Escalating disaster in crisis management games

Disasters, threats, and losing games… and why that might actually be a fun time!

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Thank you to everyone who commented and shared last week’s Fragile Game Design post. As always, Skeleton Code Machine readers provide perspectives that make me think about the articles in new ways. I really appreciate it!

This week is all about disasters, threats, and losing games… and why that might actually be a fun time.

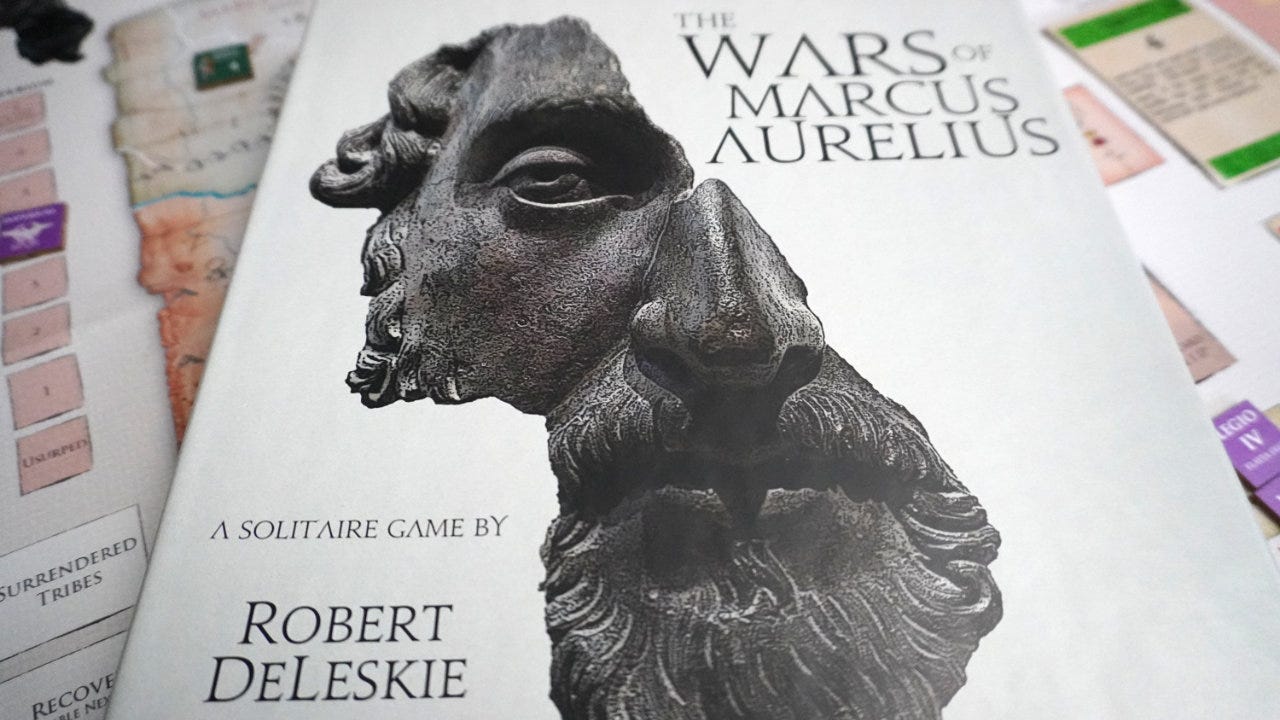

The Wars of Marcus Aurelius

As part of my effort to explore more Hollandspiele titles, I played a couple games of The Wars of Marcus Aurelius (DeLeskie, 2018). It’s a solo-only game set during the Roman Marcomannic Wars which lasted from 170 CE to 180 CE, during the life of Emperor Marcus Aurelius.1 Macromanni, Quadi, and Sarmatian Iazyges tribes are attacking across the Danube River and attempting to march on Rome. You play as Marcus Aurelius, commanding legions and attempting to defeat all three barbarian tribes.2

The game consists of turns, each representing a year starting with 170 CE. Within each turn there are a number of rounds including Spring, Summer, Winter, Fall, and finally an Attrition step.

