The dice game inside Before the Bog God

Exploring how Before the Bog God by Infinite Citadel uses a two-player dice game as a framework for telling a story about wishes and old gods.

Last week we looked at how A Place for All My Books uses both personal and shared player boards to create a cycle of worker placement actions. Over at Exeunt Omnes, there was update on Epsilon and how it will use a pointcrawl map.

Nominations for The Bloggies are open through January 31, 2026. I’d truly appreciate your support by nominating a Skeleton Code Machine article. Anything written between December 1, 2024 and December 31, 2025 is eligible.1

This week, we are making wishes and performing rituals with Before the Bog God by Infinite Citadel.

Before the Bog God

I backed Before the Bog God when it was on Kickstarter, and it recently arrived.2 Written by Andrew Beauman and Matt Best of Infinite Citadel. It’s a slim, 25-page “duet ritual game of cunning, corruption, and cosmic bargains.”3

One player acts as The Wisher who wants to claim a wish or some other unspoken bargain with the opposing player. The other is The Old God, presumably the Bog God of the title, but might also be a “smirking leviathan” or “winged aberration.” Together they will perform an adversarial ritual — almost like a negotiation.4

The two players assume these roles and perform some setup:

The Wisher rolls six dice and places them in a row.

The Old God gets three dice to start which are kept hidden, and gets a chance to swap two of The Wisher’s dice.

