Help libraries add your game to their collection

Exploring the world of library catalog and bibliographic data, and why it is important for indie creators to understand the basics. Let's talk about ISBNs, MARC records, and CIP blocks!

Libraries are great. As a patron, I just stop by my local public library, request a book via inter-library loan, and it shows up the next day. The process is completely transparent, but behind the scenes it’s pretty amazing that it all works!

This week I want to share what I’ve learned about what it takes to get your game (e.g. TTRPG zine) into your library’s collection.

Or at least, how to make it a little easier for the librarians working there!

Exeunt Press is a gold sponsor of the 2025 ALA International Gaming Month!

I am not a librarian

While I do support public libraries (and think you should too) and I am an ALA member, I am not a librarian. None of the following is legal advice. You should talk to experts before making business decisions. But I want to share what I’ve learned so far, and this article is my attempt to do that.1

Why do we care about metadata?

Cataloging books (and other items) as they enter a library’s collection is a deceptively complicated task. And yet, if you’d like one of your publications to be part of that collection that’s the work that must be done.

After talking to Rebecca Strang via the ALA Gaming Round Table, I’ve learned that even when librarians want to include more games, it’s not easy to do so.

For example, indie TTRPGs (particularly solo games) are increasingly popular. Yet they are often published by individuals with limited means vs. a large publishing company. The game may or may not have an ISBN. Perhaps it’s a pamphlet, PDF, or a staple-bound zine. Some require dice and components and others are made to be written in. Can it be stored on a shelf or require a plastic box as a kit?

If you are an indie game designer who wants to get your games in libraries, it makes sense to make it easier for librarians to add your items to their collections. This means providing as much catalog data as possible in the right formats.

How do we do that? Well, first we need to understand some of the most common types of catalog data.

Types of bibliographic cataloging data

This is not an exhaustive list of cataloging data types and formats, but it is probably a good list of the ones you should understand. Some I was familiar with simply from being a consumer (e.g. ISBN), but other more esoteric formats (MARC21) are known only to those who understand the deep magic of library science.

Consider this your crash course in library cataloging:

International Standard Book Number (ISBN)

