Ten lessons from five more games

You can learn something from every game you play. I played 18 board games over the weekend and here are my observations.

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, an ENNIE-nominated and award-winning weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Check out Public Domain Art and Fragile Games to get started. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration delivered to your door each quarter!

Last year I published Ten Lessons from Five Games after a weekend of gaming. Having just finished another weekend of gaming, I thought this might be a good format to use again. We played 18 different board games, including quite a few games that were new to me.1

As before, it got me thinking about the design of each game: What made the games fragile? Did the mechanisms support the theme? How did it employ player agency?

So this week, we look at five of the games played and find a useful lesson or tip from each one!

Bus

Bus (1999) is a Splotter game about building bus routes and delivering passengers to their destinations — and sometimes stopping time, resulting in the destruction of the space-time continuum.2

Emergent maps: The city board for Bus is always the same, but players customize it even before the game begins by placing the location tokens. Then, based on where more tokens are added, each player extends their bus routes. This organically creates routes to reach a mix of offices, bars, and homes. It was fascinating to watch it develop during the game.

Stingy points: It’s not uncommon for modern board games to have winning scores in the 30 - 100 VP range. Bus is odd in that much lower scores are more likely. Each point might take multiple rounds and a lot of effort. Our final scores were all under 10 points per player.3

This is the game I’ve been thinking about the most since the weekend. It was filled with extremely tough decisions and I desperately want to give it another shot.

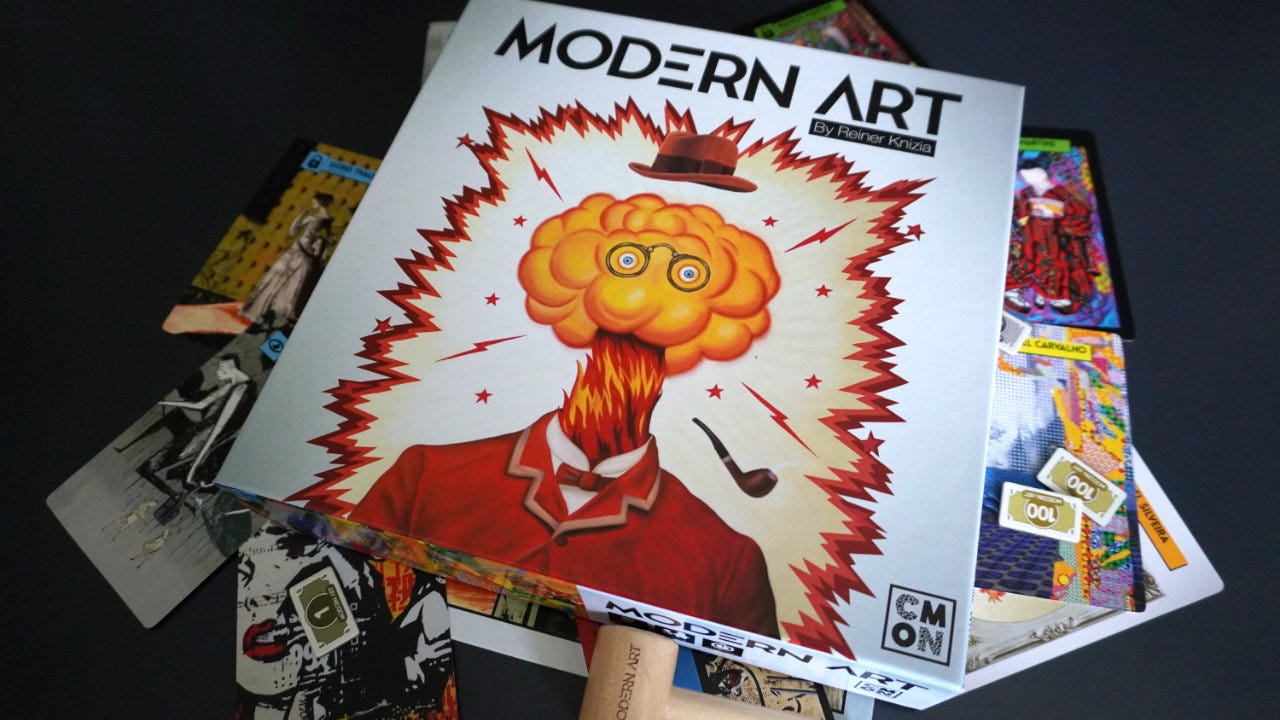

Modern Art

Modern Art (Knizia, 1992) is a auction/bidding game about buying and selling paintings. Players take turn auctioning art pieces shown on cards:

Many types of auctions: Modern Art uses four types of auctions: open, one-offer, hidden, and fixed price. They are tied to the art pieces and are therefore part of the decision a player needs to make when offering something for sale. Sometimes a hidden auction (i.e. closed-hand, simultaneous reveal) is best and other times an open (i.e. “Going once! Going Twice!”) is best.