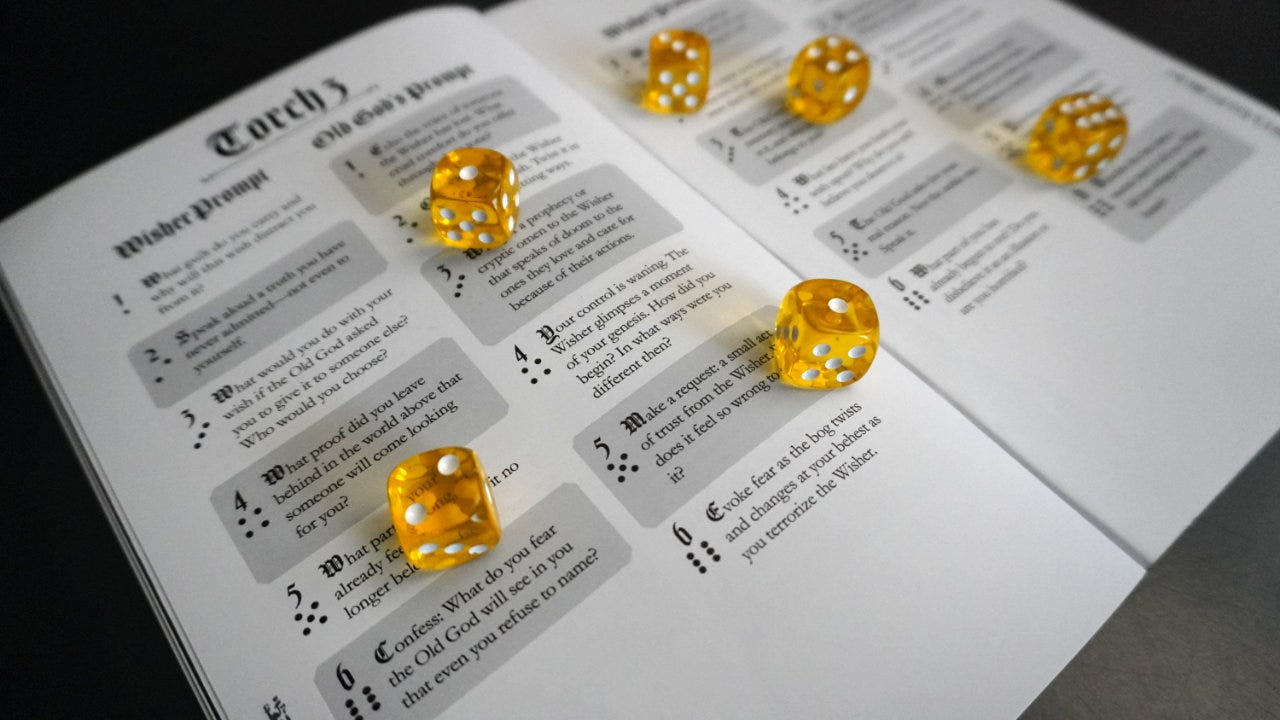

With that, the game begins. Players alternate taking turns in which they perform one of their possible actions and respond to a narrative prompt.

It’s a back and forth competition using a rather interesting dice mechanism.5 The Wisher wants to seal (i.e. lock in) all of their dice with one pattern. The Old God wants to thwart this by sealing in the wrong pattern.

The Wisher

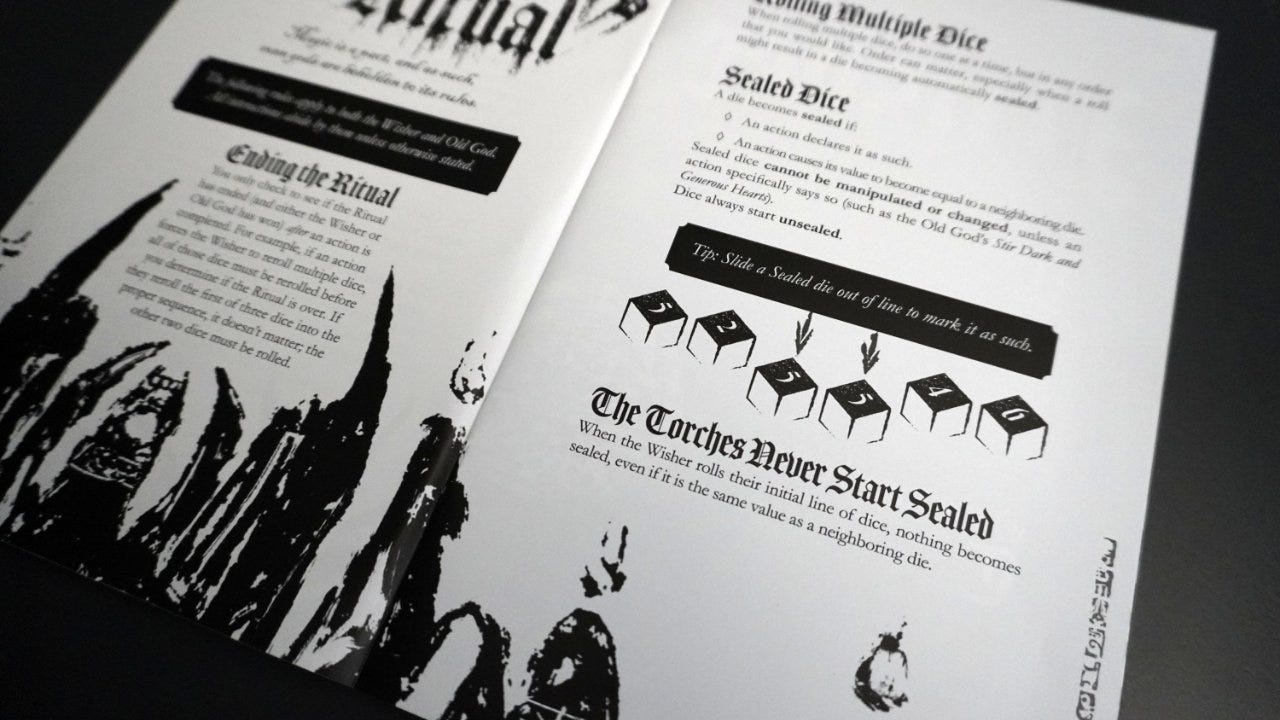

The Wisher needs to seal all of their dice in a specific sequence. All dice must be within 1 pip of their neighbor: greater than by 1, less than by 1, or equal to their neighbor. Dice are sealed (i.e. shifted out of the line and locked) when they are equal to their neighbor. For example, if two adjacent dice are both sixes, they would be pushed out of line and sealed for the rest of the game.6