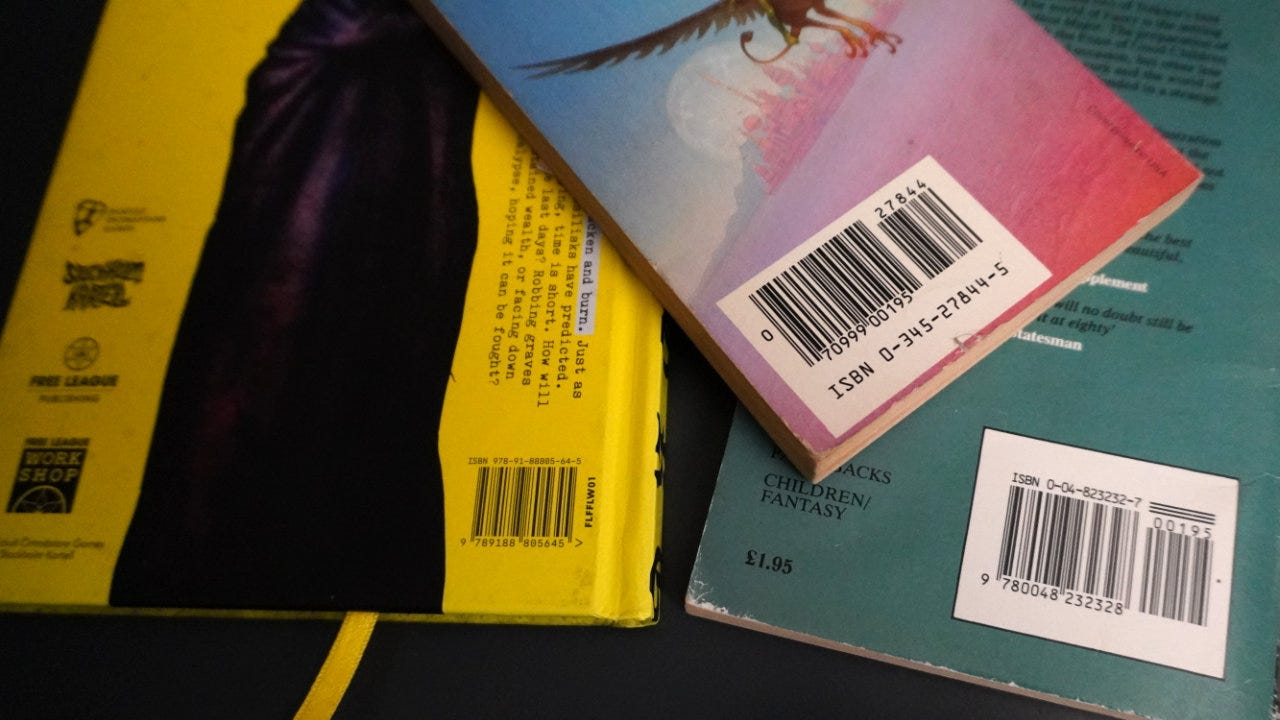

An ISBN is a unique identifier for a commercial book consisting of a 13-digit code.2 The system has a long history beginning in 1965 and eventually adopted as an ISO standard in the 1970s. Today’s 13-digit code has been in use since 2007.

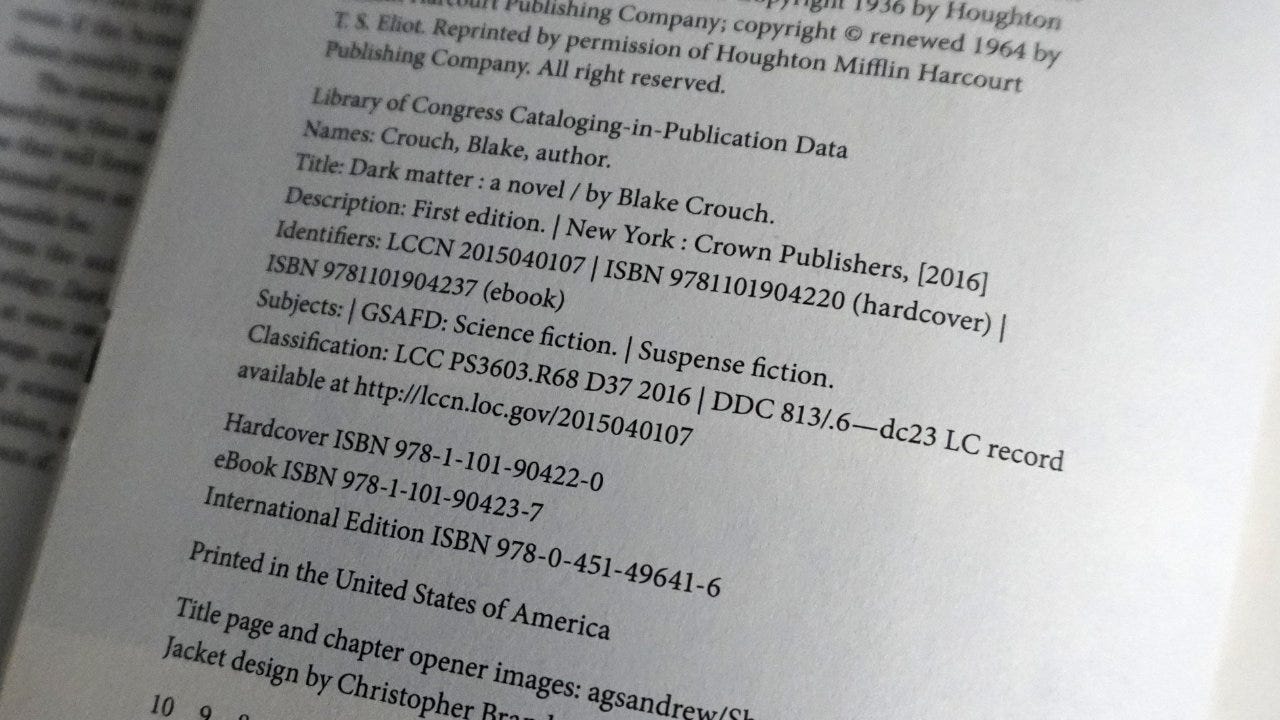

Each edition or unique variation of a publication (e.g. paperback, hardcover, epub) gets its own ISBN. Therefore a single book might have multiple ISBNs associated with it depending on the format. Periodicals that are routinely published as issues (e.g. magazines or newspapers) typically use an International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) instead of an ISBN.

