What does it mean to give players a choice?

Exploring the elements of player agency in tabletop game design

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

This is Part 1 of a two part series on player agency. Don’t miss Part 2!

Last week we looked at even more public domain art resources. This week we are exploring what it means to give players a choice.

What is player agency?

If you’ve been reading Skeleton Code Machine for a while, you know that I often mention “player agency,” but have never really defined it.

Let’s look at a couple different ways of doing that by breaking player agency into its necessary components:

FADC Model

One set of components proposed in Player Agency and Relevance of Decisions (Thue, et al., 2010) includes foreseeability, ability, desirability, and connection:

Foreseeability: Can the player reasonably predict or anticipate the outcome of their choice?

Ability: Does the player have the ability to make the outcome happen?

Desirability: Does the player actually want the outcome to occur?

Connection: Was the resulting outcome connected to the predicted outcome based on either previous experience or future prediction?

I can appreciate this model, particularly because of the focus on the actual outcome matching the player’s anticipated outcome. Making a choice and then getting something completely unexpected is hardly a choice at all.

CCI Model

A simpler model is proposed by The Power of Choice: Player Agency in Tabletop Role-playing Games (Amauger, 2023), with just three key elements:

Choice: Multiple options are presented to the player. This could be in the form of a list of possible board game actions, or the wide open world of creative problem solving in TTRPGs.

Control: The player has the ability to act upon the options. If a game presents a list of actions and/or choices but the player is, in practice, limited to just one of those possibilities, it’s not actually a choice. The player must have the power to make a selection based on their desire.

Influence: The player’s decisions changes the world of the game. Having choices presented and selecting one of them doesn’t mean much if it doesn’t impact the game.

While this model is less comprehensive than the FADC model above, I appreciate its simplicity. We can easily look at a tabletop game, and ask if it gives the player choice, control, and influence. This is a quick and easy diagnostic tool when trying to increase player agency in a game design.

Let’s try it

I’ve been teaching a free tabletop game design class at a public library over the last few weeks. Last week’s class was focused on player agency and meaningful decisions.

To help illustrate it, I used a version of an exercise from the Gwinnett County Public Library:

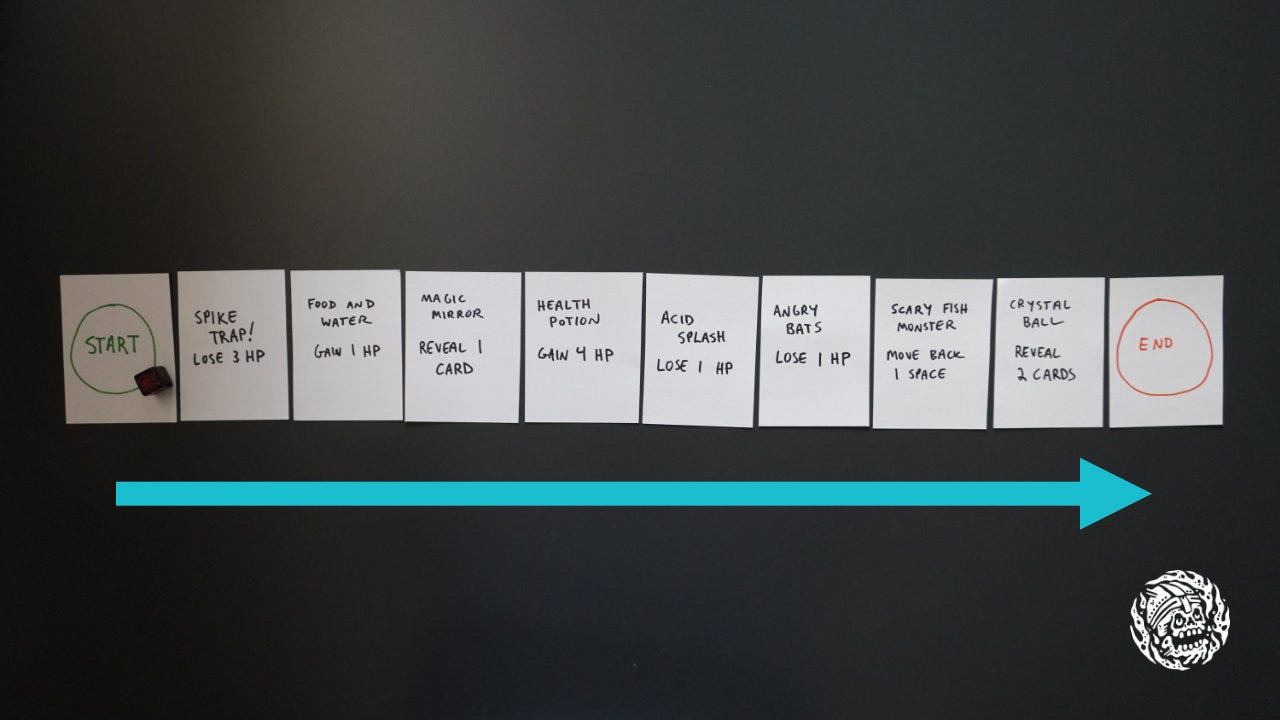

Objective: Get from Start to End

Choose a random theme using the d6+d12 theme generator.

