Solving an emergent murder mystery

Exploring emergent narratives with The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Previously we looked at Grasping Nettles by Adam Bell, and how it used a rondel and action selection to create a really interesting worldbuilding game.

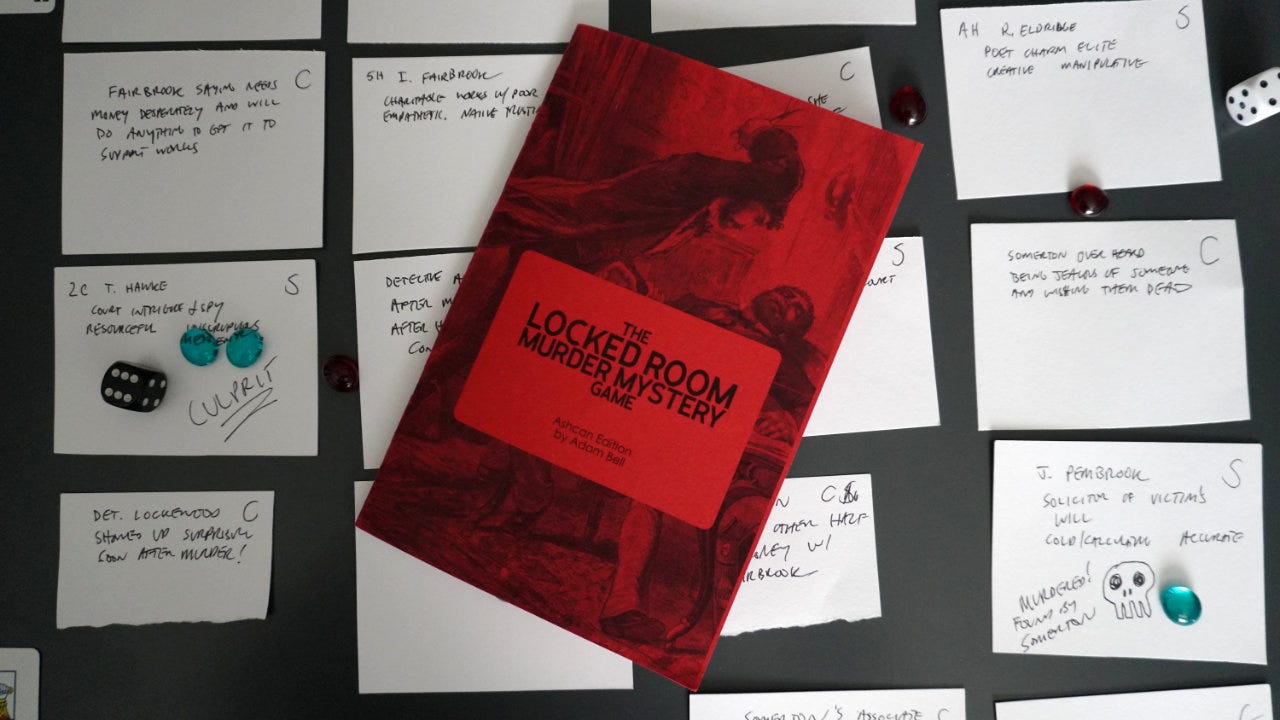

This week I had a chance to play the other Adam Bell game that I picked up last year: The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game. Specifically, it is the PAX Unplugged 2023 Ashcan Edition, and is therefore a work in progress.1

It’s an excellent example of how a game can use emergent narrative to build a coherent mystery to solve where none of the players know how it ends!

Want to try making your own TTRPG? The Make Your Own One-Page Roleplaying Game guide from Skeleton Code Machine will help you get started!

Emergent narrative

In game design, emergent narrative usually means that the game lacks a pre-planned, defined, script. Instead, the story or narrative of the game is organically created by the player(s) of the game via the act of playing it. It is the interaction of the player with the mechanisms of the game and with other players that creates meaning.

Board games that do not have an explicit story can still have a narrative arc that arises during gameplay. Examples include Betrayal at House on the Hill (2004), The King’s Dilemma (2019), Pax Renaissance: Second Edition (2021), Obsession (2018), and John Company: Second Edition (2022).