Converging value: At the start of the game, bids are all over the place — particularly in hidden auctions. One player bets 5 and another bets 56. By the end of the game, players collectively learn the value of each artist and bids become much closer, often separated by only 1 or 2 dollars.4 I find it really interesting to watch people hone their skills in valuation as the game progresses.

I’ve only played Modern Art a few times, but it’s been an amazing experience each time. Reading the rules, it doesn’t sound like that fun of a game. Given the right group of players, however, some of the auctions become laugh-out-loud funny.

Ostia

Ostia (Chuo, 2022) is about trading in the ancient Roman port of Ostia. Perhaps not the most intriguing theme, but the game does some interesting things:

Rondel x mancala: I wrote about rondel x mancala games before, using Crusaders: Thy Will Be Done as an example. Ostia uses a similar mechanism, but combined with track movement on a board. It’s a good combination.

Unforgiving games: Some games include catch-up mechanisms and ways for players who make mistakes to stay in the game. Ostia felt like a tight puzzle — one where you could really back yourself into a corner of the rondel. I’m not sure how I feel about that, but it has me thinking about it quite a bit.

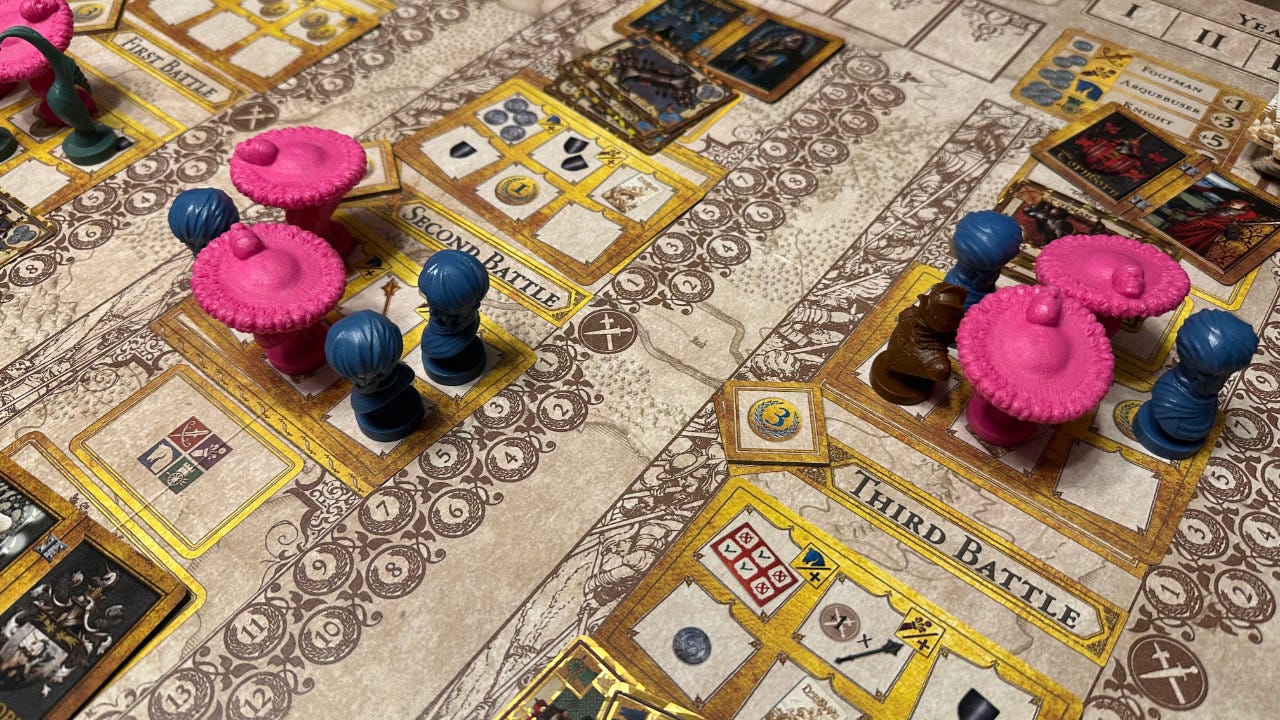

Dogs of War

Dogs of War (Mori, 2014) is a favorite of SVWAG and a game I’ve wanted to try for a while. Players deploy their private armies to support various houses, hoping to back the winning side:

Tug of war: I’ve written about tug of war mechanisms before, and mentioned how Star Wars: Shatterpoint (Shick, 2023) uses a shrinking tug of war. The tug of war in Dogs of War feels more like betting or wagering on the winner. There are even some cards that allow you to bet on both sides.

