The Elemental Tetrad

Exploring the four elements in (almost) every game you play

Welcome to Skeleton Code Machine, a weekly publication that explores tabletop game mechanisms. Spark your creativity as a game designer or enthusiast, and think differently about how games work. Check out Dungeon Dice and 8 Kinds of Fun to get started!

Last week we looked at layers of theme in tabletop games using a model proposed by Sarah Shipp in Thematic Integration in Board Game Design.

This week we are using a different model or “lens” to analyze games: The Elemental Tetrad.

The Elemental Tetrad

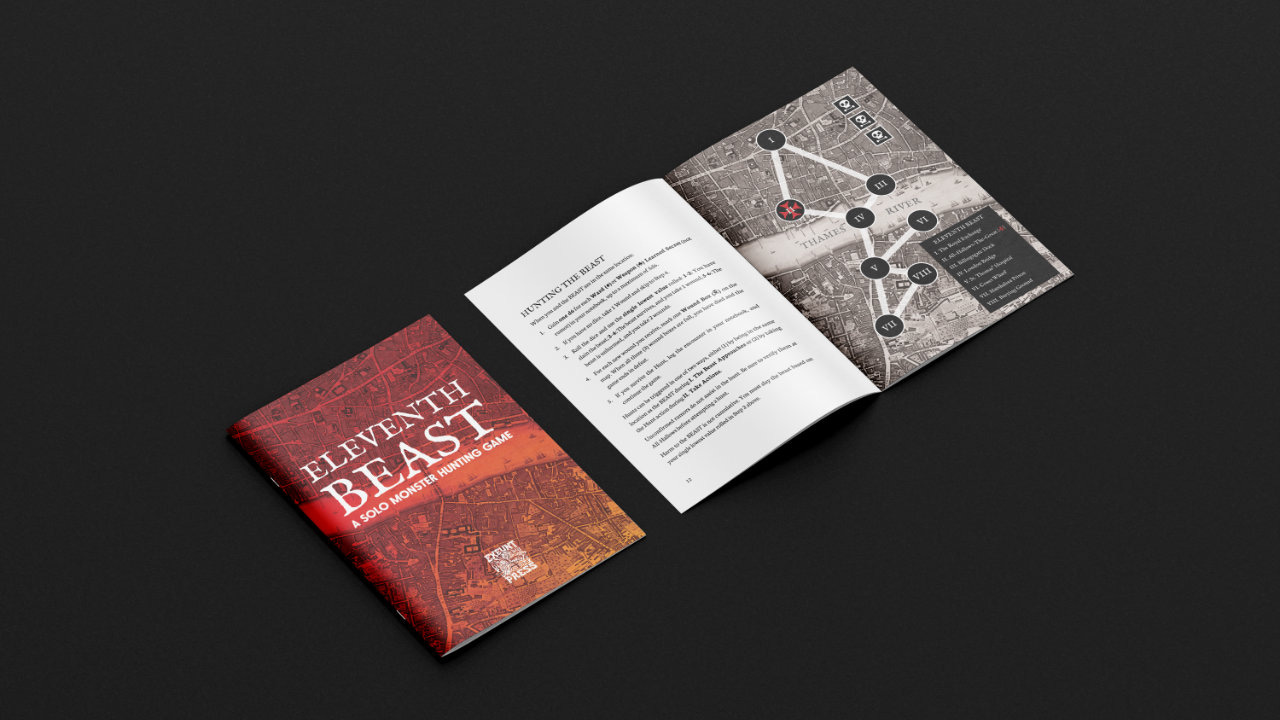

Think of the different games you’ve played. Consider all of the countless games available, such as the TTRPGs in the photo above.

What do they all have in common?

