Where are the board game SRDs?

In which I ponder if the idea of a board game SRD or third-party license makes any sense. And if so, what would be required to create a culture of hacking and remixing in the board game industry.

Update: I’ve largely changed my opinion on SRDs since writing this article in May 2025. After reading reader comments both here (see below) and other places online, I can now see why SRDs (depending on how we define SRD) can be at best unnecessary and at worst harmful. Does that mean all SRDs are bad? Certainly not! But be sure to check other opinions after reading this article before you decide. — E.P. 2/6/2026

Last week we looked at the minimal game design of Compile: Main 1 and how it’s use of dense component information allowed for a rather deep game to fit in a single deck of cards.

This week we are exploring a topic that I think about quite often: Why are there so many TTRPG SRDs and third-party licenses but almost none in the world of board games?

System reference documents (SRDs) describe the core mechanisms of a game. When combined with a third-party license, it allows people to create new content for the game. It might even allow creators to hack and remix the game into a new game of their own. Do SRDs make sense in the realm of board games?1

TTRPG system reference documents

If you regularly play tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs), you no doubt have heard of system reference documents (SRDs). They are documents that contain the core mechanisms of a given TTRPG. Sometimes they include only mechanisms and no thematic elements, but other times they include things like monsters, equipment, and spells.

At one end of the spectrum, the Carta SRD is extremely bare bones and mostly describes the mechanisms to use when making a game. Other than using terms like “survival mode” and “collect mode”, the 12-page document is essentially theme-less.

In contrast, Gila RPGs’ RUNE Creator Kit reads more like designer’s notes. It is a self-described “long document that outlines how to create all the things you might want to create for RUNE.” While many SRDs read like technical documents, the RUNE Creator Kit openly rejects this in its preamble:

This isn’t a technical document in the slightest. There is no “correct” way to do game design, which means I’m just going to write this like I’m sitting at the table with you, having a chat about how RUNE stuff is made.

Both are good examples of system reference documents even though their styles are extremely different. Both are popular and have been used by creators to make new games and new content for existing games.

The D&D SRD and OGL

Of course, it is impossible to talk about TTRPG SRDs without mentioning the Dungeons & Dragons System Reference Document. Currently at version 5.2.1 and running for a hefty 364 pages, the D&D SRD covers how to play the game, character creation, origins, feats, classes, magic items, and monster stat blocks — all free under a CC-BY-4.0 creative commons license. It’s been around since 2000 when it was published under the Open Game License (OGL). Its release was a major event at the time and helped to reinvigorate D&D as a game, brand, and franchise.

There is much discussion that can be had around licensing, third-party content generation, the OGL, and other legal issues.2 That’s well beyond the scope of this article, and not really what I want to focus on. You may, however, want to check out Kit Walsh’s concerns about the gifts of dragons to learn more.