Take ten (10) blank cards or pieces of paper:

Write START and END on two of them.

Write simple events on the other eight (8) cards such as losing/gaining HP, revealing other cards, or going back one space.

Add a bit of theme to each card (e.g. Acid Splash! for losing HP).

Place a spare die or token on START as your player.

You begin with 5 Hit Points (HP).

After creating our cards, we ran through a few setups to demonstrate iterative design.

Setup 1: Zero player agency

In the first setup, we put the Start and End cards at the two ends, with face up cards randomly distributed in between. The player advances one card each turn, reveals the card, and resolves the action on it.

There are no choices presented to the player, and all the information on the cards is already revealed at the start of the game. At least one of the cards (i.e. move back) completely breaks the game.

We all agreed this might be the worst game ever invented.

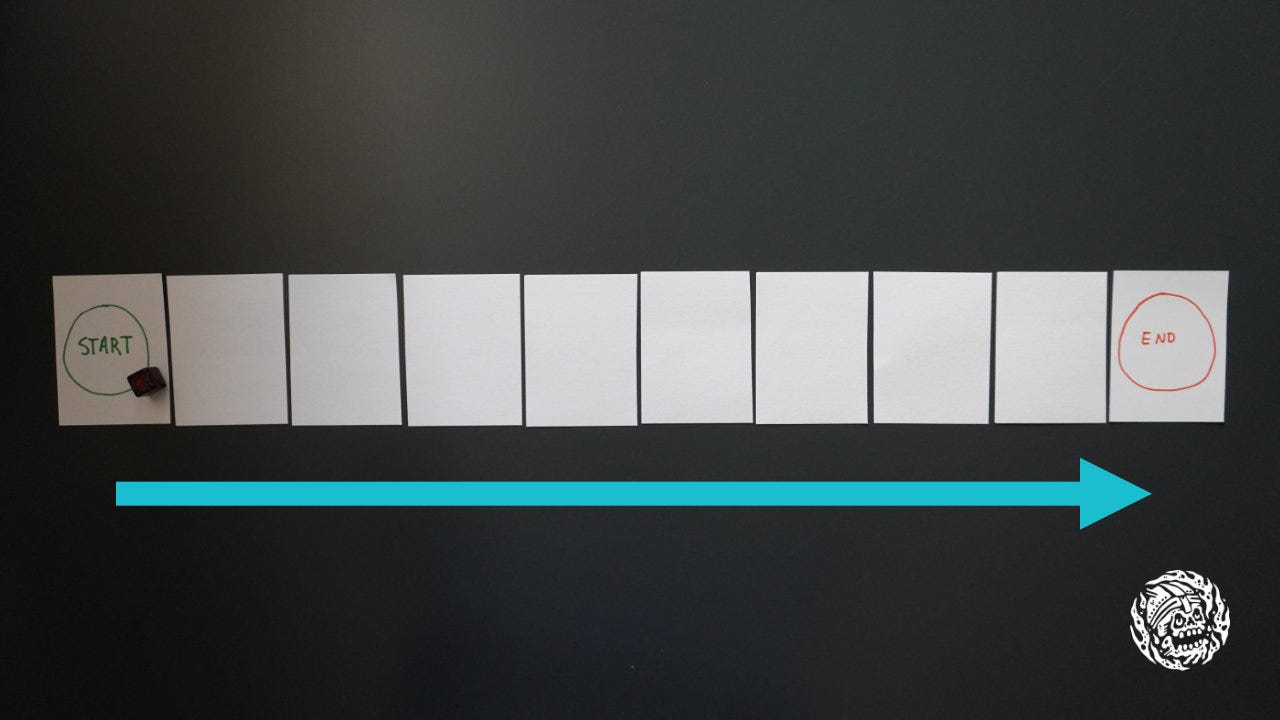

Setup 2: Adding hidden information

Let’s make some iterative design changes. This time, almost the same setup but the cards and randomly placed face down between Start and End.

This is effectively Candy Land (Abbott, 1949) but worse. You still don’t have any choice. The only change is that you don’t know what the next card will be until you reveal it.

Hidden information and chance can add some excitement, but it’s usually not enough to carry the game. Still a pretty awful game.