The International ISBN Agency manages the overall pool of unique identifiers and issues blocks of them to specific countries. You don’t, however, get your ISBN direct from the International ISBN Agency. Instead you go through a registration agency in your country — how that works depends on your country.

In the United States, ISBNs are managed by R.R. Bowker LLC (“Bowker”) based in New Jersey.3 If you want to get an ISBN for your publication, you’ll need to go through them via the Bowker Publishing Services site (www.myidentifiers.com). You don’t need to be a publisher or have special access to do this.

As of September 2025, the pricing encourages bulk purchases:

1 ISBN for $125 ($125/identifier)

10 ISBNs for $295 ($29.50/identifier)

100 ISBNs for $575 ($5.75/identifier)

1,000 ISBNs for $1,500 ($1.50/identifier)

After you purchase a block of ISBNs, you can log into the website and assign the numbers yourself. This includes entering catalog information such as title, author, format, categories, and so on. This information is not encoded in the ISBN and exists only in Bowker’s database.

Bowker also offers barcode generation services for $25 each, but there are free generators online that can do the same thing.4 If you don’t mind not having your barcodes stored in the Bowker identifier database, you can save some money by making your own.

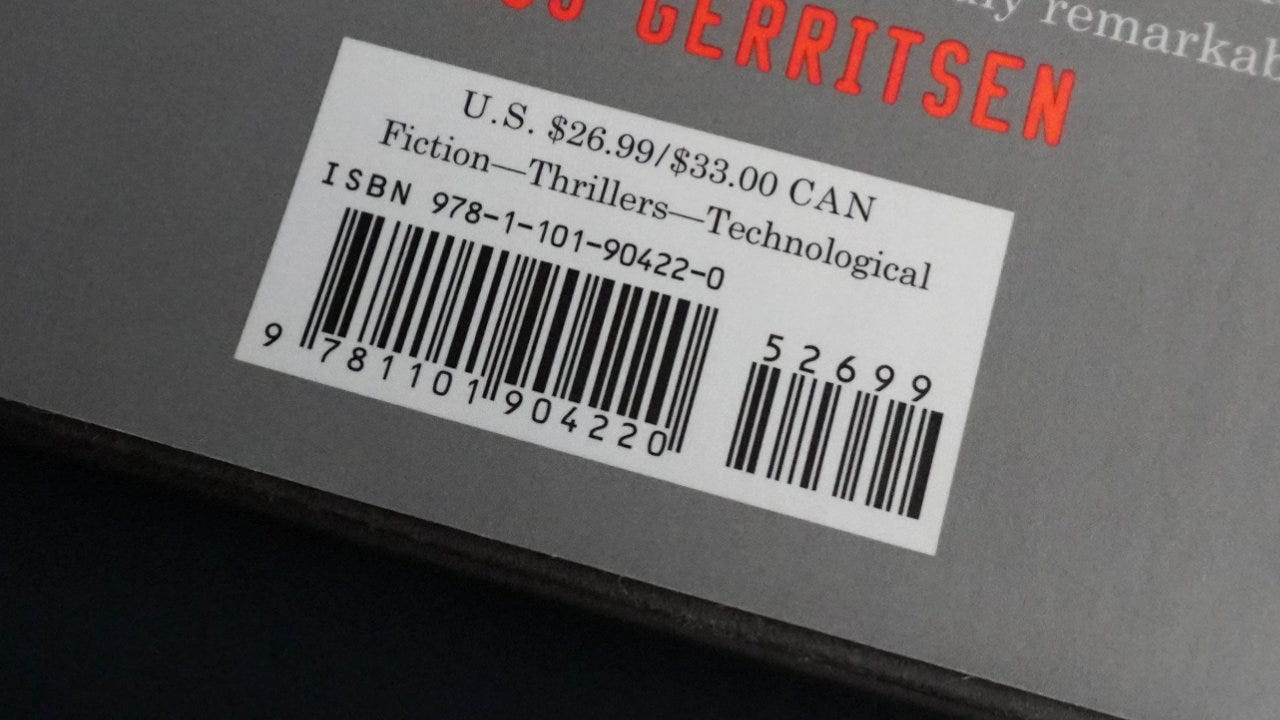

Some bookshops require an ISBN and EAN-13 barcode to stock your items. An additional 5-digit EAN-5 barcode may be included as well which encodes the suggested retail price of the book and currency (e.g. 5 = USD, 6 = CAD). If you don’t want to include the price in your barcode you can list the EAN-5 value as 90000 which means no price is given.

Note that while an ISBN is a unique identifier for your book it does not contain any useful bibliographic or catalog metadata — no author, title, format, or anything else.

Machine-Readable Cataloging (MARC) Records

Computer analyst Henriette Avram developed the MARC format while working at the Library of Congress in the 1960s with the goal of making it easier to share electronic records between libraries. MARC records quickly became an international standard and are still the primary format used by libraries.

MARC records are electronic records that contain bibliographic catalog data for items in a library’s collection. They are structured so that online catalogs can share, import, copy, and display records consistently across libraries. In general, libraries need MARC records for each item to be able to add them to their catalog.

While there are many specific versions of MARC used in different countries, MARC 21 (1999) is the most popular.