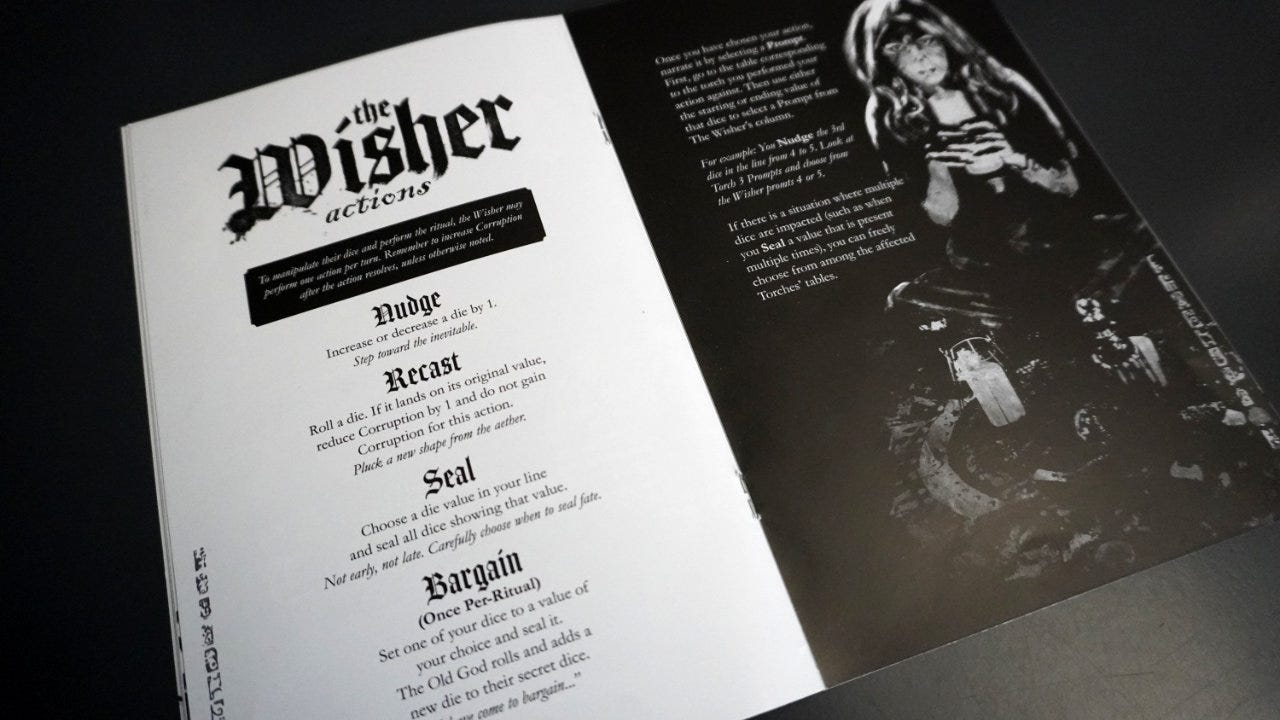

To do this, they can perform a few different actions:

Nudge: Modify a die by +1/-1.

Recast: Re-roll a die.

Seal: Seal all dice with matching values.

Bargain: Once per game, set a die to a value and seal it.