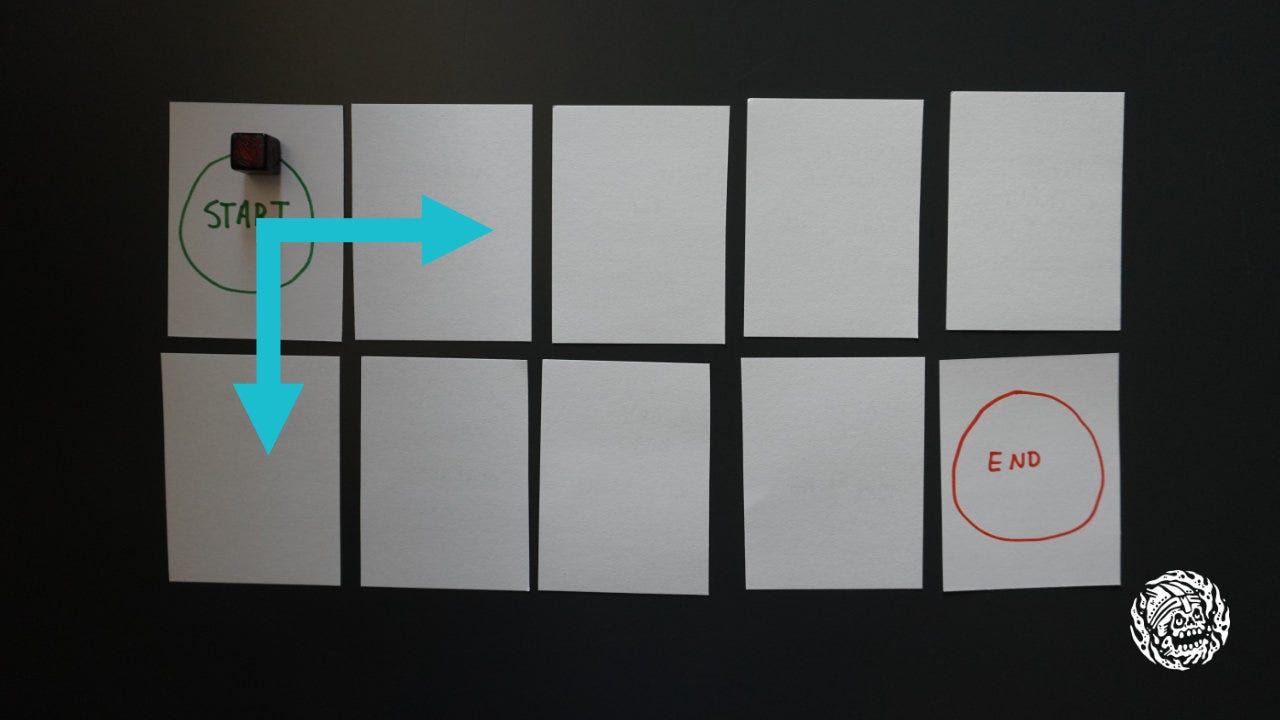

Setup 3: Adding some decisions

This time we rearrange the cards into a 5x2 grid of randomly distributed, face down cards. Each turn the player can move to any adjacent card, revealing it, and resolving the action. Finally we have some player choice!

But does this actually add player agency? Using the CCI model, it does present the player with choices, and it does give the player the control to make the choice. The choice does not, however, really influence the overall world of the game. The influence exerted on the game is minimal at best.

And yet, this is already a far better game than the first setup! Even the slightest addition of something approximating player agency can improve a game.

Improving our game

Although the game is improved by adding player choice, I doubt anyone would call it fun.

