Stunts, horsepower, and driving off the map

Exploring the use of fixed-perspective maps in TORQ, a rallyraid roleplaying game

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, an ENNIE-nominated and award-winning weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Check out Public Domain Art and Fragile Games to get started. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration delivered to your door each quarter!

Two important updates first:

📝 Did you take the Skeleton Code Machine Annual Reader Survey yet? Takes just a few minutes and helps guide the future of this newsletter!

📦 TUMULUS shipping: The prints arrived and TUMULUS is now shipping! In fact, some packages have already reached their destinations! There are still a few TUMULUS Founder subscriptions available, so sign up if you want the extras!

Now let’s talk about fast cars…

I’ve had my eye on TORQ for quite a while, particularly due to one line in the introduction: “TORQ is a mix between a board game and a roleplaying game.”

As with Inhuman Conditions, I love games that blur the line between board games and roleplaying games.1 So when I had a chance to pick up a signed copy of TORQ at PAX Unplugged, I jumped at the chance.

There is so much to talk about with the game, but I want to focus on just one specific mechanism — the road.

TORQ rallyraid roleplaying

TORQ is a post-apocalyptic “rallyraid roleplaying” game by Will Jobst:

Race along the open road, collect the pieces of a changed world, and build something new together. You’re a driver, with a license to go anywhere and the grit to handle anything. There’s gas in the tank, an x on a map, and open road for miles.

Players create drivers and cars, using random tables to choose “what’s on the dash”, “what’s in the back”, “what’s under the hood”, and the chassis. Instead of a simple health stat, players have Horsepower (HP) that is a combination of Health, Crashes, and Speed (0-60 time).

After choosing a driver type (e.g. Aggie, Archive, or Modem), starting packages provide “stunts” that can be selected. The Aggie gets a Great Diet with extra health when rolling HP. The Modem has a Jailbreak action that can place a lock or lure on a target.

Gameplay in TORQ alternates between The Road and The Reststop — with some similarities to how Lancer handles combat (tactical, board game style) and non-combat (narrative, RPG style).

The Road is the part we will explore.

The road

Games like Lancer and Rune use tactical maps for part of gameplay, and TORQ does this as well:

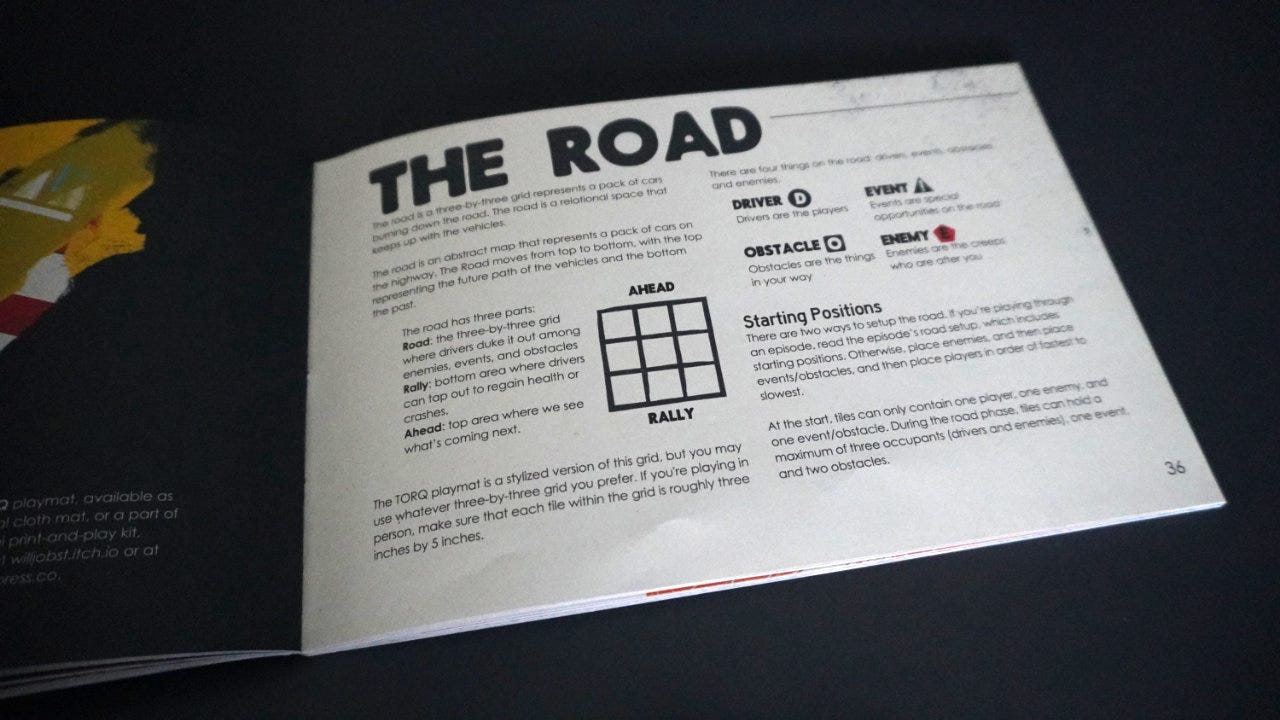

The road is a three-by-three grid representing a pack of cars burning down the road. The road is a relational space that keeps up with the vehicle.

The interesting part is how all the action of cars speeding down an endless road is contained on this tiny 3x3 grid. It acts as a fixed frame of reference — a camera that stays aimed at the cars while the road speeds past.2

The road map is made of three parts:

Ahead: The top area above the grid representing the road to come — this is what is coming next.

Road: The 3x3 grid where the action happens, including drivers, enemies, events and obstacles.

Rally: The bottom area below the grid representing the road in the rear view mirror. Drivers can temporarily drop back into the rally to regain health.

Each square (i.e. tile) on the grid can hold three occupants, an event, and up to two obstacles.

When on the road, drivers can take two actions on their turn. This can be any combination of: move, collide, attack, or perform a stunt (e.g. the Modem’s Jailbreak action above). Slam into other drivers to cause a collision. Attack enemies to reduce their health. Perform stunts.

But the road keeps moving.

The flow of the road

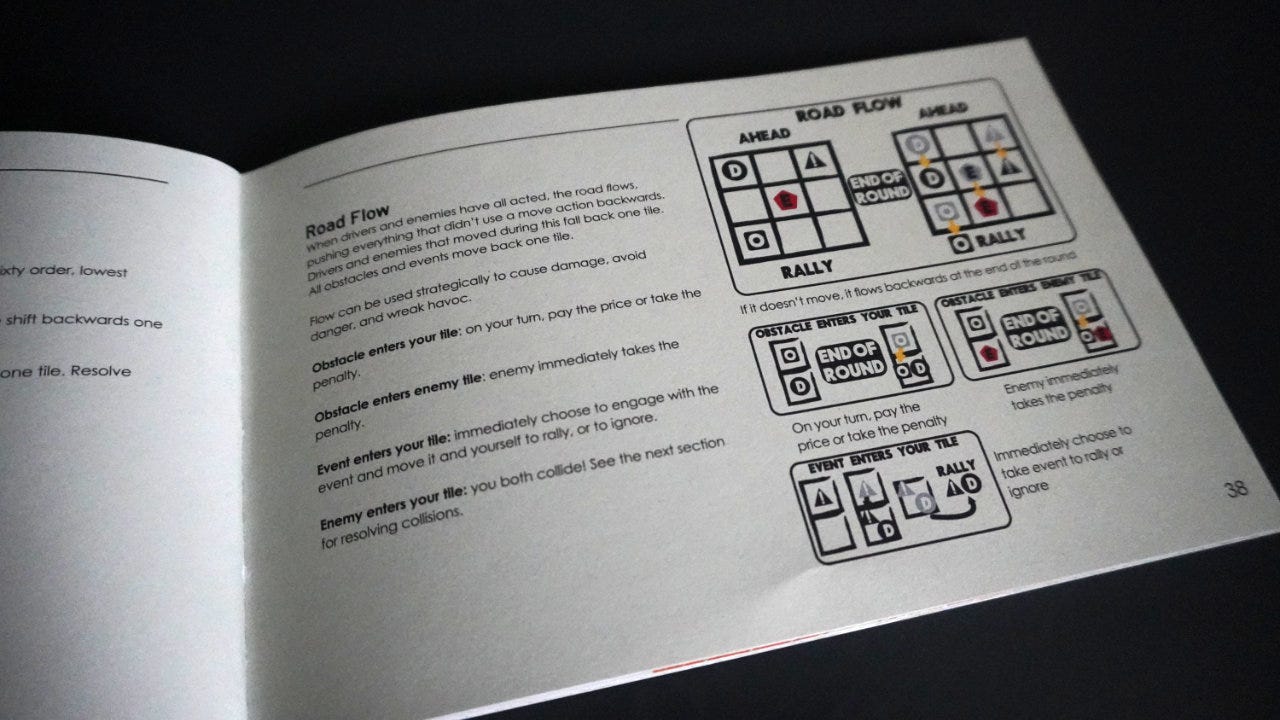

After all drivers have taken their actions, the road flows — everything that didn’t move will slide one tile down on the map. Any drivers that did move, will stay in the tile where they ended the round.