Unlike ISBNs, you could potentially create your own MARC records for your publications. There is, of course, a Python module for working with records (Pymarc).5 Just take one look at the MARC 21 data format (summary), however, and you’ll probably want to outsource this task.

Third-party services exist that will create the MARC records for you. The cost is roughly $40-$45/record for print books, but the actual price depends on the format of the materials and the availability of already-created records. MARC records for specialized formats (e.g. board games in a box) might cost $75 or more. Records for items that are in languages other than English might also cost more if using a US-based service.

After the record is created, it will need to be made available to libraries. There are a few ways to do this:

Publish on your own site: Publish the MARC record on your own website and direct the library to where they can download it.

Publish on someone else’s site: Include the MARC record with the PDF version on a distribution site such as itch.io or DTRPG.

Use an online catalog service: Have a third-party service publish the MARC record to an online bibliographic data source such as OCLC WorldCat or SkyRiver. Libraries can then find your record in the online database and copy it to their local catalog.6

The MARC format, approaching 60 years old, is showing it’s age.7 But for now, it’s the most common catalog data format.

Cataloging-in-Publication (CIP) Block

Usually pronounced as “sip block”, the CIP block system was established by the Library of Congress in 1971. The block is developed prior to publication of the title so that it can be included in the book itself (i.e. printed inside). The standard placement is opposite the book’s title page. The data is an abbreviated version of the MARC record, including name, title, description, identifiers, subjects, and classification.

While CIP blocks can be officially prepared by the national library where the work is published (e.g. Library of Congress in the US), unless you are a major publisher your application will probably not be accepted.

Instead, small publishers will need to rely on third-party services to prepare CIP blocks that conform to the standard. The cost is more than a MARC record and may be between $100 - $150 per block.

Unlike MARC records that can be created after publication, CIP blocks need to be prepared prior to publication so they can go into the book. Also, if you make changes to the book (e.g. rewording a title or changing an author’s name format) after the CIP has been prepared, you’ll need to ask for revisions.

