Place dice without rhythm and it won't attract the worm.

Exploring how Dune: War for Arrakis uses input randomness to assign dice and limit player actions, creating a unique wargame mechanism... and how this might apply to TTRPGs.

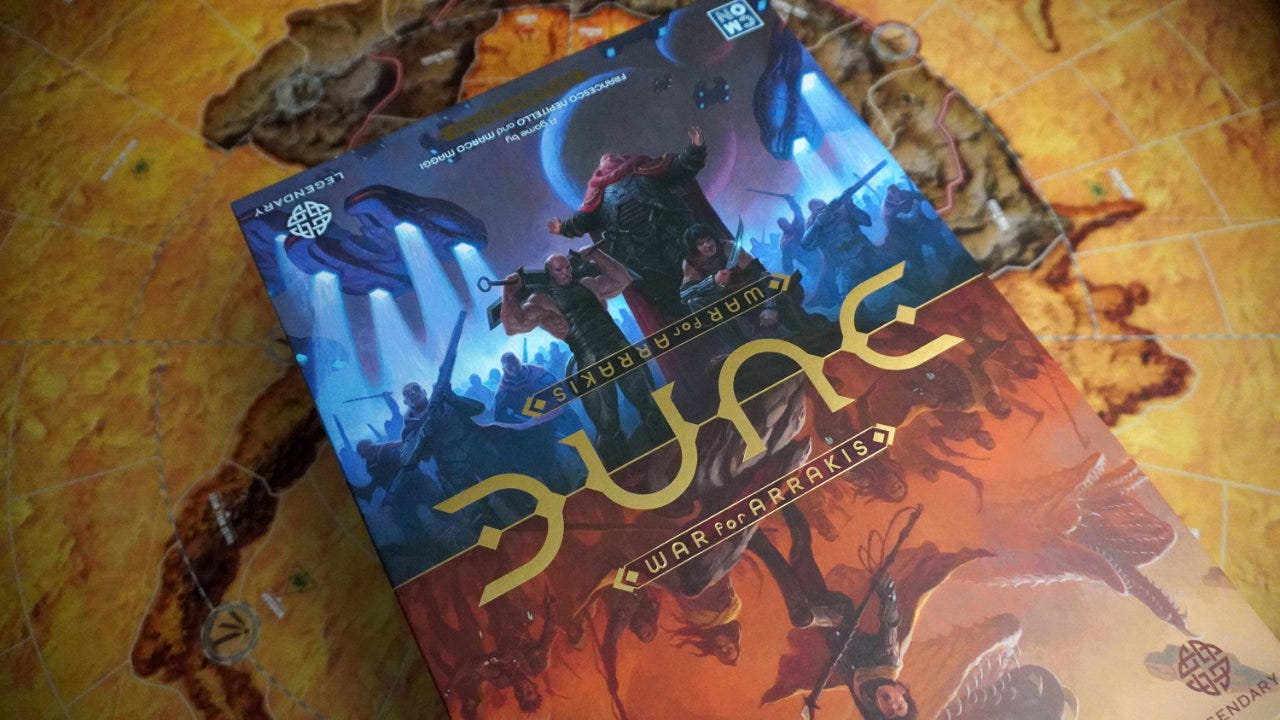

Last week we looked at The White Castle (Shei S. & Isra C., 2023) and how it uses a dice placement mechanism in a game about becoming the most influential clan during Japan’s Edo period. This week we are looking at a different variation on dice placement, this time in Dune: War for Arrakis.

Worker placement with dice workers

In case you missed last week’s article about dice placement, here’s a quick refresher:

Action drafting is a mechanism where players take turns selecting actions from a shared pool or list of actions.

Worker placement is a subset of action drafting. Instead of drafting cards or selecting actions another way, the actions are selected (claimed) by placing a token on them.

Dice placement (i.e. worker placement with dice workers) uses dice instead of meeples for the workers and the pips/color of the dice usually have a mechanical impact on gameplay.