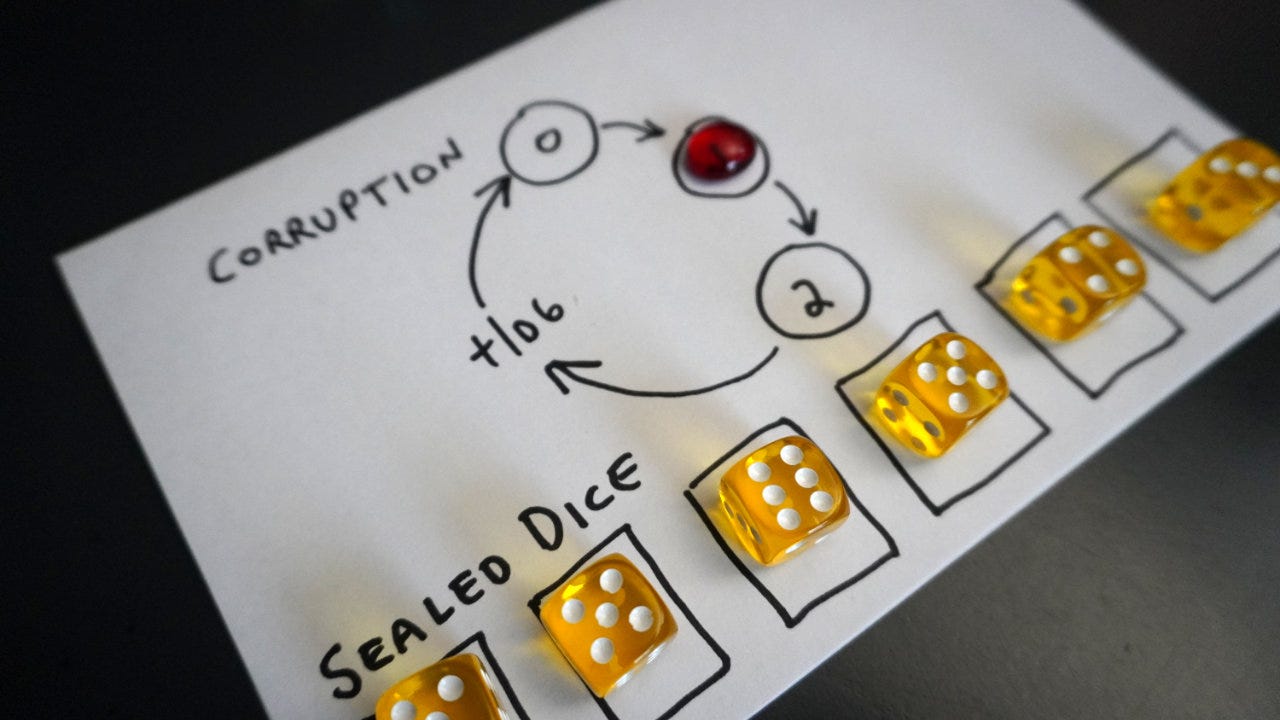

These actions are not free. Almost all of them increase your corruption. Once corruption hits 3, it resets back to 0, and The Old God gain another die to use.

The Old God

The opposing Old God wants to prevent The Wisher from completing the sequence described above. They win if they manage to seal The Wisher’s dice in any sequence other than the desired one.

Like The Wisher, they have a few actions they can perform to accomplish this:

Stir Dark & Generous Hearts: Unseal a die and change it to a six.

Bide Thy Time: Modify one of The Old God’s dice by +1/-1.

Equivalence: Increase one die by 1 and decrease another by 1.

Baleful Transformation: Force The Wisher to re-roll some of their dice.

Wither: Decrease one die by 2.

Much like The Wisher’s actions, these are not free. Most of them require spending a die, removing it from the game. Some require a specific value to trigger the action. The only way to gain more dice as The Old God is to wait for The Wisher to increase their corruption.

A dice game wrapped in chthonic ritual

One thing I appreciate in solo (or duet) TTRPGs is when they have a mechanical core that is so well crafted that it almost stands on its own, regardless of the narrative and storytelling elements that make the game what it is. Meaning if you strip the game of its theme, would the underlying mechanical bones still be kind of fun to play.