TTRPG third-party licenses

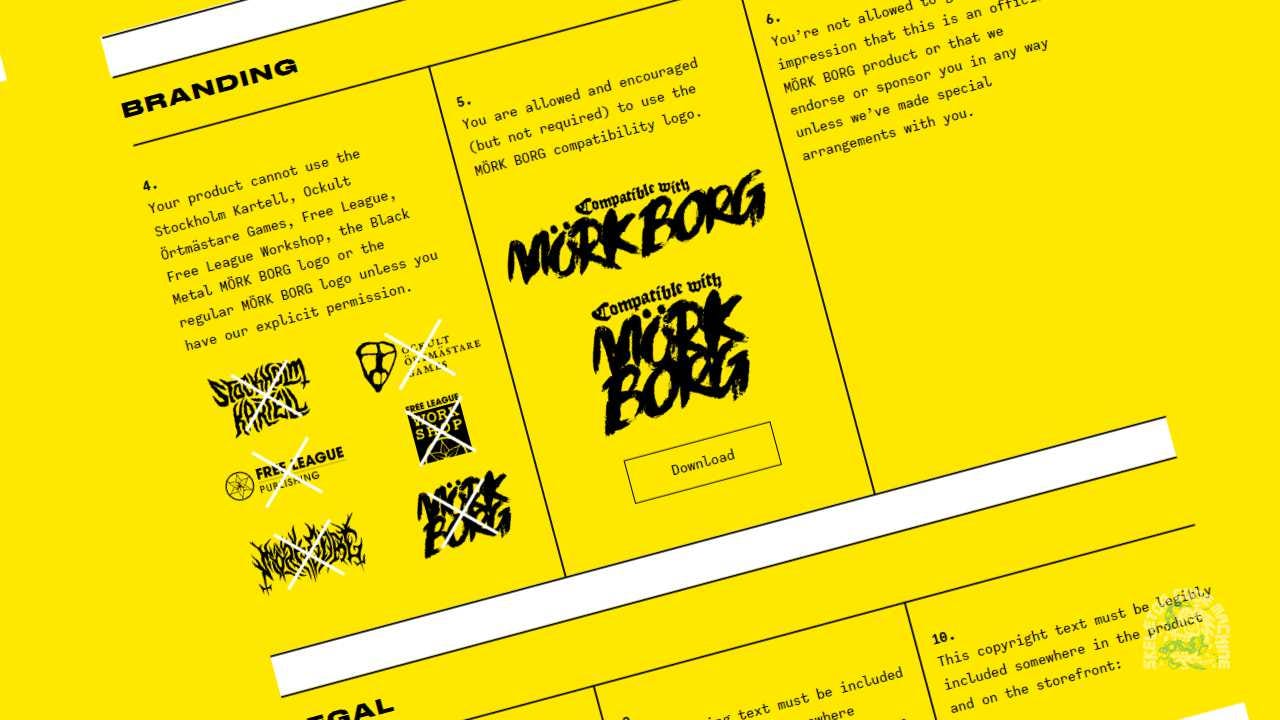

Similar to SRDs and intertwined with the idea are third-party licenses for games — allowing designers and players to make additional content for the game. Some licenses, such as the MÖRK BORG third-party license go further by allowing full hacks and spin-offs of the core game. This includes both the game mechanisms and some of the game’s copyrightable content (e.g. location names, lore elements, etc.).

Since MÖRK BORG’s release in 2020 and subsequent rise to fame, their short and plain English (Swedish?) license style has become increasingly popular.3 Games like Pirate Borg and CY_BORG use almost word for word adaptations, while other games change the language but keep the brief style.

Like SRDs, permissive third-party licenses allow (and encourage) games to be hacked, remixed, and expanded.

Barriers to board game SRDs

So if SRDs and third-party licenses have helped popularize games like Dungeons & Dragons, MÖRK BORG, and countless other TTRPGs, why don’t similar things widely exist for board games?

Here are three major barriers to adopting SRDs in board games:

1. Design history and culture

TTRPGs have a long history of DIY culture, hacking existing works, and remixing content. The original versions of Chainmail (1971) and Dungeons & Dragons (1974) owe a lot to medieval miniatures wargaming rules and culture of the time. Roleplaying culture is often mixed with homebrew rules and handmade zines. So it makes sense that both players and designers in that culture are more comfortable with game rules being available for remixing.

I’m not sure that same culture has existed for modern (vs. ancient) board games. Instead games are monolithic works, released like one might release a book or other work of art. The expectation is that the players engage with the work (i.e. game) as it is, and not change it to suit themselves.4

2. Components and economics

By their very nature, TTRPGs require almost no custom components (e.g. custom cards, game board, etc.) and instead can easily be played with some dice, pen/paper, and not much more. Certainly, Wizards of the Coast would love to have players buy thousands of dollars worth of accessories, terrain, maps, and minis, but they aren’t required. Some TTRPGs can be played with no equipment at all. All this means that economically, TTRPG hacks and third-party content is relatively inexpensive to produce.

Board games are the exact opposite. With some notable exceptions like Button Shy’s 18-card games, most board games require large quantities of custom components. Once you include even a single deck of custom cards, the production cost of a game becomes non-trivial.5 This is probably the biggest challenge: Even if board game SRDs were to exist, what would you do with them if you couldn’t pay to produce a board game?