TTRPGs are, by their very nature, excellent at producing an emergent narrative. Player-driven choices, dice rolls, GM planning and decisions, all come together to produce a story that no one at the table knew before the game began. Certainly the GM would have a general idea of the story they wanted to tell, but rarely does that plan survive the first few dice rolls!

The mixture of player agency, randomness, and lack of strict goals are all critical to building the narrative.

The challenge of murder mysteries

Emergent narrative works well in games where the story doesn’t need to end up at a single, specific conclusion. You can run a Mothership RPG campaign and just see where it ends up. It doesn’t matter which player wins or who tanks the company in John Company: Second Edition. Regardless of which guests you entertain in Obsession, the game will come to an end.

In a murder mystery game, however, the design challenge is significantly tougher. The genre demands a coherent story that begins with the mystery and ends with a solution. Someone is murdered, clues are collected, and the culprit is apprehended.

This can be extremely hard to do when characters, plot, and other devices are all randomly generated. How can you find a clue leading to the murderer when the murderer hasn’t been defined yet?

The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game

The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game tackles this hard design problem head-on:

The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game is a tabletop storytelling game for one or more players inspired by Golden Age murder mystery detective novels. Create a cast of characters gathered in one place. Fill their lives with tension and secrets. Join our great detective as they solve the mysterious murder of one of our characters found in a locked room. Play out the investigation until the true culprit is determined, and reveal the truth hidden among the clues and suspects in the detective’s journal.

It’s a GM-less game that can be played solo or with multiple players:

As you play, you'll come up with the characters and details and how they interact, and the game mechanics will determine who dies and who is culpable when the time is right.

The game is conducted in a number of phases:

