Dungeon: the first adventure board game

Exploring what makes Dungeon! an enduring game of exploration and adventure

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

This is the first in a three-part series about classic TSR board games from the 1980s. Don’t miss Part 2 - Fantasy Forest and Part 3 - D&D Computer Labyrinth Game.

Last week we looked at negative optimization strategies in Undaunted 2200: Callisto, a game that was just released. This week we are looking at a game first released almost fifty years ago… Dungeon!.

It’s a game for which I have a nostalgic love, but also one that was amazingly innovative for it’s time. It’s worth exploring, and there are important things we can learn from its design.

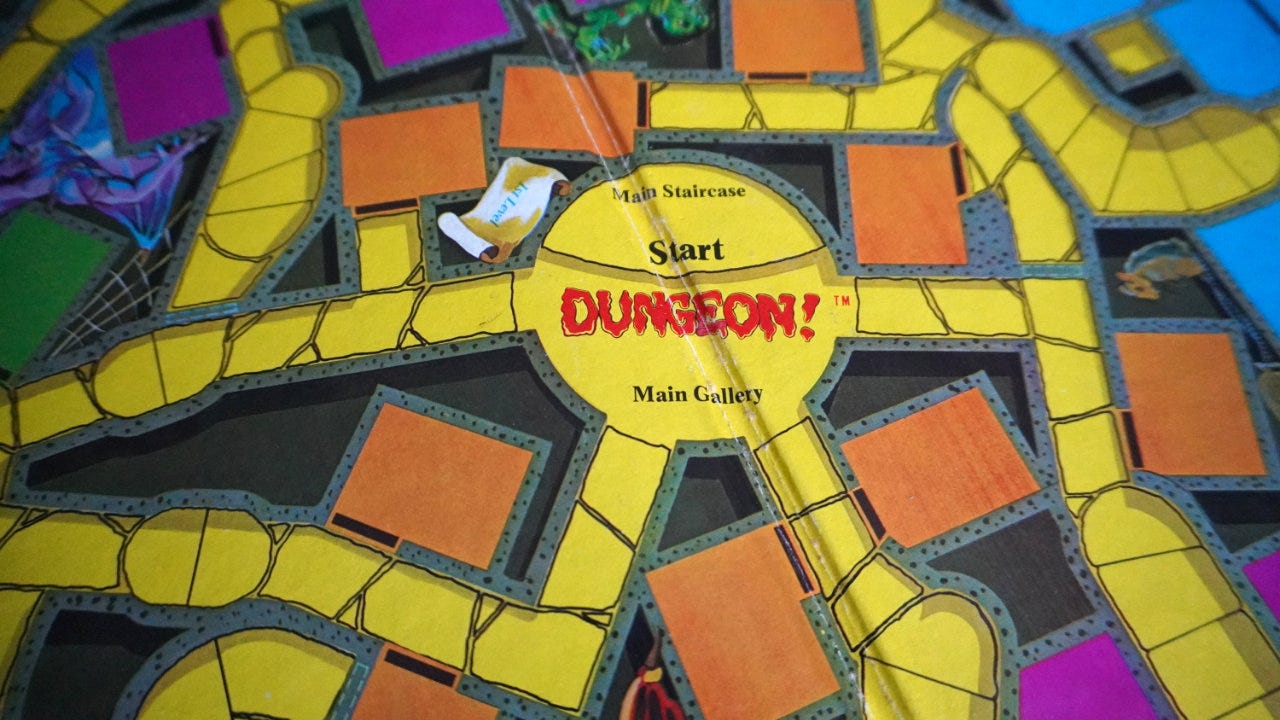

Dungeon!

Dungeon! (always stylized with the exclamation point) has an interesting history for those familiar with TTRPGs.1 David Megarry, the designer, was a member of MMSA and the Twin Cities Blackmoor groups along with Dave Arneson, who would go on to be one of the creators of Dungeons & Dragons.

Arneson ran their Blackmoor games and complained about being the all-time GM. He wanted a break where he could just be a player — a tradition that continues to this day.2

So in 1972, Megarry worked on making a GM-less board game that would capture the feel of Blackmoor. Originally called The Dungeons of Pasha Cada, it was rejected by Parker Brothers for publication but picked up by Gary Gygax and TSR Hobbies in 1975. Megarry began working for TSR at the same time.

