Wargames, nostalgia, and Tactics II

Looking back at one of the first wargames I played

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Last week we looked at Bosman’s Typology of Death and the various ways death is handled in games. This week, we get nostalgic with an old wargame from my childhood.

Wargames + Worldbuilding

The early connections and shared history of wargames and TTRPGs are well known. The original 1974 edition of Dungeons & Dragons had the subtitle: Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames; Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures.

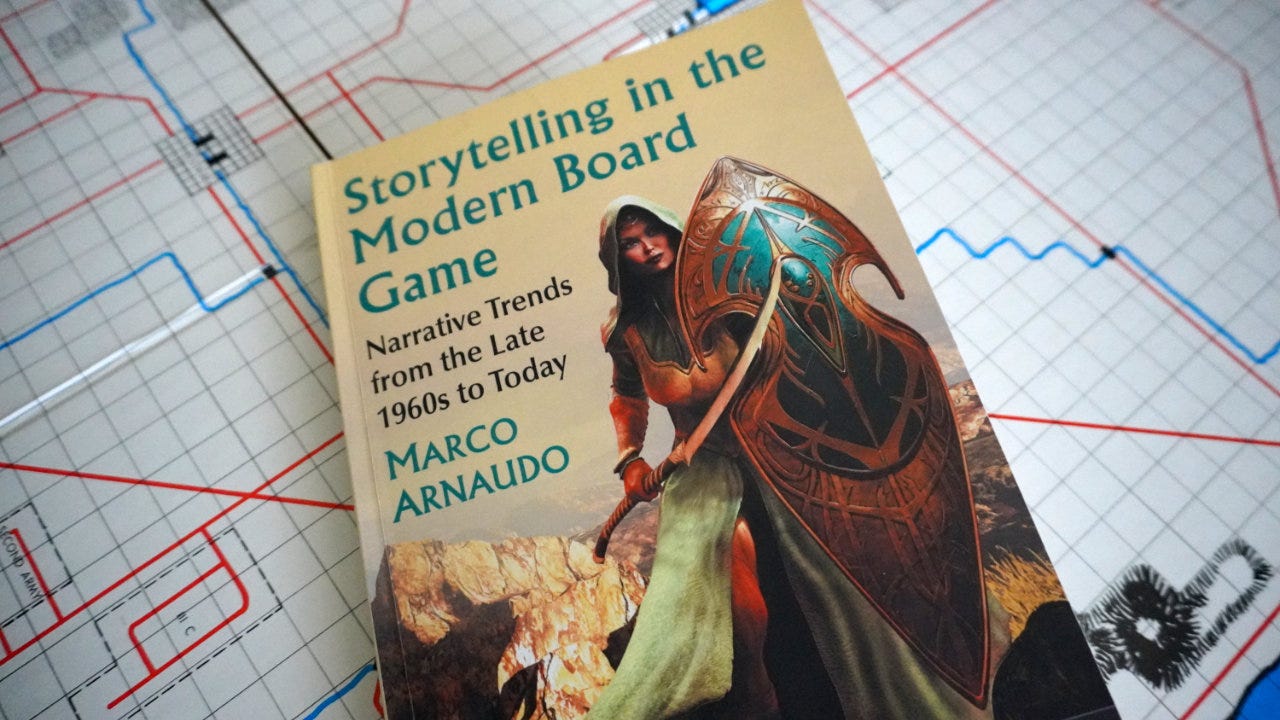

Marco Arnaudo explores this connection in Storytelling in the Modern Board Game (2018). Specifically, the chapter “The Board Games of Dungeons & Dragons” explains how D&D combined two existing systems:

Thematic Wargames: Rather than abstract games like Chess, the rules in wargames needed to be connected to the historical simulation. This attention to simulation and realism created games where the mechanisms supported the theme, which was a notable innovation.

Worldbuilding: Popular series like Burrough’s Barsoom, Lovecraft’s Mythos, and Tolkien’s Middle-earth were more than just one-off stories. They created worlds that felt alive, and where the reader was only seeing part of fantastic universe.