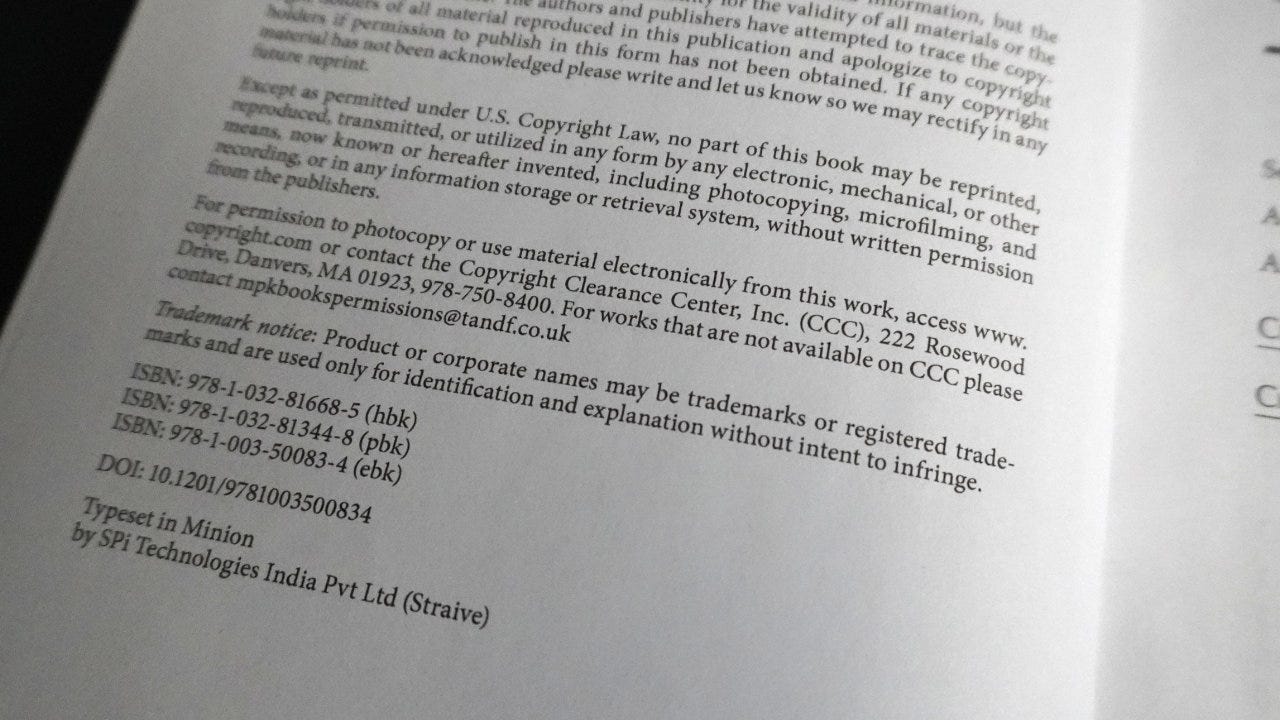

Digital Object Identifier (DOI)

Where ISBNs are simply unique identifiers, a DOI attempts to be a persistent identifier that work like a URI. Where a URL (a subset of URIs) identify the location of a resource, a DOI identifies the resource itself.

It’s all quite complicated and mostly used in academic settings, journal articles, and ebooks. In general, you won’t need to worry about DOIs to get your publication in your local library, but I thought it was worth mentioning.

Just tell me what I need to do.

So you made a game — a solo journaling game that consists of a single book or zine. You want to make it easier for libraries to add it to their collections.

Here’s what you should do:

ISBN: Buy some ISBNs and assign one of them to the game.8 Enter the information in the Bowker website and generate a barcode. Print the ISBN inside and put the barcode on the back. Make sure it is large enough to be readable. Approximate cost: $5.75

MARC record: If you want to make it really easy for librarians, create a MARC record for your game. Have them upload it to OCLC so it’s available to most libraries. As a backup method, include the MARC record wherever you provide the game (your website, itch.io, DTRPG). Approximate cost: $45

CIP block (optional): Less necessary than the MARC record, but not a bad idea. Use a third-party service to generate the CIP block and then include it inside the front of the zine printed exactly as provided. This can be useful for libraries that don’t have OCLC subscriptions. Approximate cost: $145

Generating and providing this information isn’t free. Using the rough estimates above (September 2025), the total cost per title would be about $190 USD. If you skip the CIP block, it’s about $50 per title.9

But providing this information makes it easier for libraries to add your game. It improves visibility in catalogs after it’s added and increases the chances that a potential player finds your game.