In The White Castle, dice workers are drafted from common pools and then placed onto a common board with action spaces.1 While at higher player counts you can stack dice and take an action someone else has already taken, stacking is not allowed in two-player games. This works similarly to many worker placement games where blocking other players (i.e. taking an action space before they do) can be a significant part of the winning strategy.

There’s a completely different genre game, however, where there is no competition between players for action spaces when placing dice. All the spaces are contained on personal player boards (i.e. dashboards), only accessible to each player.

Dune: War for Arrakis

Dune: War for Arrakis (Maggi & Nepitello, 2024) uses dice in a way that, while similar to dice placement, is a fundamentally different mechanism.2

The game is a highly asymmetrical battle to control the desert planet Arrakis — home to massive sandworms and the only source of the precious spice Melange.3 Each player selects one of the two houses:

House Harkonnen: Ruthless controllers of the planet, including the main populated areas. They begin the game with more units, vehicles, and general military power at the start of the game. They win by accumulating 10 Points on the Harkonnen’s Supremacy track.

House Atreides: Fighting against the rule of the Harkonnen, they are allied with the local population of Fremen who live in the harsh desert. They have less units, but can freely move in the desert and can control the sandworms. They win by accumulating three different kinds of points on a Prescience track.

The game is rather complicated, and I won’t explain all of the rules here. Instead I’d like to focus on how each player selects their actions using a mechanism similar to dice placement.4

Using action dice on a dashboard

At the start of the Action Resolution Phase of the game, each player rolls their action dice with the following symbol faces:

Leadership: Moving and attacking with units that have an attached leader.

Strategy: Usually actions involving moving units or launching attacks.

Deployment: Adding new, active units and leaders to the board.

Mentat: Acquire and use Planning cards with special effects.

House: Atreides can use these as any other type of dice. Harkonnen can upgrade units or add vehicles to the board.

Unlike dice placement games such as The White Castle or Euphoria: Build a Better Dystopia (Stegmaier & Stone, 2013), there is no way to block the other player from placing their dice on action spaces. Instead, each player has their own dashboard with dice slots for each type of action (e.g. Leadership, Strategy, etc.).

House Atreides can have up to two dice in type of action and House Harkonnen can have up to three. Excess dice of the same face are assigned to other action types.

Then players take turns selecting dice from the available action types to use/spend them, placing them in a used action dice space on their dashboards. For example, a player might use a Leadership die to “Move 2 different Legions with a Leader” or use a Mentat die to “Draw 2 Planning cards.” No dice in that action means you simply can’t take it.

The asymmetry of the game is increased both by the Harkonnens having more dice than the Atreides, and that the Atreides can opt to use desert powers (e.g. placing wormsigns) instead of using dice as their action.

The dice are already rolled

While Dune: War for Arrakis does use additional dice rolls for combat resolution (it is a wargame after all), the action dice are rolled at the beginning of the game round. You know the results and which actions will be available. The player agency and tough decisions come from deciding the order in which you’ll take the actions.

Not only are the dice pre-rolled, there is also no choice in how they are allocated.5 The dice are rolled and placed into their respective spaces on the dashboard.

Most action types do, however, have more than one option on them. The House Harkonnen default Strategy action can either “Move 2 different Legions” or “Attack with a Legion.” Special leader cards can be slotted into each action as well, providing more (and more complex) options throughout the game.

Rethinking randomness in TTRPGs

The idea of pre-rolling dice and switching TTRPGs from output randomness to input randomness is not a new one.6 There are some systems that already do this (e.g. Omen by Spencer Campbell) and much discussion of it on forums like r/RPGdesign.

In a traditional RPG, the player decides on an action (e.g. “I attack the skeleton!”) and then generates randomness (e.g. “OK, roll a d20 to hit…”) and that randomness determines the resulting game state (e.g. “You miss.”). The player decision comes before the randomness, so this would be called output randomness.

Pre-rolling dice and allocating them is a way to switch this model to one where the randomness happens first (i.e. rolling the dice) and then the player decision is made — called input randomness.