Take the thematic rules and mechanisms of wargames and combine them with a persistent and expansive world, and you get a classic TTRPG from the 1970s and 1980s. The overland hex map in particular would be as familiar with NATO-marked tank chits as it would be with an adventuring party of warriors.

Wargames and thematic mechanisms

I’ve been thinking about wargames quite a bit lately, as evidenced by the recent What is a wargame? And does it matter? at Exeunt Omnes. In that post, I listed a few things common to most wargames:

Map-based gameplay

Units or counters

Combat resolution systems

Victory conditions

Turn-based structure

One thing I didn’t include was thematic mechanisms or some indication that mechanisms need to be tied to the context and theme of the wargame. I think this was a miss on my part. As Arnaudo notes in the same chapter:

At the core of these wargames we find not self-referential systems like those of Mancala or Backgammon, but a serious representational imperative whose purpose is to bring realism to gameplay. If a rule is added to a military wargame, it must be because it is thematically linked to some aspect of the subject that the designer finds necessary to include.

I think “thematic mechanisms” might be a better item for the list above than “combat resolution systems.” After all, I did point out that some of the top war games (e.g. The King is Dead, Twilight Struggle) do not have direct combat resolution and may not include any combat as part of the game.

Again, definitions are usually boring, and there will always be exceptions. Understanding common elements, however, can be quite helpful when creating innovative designs.

TACTICS II

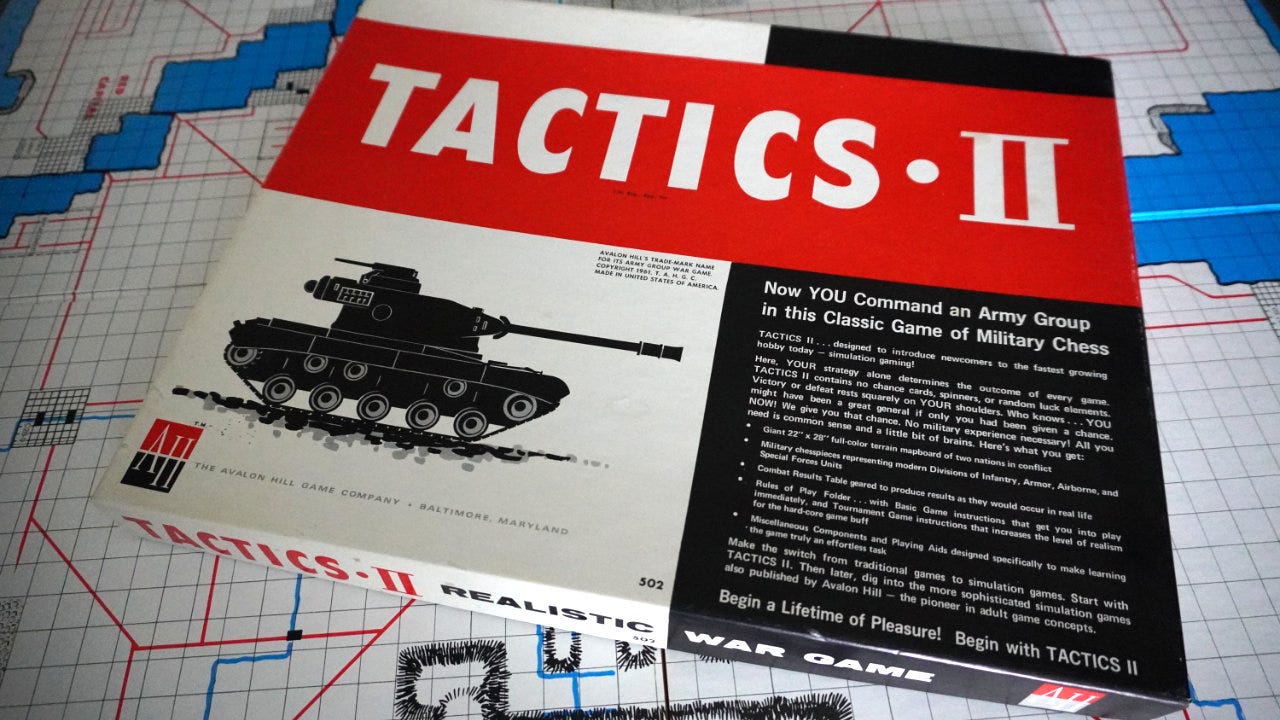

One of the earliest and fondest wargame memories I have is playing a well worn copy of Tactics II (Roberts, 1958) with my dad on our kitchen table.

