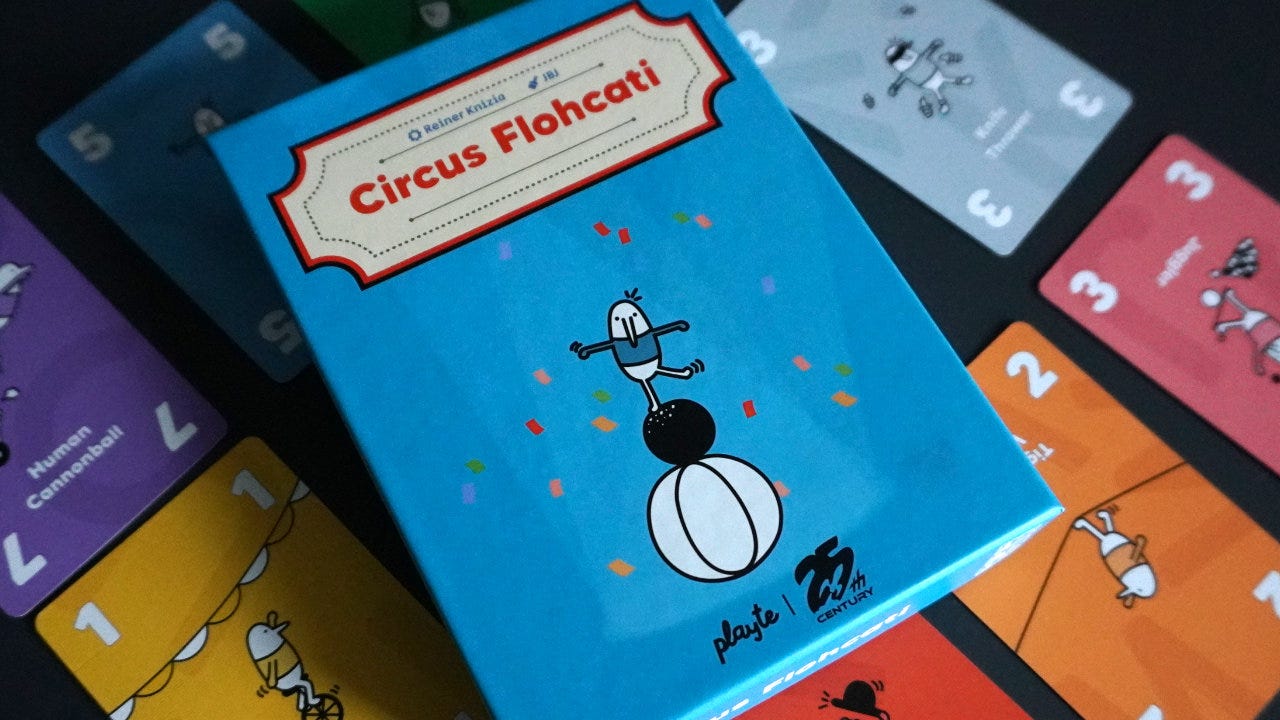

Circus Flohcati: a push your luck card market

Exploring how Reiner Knizia's Circus Flohcati makes an open draft card market feel dynamic without the usual incentives and discard mechanisms. Also, the SCM Annual Reader Survey!

Last week we learned how to make your own TTRPG bookmark, including some mechanisms that use the book itself as part of the game. This coincided with Unknown Dungeon’s TTRPG Bookmark Game Jam that wrapped up over the weekend. I encourage you to check out the 189 submissions to the jam. There are so many creative ideas in there!

This week we are looking at static and dynamic card markets. It’s a topic we’ve explored previously, but Circus Flohcati (Knizia, 1998) has me thinking about it in a new way.1

But first…

Take the SCM Reader Survey!

The 3rd annual Skeleton Code Machine Reader Survey is live. Please take a moment to complete it. Let me know what you want to see more (or less) of each week, and also the best new (to you) game of 2025.

The survey is open now through December 31, 2025.

Static and dynamic card markets

With the creation of BEEP BEEP DANGER and the release of the Turtchester MVP, I’ve been thinking a lot about card markets.2

At face value, they seem pretty simple:

Some number of cards are displayed in a common pool (i.e. market), available to all players.

Players take turns selecting items from the common pool, pulling cards into their private collection (e.g. hand or tableau).

The cards in the market are replaced or refreshed in some way after a player finishes. This could be by drawing a new card or removing old cards.

But as we saw when I last wrote about static and dynamic markets, getting an open draft market right is tricky.

As a refresher, there are two major types of card markets that are defined by how cards are cycled through them:

Static: The cards do not frequently change during the game and/or they only are refreshed when a player takes a card. All cards that will be available during the game are available right from the start. Dominion (base game) is an example of this where the Kingdom Card piles are selected at setup and do not change.