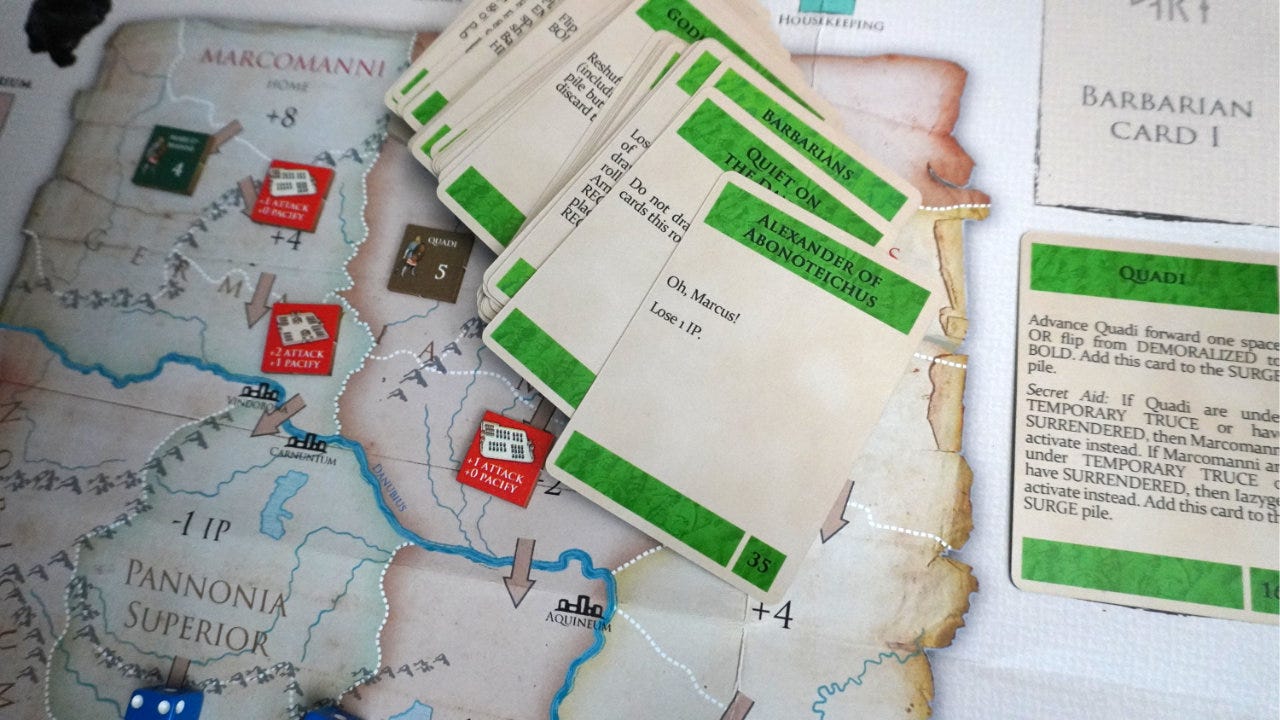

Barbarian Phase: Each season (e.g. Summer), the player draws random cards for the Barbarians which describe events and barbarian actions. The events cause the tribes to advance closer toward Rome, destroy Roman forts, or reduce your Imperium Points (IP).

