Fantasy Forest: a child's first fantasy adventure

Exploring player agency and meaningful decisions in TSR's Fantasy Forest

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

This is the second in a three-part series about classic TSR board games from the 1980s. Don’t miss Part 1 - Dungeon! and Part 3 - D&D Computer Labyrinth Game.

Last week we looked at TSR’s Dungeon! from 1981 and explored how David Megarry captured some of the spirit of his Blackmoor games with Dave Arneson in the game’s design.

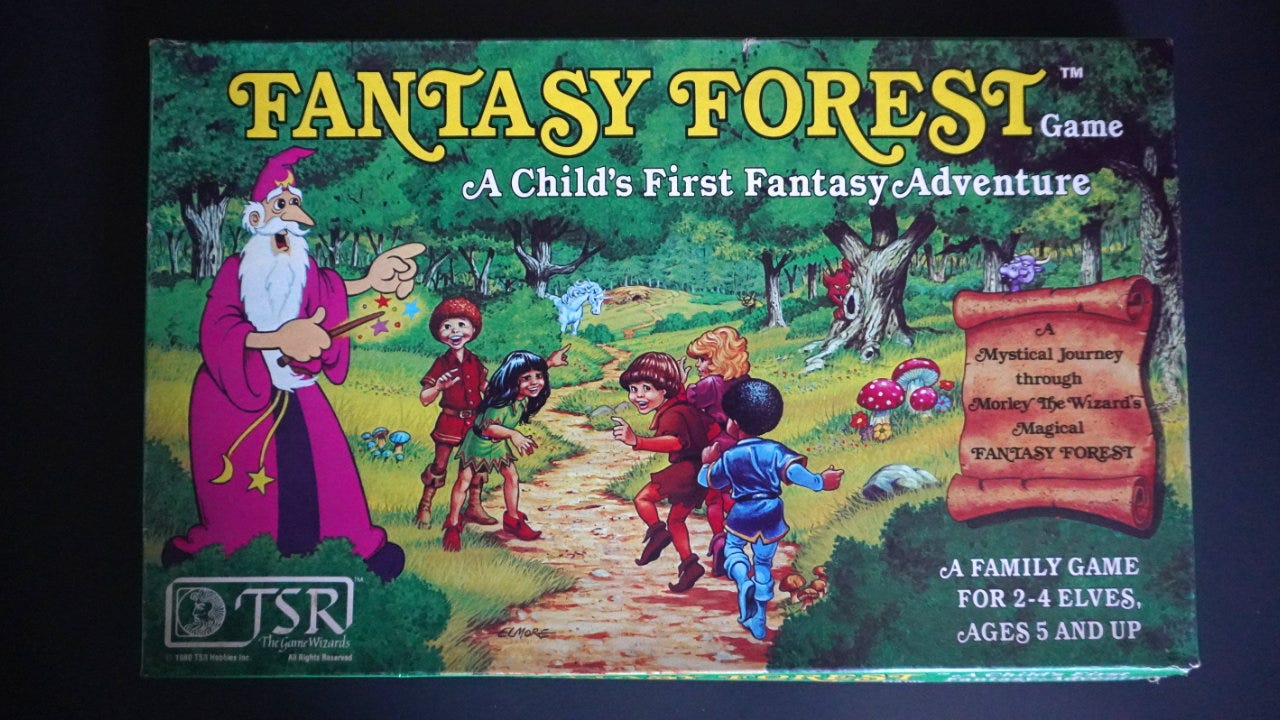

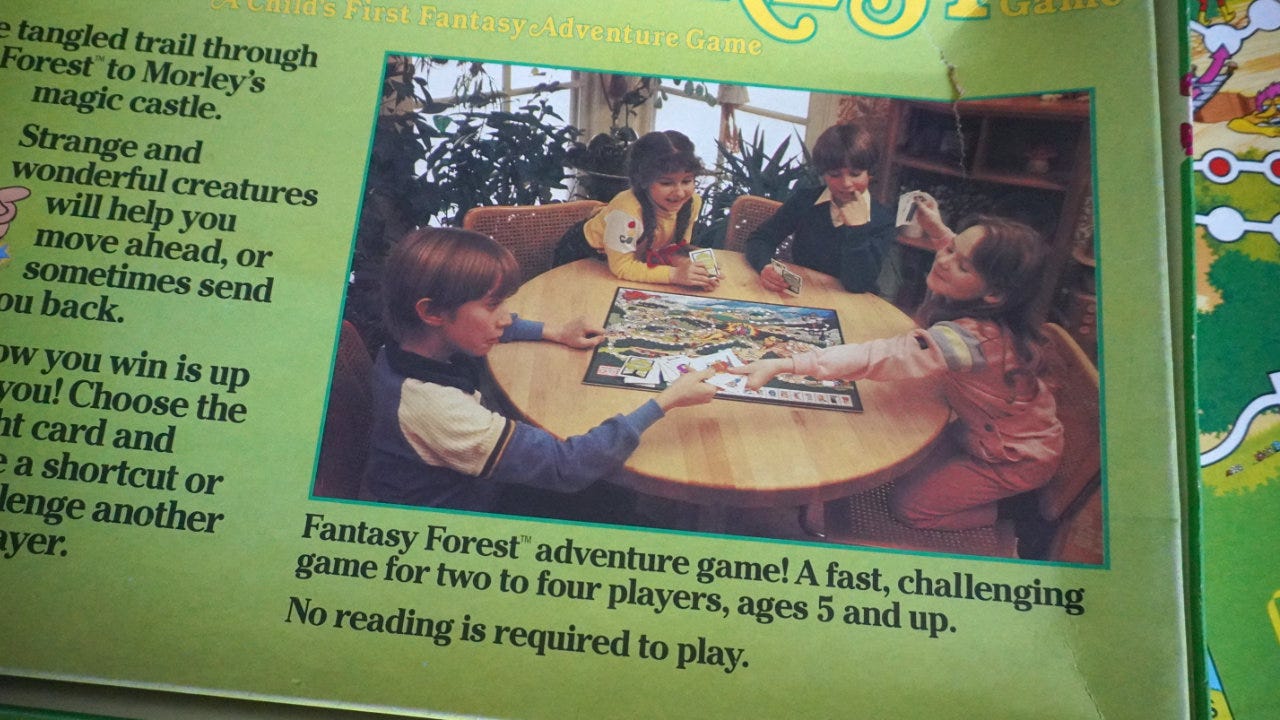

This week we continue looking at classic TSR board games with Fantasy Forest, a kids game from 1982.1 The art is by Larry Elmore, one of the most famous TTRPG artists and who created the iconic Basic D&D Ancient Red art.2

Fantasy Forest might be designed for ages 5 and up, but there are a few lessons we can learn from this game.