This can create havoc as obstacles might enter your tile (or the tile of an enemy). Events that were ahead may now become available. Moving into a tile that already contains multiple drivers causes a collision involving everyone.

If your driver was in the bottom row of the 3x3 grid and choose not to move, they drop into the rally area. They get a chance to recover, but also can’t engage in the action until they move back onto the main road.

It’s a really interesting system that makes position matter.3 Not only do players need to worry about their current position, but also how the road flow will change the map at the end of the round. It adds some fun tactical choices and options, potentially lining up very satisfying collisions.

Moving off the map

Any game with a map has to deal with the question of what to do when a player moves off the map. Do the edges of the map act as impassible barriers? Does the world wrap back around to the other side? Are more tiles added as new areas are explored?

TORQ’s road flow mechanism solves this in a way that keeps the table footprint under control. The grid never expands past the original 3x3 tiles. Instead the world zooms by — either move or be dropped off the bottom of the map.

There are a few board games that use a similar mechanism, but Thunder Road: Vendetta (Chalker, Myers, et al., 2023) is a recent and popular one. Like TORQ, it has a post-apocalyptic road race theme.4 The road consists of three road tiles: rear, middle, and lead — collectively known as the board. When a car moves past the edge of the lead road tile, the rear tile is removed and a new lead tile is placed. Sliding everything backward, the former lead tile becomes the middle tile and the former middle tile becomes the rear tile.

Unlike TORQ where this gives a chance to rally off the map, in Thunder Road: Vendetta all cars on the removed rear tile are eliminated.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Not just for cars: Both TORQ and Thunder Road: Vendetta make good use of their fixed-perspective, scrolling maps to simulate car-based action. This method could be used with other settings, as noted by TORQ (p. 34): “The default gameplay of TORQ includes cars — but you can just as easily podrace, cross-country ski, ride ‘em cowboys.”

Not just for maps: While this mechanism works well for maps, I think it would be interesting to use it in a more abstract way. It could be used for some sort of stat tracking where the tokens are constantly sliding down and off the grid if not maintained. Degrading magic? Cyberpunk hacker tracing?

Think about table footprint: Not everyone has a giant gaming table to use when playing board games or TTRPGs. Using mechanisms like the scrolling map keeps the play area reasonably constrained, making it more accessible to those with small tables.

If you can think of other games that use a similar tile scrolling mechanism, please share in the comments! There is a board game that does this with some sort of cloud or airship theme, but I can’t think of the name of it!

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Take the Skeleton Code Machine Annual Reader Survey before December 31, 2024. I’ll probably post an aggregate data summary early in the new year.

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

The distinction between “board game” and “roleplaying game” is more of a spectrum than a clear line. Certainly it would be hard to call a game like Go or Hearts a roleplaying game, just as it seems odd to call You are a Muffin a board game. Most games fall, however, somewhere in between those two — The King’s Dilemma and Emberwind RPG are examples.

Some comparisons can be made between this 3x3 road grid mechanism and side-scrolling video games. Both maintain a perspective locked on the player while the background changes, creating a thematic sense of movement through a world.

Making position really matter during tactical portions of a TTRPG is a tricky design problem. If left unsolved, combat can degenerate into combatants running up to each other and just pounding away until one drops. I wrote about this idea in the MECH WEEK: Combat article, using Lancer as an example.

Rebel Minis uses a similar mechanic of a fix frame on the pack or as they advertise “In Win or Go Home! it’s not where you are on the track, but where you are in the pack. In this game, the cars are grouped into a pack and the pack moves around the track. What’s important is where you are in relationship to the other vehicles in the pack. EVERY TURN, you have to make decisions about passing or being passed, pit stops, drafting other cars, tire wear and performance loss. You’re always involved during every turn and things can change quickly. You might start the turn in last place but end it in first! Now, can you hang on to that position?”