Call to Adventure

Casting runes and taking suboptimal turns to achieve your destiny

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Last week we looked at adapting public domain works for use in your games, and before that we looked at the narrative design of The Skeletons.

This week, we are looking at Call to Adventure with it’s unique alternative to dice rolling and interesting story-building.

Call to Adventure

In Call to Adventure (O’Neal & O’Neal, 2019), players attempt to build the story of their characters:

Make your fate! Inspired by character-driven fantasy storytelling, Call to Adventure challenges 1-4 players to create the hero with the greatest destiny by acquiring traits, facing challenges, and overcoming adversaries.

You begin with three cards:

Origin: A simple background that also provides an in-game benefit or special power (e.g. Performer).

Motivation: What drives your character, also providing an in-game benefit (e.g. Thirst for Knowledge).

Destiny: A third card that shows what you will become and usually impacts end-game scoring (e.g. Wise Master).

At the start of the game, only your Origin and Motivation are face-up and public.

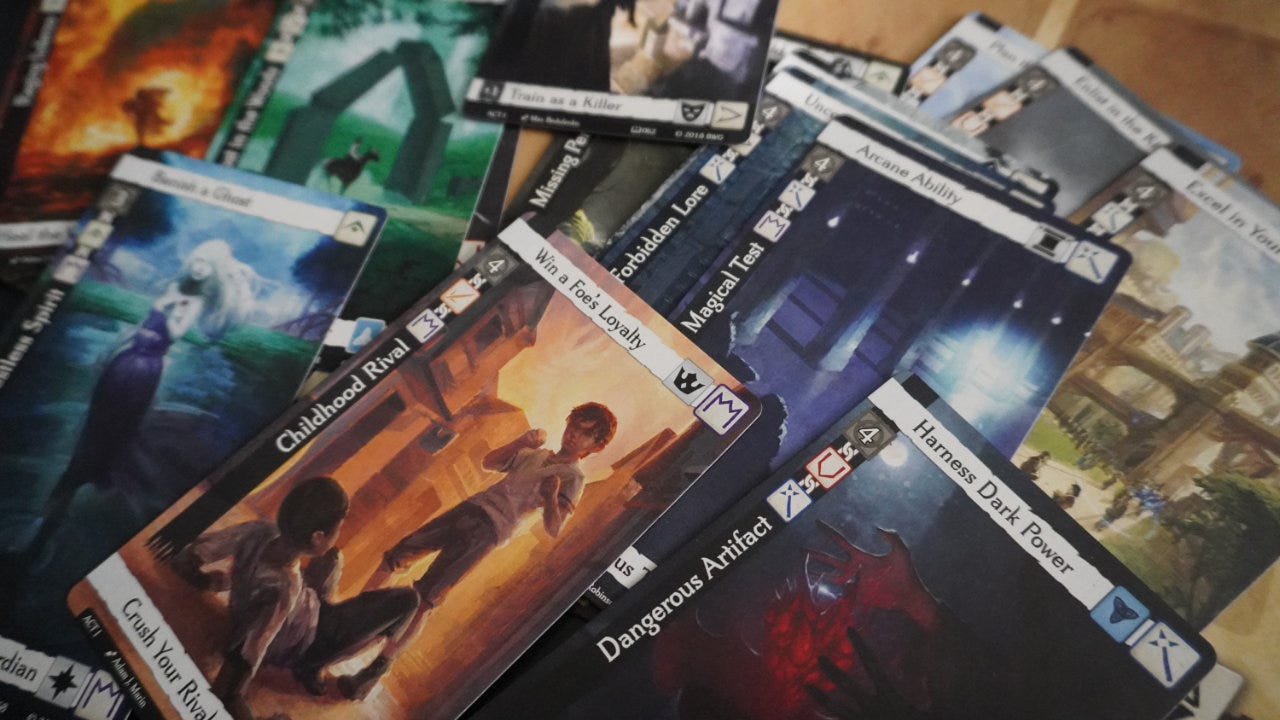

Each turn you select one card from a tableau divided into three acts. Cards will either allow you to gain traits (e.g. Brave) or attempt challenges (e.g. Find a Lost Child). Each of these add to your character’s story by collecting the cards.

After one player has gained three Trait/Challenge cards under their Act III Destiny card, the game ends and the player with the most Destiny points wins.

Reading the runes

Call to Adventure uses a unique rune casting system instead of common methods like dice or cards. The game comes with 24 plastic runes, three of each Ability Runes correlated with character abilities:

Strength,

Dexterity,

Constitution,

Intelligence,

Wisdom

Charisma.

There are also three Core Runes that are used in every challenge attempt, and three Dark Runes that add to your success, but might also increase your corruption.

Each challenge has a difficulty level ranging from 3 - 8.

To attempt the challenge, you gather the three Core Runes, any Ability Runes that match the type on the challenge card, and then any Dark Runes you decide to purchase. Toss the runes on the table, and add up the results.

If the result is equal to or greater than the challenge value, you win and can take the card, adding it to your character.

Rune math

Mechanically, the runes act like two-sided dice (d2) with the following properties:

Core Runes: Three available for every challenge. Either +1 or +0 as a result.

Dark Runes: Up to three may be purchased with XP. All three are either +2 or +1, with a chance to increase your corruption.