Fantasy Forest

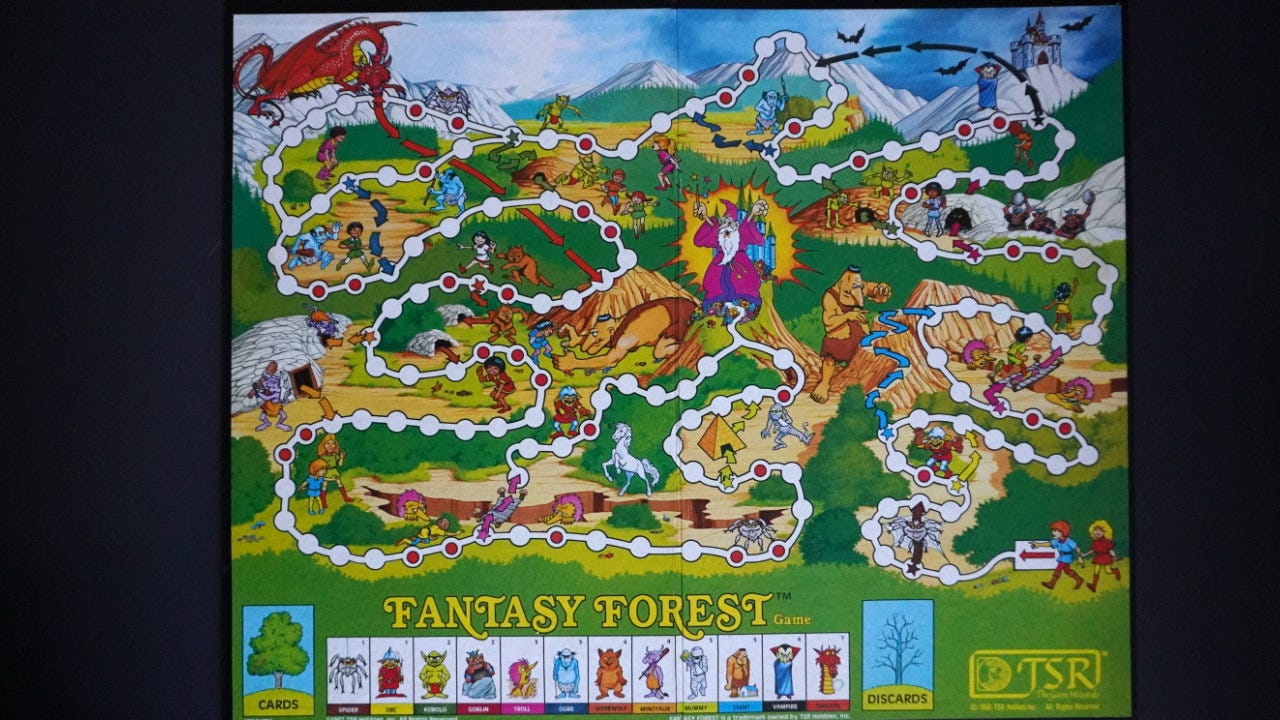

The comparisons with Candy Land (Abbott, 1949) are obvious. In Fantasy Forest (Gray, 1982) players use pawns on a board to race on a track to a goal space on the board. Cards are used to determine how far each player moves on their turn. In both games, the rules can fit inside the box lid.

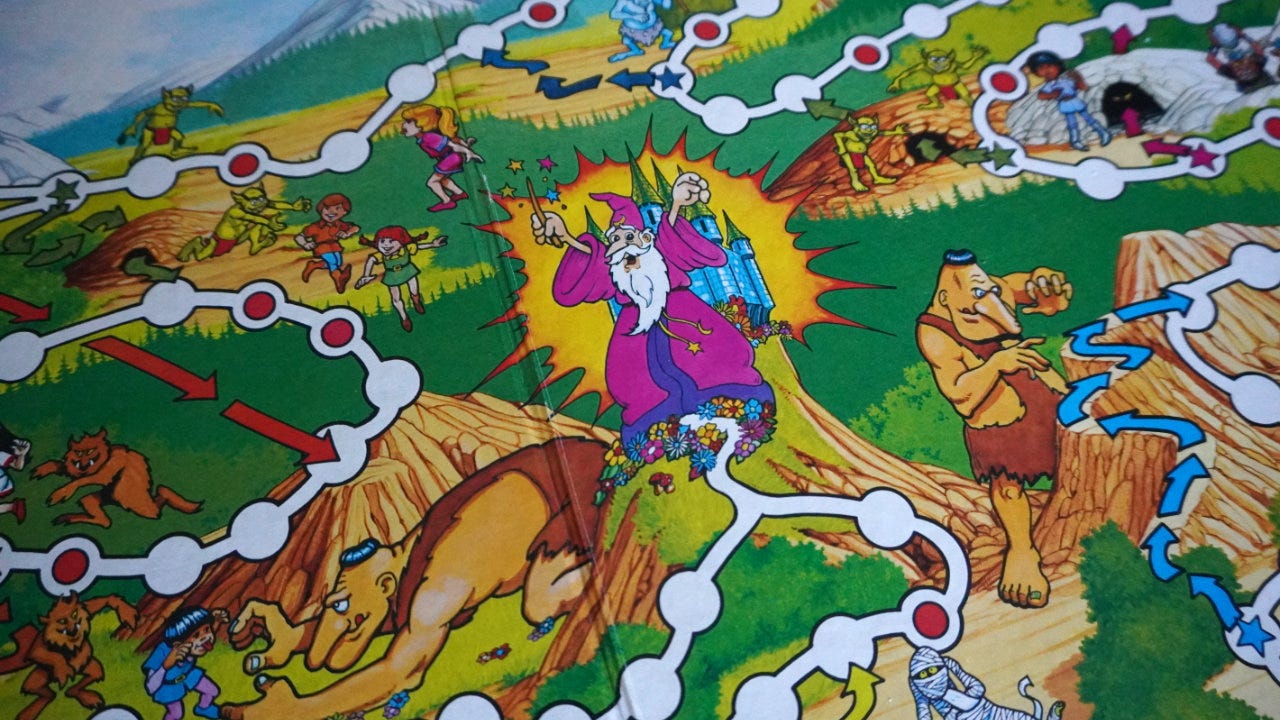

Fantasy Forest does, however, make a few simple but significant changes. Most importantly, the deck is made of cards with both numbers and monster art on them. Each monster card has a value and a color. Spiders and Orcs are 1, Kobolds and Goblins are 2, all the way up to a Vampire (6) and Dragon (7).

On a player’s turn they draw a card and then either:

Play a card to move ahead: Move ahead the number of spaces equal to the value of the card.