In addition, art is usually tightly integrated with the games. Board gamers would no doubt be confused by third-party items with a completely different art style.

3. No jumpstart events

Love or hate Wizards of the Coast and Dungeons & Dragons, but the release of the System Reference Document and OGL in 2000 was a big deal. Having a large company make a move like that had a ripple effect across the industry. It is now almost an expectation that large TTRPG publishers provide third-party content support and licensing for their games. For all of its flaws, it was a jumpstart event that changed the industry.6 While perhaps not at the same scale, the release of MÖRK BORG’s third-party license acted as another jumpstart event.

I’m not aware of any similar events that have occurred in the board game industry. One could only imagine that if Asmodee or Stonemaier launched a game with an SRD and/or third-party license, it would be a seismic event in the industry. But this has yet to happen.

But deck-builder games!

When I’ve talked about this with friends, they have pointed out that you don’t really need board game SRDs because designers already iterate on other games. Dominion (2008) started a deck-building revolution that saw countless mechanically-similar games being created. Likewise the similarities between deck-builders like Star Realms (2014) and Shards of Infinity (2018) are clear. Mechanisms can’t be copyrighted, so why bother with an SRD?7

While these are certainly examples of designers taking inspiration from others and making the game their own, to me, they are different. Care must be taken to make the game different enough as to avoid accusations of plagiarism, even if only in spirit and not legally. In a theoretical world of board game SRDs, the designer/publisher would encourage others to hack and re-theme their games.

Toward board game SRDs

What would it take to make board game SRDs and/or third-party licenses more common? We could start with this:

Modular game engines: Modern board game designers often work hard to create bespoke rules with tightly integrated theme and mechanisms. This creates great games, but makes them monolithic and hard to hack. To facilitate an SRD, the board game’s design would need to be focused on a modular engine with interchangeable themes.8

Creation of documents: It’s hard enough to fund a team to build a great board game, so adding the additional labor of creating SRDs is tough. Still, the ability to create and share clearly written documents that can be used by third-party creators is required for adoption.

Legal framework: I am not a lawyer, so I won’t claim to know what the right answer is for this one. I do know that, as a non-lawyer, I appreciate the simple and easy to read format of the MÖRK BORG third-party license. Larger companies with legal teams will no doubt create much longer licenses.

Building a third-party community: It’s one thing to make a modular system, create an SRD, and publish it. It’s quite another to get creators to use it and to make stuff. A concerted effort would need to be made to market and publicize the ability to make third-party content.

Ultimately the adoption of anything like TTRPG SRDs and third-party licenses in the board game world would require a significant cultural shift — recognition that sharing systems expands markets. It would require experimentation of a particularly bold (and potentially risky kind) that is unlikely in the current climate and economic situation.

Risk vs. reward

If adopting an SRD and/or third-party content creation license would add more work and complexity to an already tough board game design process, why bother?

With the risk comes the potential for some significant rewards:

Community support and growth: One need only look at the explosion of indie TTRPG games on itch.io to see that game fans often want to become game creators. Creating new materials for a game allows players to go beyond just playing the game. This self-expression leads to a deeper emotional investment and the desire to tell others about it.9 MÖRK BORG spread not because of a multi-million dollar ad campaign, but rather due to word of mouth.10

Sustainable game ecosystems: The explosion of third-party D&D 5e content was possible because of the OGL, which is why the proposed restrictive changes caused so much controversy. A quick look at DTRPG or Kickstarter shows how pervasive the system is and how it has a life of its own. Most of today’s hobby board games have a short lifespan as gamers focus on “the cult of the new.” Third-party content can keep a game relevant well beyond the original hype cycle.

Tools for education and new designers: Building interest in playing, designing, and making board games has long lasting benefits for the board game industry. Removing barriers to creation and providing a way for hobbyists, students, public libraries, and educators to hack and remix existing game frameworks is a way to accomplish this. There is an active culture of game jams in the TTRPG world that pulls new people in to the community. A similar culture of shared content game jams would benefit board games as well.