Ability Runes: Up to three of each ability type. Can only be used on challenges that allow that specific type to be used. The first two Ability Runes are +2 or +1, and the third is +2 or +0.

If you attempt a challenge with a difficulty of 4, you would throw three (3) core runes and any matching Ability Runes you have. You might also pay to get a Dark Rune. Throw them all and if the result is 4 or higher, you win.

So what is your chance of success?

Interestingly, the rulebook has a table in the back called Rune Probability that gives some information:

“Because Call to Adventure’s rune system is so unique, it can be helpful to understand the probabilities involved. Here’s a look at the minimum, average, and maximum value for common combinations of core runes plus Ability/Dark runes.”

It does a good job of showing how the first two Ability Runes and Dark Runes have a large impact. Because they can’t result in a zero, they are guaranteed to be at least a one. Get enough of those and you have a guaranteed success!

The table doesn’t really show, however, your probability or chance of success. So let’s take a look!

Simulating casting the runes

I’d rather know the chance of success like the table in John Company: Second Edition rather than the min/avg/max table in the rulebook.

So let’s use some Python!

The code above allows me to make a list of runes, where each rune is defined by a list of two digits. For example, a Dark Rune that is either +2 or +1 is [2,1] in the code.

Then we simulate casting the runes vs. the difficulty target for each difficulty from 3 to 8, and add up the wins/losses. And here are the results:

Note that the runes cast match the ones in the rulebook table. The results would be different if you used the third +2/+0 Ability Rune for any single ability.

A high chance of success?

One thing that shows up in the BGG forums for Call to Adventure and it’s reimplementations is that challenges might be too easy. I haven’t personally found that to be the case, but other’s have. Why might that be?

One reason might be how impactful each additional Ability Rune can be. If you look at the chart, it’s very polar with little middle ground between the green and red zones. Almost half (42%) of the grid is in the green at 80% chance of success or higher. An almost equal amount (38%) is in the red with a 20% chance or success or lower.

This means if you got your Ability Runes early or have the XP to buy Dark Runes, you can sit comfortably in the green zone and know that you will win almost every challenge.

Conversely, if somehow you made it to Act II or Act III with two or less Ability Runes, you won’t have much chance winning a single challenge.

What my character would do

As always, how you feel about Call to Adventure depends on what type of player you are and what kind of fun you want to have.

If you are looking for a competitive game or a hard challenge, it might not satisfy those desires. If, however, you are seeking fantasy, narrative, and expressive types of fun, it might satisfy them as well.

In my experience, Call to Adventure succeeds at the table because it does what few board games can do. It gets players to make choices that aren’t based on what will win the game. Instead, I’ve watched players intentionally make suboptimal choices because, “That’s what my character would do.”

This is a fascinating phenomena to me, and sits at the heart of my love of blending TTRPGs and board games. While it’s common (perhaps required) in TTRPGs to make choices matching “what my character would do” it’s a rare thing in boards games. It’s exceptionally rare in board games with victory points and an explicit winner at the end of the game.

One of the few other examples of this that I can think of would be The King’s Dilemma (Hach & Silva, 2019). If you can think of others, please share in the comments!

Suboptimal choices

This is where I think Call to Adventure is a really interesting game. What really stands out, is that somehow, by allowing the player to slowly accumulate bits of their own story, they get drawn into their own character.

They might start out just as a “performer” with a “thirst for knowledge” but each little decision on which card to grab from the tableau entrenches them a little deeper into that persona. By the end of Act III, they might be so invested in their character, they are making choices that actively deny them a victory, just to complete their story and destiny in a satisfying way.

This, to me, is the true test of how well a board game builds a story, narrative, and sense of involvement in a character or faction. When you start to see players make suboptimal choices on purpose because “that’s what my character would do,” you know you have achieved something special.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Hide the stats: I’m increasingly convinced that while the designer should know the exact probabilities behind their design, it usually makes sense to hide this from the player. The table in Call to Adventure is probably a good way to show some outlines of the math, without revealing too much. Having a detailed chance of success table might sap the fun of casting runes.

Consider unique resolution systems: The challenge resolution system in Call to Adventure could have easily been replaced with dice. Would it be as much fun to play? Perhaps not. Using Jenga towers, runes, and other weird resolution systems is more than a gimmick. It helps to build a specific player experience.

Suboptimal turns are a sign of success: If you want to make a board game where players are highly invested in the narrative fantasy of their character or faction, watch how they take their turns. When they care more about narrative than winning, you might have hit success.

We’ve looked at the question of if players should know their exact chance of success in games. I’m starting to think the answer is “no” but I could be convinced otherwise. What do you think?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Exeunt Press will be at MEPACON April 19-21 in Bethlehem, PA. Tickets are available. Stop by the booth, say hello, and get some games!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Very nice explanation! I played this recently, and we found the challenges to be quite easy. In fact, between the two players, only 1 out of 17 challenges faced was failed. However, I will say that neither myself not my opponent was really playing for the story. We were choosing challenges based on what we could win, not on how it would develop our characters. Playing this way, it's easy to stay "in the green" on your probability chart and race straight to the finish, but that's probably not be the type of play (or player) this game was designed for.