Challenge another player: Each player draws a card and they are simultaneously revealed. If the challenger wins they move to the space ahead of the other player. If they lose, they stay where they are.

After moving, if they end their turn on a “clear” space (i.e. one without a red dot), their turn ends. If the space does contain a red dot, there is an Ambush. The player reveals one of their cards and compares it to the top card from the draw pile. If their card is the same or higher, they win and move additional spaces equal to the card played. If they lose, they move back spaces equal to the other card.

There are also Shortcuts that can be accessed by playing a card matching the color of the shortcut. For example, a Giant (blue) card can be played to take the blue shortcut as indicated by the blue star and arrow.

If you land on a space with another player, you can take their cards, choose the three you want to keep, and give them the other ones.

Play continues until someone reaches Morley’s Castle. First one to reach it is the winner.

Player agency and decisions

Player agency is the ability of players to interact with the game world in a meaningful way:

The power to influence the game state

The ability to control what happens next

The need to make meaningful decisions

We looked at this before using the FADC and CCI models for player agency and how they can be applied to TTRPGs such as ones based on the Carta SRD.

When I taught the tabletop game design class and discussed player agency, I used Candy Land as an example of a game without player agency.3 In the game, players draw a card and move to the next space of that color. There is no decision to be made. There is no ability to influence which card is drawn or where the player will land. It is an example of pure randomness.

In the class we looked at ways to increase the amount of player agency in Candy Land, such as drawing two cards and playing one or having multiple paths to choose from. It’s a fun exercise, and helps focus the design on the player’s experience.

What struck me about Fantasy Forest is that it is essentially Candy Land, but with the player agency ramped way up!

Dragons, trolls, and meaningful choices

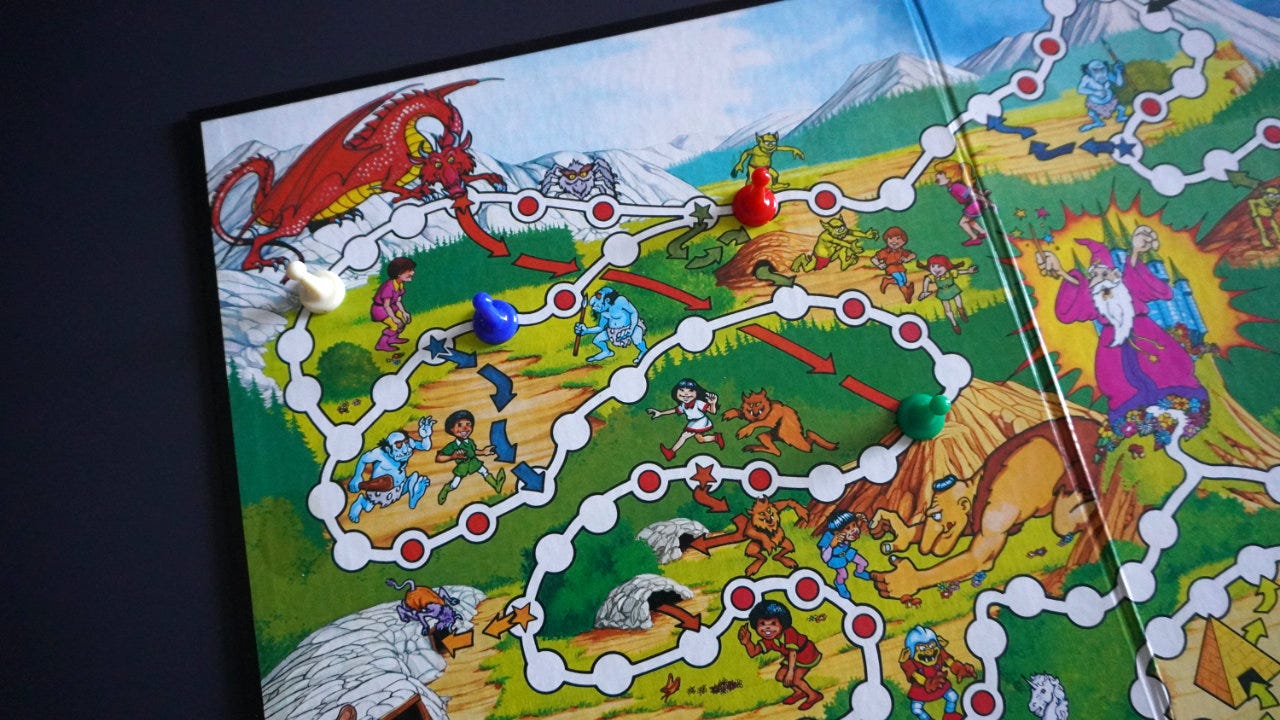

The most obvious way that Fantasy Forest increases player agency is that every player always has three cards in their hand. If they ever discard one (e.g. playing a card to move or challenge a player), they always draw back up to three cards. This ensures that players always have a choice in which card they play next.

