Dungeon geomorphs

Using connected tiles to generate dungeons and terrain

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Hello and welcome to any new subscribers that I met at MEPACON over the weekend! All the previous Skeleton Code Machine articles are available in the Archive, but here are some popular ones to get you started:

Public domain art resources (two part series)

What kind of fun are you having? (three part series)

Last week we looked at Sail and trick-taking games. This week we are looking at a mini dungeon crawling game called Light in the Dark.

Nominate Skeleton Code Machine for a CRIT Award: The CRIT Awards are accepting nominations until May 31. If you enjoy reading Skeleton Code Machine each week, nominating it for "Best Blog or Article Written in the TTRPG Space" is a great way to show your support! Nominate Skeleton Code Machine!

Light in the Dark

Pest (Nielsen & Starck, 2024) is a plague-fighting euro-style board game that recently funded on Kickstarter. A solo dungeon crawling board game called Light in the Dark (Starck, 2023) was included as part of some of the backer rewards.

According to BGG, Light in the Dark is a reimplementation of Micro Dungeon (Starck, 2022), rethemed to fit the plague doctor world of Pest. Reading through the Micro Dungeon rulebook, the similarities to Light in the Dark are clear:

You reveal random, connecting dungeon tiles to reveal the map.

You encounter monsters that must be fought.

You can collect useful item cards.

You must collect keys to unlock doors.

Gameplay is divided into player / monster phases.

There is a boss monster that must be defeated.

In Light in the Dark, the keys are rethemed to “herbs” and the doors are now plague-stricken “villages.” There are some other mechanical changes, very nice production/design updates, and improved three-part quest cards.

The tiles used to generate the map are interesting. So let’s take a look at those!

Geomorph tiles

A geomorph tile is a modular piece of a terrain or map that is used to create larger random or procedurally generated maps. The tiles are usually square, but are sometimes hexagonal in shape. They might feature roads, tunnels, buildings, forests, or rivers.

The key is that they can form a network of tiles via connections on the borders. Sometimes there are connections on all four edges, but often some sides create dead ends on the map. Depending on the instructions, you may be able to rotate the tiles to improve the paths.

In Light in the Dark there are eighteen geomorph terrain cards which are used to create paths through forests and connect villages. Dead ends are common, and the roads are filled with items, monsters, and herbs. One of the eighteen cards includes the boss monster location.

TSR Dungeon Geomorphs

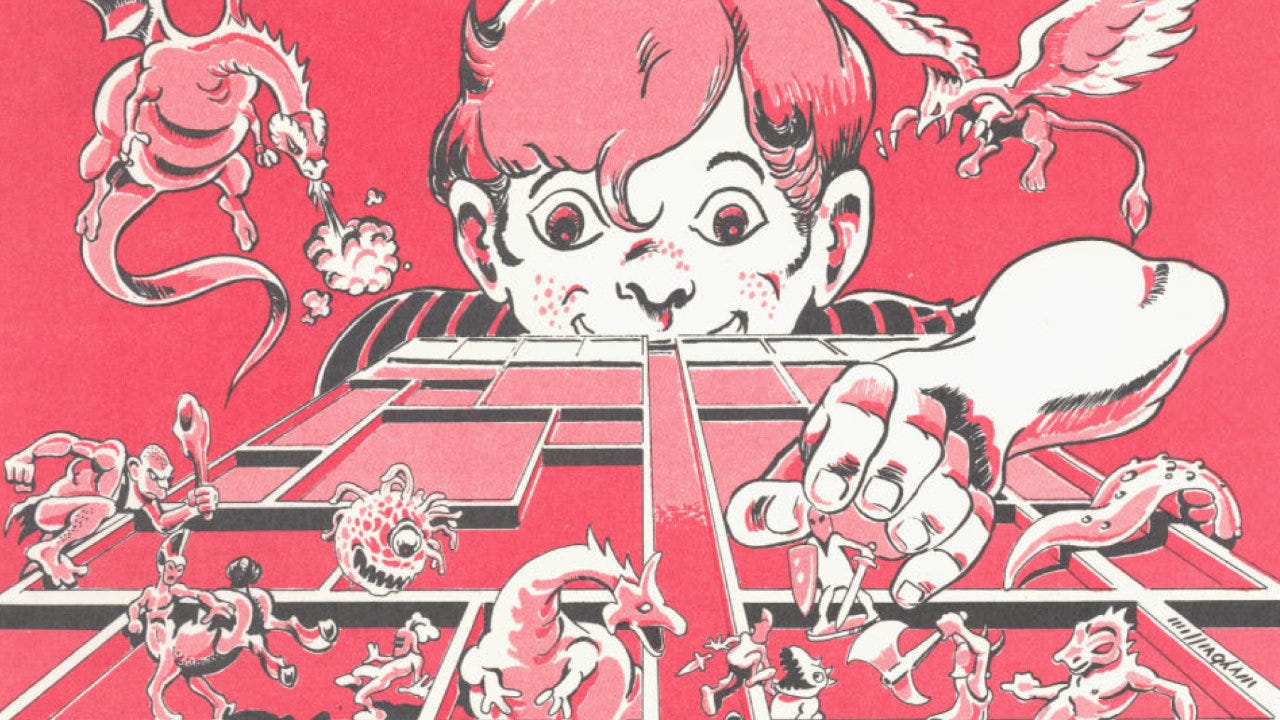

One of the earliest sets of geomorph tiles for roleplaying games was the TSR Dungeon Geomorphs designed by Gary Gygax and published in 1976. Divided into three sets, the tiles were designed to easily and quickly create 1st Edition Dungeons & Dragons maps.