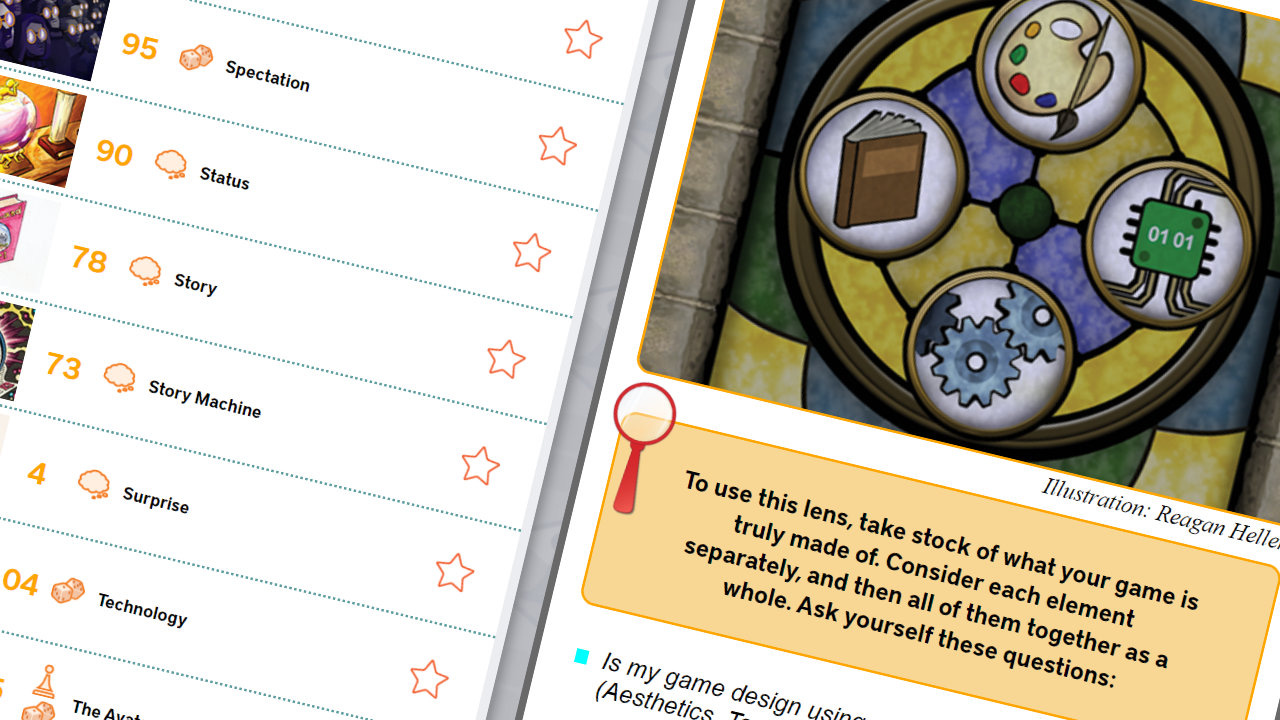

The Elemental Tetrad is one of the “lenses” proposed by Jesse Schell in his book The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses. It’s a simple, four part way of looking at almost any game. It works for tabletop board games and roleplaying games just as well as it works for video games:

1. Mechanics

Mechanics are the core rules and procedures of the game. They define what players can do, how they interact with the world of the game, and how the game responds to their actions.

A simple example would be the rules which define how each piece in a chess game may move. A more complicated example would be the many mechanisms in a game like Fire in the Lake: Second Edition (Herman & Ruhnke, 2018): area majority, dice rolling, variable phase order, and variable player powers.

2. Story

Story is the narrative built using plot, characters, and other facets of the game’s world. The story and aesthetics are key components of a game’s theme. While the mechanics tell us how to play a game, the game’s theme tells us why we are playing the game.

Using Fire in the Lake as an example, the theme involves the Vietnam War, modern warfare, counter-insurgency, and political motivations.

Notably, this is the one element that might not apply to all games. What is the “story” for a purely abstract game like Tic-Tac-Toe or Go? I don’t have a good answer for that one. Please share your thoughts in the comments!

3. Aesthetics

Aesthetics are the visual, tactile, and other sensory elements of the game. This includes illustrations, physical design, placement of components, and how the components are handled and used in the game.

Note that this isn’t always limited to just visual aesthetics. Party games and negotiation games develop an auditory aesthetic as they are played. Other games such as Dwellings of Eldervale (Laurie, 2020) include minis that roar like monsters.

4. Technology

Technology is the medium of the game, including the components or platform that enables the game to be played. For tabletop games this might be analog components made of paper and plastic, while for video games it includes the software, SDK, and more.

The technology for most TTRPGs can be minimal: dice, paper, and pencils. Some TTRPGs do, however, have companion apps that can supplement and assist gameplay. Mothership RPG is a good example of a TTRPG that has a rather nice mobile app.