A direct descendant of Tactics (Roberts, 1954) which kicked off hobby wargaming, Tactics II was advertised as “military chess”:

Now YOU Command an Army Group in this Classic Game of Military Chess

TACTICS II… designed to introduce newcomers to the fastest growing hobby today — simulation gaming!

Here, YOUR strategy alone determines the outcome of every game. TACTICS II contains no chance cards, spinners, or random luck elements. Victory or defeat rests squarely on YOUR shoulders. Who knows… YOU might have been a great general if you had been given a chance. NOW! We give you that chance. No military experience necessary! All you need is common sense and a little bit of brains.

The rules reinforce the chess analogy many times, explaining that your units are like “chessmen” and comparing movement to chess movement. The game has, however, more in common with modern wargames than with chess:

Map-based gameplay: Notably, the map is made of squares like a chessboard vs. the hexes that are so common in modern wargames. Units may move diagonally, and moving adjacent to a hostile unit triggers combat. There are various types of terrain — cities, rivers, bridges, mountains, roads, forests, and beaches.

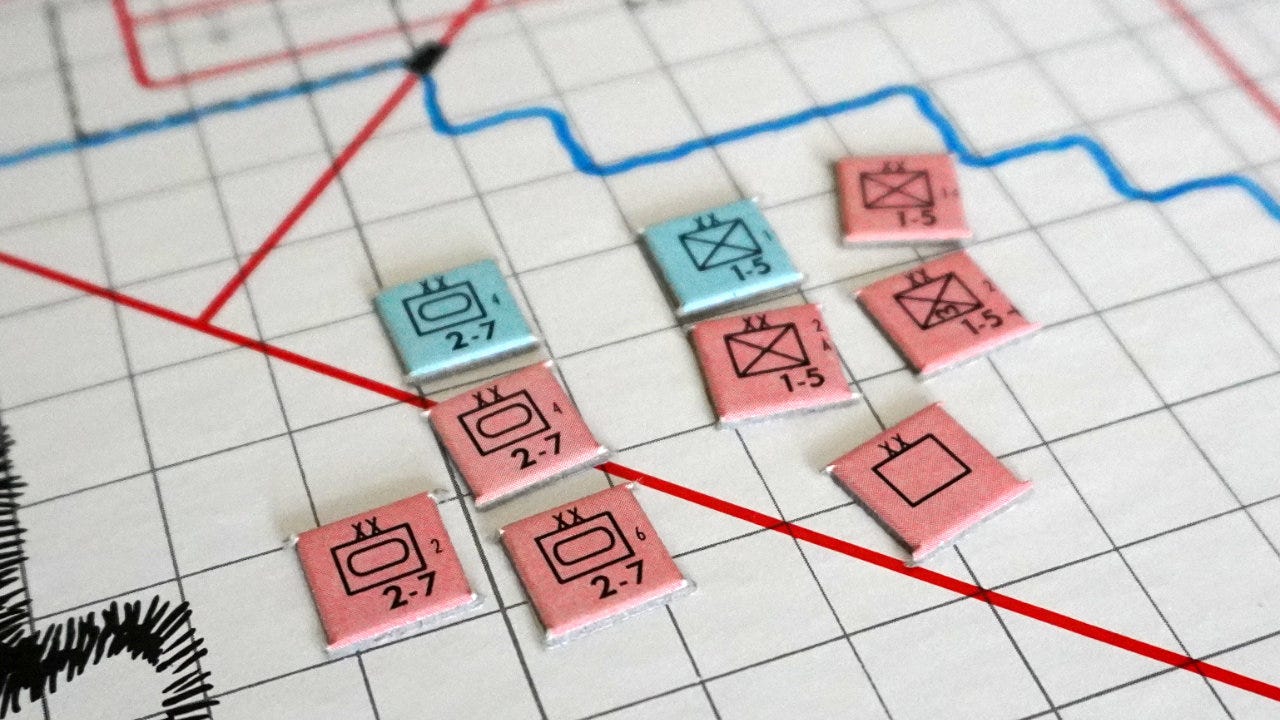

Units or counters: The units are represented on the board by tiny cardboard tokens (chits) in red and blue. Each one has a NATO Joint Military Symbol indicating the type and size, ID number, combat factor, and movement factor. There are six types including Infantry, Armor, HQ, Paratroop, Mountain, and Amphibious.