The idea was that you would cut apart the many provided tiles and reassemble them in a connected fashion to form a complete dungeon.

Here is the introduction to the 1981 Dungeon Geomorphs reprint compilation, including Basic Dungeons, Caves & Caverns, and Lower Dungeons.

It contains 30 square geomorphic pieces and 15 rectangular semi-geomorphic pieces that are ready to cut out and use. With only 4 of the 45 units contained in this product, Dungeon Masters can form hundreds of thousands of maps in mere seconds! No longer will a Dungeon Master be forced to spend hours upon hours drawing a dungeon level that plays through in one session-with these geomorphs DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Fantasy Adventure Game players can look forward to infinite variety even though they may play more often.

That’s a pretty bold claim! I didn’t check the math on the “hundreds of thousands” estimate, but if you do, please leave a comment!

Many versions

There’s a short (mostly positive) review of the TSR Dungeon Geomorphs in The Space Gamer #41 (July 1981, p. 34), which seems to confirm that TSR was not the first to make dungeon geomorph tiles:

At the price, the DUNGEON GEOMORPHS are nice, but not a “must.” There are several such products out now, each in a different scale and with slightly different uses. Compare before you buy anything.

A quick search online will show a large number of geomorph tiles available:

Geomorphs by Dyson Logos (with links to others)

The Geomorph Project by Caffeinated Otter

Dungeon Geomorphs 2013 by Majcher Arcana

Blue Dungeon Generator by The Basic Expert

DCC #9: Dungeon Geomorphs by Goodman Games

Dungeon Explore Card Deck by Knights of Vasteel

Starship Geomorphs by Robert Pearce

There’s even an interesting dice-based version called DungeonMorphs by Inkwell Ideas. It’s connectable dungeon, cavern, and city maps on 1” dice. Might be fun to roll a map rather than drawing cards from a deck.

Tips for creating geomorph tiles

I’ve been looking into how to make my own geomorph tiles to expand Chthonic Metro Gods into an actual game, and here are some of the tips I’ve found:

Choose a shape: Although many geomorphs are square, they don’t have to be. The original TSR set mixed squares and rectangles. Hexagons can provide more opportunities for rotation. Mixing shapes can work but adds some complexity and limitations.

Pick a standard size: If you ever plan to produce a printed version of the tiles, look into available card shapes and sizes before you start. TGC and MPC both offer much better pricing for stock sizes vs. custom sizes. This might help you choose a consistent scale for drawing.

Decide if rotation is allowed: The Light in the Dark tiles may not be rotated, while the TSR set was intended to be rotated. Either one is fine, but you’ll need to decide early how you want to handle it.

Decide if modification is allowed: The TSR Dungeon Geomorph instructions explicitly state to add, remove, and modify doors as needed. This solves a lot of connection problems, but puts some more work on the user.

Choose a consistent theme: Because the tiles will be used together but randomly, they need to all work together. Having a desert next to a jungle next to a glacier would be a little unbelievable. So choose something that always works together, like sewer tunnels.

Align connection points: Define where the possible connection points can be on a card, and make sure they align. If you are getting them printed, you’ll need to account for bleed, safe area, and cutting drift. It gets complicated with more connection points, but makes for far more interesting maps.

Watch out for dead ends: A few dead ends are fine, and might even be preferred. The problem is if your tiles can lock a player into a small area. It’s important to err on the side of having too many connected tiles vs. too few.

Look at tile placement games for inspiration: Many tile placement board games have come up with interesting ways to ensure that randomized tiles make sense when placed together on the table. Eclipse: New Dawn for the Galaxy (2011) and Carcassonne (2000) are good examples. There is an interesting water/island example in The Game Crafter’s Design Discussion - Tiles (around the 2:23 mark).

Consider map keys: The original TST Dungeon Geomorphs was keyed (i.e. labeled) with letters in important rooms and areas to allow DMs to know where to add monsters and treasure. You don’t need to say what is in the rooms, but having some labels might be a good idea.

Playtest often: Depending on the size of your deck, you might have a very large number of possible combinations. It’s hard to beat manual testing of the tiles to make sure they line up, make sense, and can be connected without excessive dead ends.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Geomorphs are flexible: There’s a reason geomorphs have been around since at least 1976. They can be created and adapted to almost any setting or theme, and can be a source of inspiration for people running adventures.

Consider print requirements: I think it’s smart to make everything print-ready, even if you don’t have immediate plants for printing. If you are making geomorph tiles, might as well design them at 300 dpi with proper bleed and safe area rather than regret it in the future.

Combine mechanisms: Light in the Dark uses a timer mechanism to add urgency to the game and force it to end. I could imagine multiple decks of geomorph cards being used in a depth crawl. Grab some mechanisms to mix and match and you might end up with something really interesting!

What do you think? Which geomorph set would you want the most?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Investigate rumors. Gather wards and weapons. Hunt the Beast!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

I couldn't pass this one up... choosing 4 random tiles from 45 would yield 45C4 = 45!/(4!*(45-4)!) = 148,995 combinations. And because you said rotation is allowed, and the DM can add doors when needed, the true number of dungeons you could create would be many times that again.

This also reminds me of the old game Labyrinth (Ravensburger, 1986), where you use geomorph tiles to generate and change a dungeon with each turn to create paths to target objects. I'm pretty sure I still have this one!

I've got rollinkunz' DUNGENERATOR #2 which is a fantastic set of geomorphs ─ this second edition of it has the flexibility to have non-right-angled connections *and* it's got a couple of "large room" cards, which are designed to modify the shape of another card.