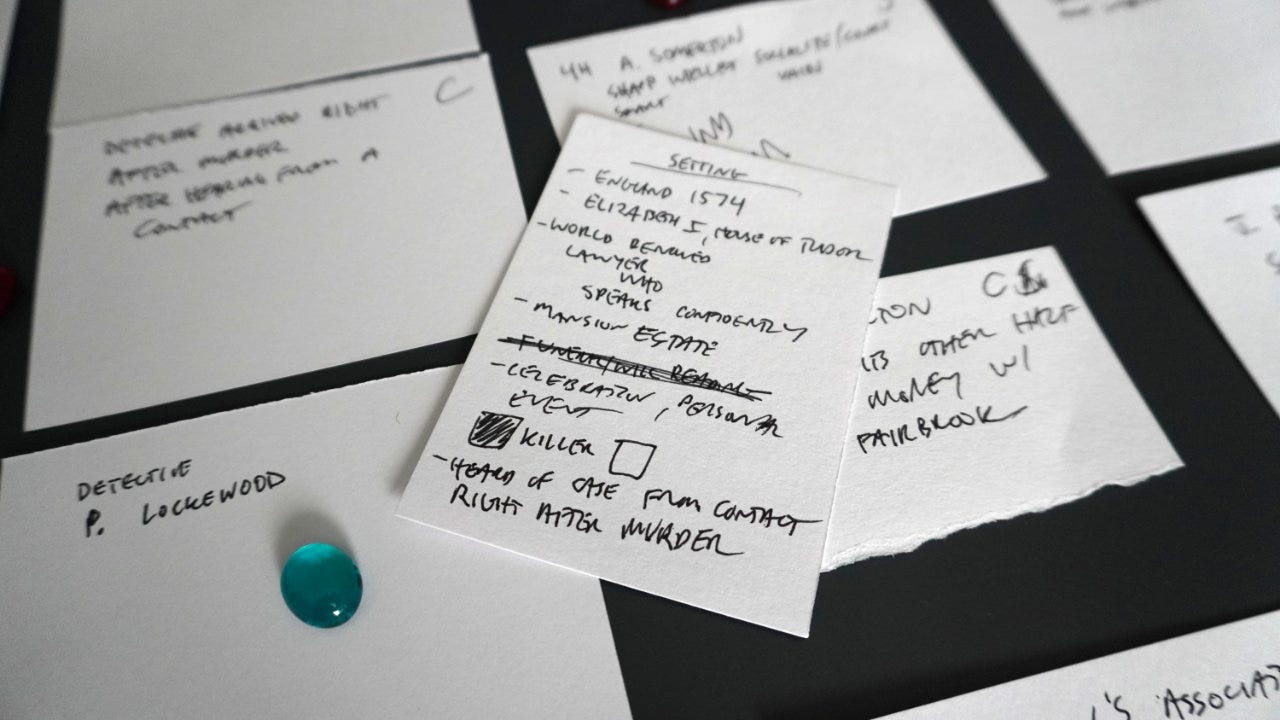

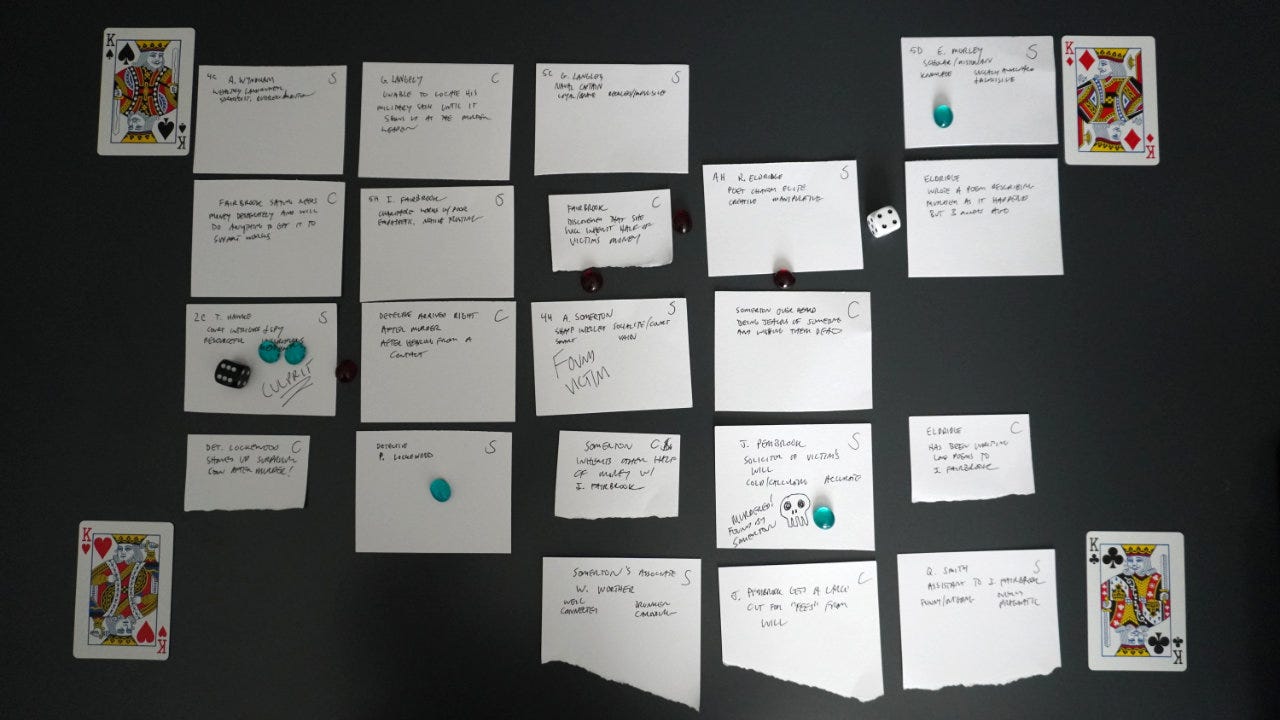

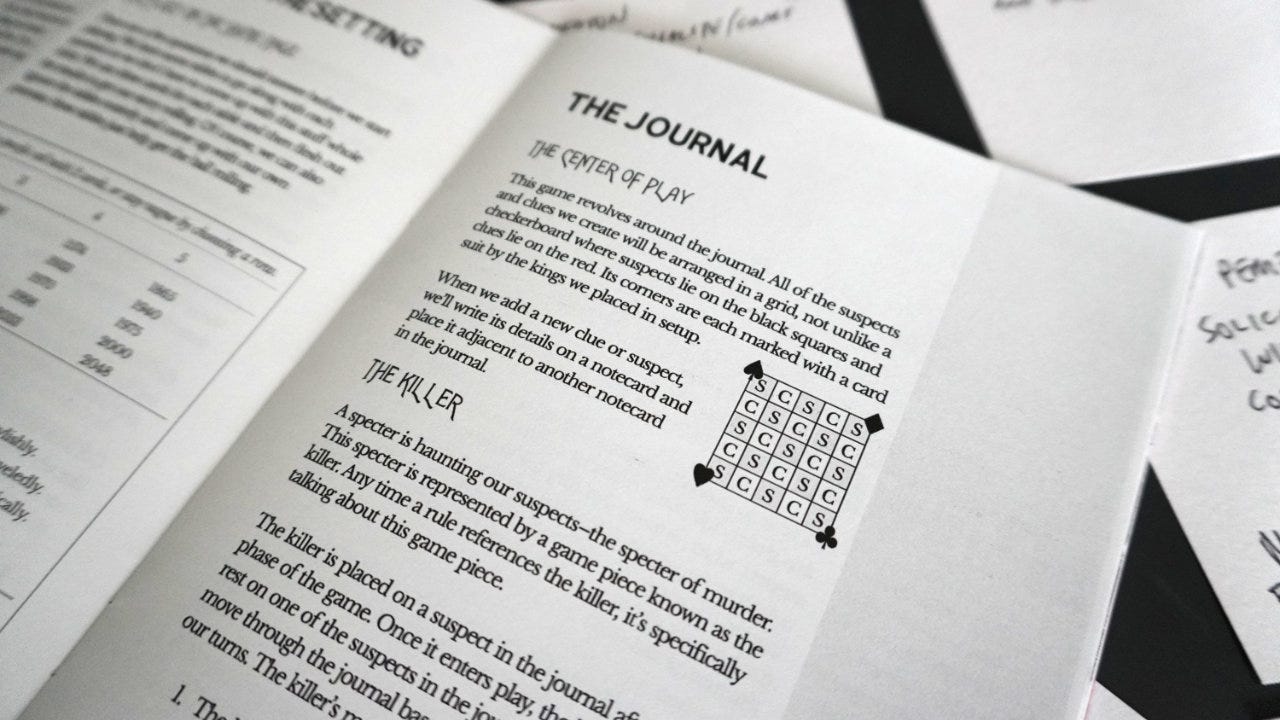

Meet the Suspects: Using a 5x5 grid called the Journal, players take turns creating new Suspect notecards, each with a name and description. The playing cards are used to determine when the Detective arrives and what the cause of death was (e.g. gun, knife, blunt object, etc.), and then the story begins.