It could work like this:

At the start of the in-game day, the player rolls a number of dice. These might be slotted into matching actions as in Dune: War for Arrakis or allocated to actions based on their choice and preference.

During the game, the players decide on their actions as usual in a TTRPG (e.g. attacking, exploring, sneaking, etc.).

To resolve the action as successful or not, they spend or use the dice that were allocated at the start of the day.

And it doesn’t need to be dice. Such a system could use cards instead, similar to Gloomhaven (Childres, 2017).

This switch to input randomness eliminates the pain of rolling a 1 on an important task, resulting in critical failure for no reason other than bad luck. It also introduces some strategic thinking regarding when to spend dice and in which order. The tension between “Do I spend the best die now?” or “Do I save the best die for later?” might be fun!

Problems with input randomness

Switching a TTRPG to an input randomness model does, however, create some potential issues:

Unusually bad dice rolls at the start might result in players knowing they are going to fail at everything they do during that day. That’s rarely going to be fun.

The number of dice rolled needs to match the number of challenges or actions experienced in the day. What happens when all the dice are spent?

It creates a decreasing decision space vs. an increasing one. Each die spent or consumed reduces the effective decision space. Eventually the player will just have one die left resulting in an unsatisfying Hobson’s choice.

For many it is the anticipation and randomness of the dice rolls that create memorable moments in TTRPGs. It may fundamentally change the feel of the game to one more akin to a board game, which may not be the kind of fun they are looking for.

None of these are unsolvable design problems, but they can be tricky to solve in a way that appeals to a wide range of players.7

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Separate action pools: Splitting a shared action pool in a worker placement or dice placement game fundamentally changes where the “tough decisions” appear. Rather than worrying about blocking the other player(s) the decisions become more about optimizing your own actions.

Input vs. output randomness: Understanding the difference between input and output randomness (and also input-output randomness) is an important aspect of game design. Knowing when to use each one is critical to creating the best player experience.

Input randomness in TTRPGs: Discussions of zero-luck and input-randomness TTRPGs seem to pop up on a regular basis. That said, I always find them to be interesting discussions and a good source of inspiration!

What do you think? Which TTRPGs have you tried that use input randomness vs. output randomness? Do you think a TTRPG that uses input randomness can retain the thrill and excitement of one that relies on output randomness?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Back in stock!!! “A beautiful, straight-forward, and inspiring book.” Get ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure, the latest guide from Skeleton Code Machine, now at the Exeunt Press Shop! 🧙

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. Subscribe to TUMULUS to get more design inspiration. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine and TUMULUS are written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. TUMULUS and Skeleton Code Machine are Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press.

For comments or questions: games@exeunt.press

There are actually some actions that can be taken on player’s personal board as well, but that doesn’t really matter for the purposes of this article.

Marco Maggi and Francesco Nepitello were the designers of War of the Ring: Second Edition (2011) and although I’ve never played that game, I hear it has some similarities. It’s currently the #1 wargame, #3 thematic game, and #8 overall game on BGG, and I hope to be able to try it at some point in the future.

I love the first Dune book and will resist the urge to explain the lore in this article. Strangely, I haven’t watched the movies yet. If you haven’t read either and don’t mind spoilers, you can read more about Melange at Wikipedia.

I’d argue that Dune: War for Arrakis is not a dice placement game which matches the mechanism categorization on BGG. The listing notes that it has action drafting, dice rolling, die icon resolution, but does not count it as a worker placement game.

The notable exception being that Atreides can use any House result as any other result.

A reader mentioned Otherkind Dice by Lumpley Games in the comments of the dice placement article. It does something similar.

Before everyone mentions Citizen Sleeper, I have yet to play the game or really even look into it. I’ve been told it’s a great game that I need to try, and I promise I will at some point!

I have seen some pre-rolling for divination focused characters, which I think is really interesting.

Would Dogs in the Vineyard's main dice mechanic be an example of input randomness?