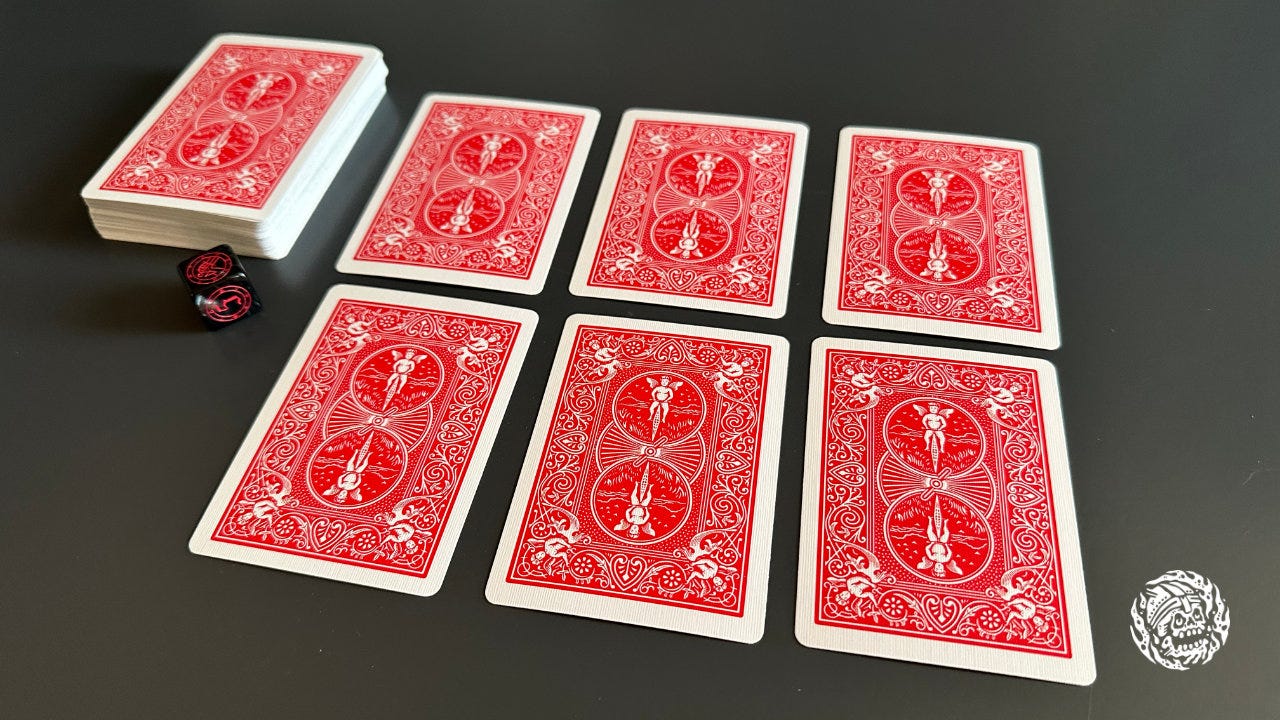

The class assignment for the following week was to continue to improve the game: add more components, use a 52-card poker deck, increase player agency, consider input-output randomness, enhance the theme.

I ended the class exercise with the example of Mini Rogue (Stefano & Gendron, 2020) to show what the game might become:

Mini Rogue is a minimalist dungeon crawler board game in which one or two players delve into a deep dungeon in order to get a mysterious ruby called the Og's Blood.

The players must choose how to spend their resources to be powerful enough to confront ever more difficult monsters and hazards. Randomly generated levels and encounters make every playthrough a unique experience!

With a simple grid of nine cards and a player token, this game is a fun take on the rogue-like genre. Hopefully the connections to our little prototype are apparent!

Cards in a grid

You might also notice that a few iterations later, you might end up with something resembling the Carta SRD by Peach Garden Games:

The base idea is that players lay cards out in a grid , and then turn them over one at a time, exploring prompts and mechanics as they do. The game is a sort of boardgame / storygame hybrid, where players explore journaling prompts by physically moving their marker from card to card and looking up the results.

Next week we will dig into the Carta SRD and see how games based on that system can use player agency and countdowns create engaging player experiences!

False choices

It’s worth noting that it’s easy to add what I would call “false choices” into a tabletop game design.

This is when the player must choose between multiple options, but:

The player has no information or knowledge by which to make the decision. All options seems equally good or bad, and a random selection is as good as any.

The choices all lead to the same outcome, regardless of the option selected.

The output randomness built into the system greatly outweighs the impact of any actual player decisions based on available options.

Mark Bigney at So Very Wrong About Games sometimes refers to the last point as “roll a six, win a cookie.” Meaning you might as well roll a six-sided die and see if you won because the outcome is ultimately random.

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

All models are wrong: As we discussed with player types, all models are wrong but some models are useful. Neither the FADC or CCI models are perfect, and much is missing. Yet they both give us a shared vocabulary and a way to talk to about player agency.

Increasing player agency: When designing a game, consider how you can increase the elements of player agency: choice + control + influence. Be careful to balance all three elements and beware false choices. Adding more choices without adequate impact and influence on the game world might make it worse.

Iterative game design works: In just three steps we went from what might be the worst game ever designed to something significantly less bad. Imagine ten, twenty, or a hundred iterations later! It’s hard to beat making some cards and trying out a design to get ideas on how to make it better.

There are countless models for thinking about player agency, and we looked at two of them (FADC and CCI) in this article. Which of those two do you think is the most useful when designing a game?

See you next week when we continue with the Carta SRD!

— E.P. 💀

P.S. If you want to know more about the tabletop game design class I’ve been running for a public library, sign up for the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

CCI is pretty close to Chris McDowall’s [BASTIONLAND: The ICI Doctrine: Information, Choice, Impact](https://www.bastionland.com/2018/09/the-ici-doctrine-information-choice.html?m=1).