Third-party cataloging services

Rebecca Strang (ALA GameRT) recently arranged a call with Cassidy Cataloguing Services and a few indie creators to learn more about the process. I was able to join (along with Almost Bedtime Theater) and speak with Megan Staloff, Natalie White, and Tani Eckstrand from Cassidy. That’s how I learned the basics of what it takes to get a book into a library catalog.

Based on the discussion, the Cassidy team looks forward to working with small creators to develop catalog information (MARC records and CIP blocks) for their works: “Think of us as translators who help your game/book speak fluent ‘library,’ making sure your materials find their way onto shelves everywhere.”

I plan to follow up with them to get specific pricing to generate records for Exeunt Press games.10

Their contact email is info@cassidycat.com.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Libraries are awesome: If you are an indie creator, there are ways you can support your local public library beyond simply giving money. You can teach a game design class for free. Or you can sponsor International Games Month by donating copies of your games.

Lower the barrier to getting into the catalog: It’s a lot more work to get a book properly added to a collection than you’d imagine. You can’t do all the work, but you can make the job a little easier by providing accurate catalog data in the right formats. Having an ISBN and MARC record makes it easier.

It’s going to cost some money: Whether it’s buying an ISBN or generating MARC records, there are some costs involved with this. It’s not free. That said, depending on if you go with a CIP block or not, the cost could be in the tens of dollars per title.

What do you think? Would you consider providing library catalog data with your games? If so, would you include a CIP block or not?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

To paraphrase Douglas Adams, though this article “has many omissions and contains much that is apocryphal, or at least wildly inaccurate,” it is free.

The digits encode information including a GS1 prefix, registration group, registrant, publication element, and a check digit. The parts are sometimes separated by hyphens but don’t need to be.

According to René-Pier Deshaies of Fari RPGs on Bluesky: “Fun fact for Canadian TTRPG creators: you don't need to pay $100 to get an ISBN like folks in the US. Library and Archives Canada allows you to get free ISBNs for your projects. Takes around 4-6 weeks for your account to be created but then you are good to go.”

I typically use the ISBN barcode generator from Kindlepreneur. Seems to work fine and will output as JPG, PNG, or PDF. If you don’t want to include a price, just enter 90000.

Pymarc acknowledges that “most often you will have some MARC data and will want to extract data from it.” Using it that way seems like it might have some fun applications.

Note that the library (or library system) needs to be a member to access these services. Large libraries almost certainly are members and would prefer this MARC record distribution method. Small, rural libraries may not have access and would need to rely on other distribution methods.

For example, the records are transmitted via binary files, sometimes with multiple records stuck in the same file. A more modern approach might use XML or JSON. The Library of Congress launched BIBFRAME in 2012 to try to create a new data model for bibliographic description data, but with millions (billions?) of existing records it’s no small task. Yet some claim MARC MUST DIE.

While libraries don’t really require ISBNs, I think it’s a good practice if you ever want to sell or widely distribute your game. At some point, someone will want that ISBN and it’s easier to deal with that sooner than later.

A low/no cost alternative to the MARC record would be to make a metadata one-sheet for your game. Include as much information as you can in a clear, readable format: title, author, publication date, ISBN, physical details, subjects, keywords, and short summary. The library will still need to manually create a MARC record for you, but it’s better than nothing.

IMPORTANT: I have not yet used Cassidy for any services and this article is not an endorsement. For full disclosure, they did review this article for technical accuracy before publication. They also provided the quote and pricing figures used.

just wanted to echo how awesome libraries are :D what a great resource. as a life-long lover of libraries, and the daughter of a librarian, i really appreciate you putting this out there :)

I know I've said this in other places, but I also wanted to say it here! Thank you so much for everything you do to promote games in libraries! It's been fun having these conversations and it means a lot that you continue to seek out and SHARE the information. Libraries aren't one-size-fits-all in their processes, nor are game designers, and that can make it tricky to get games on shelves sometimes, but there are ways forward and interested folks to help along the way. Thank you for being a helper!