Having three cards turns into hand management when combined with the other mechanisms:

Multiple paths and shortcuts: Multiple shortcut paths exist on the map which can be unlocked with a matching card. There’s also a fork in the road at the dragon’s mountain. A player may want to retain a card matching the shortcut, but also want to play it to move ahead.

Monster ambushes: Landing on a red dot can be a significant advantage if you are able to defeat the monster with a higher value card. Winning allows you to move ahead a second time, but losing moves you back. Holding onto a high value card (e.g. Vampire 6 or Dragon 7) allows you to win ambushes, but at the cost of not playing them to move.

Player challenges: Players can challenge others and attempt to move one spot ahead of them, regardless of where they started. This is a catch-up mechanism, a feature that helps players who are falling behind in the game close the gap with the player in the lead.4 If a player has only low value cards in their hand, they are vulnerable to player challenges.

It is the competing desires and choices available that creates an engaging player experience. This is particularly the case when the available choices are all positive, meaning it is the feeling of “I want to do all of the above!” rather than “I have to pick the least bad option.”

Fantasy Forest manages to create an experience where players want to keep high value cards in their hand, save them for shortcuts and challenges, and also play them to move on the board. Those options can’t all be done at the same time, and creates the necessary tension for a satisfying player experience.

The dragon’s mountain

Let’s look at a specific example of how Fantasy Forest uses meaningful decisions in the game.

At the top left portion of the board there is a dragon on a mountain. There are two connected paths that traverse that area. One path is longer (9 spaces) and one is shorter (6 spaces), and there are three available shortcuts (green, red, dark blue).

The player has a couple options:

Good: Take the shorter path with a chance for the Ogre (3, blue) shortcut.

Better: Try to get a low-value Kobold (2, green) card lined up so they can take the shortcut and skip the mountain area.

Best: Take the longer path and hope to have a Dragon (7, red) which unlocks a valuable shortcut, skipping 18 spaces ahead.

Note that the best path is the dragon shortcut, but missing it leads to a longer path. The other shortcuts require less valuable cards, but they also don’t skip as many spaces.

Without a doubt, Fantasy Forest is still a luck-based kids game, but one that has luck mitigation mechanisms to create a player experience where decisions matter.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Good, bad, doesn’t matter: Fantasy Forest has an average rating of 6.7 on BGG, which actually isn’t too bad for a retro kids game. I’m sure nostalgia is boosting that score a little bit, but it doesn’t really matter. It is valuable to analyze and think about all games, and see what we can learn from them.

Increase player agency: While not always true, in most cases increasing player agency is a good way to create a more engaging player experience. When designing Caveat Emptor, I took time during the process to map out each decision point and to consider how to make each choice meaningful.

Use a player agency model: I’ve found the CCI model to be extremely helpful when thinking about games. As an exercise, choose a simple game that you enjoy and try to map the decision points and choices on paper. For each one, check to see if it meets the Choice, Control, and Influence criteria.

Have you played Fantasy Forest? If so, did you play the original 1982 edition or the 1990 re-release with the Dungeons & Dragons cartoon figures?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. If you want to see more art from Fantasy Forest, follow Exeunt Press on Bluesky!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

There was a re-release of Fantasy Forest in 1990 with “play figures” that appear to match the Dungeons & Dragons cartoon. It changed the rules by adding “hero cards” which allowed players to use the figures to access alternate paths on the board. BGG has a few photos, including one of the figures.

I found a Previews World interview that quotes Larry Elmore as saying, “Right off the bat, they put me to work, and I did a bunch of different covers. They were also putting out a little board game for kids, which I also worked on – that was called Fantasy Forest.”

The lack of player agency is not related to whether Candy Land is “good” or “bad.” It’s a great game to teach children the concepts of taking turns, using cards, and moving pieces on a board. Games without mechanical player agency can be really fun. In fact, I even made one. You can read more about that in the The Carta SRD and player agency post.

Catch-up mechanisms are included in many modern board games with the goal of preventing anyone from being completely knocked out of a chance to win the game. Games without catch-up mechanisms can be susceptible to what’s called a “runaway leader” problem where winners win more and losers lose more.