By 1976, Megarry had decided to leave TSR, but the publication of his game Dungeon! is cited as the first adventure board game.

Since then, the game has been re-released and re-implemented a number of times, including a WoTC edition in 2014. The edition used for this article is the Dungeon! - English Third Edition (1981) published by TSR, with art by James Holloway, Erol Otus, Harry Quinn, Jim Roslof, and Stephen Sullivan.3

Enter the dungeon

The goal of the game is to accumulate enough treasure (gold pieces, GP) and return to the starting room to win. It supports 2 to 8 players. The game board shows a dungeon divided into six, color-coded levels which thematically “lies beneath a large, haunted castle.”

Everyone starts at the first level and moves through the dungeon, including corridors, stairs, rooms, and chambers (large rooms). Areas are bounded by walls which have both doors and special secret doors. Rooms contain random monsters (61 monster cards) that must be defeated to take their treasure.

On a players turn they follow this sequence of play:

Move

Attack (or cast a spell) if there is a monster

Draw a monster card

Player attack (2d6 vs. target value)

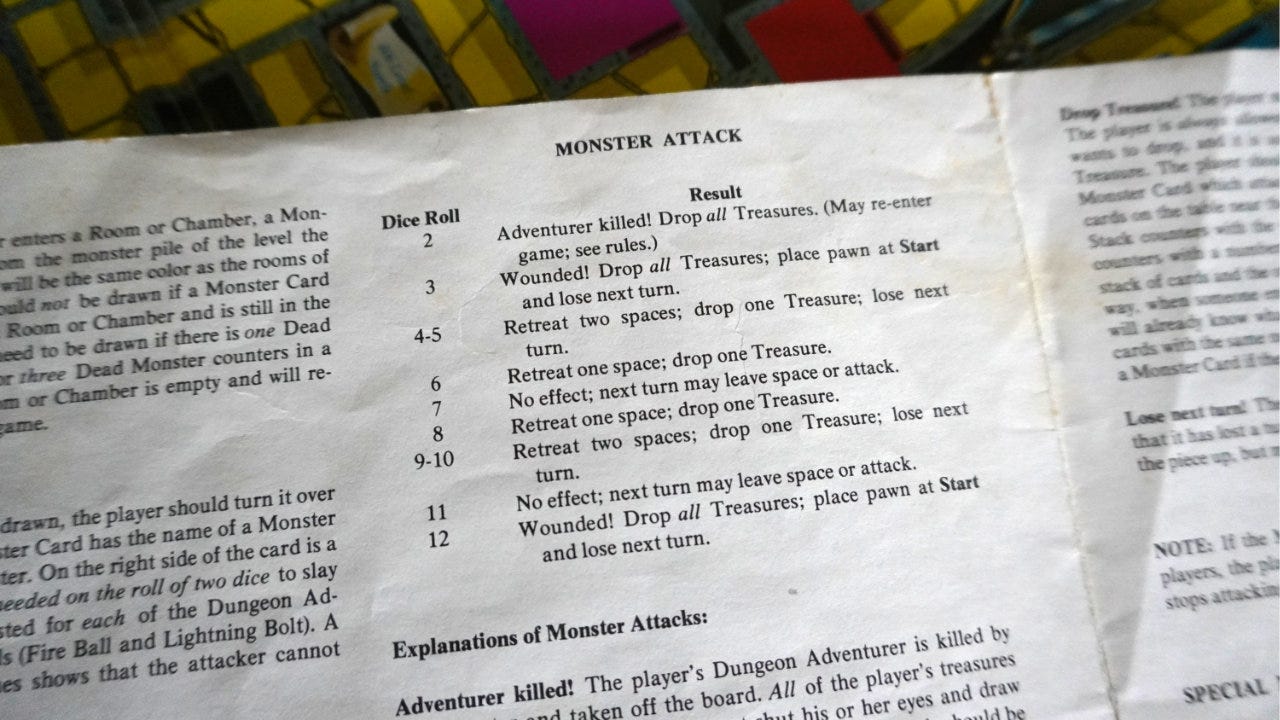

Monster attack (2d6 on results table)

Draw a treasure card if the monster was defeated

This cycle continues until one of the players has accumulated enough gold and escaped the dungeon to win.