Game arc: I thought it was notable that while Dogs of War is effectively the same thing (mechanically) four times in a row, each of the four “years” in the game felt different. It created a game arc in a way that the one I mentioned in a previous article did not — each round provided more coins to buy more armies to use with more captains.

After seeing the tug of war mechanisms in Dogs of War, Star Wars: Shatterpoint, and The Lord of the Rings: Duel for Middle-earth, I’ve really fallen in love with it. They demonstrate the different ways to trigger each side and how to visually represent it.

Euphoria: Build a Better Dystopia

Euphoria: Build a Better Dystopia (Stegmaier & Stone, 2013) is a game I played a lot when it came out over a decade ago, but haven’t played recently. Was good to get it back to the table:

Dice placement and losing workers: Actions are selected using a worker placement mechanism with dice workers (i.e. dice placement). Thematically, as workers’ knowledge increases, they are more likely to leave. Mechanically this means rolling your worker dice as they are recalled and losing one if the total is greater than 16. Creates some interesting decisions about how and when to recall workers, something that can otherwise be boring.

High player count: Many euro-style, worker placement games bog down at higher player counts — most are best at three players. We played Euphoria with six players and it moved along quickly. Downtime wasn’t too bad. My guess is the lack of churn (i.e. game state changes) between turns helped with this. As did the ability to “bump” opposing workers out of spots, so you were never truly blocked.

The game has a tongue-in-cheek dystopian theme. Project tiles have names like Registry of Personal Secrets, Cafeteria of Nameless Meat, and Center for Reduced Literacy. There is a Worker Activation Tank to gain more workers (dice) that requires either a “shock” or a “fresh blast of water” for the worker.5

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

You can learn something from every game: I’ve said this many times, but even “bad” games can teach you important game design lessons. Luckily we didn’t play any games I didn’t enjoy, but each one did something interesting. If you want to be a game designer, there is no better teacher than playing a ton of games.

Board game fluency matters: We played with experienced players, all of whom were able to pick up new rules quickly. This is because they possessed “board game fluency” — an understanding of many of the core mechanisms. They could instantly recognize things like, “Oh! This is just worker placement.” Might be a good topic for a future article.

Theme vs. mechanism: Some games like Ostia felt abstract (i.e. loose connection between theme and mechanism). Bus, on the other hand, felt quite thematic in how passengers left home, went to work, went to the bar, and then back home. Routes needed to be created to link all three places. A good exercise would be to identify the layers of theme in each game.

That’s ten tips from five games. Which one do you think provides the most game design inspiration? Let everyone know in this week’s poll!

— E.P. 💀

P.S. I’m working on a companion guide to Make Your Own One-Page Roleplaying Game called Make Your Own Tabletop Roleplaying Game Adventure. Follow Exeunt Press on Bluesky to see some WIP screenshots.

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

The weekend H-index was 2, meaning we played 2 games at least 2 times each. All other games were played only once. The most played game was A Fake Artist Goes to New York (Sasaki, 2011) at 6 plays. It’s a very short game.

Splotter is a Dutch game design collective. The BGG description says they make the kind of games that elicit reviews like this: “I simply cannot wrap my head around how this game is supposed to work. I played with a couple guys who think it's amazing, but I can't keep track of things, and every time I thought I had a strategy it would all come toppling down at the first hint of interaction with other players.”

I assume final scores would increase with more plays, but would still be low.

Technically the game uses money tokens that represent thousands of dollars, so a 1 would actually be 1,000 dollars.

Included with the official Rules and Other Public Files for Euphoria is a folder of fan-fic backstories. I have not read them… yet.

This is because they possessed “board game fluency” — an understanding of many of the core mechanisms. They could instantly recognize things like, “Oh! This is just worker placement.”

This reminds me of video game fluency. I can't explain how I know the game wants me to go in a certain direction, I just know it does.