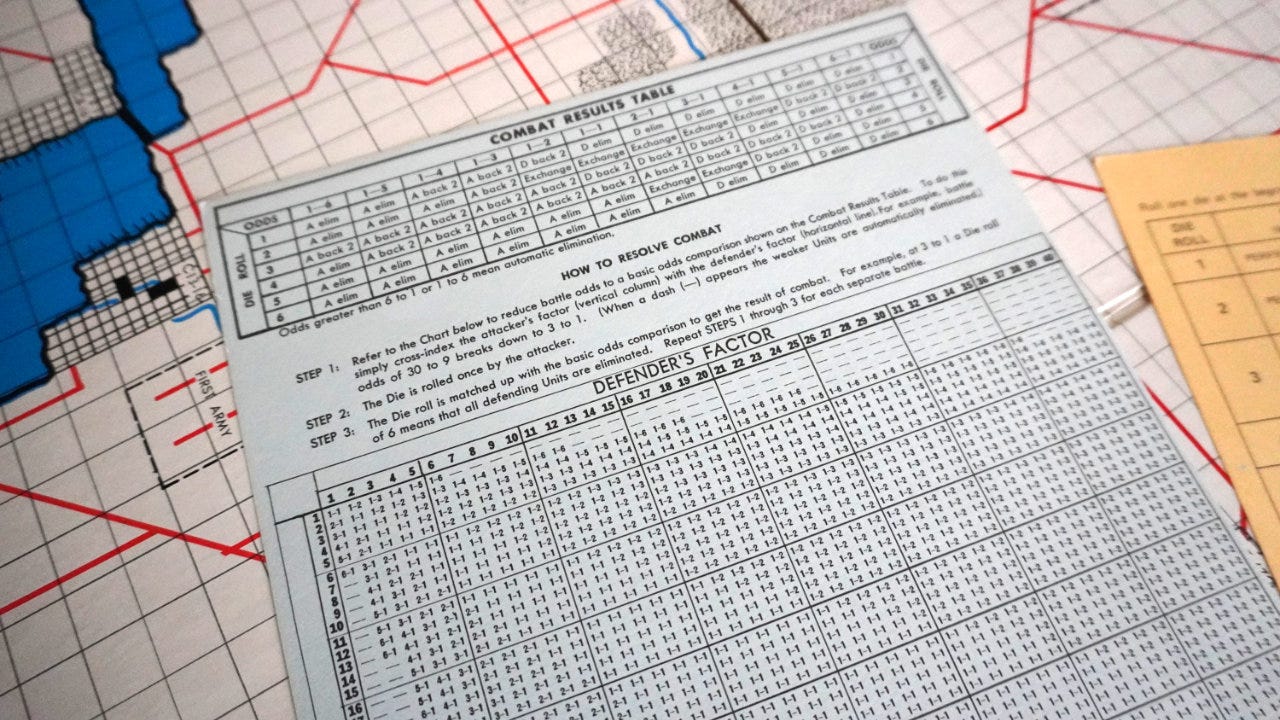

Combat / thematic mechanisms: Contrary to the cover which states there are no “random luck elements,” combat uses a dice roll and combat results table (CRT). After looking up the attacker vs. defender odds (e.g. 3-1 or 2-1), a single die is rolled on the CRT to determine the result (e.g. attacker eliminated, defender eliminated, exchange, etc.). There are also thematic rules for the interaction between unit types and terrain.

Victory conditions: A player wins by one of two conditions: (1) eliminate all enemy units, (2) capture and hold all enemy cities.

Turn-based structure: Simple back-and-forth, alternating turns.