Five interesting mechanisms

I firmly believe that you can learn something from every game you play, as I’ve noted before in Ten Lessons from Five Games. Dungeon! is no exception to this, in fact there are many things we can learn from its design.

Here are five mechanisms that stand out:

1. Asymmetric player powers

The first stand-out is that the game has asymmetric player powers. While rather common in modern board game designs (and in some older historical wargames), this would have been unusual in 1975-1981 for kids games.

Players choose a “dungeon adventurer type” at the start of the game and the matching colored pawn:

Elf (green, 10k GP): The weakest fighters and are recommended to stay in Levels 3 and below, as some high-level monsters may be unbeatable for them. They can use secret doors on a 1-4 roll on a d6 rather than a 1-2 like other characters.

Hero (blue, 10k GP): Better fighters than elves, they can also be successful in Level 4 dungeon rooms. No special abilities.

Superhero (red, 20k GP): Powerful fighters that can have success even in Level 5 and 6 dungeon rooms.

Wizard (white, 30k GP): Decent fighters, but with access to 1d6+6 single-use spells including Fire Ball, Lightning Bolt, and Teleport. Spells may be regained by returning to the starting room and waiting.

The game has point-based victory conditions (i.e. Gold Pieces), but the target is not the same for all players. The Elf, presumably the weakest character, only needs 10,000 GP to win while the Wizard, able to cast powerful spells, needs 30,000 GP to win.

This asymmetry creates a fun choice even before the game begins, and allows players to choose based on their style of play. The Elf might be poor at combat, but can easily slip through secret doors and move around the map much faster than others. The Superhero is great at combat, but needs twice as much gold as the Elf to win. The Wizard has an element of resource management in knowing when to use spells.

2. Modular map

The influence of GM-led games is evident in how the map is organized. There are six levels which give some indication as to how difficult the monsters will be within. The players never know, however, exactly what will be found behind the next door that they kick open.

In a GM-led game, the Game Master would decide what monster attacks next or what treasure is looted if successful. They might roll on random tables or have some pre-made ideas.

In Dungeon! the overall dungeon structure is fixed, but each room has an associated level color. When a player enters the room, a matching card is drawn that reveals a monster or a trap.4 With many paths through the dungeon, players have a lot of options for how to move to the next room, guaranteeing that no two games will play in exactly the same way.

This “kick the door open” randomness is at the core of games like Munchkin and Dark Fort. Dungeon’s use of grouped levels is an interesting addition that makes the game feel a little more thematic — easier monsters at Level 1 and harder ones at Level 6.

3. Single-roll, fast combat

Attrition-based combat can be a lot of fun, but it can also slow games down to a crawl. In Dungeons & Dragons a party might trade attacks and whittle away a monster’s HP over time, but it is the narrative and storytelling that keeps it interesting. Just rolling dice until someone drops dead isn’t as much fun.

Dungeon! handles this by using single-roll combat: roll 2d6 and either you win or you lose. This is made class-specific by difficulty tables included on each monster card showing the target value for each character type. A troll is immune to Lightning and killed by a Fire Ball on a roll of 7 or better. A Wizard and Superhero need an 8 to kill it, but the Hero needs a 10. Interestingly, the Elf only needs a 9 to slay a troll.

Magic swords can be found as treasure that will add a +1 or +2 modifier to the player’s attack rolls and are some of the best early-game items to find.

Wizards blindly cast spells into rooms before they know what they will find. Fire Ball (yes, two words) and Lightning are powerful and usually require a low target to kill, but sometimes (as in the case of the Lightning vs. Troll above) are completely ineffective. The ESP Medallion and Crystal Ball treasures help with this by allowing the player to reveal monsters before entering or attacking a room.

Undefeated monsters strike back and the results are based on an included table. The 2d6 roll is most likely to result in either “no effect” or retreating a space or two and dropping a treasure card. Dropped treasures are placed with the monster and add to the loot gained whenever the monster is eventually defeated.