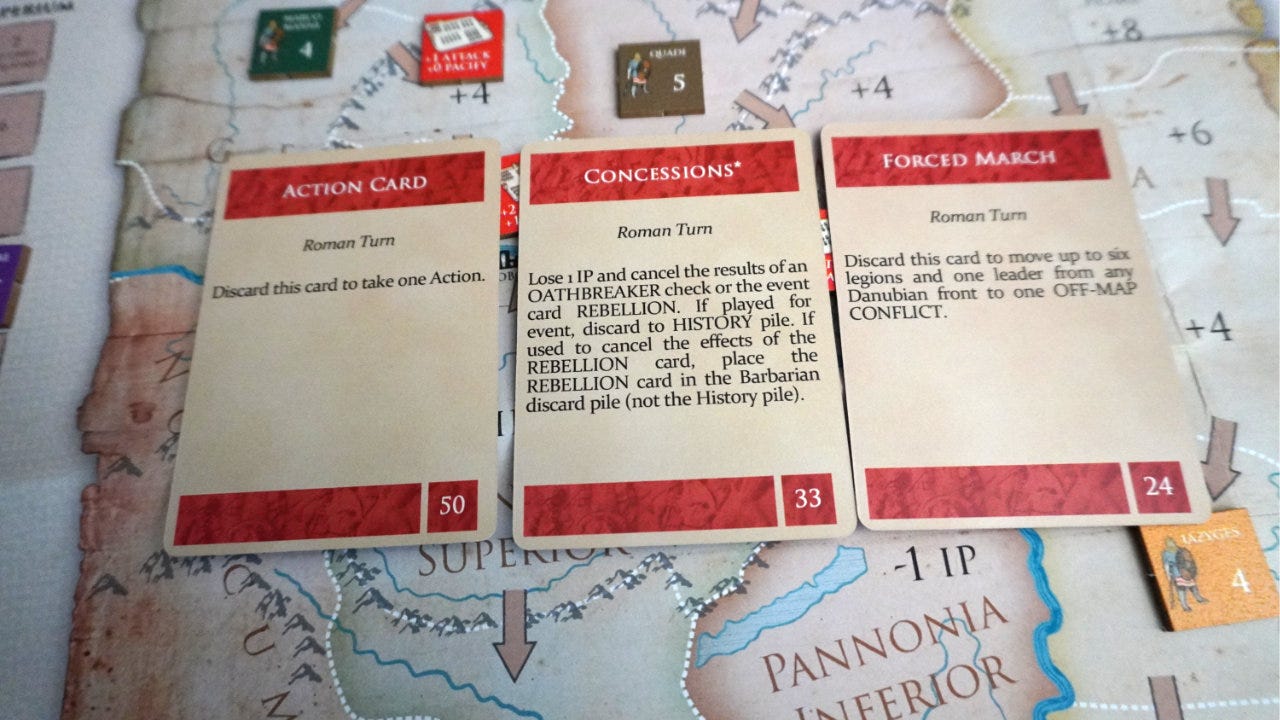

Roman Phase: The Roman side draws a number of cards and then uses them in one of two ways:

Play the event written on the card

Discard the card to take a standard action (e.g. attack, build forts, transfer leaders)

Finally, after all four seasons have been completed, there is an Attrition step where forts without supply lines are removed and other housekeeping tasks. The game then goes to the next year and the process begins again.3

Victory is achieved by forcing all three tribes to surrender before the end of 180 CE.

The Surge

Of all the mechanically interesting things The Wars of Marcus Aurelius does, surges are perhaps the one most worth exploring.

Some barbarian cards are added to one of three Surge Spaces on the board. When the third card is placed, the two tribes who weren’t on the card also activate. This essentially means that all three tribes activate (i.e. move toward Rome) instead of just one. In a game where defeat is always just 4-5 steps away, this has a huge impact!

You can, however, discard one of your Roman cards from your hand to stop the surge from happening. This only prevents the third card from going into the surge space (discarded instead). The very next barbarian card has a chance to trigger the surge again.

It forces a wonderfully tough choice on the player: Do I keep some spare cards to stop surges, or do I spend my cards to attack/fortify and try to survive the surges when they happen?

The gameplay becomes less about launching attacks and winning, and is rather about acceptable losses and hoping for some luck.

Crisis management games

The Wars of Marcus Aurelius immediately reminded me of Pandemic: Fall of Rome (Leacock & Mori, 2018) which happened to be released in the same year. In both games, barbarians are streaming toward Rome from the north. While the mechanisms are vastly different (one is a wargame and one is based on Pandemic), important similarities exist.

Both games are focused on managing crisis and disasters. Each turn you are flipping cards (Barbarian cards in the case of Wars of Marcus Aurelius) and are mostly helpless to watch the bad things happen. The surges feel very much like the outbreaks and epidemics in the original Pandemic.

Finally have your army built up and ready to push the Quadi back over the Danube? Sorry, a plague just hit and you lose some legions (Card #27).

Spent some turns building up forts to strengthen your future attacks? Sorry, barbarians siege your forts and you might lose half of them (Card #37).

Mutiny, off-map conflicts, political issues, and more… all in an unpredictable stream of problems and threats.

Other co-op games that have this crisis/threat management feel include Cthulhu: Death May Die, The Captain is Dead, Spirit Island, Flash Point: Fire Rescue, and Arkham Horror.

The TTRPG example that comes to mind is Mothership RPG. While not every adventure is crisis management, many are. The ever increasing stress and impending panic rolls are comparable to surges and outbreaks. Everything gets much worse in an instant.

The four core elements

At first glance, one would think The Wars of Marcus Aurelius has little in common with Cthulhu: Death May Die, but they both feel like crisis management games. That means we can identify some of the core elements shared between them, and perhaps develop a model for this type of game.

Four core, common elements in crisis management and survival games are:

Pressure: The game exerts steady, constant pressure on the player, forcing them to triage and prioritize problems. There is no time to solve everything and tough choices must be made. This can be either pressure to avoid a surge/outbreak or the threat of the game ending in failure.