Inside Before the Bog God is an interesting little dice game. Even if the ritual prompts are ignored, it retains an element of competitive fun. I could see this being played much like the other traditional dice games I described during Dice Week.

This doesn’t mean the underlying game needs to be perfectly balanced and finely tuned like a board game.7 But having a core that is still fun to play when stripped of theme is a really good indication that the overall game will be a good experience.

A more accessible type of game

This can be important because not everyone is going to be willing or able to roleplay at the same level. Some players will easily step into the role of The Wisher or The Old God and have no problem crafting a story based on the provided prompts. Other players may, however, struggle when facing a prompt — their mind going blank at the thought of how to advance the story.

By having a good mechanical core, there is a chance the game becomes more accessible to both types of the player — the seasoned roleplayer and the shy newcomer. They can both feel like they are participating in the mechanisms of the game fully, even if not in the narrative storytelling.

Not every game needs to meet the needs and expectations of every player. It’s OK to make games for talented and experienced storytellers. But it’s also nice when there are games that might be an easy entry point for new players of the genre.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Check the mechanical core of your game: This is obvious and a necessity when designing a board game or card game. It’s less obvious when making a storytelling game or TTRPG. As an exercise, try to see how the game plays with some or all of the storytelling elements (e.g. narrative prompts) skipped or removed.

Duel/duet games are popular: If you follow board games, you’ve seen the recent explosion of “Duel” versions of seemingly every popular game. It’s hard to get a group together to play, and solo games have filled some of that gap. Duet games expand that player count a little bit, allowing it to be easily played with a partner or roommate.

Consider solo play in duet games: I was actually able to run through Before the Bog God as a solo game and it was still an enjoyable experience. The key challenge is when there is hidden information in a game, which there is in this one. So while knowing the values of The Bog God’s dice did change the game a little, it didn’t break it. If you make a duet game, consider what changes need to be made for players to try it solo.

What do you think? Are there any other duet TTRPGs that you’ve played and enjoyed? How do you feel testing the mechanical core of a game separate from the theme? What bargains have you made with The Old Gods?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Want more in-depth and playable Skeleton Code Machine content? Subscribe to Tumulus and get four quarterly, print-only issues packed with game design inspiration at 33% off list price. Limited back issues available. 🩻

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

If you want a suggestion: Everything is Pointcrawl or Playing the Chaplain’s Game.

The project raised $1,640 with 92 backers on Kickstarter.

I’ve noticed that 2-player board games will often use the term “duel” in the title while 2-player TTRPGs will often say “duet” instead. I use the terms interchangeably in this article.

In some ways, Before the Bog God reminded me of Binary Star’s Fey Contract Law contribution in Tumulus Issue 5. If you are a Tumulus subscriber, go back and check that one out. If you missed it, there are still some back issues available at the Exeunt Press Shop.

The dice mechanism of Before the Bog God is the mechanical core of the game, but it is a narrative TTRPG. I’m intentionally skipping over the prompts which make up a large part of the zine because, while the most important part thematically, I’m exploring just how dice are used in the game.

This isn’t a full rules explanation. There are a few exceptions to this where dice can be unsealed and/or modified as part of the game.

I think there are some ways a player could exploit the fragility of the design in Before the Bog God. For example, if The Wisher seals multiple dice at a value of 6, it effectively disables The Old God’s Stir Dark & Generous Hearts action. They can use it, but because they can only change a die’s value to 6, it has almost no effect.

Thinking about this statement in your footnotes ( always love the footnotes BTW)

*“The Wisher seals multiple dice at a value of 6, it effectively disables The Old God’s Stir Dark & Generous Hearts action. They can use it, but because they can only change a die’s value to 6, it has almost no effect”*

Is that strictly true? Because Stir Dark… also unseals a dice as well as turn it to a six, doesn’t it mean that other powers could then be used on it subsequently since it is no longer sealed?

In depth summary of mechanics and the game. Thanks!