Dynamic: There are mechanisms built into the game to ensure that the market is always changing and refreshed. There can be a large variety of cards in the game and only a subset of the total cards are available during play. Ascension, Shards of Infinity, Pax Renaissance, and Pax Pamir are all examples of games with dynamic card markets.

Of course, many games mix the concepts of static and dynamic markets. The Quest for El Dorado and Ascension are two that immediately come to mind.

The dreaded clogged market

The danger is that a dynamic market (i.e. one in which the cards should be changing over time) can get “clogged” with unwanted cards. This often happens when the market is a fixed size (e.g. 5 cards) and less desirable cards are not purged from the system. Players continue to take the more desirable cards, leaving nothing but unwanted cards in the market. Eventually players are forced to take cards they really don’t want, just because there are no better choices.

This isn’t always a bad thing, but it’s not something I prefer in most games.3

In the case of Turtchester, I wanted binary choices for most decision spaces — two cards in the market and two cards in player hands. Play one of the two cards in your hand, and then take one of the two cards in the market. This led to the possibility of both a clogged market (i.e. one of the two cards in the market was extremely undesirable) and clogged hands (i.e. players might end up with a card they never wanted to play).

One solution (currently in the draft) is that players can choose to draw a random card from the top of the deck. Then, after taking the card, all cards in the market are discarded and new ones are drawn into the display — a drastic but effective way to unclog the market.

The Circus Flohcati card market

Playing Circus Flohcati, an abstract set-collection card game, I was struck by how elegant of a card market mechanism it had.4 In classic Knizia style, it is simple and creates just a touch of push your luck tension.

Here’s how it works:

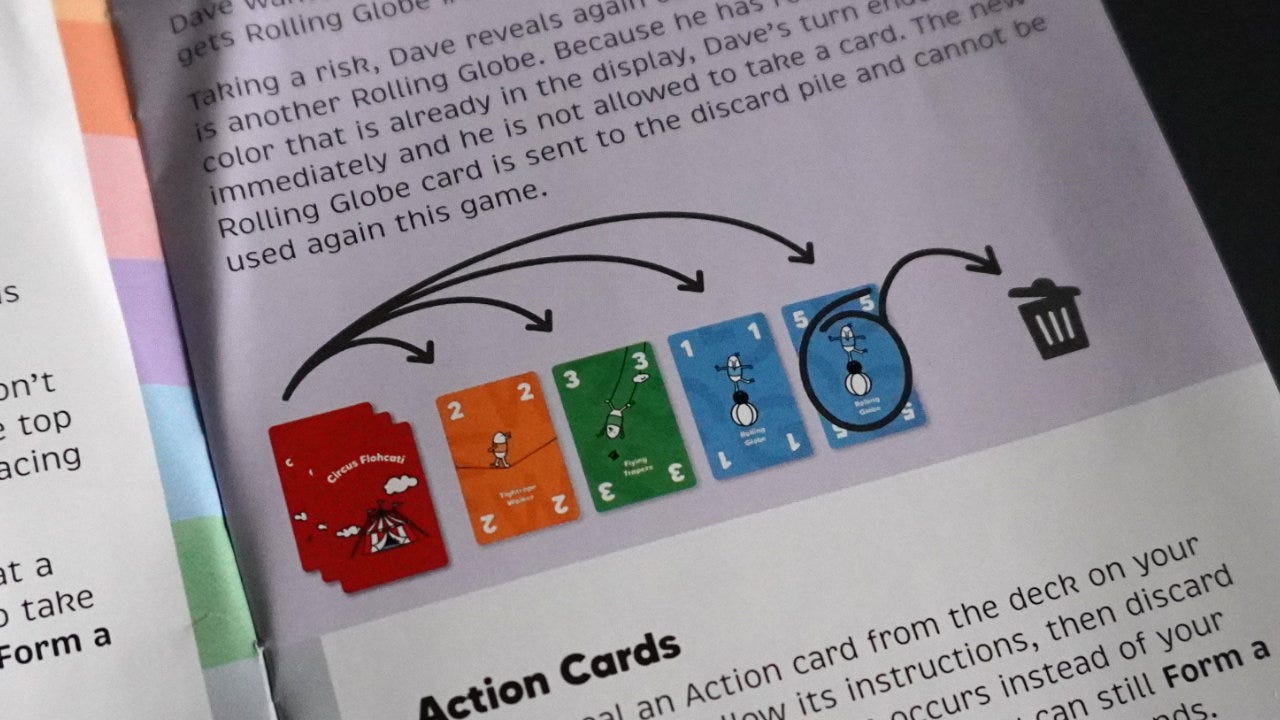

On your turn, you may choose one card from the card market (i.e. “Circus”) from any of the face up cards. The card goes into your hand.