With each side potentially beginning the game with 50 units each, it’s not a short game. Even though the BGG complexity rating is only 2.01, it’s easily a 2+ hour game.

Tactics II publishing and editions

Tactics II was re-published in 1961 and 1973, so the one I first played was probably one of those editions. I was able to pick up a new-in-shrink copy online for about twenty dollars in 2002, which is the one shown in the photos. The Avalon Hill Universal Games & Parts List in the box is marked “Effective November 1, 1995” which is a bit confusing considering the publishing dates were all well before 1995. If any wargamers know the answer, please leave a comment!

Nostalgia and modern expectations

I have wonderful memories of playing Tactics II. For me, it was a new and exciting game and, as a little kid, it was fun to think I was controlling a vast army. Rather than roll and move of Candy Land, there were an almost infinite number of options each turn. I learned basic strategies like concentrating forces, avoiding being flanked, and focusing on objectives. It’s probably not overstating it to say it permanently impacted how I think about tabletop games.

That said, Tactics II probably doesn’t hold up as a modern game. In fact, harsh critiques of the game were already appearing in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The The Comprehensive Guide to Board Wargaming (1977) called it a “respectable but dull abstract introductory game.” The Complete Book of Wargames (1980) dismissed it as, “Aside from its historical importance, this game has no redeeming qualities.”

In some ways, this breaks my heart to see a game I loved dismissed as being more of a relic than a good game. But they are probably right. The game easily ends up as an interminable slog in the middle of the board, with both players having immovable battle lines. It overstays its welcome in play time. The double CRT lookup (first odds, and then result) is fiddly and slower than it should be. The game art is somewhere between bad and non-existent.

I will no doubt play better wargames this year than Tactics II. In fact, I have Command & Colors: Medieval (Borg, 2019) on deck to play soon. It’s another head-to-head two player wargame, but well liked and with positive reviews (currently 8.2 on BGG). It’s even a Top 100 wargame on BGG.

But will it make me feel like I did playing Tactics II for that first time?

Probably not.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Kids don’t need perfect games: It’s easy to fall into the trap of reading reviews, and trying to get the “best” games to play with kids. In reality, it’s the game that taps into their interests and imagination that is best… not what the reviewers on BGG say. The best game is the one that gets played.

Fixing “broken” games: An exercise I enjoy is thinking about how I would improve games that are generally disliked. For example, turning Candy Land into a game with player agency and narrative excitement. Tactics II is another good base to use for this exercise.

Wargames and TTRPGs share common DNA: Even games without combat still share a heritage with wargames. The concept that a game’s mechanisms need to be tied to something in the world of the game is rooted in both. Therefore there is a lot to learn in both directions.

What do you think? Is there value in exploring and trying to learn from old games like Tactics II? Or is it better to learn from modern games that have already incorporated the lessons of the past?

— E.P. 💀

P.S. Watch a solo playthrough of Eleventh Beast at Lone Adventurer!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Negative reviews of well-loved and commonly-played games like 'Tactics II' are typically an expression of 'hard-core-ism', the tendency for opinionated gamers to represent the 'hard-core' element of any gaming community. This is just as true in poker as it is in video-games. Eventually, game-makers confuse the desires of the 'hard-core' community with that of all gamers and the result is products that are increasingly opaque to new gamers. And, over time, the gaming community gradually just becomes that small group of hard-core gamers who die off leaving almost no gaming community behind.

There is value in learning from old games, but probably not from old rules mechanics. They will have something worth improving on, even if it is just that fact that people are interested in playing it for whatever reason. You mention trying to improve Candy Land, and I have done the same thing (Candy Land XTREME is what I called it). The game I keep mentally returning to is Myth, from MegaCon games. It was mechanically broken, but it also had some rules mechanics for handling the enemy forces (it is a coop game) that to this day have produced the most exhilarating rounds of coop play I have ever experienced in the moment. The experience would just always fall apart in the end due to other parts of the rules. But I keep thinking there is a way to improve it somehow, to fix the broken stuff and keep the amazing. Maybe if I win the lottery and can retire early I will actually make the time to get down to brass tacks and really try to fix it.