These benefits aren’t guaranteed. There are hundreds of games with SRDs that never achieve the critical mass required for a community to grow. The barriers listed above (particularly the need to produce physical components) are real.

Still, imagine what it might look like if there were a Love Letter (2012) or Mint Works (2017) SRD and third-party license.

But what’s the point?

I think about tabletop games a lot. I also happen to be in a unique position of being fairly deep into both the TTRPG and board game worlds — and convinced that the dividing line between the two isn’t as clear as some might think.

Consider this article my love letter to the culture of open third-party licenses, hacking, remixing, and creating content that exists in the indie TTRPG world. It captures some of what is best about art and people who want to make stuff. It is only natural that I look at board games and wonder what they might look like in a different setting, different culture, and different economic model.

The MÖRK BORG third-party license has led to the creation of Pirate Borg, Vast Grimm, and countless others. I personally run MÖRKTOBER each year as a celebration of the culture of creativity that has sprouted up around the game. I run free library classes that encourage participants to use SRDs to make their own games.

It is worth at least thinking about what lessons could be learned and applied to the world of board games… even if it never happens.

What do you think? Do the ideas of SRDs and third-party licenses translate to board games, or is this all nonsense? Are you aware of any board games that have something like an SRD? Is the need for physical components the biggest barrier?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Searching for “board game SRD” yields basically no results on Google.

The proposed OGL changes were extremely controversial.

One could make the case that part of MÖRK BORG’s rapid spread was due to the ability of fans to create new content for the system via the license.

Two categories that might be exceptions to this: (1) historical wargaming culture seems to be quite into homebrew rules for scenarios and/or alternate rules, (2) classic card games must have experienced a culture of hacking/remixing to have so many versions of whist and other trick-taking card games. Still, they don’t have formal SRDs or third-party licenses.

A single 54-card playing card deck might cost $9 - $17 each when produced in quantities under 100, excluding shipping. Costs significantly decrease when producing over 5000 copies (~$1.75 each), but either way it is a significant cost vs. a PDF-only TTRPG.

I don’t love calling this a “jumpstart event” but I couldn’t think of a better term.

This was one of the points made by Kit Walsh in response to the OGL controversy; specifically how the OGL claimed to permit use of game mechanisms: “You’ll notice that these are the elements that are not copyrightable in the first place. So the only benefit that OGL offers, legally, is that you can copy verbatim some descriptions of some elements that otherwise might arguably rise to the level of copyrightability.”

Again, historical wargames come to mind. The Commands & Colors series by Richard Borg achieves something much like a modular game engine. While each game does modify the rules, the core of the game is the same in Command & Colors: Ancients and Commands & Colors: Napoleonics. Theme can be swapped with relative ease.

This culture does exist to some extent already on the BGG forums for games. There are many fan-made rules, player aids, and other content.

This is as far as a I know. If it turns out Stockholm Kartell did spend millions, please let me know in the comments. :)

I think there might be a scene in the boardgame community which could have potential to follow the TTRPG community's footsteps when it comes to promote a culture of hacking and remixing - the Print-and-Play one. They are already used to working with easily accessible materials, and the DYI spirit is much more entrenched already than in the rest of the boardgame community.

Very nice discussion of the relevant issues here. I absolutely agree that a 3PL can turn a good game into a great game by building a community around it. I think the biggest issue for board games, as you mention, is the custom components. Imagine Scythe had a 3PL, and you wanted to make a new faction for that game. Well, at minimum you will need to produce a cardboard player mat with the abilities on it, and possibly a custom set of mech minis to go with it. Anything less than that (i.e. just publishing the info and expecting people to use it with the components they have) would not feel like a sellable product. It would feel like fan fiction, similar to what people already post on BGA (as you mention in your footnotes). Or, say you want to publish a new faction/color/boss for Hero Realms. Well, that’s at least a custom deck of cards, which is not a small purchase. Could people do these? Of course. But would this build a community of dozens or hundreds of creators? Probably not.