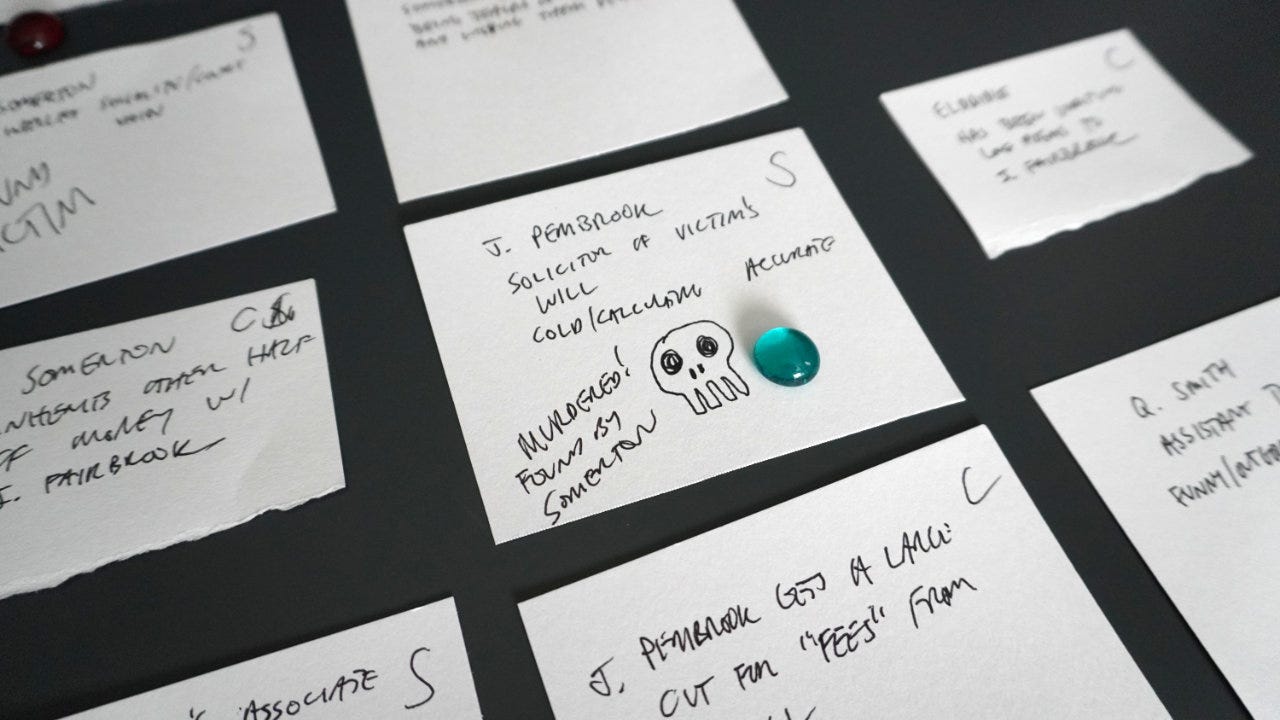

The Story Begins: The Killer, represented by a token, moves diagonally around the Journal notecards “like a Bishop from chess crossed with the screensaver from a DVD player.” Clue notecards are added based on the Killer’s location, and placed adjacent to Suspect notecards. At the end of this phase, the Killer murders the current Suspect (and possibly others), and additional crime scene clues are added based on the cards.

The Investigation: A Sleuth token moves between the cards turning questions (i.e. the adjacent clue and suspect) into answers. Some answers lead to the “rot” at the heart of the case, and others solve the murder itself.

Summation: The Suspect that the Killer’s token is on is the Culprit — the one that has committed the murder. There are a few more prompts for how the Detective cracks the case (e.g. tricks the killer into revealing themselves) and the story is brought to a conclusion.

There’s a lot more going on mechanically that I’m not going to cover here, such as the Peril system to trigger a second murder or the use of cards to generate randomness.2

Out of randomness, a story

I played The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game solo, and was surprised at how well it worked! It starts out with making completely random suspects, each with just a few bare details. Then you add in clues that have to be linked to the suspects. Then you add in more answers which link the clues and the suspects even more.

Little by little, a narrative started to form, largely driven by the random movements of the Killer token. By complete chance, some suspects received more attention and related clues than others. Some developed more connections than others.

Even though the culprit was selected at random, it didn’t feel out of place because ultimately all suspects were connected by a web of clues.

In the end it felt very much like one of those police evidence boards with notes and photos connected by lines of red string!

Solving mysteries with emergent narrative games

The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game isn’t the only game that uses this method. Other examples include Waffles for Esther and the Hints and Hijinx system, both by Pandion Games. Brindlewood Bay is Murder, She Wrote crossed with H.P. Lovecraft. The Gumshoe system by Pelgrane Press is focused on finding clues and knitting them together to solve a mystery [EDIT: Gumshoe is not fully emergent and the clues are pre-planned. Still worth a mention here, I think. —EP].

While many games successfully achieve emergent mysteries, it remains a difficult design problem.

Challenges

Coherent story: Without a pre-defined answer to the mystery (e.g. the murderer), it is hard to maintain a coherent story. If the narrative is too random, the story simply won’t make sense.

Satisfying conclusion: Even if the story makes sense, it can still lead to a conclusion that isn’t satisfying. Simply springing the answer out of nowhere or having to struggle to make it fit the existing story will sap the fun from the end of the game.