You might also consider digital platforms like Tabletop Simulator or BGA when thinking about the technology of a game.

Looking at Eleventh Beast through the lens

It’s helpful to use an integrated example with all four elements. Here is how we might analyze Eleventh Beast, a solo monster hunting game:

Mechanics: Core game loop that involves rolling dice to place new rumors, selecting two actions from a list, and potentially moving the Beast. Resolving combat (“The Hunt”) if triggered.

Story: You are a monster hunter in 18th century London. A Beast arrives every thirteen years, and the next one is coming. Move around the city to collect rumors and convert them into wards and weapons to use during the final hunt for the Beast.

Aesthetics: A historically appropriate 1746 London map. Bold black and red colors. Uses 15th and 16th century public domain art including Lo Stregozzo by Agostino Veneziano and Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons by Martin Schongauer.

Technology: Minimal technology. Dice (d6 and d8), paper map, some tokens, and items for journaling.

It’s easy to see the connections between the story and aesthetics. The trickier one to get right is having the mechanisms/technology blend with and support the story/aesthetics.

In Eleventh Beast one way I attempted to do that was to flip the idea of solo TTRPG combat. Instead of frequent combat where “I hit you. You hit me. Repeat.” the game is almost entirely prep for a single combat. The hunt usually will only happen once, and will be lethal (for either the Hunter or the Beast). This supports the story that the Beast is deadly and to be feared.

Balancing the elements of the tetrad

In Game Design: A Deck of Lenses the Lens of The Elemental Tetrad card suggests the three following questions:

Is my game design using elements of all four types (aesthetics, technology, mechanics, and story)?

Could my design be improved by enhancing elements in one or more of the categories?

Area the four elements in harmony, reinforcing each other, and working together toward a common theme?

These questions are a good place to start when analyzing a game. The challenge is to take the four elements and make them work together, especially when they influence each other.

The result of all four elements is the player experience, which should ultimately be the goal of any game design.

Learn more

The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses by Jesse Schell

Game Design Fundamentals for HRI Researchers by John Muñoz

The Elemental Tetrad of Games at the Cleveland Institute of Art

Interview with Jesse Schell by The Corner of Story and Game

Conclusion

Some things to think about:

Many models are available: We’ve explored MDA, CCI, Bartle’s Taxonomy, and the Three Layers of Theme. Each one is a different way of approaching a game, and provides a different view. Explore them all and use the ones that feel right for your game designs.

Just one of many lenses: The Elemental Tetrad is just one of over a hundred lenses listed in the Art of Game Design Deck. Other lenses include The Lens of Fun, The Lens of Curiosity, and The Lens of Resonance.

Practice breaking games into their components: I’ve found it helpful to think about the games I play using some of these models. The other night while playing Terraforming Mars (Fryxelius, 2016) on BGA we noted that the flavor text was missing from the cards, removing a Layer 3 Opt-in thematic element. How does that impact the experience of the game?

What do you think of the Lens of the Elemental Tetrad? Is it a useful model for game design? Try breaking one of your games into the four elements and post the results in the comments!

— E.P. 💀

P.S. If you enjoyed Dice Week, you should check out Three Knife Ash. It’s a collection of three dice games that you can use in Pirate Borg, MÖRK BORG, or really any TTRPG. Let your players gamble and win prizes!

Skeleton Code Machine is a production of Exeunt Press. All previous posts are in the Archive on the web. If you want to see what else is happening at Exeunt Press, check out the Exeunt Omnes newsletter.

IMO the story of Tic-Tac-Toe is a meta-story about player interaction. “Greg began in the top middle square. Tina was surprised by the choice and took the middle space. Greg soon regretted his decision when Tina got the easy diagonal.”

As a narrative designer, I’m often designing not just the fiction that contextualizes a game world, but also elements of the player’s overall experience. For example, in a game about the horrors of war, designing a sequence where the player walks through a quiet battlefield. It doesn’t necessarily answer “why,” but it suggests to the player how to feel about the mechanics.

Some of my favorite games don’t have stories. I’m thinking of simulation games like SimCity or worldbuilding paper and pen games like cartographer. But there is an expectation that players will create a story in their head or on paper, of the worlds they are creating and controlling.