the player with the most units in a space wins that location or battle.4

Without explaining all the rules, the core game loop works like this:

Chooses one of three actions:

Roll dice to place units

Select and play a tactic card

Use their special daimyo ability

Place units based on the dice roll or resolve the card/ability

The next player starts their turn

This continues until all players have placed all of their units on the board (i.e. 16 soldier meeples and one daimyo meeple). Then, all battles are resolved.

Soldiers are worth 1 strength and daimyo are worth 2. It’s as simple as adding up the forces of each player and the higher one wins.5

Winning an area allows the player to claim the victory points on the yellow castle token. Second place winners gain half that many points rounded down.6

The player with the most points wins.

Dice, soldiers, and daimyo

The way players roll dice to place units is really interesting both in its simplicity and player agency.

The player rolls three six-sided dice together. They then group the dice into two dice together and one separate:

The group of two dice are added together and determines the area where the units will be placed.

The single remaining die determines number of units placed there. Based on a small chart displayed on the game board (1-2: 1 unit, 3-4: 2 units, 5-6: 3 units).

Assuming different values, this allows for at least three options with each roll:

(1+2=3) and (3) → 2 units into Area 3

(2+3=5) and (1) → 1 unit into Area 5

(1+3=4) and (2) → 1 unit into Area 4

It’s important to note that the area numbers are also their victory points (VP). So Area 2 is worth 2 VP at the end of the game. Area 12 would be worth the most with 12 VP.

Because the dice are always grouped into 2-dice and 1-die, the 2d6 probability curve comes into play. Rolling combinations totaling 2 or 12 are very rare, while rolling values in the 6-8 range is quite common. This means that rolling a 2 or 12 is a big opportunity that shouldn’t be passed up, and yet it means not taking the other options available.

There are, of course, times that the dice hate us and we get some really bad rolls. In Rumble Nation, rolling triples (e.g. 2, 2, 2) is a problem because it removes most of the player agency. No matter how the dice are grouped, it will always be 1 unit going into Area 4. It is for that reason, I’d guess, that players are allowed a single re-roll of all dice once per turn.

Reinforcements

I wanted to focus on the dice rolling and selection mechanism of Rumble Nation because I find it so simple, elegant, and fascinating. It could easily be adapted for use in other types of games including both board games and TTRPGs.7

That said, the game is most well known for how reinforcements impact the end of the game. This is a topic I’d like to cover in a separate article, but in general:

After all units have been placed, only then are all battles resolved in order from lowest VP value (2) to highest VP value (12).

If a player wins an area control battle, they place reinforcements in all adjacent, connected areas with a higher VP value where they have at least 1 unit.

This zero-agency phase of the game makes the first part of the game incredibly strategic. Suddenly even low-value areas may be of strategic importance if they can be won, spreading reinforcements to nearby areas. Also, having at least one unit in many areas becomes an important strategy.

Watching the cascade of units across the map is extremely satisfying. Jamey Stegmaier calls this victory overflow.8

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Simple dice mechanisms: On the surface, rolling 3d6 and picking two seems like an almost trivial game mechanism. And yet it creates a really interesting and unique decision space for players. It creates tension both in probability (“Will I roll this value again?”) and timing (“Do I place three units instead of one and go out first?”).

Even light theme is helpful: While Rumble Nation is an abstract strategy game, having some theme there helps to teach and understand the game. While it could be played with just cubes on a network diagram, it would be harder to explain and perhaps significantly less fun.

All areas are valuable: If the game only had the dice rolling and unit placement phase, low-value areas (e.g. 2 and 3) would be ignored. By adding in the reinforcement phase briefly mentioned above, those areas become critically important. It’s an important lesson in applying values to areas in games with area control mechanisms.

What do you think? What are some of the simple dice mechanisms you’ve seen in board games and TTRPGs that are surprisingly deep? Have you tried Rumble Nation either in person or on BGA?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

All I know is that David Hume and Immanuel Kant would be appalled at how the terms are used on BGG.

The translation of the title is interesting. The original Japanese title of 天下鳴動 could be translated as “the whole world resonates” according to Google Translate. The Spanish edition translates to “time of tumult” and the Polish edition is “warring provinces.” I think all of these would be better titles than Rumble Nation which sounds like an Ameritrash dice-chucking game or perhaps a Nintendo Switch fighting game.

For an example of Risk being reduced to a network diagram, see the article on theme vs. mechanisms. It’s one of my favorite examples to use when teaching game design.

I prefer the term “area control” when in reality there are subtle distinctions to be made between area influence, area majority, and area control as strict terms. Most of the time I just say area control and use it to mean any mechanism in that class of mechanisms. If you’d prefer to be more pedantic, check out Geoff Englestein’s discussion in Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design (p. 485-490).

Ties are very common and there’s an interesting tie-breaker mechanism based on which player “went out” first by placing all of their meeples.

I’m increasingly a fan of systems that reward second place victories.

A combat system where two dice determine the hit zone and the single die determines the damage inflicted?

In RPGs:

“A combat system where two dice determine the hit zone and the single die determines the damage inflicted?”

Or the agent rolls 3 dice — one is the damage to the patient, and the (zero or positive) difference between the other two is the damage to the agent. Say I roll 6, 5 , and 1 — I might choose to do 6 damage to the patient and 5 - 1 = 4 to myself, or I might do 1 to the patient and 6 - 5 = 1 to myself. You get the idea.

And of course, the Bakers’ Otherkind dice:

http://lumpley.com/index.php/anyway/thread/759

http://www.lumpley.com/archive/148.html

https://lumpley.games/2022/03/14/otherkind-dice/

Great post as always! I’ve been following for a while, but first time commenting.

This simplicity of arranging dice reminded me of The Great Races by Sid Sackson, where everyone rolls 4 dice simultaneously and secretly groups them into 2 pairs, to move their horses along the 2–12 tracks. It’s just the right amount of agency in such a luck-driven, simple game.