This results in a combat system that usually has a single dice roll, and at most requires a second dice roll. It’s fast, easy, and uses the 2d6 probability curve in an elegant way.

4. Risk vs. reward

The division of rooms into levels combined with the ability to freely move between levels is a key feature of the game. This allows all players to independently decide how much risk they are willing to accept.

The Elf might be content to try to clear all the Level 1 rooms as quickly as possible, because they only need 10,000 GP to win. The number of Level 1 rooms is, however, finite so there might not be enough for everyone. They might instead try to hit some higher level rooms, knowing that while they might take some hits, one good payout might be a quick path to victory. A Level 4 Jade Idol treasure is worth 5,000 GP (50% of a victory), but a Level 4 Green Slime requires a roll of 12 on 2d6 to defeat it.

It’s this freedom of movement and difficulty that makes the game instantly feel thematic and captures the feel of exploring a dungeon. This is what I would consider a Layer 1: Core Gameplay thematic element. Even divorced from theme (or re-themed), the exploration and difficulty-selection mechanisms of Dungeon would still produce a similar feeling.

5. Solo play

Solo board games have seen a huge surge in interest in recent years, with most crowdfunded games advertising “Solo mode included!” as part of the marketing.5 This wasn’t always the case, so it’s notable that Dungeon! includes three methods to play the game solo:

Time limit: A real-time clock is set for 30 minutes and the player tries to win before time runs out. Set it for 25 to 15 minutes for more difficulty.

Specific treasure: Pick a specific treasure type and try to find it in the lower (i.e. harder) levels of the dungeon. Play against time or until two deaths.

Pursued by a monster: Choose a Level 6 monster card and place it face down next to the board. Every turn the monster (represented by a pawn) moves fives spaces closer to the player. If the monster catches the player, either it kills the player or is defeated. If defeated a new monster takes its place.

All three methods are viable options for playing solo. I particularly like the pursued by a monster variant, probably because it has a certain Eleventh Beast vibe to it.

More than a kids game

Dungeon! is a “kids game” that plays in an hour or less. It’s luck-based and shows its age when compared to modern board game designs.

That said, looking back on it almost half a century after the 1981 edition release, the game does some really interesting things. This is especially true when compared to other popular games for children from the period such as Trivial Pursuit, Scrabble, Sorry!, Battleship, and Monopoly.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Always something to learn: Every tabletop game, good or bad, can teach us things about game design. They can be sources of inspiration, provide mechanisms to use, or simply show us what not to do. The key is to have the right tools and vocabulary to be able to analyze how they work.

More than roll and move: It is easy to underestimate what kids can play and do. Dungeon! is designed for ages 8 to adult, and shows that kids games can have thematic depth and good decisions. The high amount of randomness (i.e. combat rolls) keep everything level and prevents skilled adults from running away with victory.

GM-less and solo games: Dungeon! started as a way to give David Megarry’s dungeon master a much needed break from running games. That design created something that was easy to convert into a solo game. This is probably true with most GM-less TTRPG game design — that they can be converted into solo games without much difficulty.

Have you played Dungeon!? If so, which edition did you play?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. You should follow Exeunt Press on Bluesky. 🦋

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

While writing this sentence I wondered if “exclamation mark” or “exclamation point” is correct. According to Wikipedia: “The exclamation mark ! (also known as exclamation point in American English) is a punctuation mark usually used after an interjection or exclamation to indicate strong feelings or to show emphasis.” So both are correct, but it is still tempting to just refer to it as U+0021 for the rest of this article.

For those of you who are always the GM, I appreciate your service and salute you.

The art in this game is great! It is simple yet memorable. Even treasures like the “Silver Necklace” which could have been just “throw-away” art, are colorful and evocative. I posted a few examples at Bluesky.

The two main types of traps are Cage and Slide. Cage causes the player to lose 1d6 turns, which is probably the worst mechanism in the game. Losing a turn is generally considered to be an outdated game mechanism, but losing six turns is just awful.

At last check, 84% of all solo modes were designed by Dávid Turczi. ;)

Omg my dad had this game and I messed with it as a kid without ever understanding what I had.

It's a shame that they never released the expansion that included the Superelf and Superwizard.