Uncertainty vs. player agency: Emergent narratives usually require some form of randomness to be injected into the game, often in the form of dice or cards. This must, however, be balanced against player agency and choices that matter. Too little randomness and the players are just making their own mystery and solution. Too much randomness and the mystery becomes incoherent.

Dynamically generated clues: With an emergent narrative, the clues can’t be generated ahead of time. This means they are generated on the fly, often using random tables or other methods. Random tables and prompts must be carefully designed so they produce meaningful, interesting, and coherent results.

Solo and GM-less play: It can be extremely difficult to design a murder mystery game that supports solo play. By definition, the solo player is also running the game and therefore has access to all information. The only “hidden information” is that which is generated randomly.

Possible solutions

Relationship frameworks: The The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game 5x5 grid is a really smart way to handle this. By using a checkerboard pattern of suspects and clues, it ensures that a web of connections is built. No suspects are left out.

Increase player agency: While The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game uses random Killer and Sleuth tokens to decide where clues/answers appear, an opportunity exists to use player choices in other games. Choosing where to search or who to interrogate can help support the narrative.

Asymmetric information: In multiplayer games, hidden information is a great way to make the mystery more interactive. Players might pull random clues from the same system to ensure they are coherent, but each player only knows a piece of the whole.

Flexible endings: The hardest part of the design is wrapping up the mystery and tying up any loose connections at the end. The system needs to be flexible enough in the final phases to handle any possible random results.

It’s a tricky design space, but that also makes it exciting and interesting!

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Emergent narrative can be part of any game: Board games, video games, and TTRPGs can all be designed to support emergent narratives and unique storytelling. Player agency, randomness, and a lack of strict goals are some of the key requirements.

It’s a challenging design space: It’s difficult to design a murder mystery game that feels emergent and unscripted. This is even more true if it’s a solo game. Ensuring that the game has a coherent story with interesting clues and a satisfying conclusion is no small task.

But solutions exist: The Locked Room Murder Mystery Game and the other examples above (e.g. Brindlewood Bay) are great places to start. They each approach the design challenges in a different way, so there is something to learn from each one. Focusing on relationship frameworks, player agency, and flexible endings can help.

What do you think? Which board games or TTRPGs have you played that had the most flexibility, allowed for emergent narratives, and felt completely unscripted? Do you have a favorite murder mystery game?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. If you use Affinity Publisher for designing games in print, you should grab the free CMYK Color Palette by Exeunt Press. Based on Mixam’s “Color Charts and Values Guide,” it has 230 colors that work well on both screens and in print. 🎨

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

An ashcan edition is a limited, incomplete, early release of a game. Some ashcans are experimental and might not have complete rules and mechanisms. Others might be “feature complete” and fully playable, but lack art and additional content. Ashcan editions are a way to get your game in the hands of players and tested, and potentially an excellent source of feedback to incorporate into the final design.

I really do mean a lot more. The book packs a lot of rules into just twenty-one pages. Each phase ends when a certain mixture of cards is drawn, such as a full house or four of a kind. There are Peril and Answer tokens that are compared. Far too much to explain here.

This post really encourages me as a GM. I lean into emergent narratives when running games. Strictly sticking to only what what's written in the adventure module or scenario (aka railroading players) is boring. I don't enjoy these type of sessions as a player, so why would I enjoy them as a GM?

I recently was introduced as a player to External Containment Bureau. Everything was made up based on the randomness of dice rolls, player agency, roll tables, etc. It didn't have a satisfying ending. I wanted to enjoy the game, but it fell flat for some reason after the first session (out of three total). I'm not sure if the GM was too new to the system or if he left something crucial out. It has potential, so I may revisit it again in the future.

Brindlewood Bay and its cousin The Between are excellent examples of emergent mysteries, literally created by the players and verified by a dice roll, with modifiers for the number of clauses that have been tied in to the solution and the difficulty of the problem. I’m not sure why gumshoe is included though because it’s very much a “clues designed up front” system. The key idea there is that you don’t roll to find clues, you automatically find them. I know someone working on an emergent mystery inspired by the famous 5 stories, but that is still in development.