Loss conditions: While many games are focused on victory conditions, crisis management games focus on loss conditions. There are many ways to lose the game, but often only one way to win. Pandemic, for example, has one way to win and three ways to lose. The player is focused more on “not losing” than on winning.

Escalation: Cascading problems can make one small problem quickly turn into a giant mess (e.g. surges and outbreaks). Each epidemic card in Pandemic increases the infection rate marker (forcing the end of the game) and spreads more infection cubes, but also intensifies the crisis by reshuffling the discard pile to the top of the deck. Each barbarian card in The Wars of Marcus Aurelius pushes closer to a surge.

Attrition: Much like the loss of forts in The Wars of Marcus Aurelius, crisis management games usually have limited resources or increased burdens as the game continues. Lasting effects from failed panic rolls in Mothership RPG would be an example of this as positive harm accumulated versus a dwindling resource. The effect is that future player actions become complicated or less effective as the game goes on, as opposed to a traditional power progression.

There is a reason that games with these four elements are so popular. The focus on avoiding failure rather than achieving success turns the game into an interesting puzzle to be solved. There is an inherent tension that builds via escalation and attrition that gives the game a story arc.

It can be depressing to lose at these games, but the wins… oh, the wins!

My gaming group still talks about the time we beat Flash Point: Fire Rescue on the hardest difficulty on the very last turn of the game. The pressure was unbelievable, and we all stood up to cheer when we won!

It remains one of my all-time best gaming experiences.

Applying the elements to game design

While there are many games that use crisis management techniques to create extremely fun and popular games, this model won’t work everywhere:

Beware loss aversion: Having too much escalation or too much attrition can lead to players becoming discouraged and unhappy. This ties into the concept of loss aversion that Geoff Engelstein talks about in his Board Game Design and the Psychology of Loss Aversion GDC talk and Achievement Relocked: Loss Aversion and Game Design book. Award a player 5 Victory Points (VP) and they will be happy. Give them 10 VP and take 5 VP away and they will be really unhappy even though the end result is the same. And rare is the player who enjoys XP/level drain effects.

Works better in solo/co-op: When everyone is on the same team as in co-op or solo games, the random Bad Things are handled as a group. What is bad for one is bad for all. In a multiplayer competitive game, it can feel “unbalanced” and arbitrary if one player is hit with much worse events than others.

Also, not all crisis management games need to have all of these elements. Other than losing “remaining time” as a resource, one could argue Pandemic doesn’t really have much attrition.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Crisis management games can be fun: While the idea of just trying to survive in a failing system might not sound like fun, the inherent tension and excitement can make crisis management games really enjoyable. Pandemic is the classic example, but games like The Wars of Marcus Aurelius might also fall into this category.4

A way to think about crisis and survival games: While not perfect (because all models are wrong), these four elements (Pressure, Loss conditions, Escalation, Attrition) provide a starting place for understanding crisis management games. They apply just as much to board games as they do TTRPGs.

It’s a tricky design space: Think about human psychology when designing crisis management games, especially loss aversion and the perceived fairness of random events.

What do you think? What would you consider as the core elements of a crisis management or survival game? Is this a helpful model in a game designer’s toolbox?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. I will be running the Exeunt Press booth at the upcoming Indie & Local Tabletop Games Fair 12 - 5 pm at People’s Book in Takoma Park, MD near DC. There will also be a designer’s panel featuring Elizabeth Hargrave (Wingspan), Tory Brown (Votes for Women), and Connie Vogelmann (Apiary) from 4 - 5 pm. Tickets are free, but you do need to RSVP. Hope to see you there!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

I was reading Jim Dunnigan’s The Complete Wargames Handbook (1980) recently and came across this quote in the “Who Plays Wargames (and Why)” chapter: “The more educated gamer shows a stronger preference for games in the ancient and medieval periods. The less educated gamer leans toward more complex games, spends more hours playing them and for some reason has a strong preference for World War I games. I make no claims as to what any of this might mean.” I also will make no claims as to what that might mean.

The Macromannic Wars lasted the last 14 years of Marcus Aurelius’ life and serve as the background for his Meditations, an important document in modern Stoic philosphy.

As always, there is a lot more to this game than is explained here. The goal is just to give you a general idea of how the game works.

Interesting article. Do you see examples of this in RPGs? I've seen a new brand of 'Play to Lose' RPGs that I find interesting, where they focus on the stories a character makes as they continue their inveitible decline into oblivion.

I appreciate your eye for the essence of a game. You identify the theory and design behind the play and add your own analysis that pushes it forward.

Love these.