If there are no cards in the market or you don’t want any of the cards, you can instead draw a card from the top of the deck.

The new card is placed into the market and expands the available options of the market — unless it’s the same color card as a card already in the market.

If the new card is the same color, it is discarded (i.e. not placed into the market) and your turn immediately ends. You can’t reveal more cards, you can’t take any cards, and you can’t form a set to score points.5

This creates a player-driven dynamic market that constantly changes in size.

The market might start with one card, but a player might try to push their luck. If lucky, they might be able to draw 2-4 cards to get the one they want. But this expands the market for future players. They will get the benefit of a larger market without any of the risk.

It also depends on the distribution of colors in the market. With a wide array of colors shown, pulling a duplicate is likely and therefore players won’t want to take a risk. But when only a few colors are in the market (even if there are more cards), the risk might be low enough that a player will attempt to draw more cards.

A simple mechanism, but one that increases player agency without adding a large amount of mechanical complexity.

Expanding options, but at a cost

In Dutch auction systems (one of my favorite mechanisms), undesirable options are increasingly discounted until someone eventually selects this. In some games, this discount can even go negative, resulting in the player gaining money/resources for making the purchase. The amount of discount depends on how unattractive the option is compared to the rest of the market.

Circus Flohcati takes a different approach where “bad cards” aren’t discounted. Instead players can choose during any turn to expand the market. They can draw cards and get as large of a market as they’d like… but only up to a point. Each new pull increases the risk of drawing a duplicate color.

You can expand the market, but at a potentially high cost — effectively losing a turn while at the same time benefiting the next player in turn order!

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

There’s nothing simple about open draft markets: Certainly adding a simple card market to a game is easy. The complexity comes when you decide what type of experience you want players to have. If the market is static or dynamic and the size of the market all impact things like randomness and player agency. It’s tricky if you want to craft the best experience possible.

Clogged markets can be a problem: They aren’t always a problem, but I personally prefer a dynamic market. It just isn’t much fun when there are unwanted cards sitting in the market for most of the game. Using discard methods and/or incentives are a way to unclog them.

There are many potential solutions: Circus Flohcati takes an interesting approach to dynamic markets in that it uses push your luck risk management to expand and contract the size of the market throughout the game. It shows that there are countless ways to keep card markets moving and dynamic, beyond the usual methods.

What do you think? Are you OK with unwanted cards sitting in an open draft market or do you feel the need to purge them from the system? Have you seen any other card market mechanisms that keep it moving in ways other than incentives or discards?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want more in-depth and playable Skeleton Code Machine content? Subscribe to Tumulus and get four quarterly, print-only issues packed with game design inspiration at 33% off list price. Limited back issues available. 🩻

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

Circus Flohcati was interestingly reimplemented in 2002 as Star Wars: Attack of the Clones Card Game. This proves that many games can be rethemed as almost anything.

The password to access BEEP BEEP DANGER is “BONEMECH” all caps. The version of “Turtchester” posted there is what I’d call an MVP or minimum viable product. It doesn’t try to be a full-featured game with factions and card abilities. Instead, it’s just the essential core of a game that is playable enough to test.

This can occasionally happen in Ascension: Deckbuilding Game if neither player wants to purchase or defeat certain cards in the market. The unwanted cards will take up some of the six available spots in the market, slowing down the introduction of new cards. As a dynamic card market, this means players will see less variety of cards over the course of the game. Ascension is a well-designed game and eventually forces players to buy cards from the dynamic market if they want a chance of winning. So the issue is not a game-breaking one.

The BGG description for the games says, “In Circus Flohcati, players collect acts from the flea circus to score points, with the game containing ten types (colors) of acts, with acts being valued from 0-7 points.” But the illustrations show little characters with two arms and two legs — surely not fleas. The rulebook in the 25th Century Games English edition (2024) I own makes no mention of fleas. Upon further investigation, it appears the original 1998 German editions did show circus performers as having four legs and two arms — for a total of six. With a notable lack of antenna, I’m not sure they look like fleas.

Wonka: “You get nothing. You lose. Good day, sir!”

Have you encountered the Japanese version of the game, Summer Treasures ? I know it's an abstract Knizia but personally find the theming to match the rules much better.

For those that haven't you are collecting treasured memories of a summer holiday. The fact that only the "better memory" will score and that you can't have two memories of the same type in the market feels much more intuitive. Plus doesn't hurt that the art is beautiful!

In the original star realms it is "solved" by almost always having cards that are good enough to buy.

It fees however really awful if no player in a market want's to buy something.